Important Shanghai issued passport

1947 Polish consular issue from the Far East.

The document in the article here was issued in China, at a period of unrest, shortly after the hostilities of World War Two have ended.

The document holder and some of the signed endorsements inside make this exotic travel document here an important collectible and historically significant as well.

But before we continue on the item itself, I would like to start off with some information on the location it was issued at, the Chinese port city of Shanghai & its amazing story of the Jewish community that was living in Shanghai during World War Two and under the Japanese occupation.

The Chinese city of Shanghai is located on the coast, on the eastern section of the country. It has been an attraction for foreigners, merchants and civilians, for many years, with the 1842 Opium War leading to a full blown expansion of the foreign concessions foreign concessions growing rapidly to the north and western sections of the city, that permitted only foreigners to take residence there (the Shanghai International Settlement was known in Chinese as 上海公共租界; and this came about following the signature of the Treaty of Nanking). Eventually, the 19th century saw every major foreign power in the Far East trying to control sections of the city that housed its nationals, and slowly becoming a ‘country within a country’. By the 1920’s, the city was controlled by several foreign “local” municipal governments comprising of nationals from several European countries: the English, French and German enclaves for example.

This situation was not limited to Shanghai alone, and up to 1949 several other major Chinese cities where “jointly” run by both local Chinese authorities and foreigners as well, such cities included Guangzhou (Canton), Hankow, Tianjin, Beijing and Harbin. This could also explain why various “official” municipality issued invoices and receipts would be found in French, German, Russian or other language as well.

Trying to control the city with so many local and foreign influences was hard enough, and by the early 1930’s violence and conflict was also thrown into the picture.

The Japanese aggressive behavior towards its neighbor in the west was getting more violent and territorial claims were already being “implemented on the ground”: The Japanese invasion of north-eastern China culminated with the establishing of the Manchurian Imperial State around 1932 and at the same time we can find the first Japanese offensive against the city of Shanghai known also as January 28 Incident.

The second attempt by Japan on the city came in 1937 during the Second Sino-Japanese War and was one of the major battles of that war known also as Battle of Shanghai: After a period of 3 months fighting, large portions of the city fell to the Japanese, leaving the international settlement “free” and out of their reach. As hostilities continued and fear among the foreign powers grew, foreign armies present on the mainland began to withdraw, for example, the British withdrew its garrisons from Shanghai on August of 1940 (added image of an emergency script that was issued locally for use by the garrison troops around 1939, the period when Siege Currency was being produced due to the lack of funds entering the sieged city). A year later, after the Pearl Harbor attack, the Japanese made a complete invasion and occupation of the city including the International Settlement. By the end of 1941, Shanghai was under full occupation.

But before all this was taking place, Shanghai was also an important safe haven for foreigners and mainly Jews, who were trying to escape hostilities back in their home in Europe.

The rise of Adolf Hitler and the NSDAP party to power in 1933 was a major turning point for the Jews living in the Continent, starting with Germany and then spreading to other communities and countries as well. With the violent actions that were being perpetrated upon the Jewish population growing day by day, coming in the form of anti-Jewish legislation (starting already in 1933) and anti-Semitic physical attacks, reaching the pinnacle with the Kristallnacht atrocities in 1938, the Jews saw that the only way to escape and survive was to leave Germany and to leave Europe as well. Those who were lucky and strong enough found refuge far away in the Far East, setting sail to find a safe haven in the Chinese coastal city of Shanghai.

The city was one of the few places, if not the only one, that did not require entry visas. The Chinese authorities, the Shanghai Municipal Council (SMC) for example, did not prevent anyone from entering the city if he or she did not carry a Chinese visa, thus applying for one at the end was not necessary (still, in most cases, one needed a final destination visa inside the passport if one wanted to obtain transit visas as well, thus if one obtained the US visa, for example, other needed transit visas could be applied for with relative “ease”: Japanese, Soviet, Lithuania or Latvian, Italian etc). Some passports by having the Chinese visa applied inside would include also special temporary transit visas being issued by the British or Italian consulates, for example.

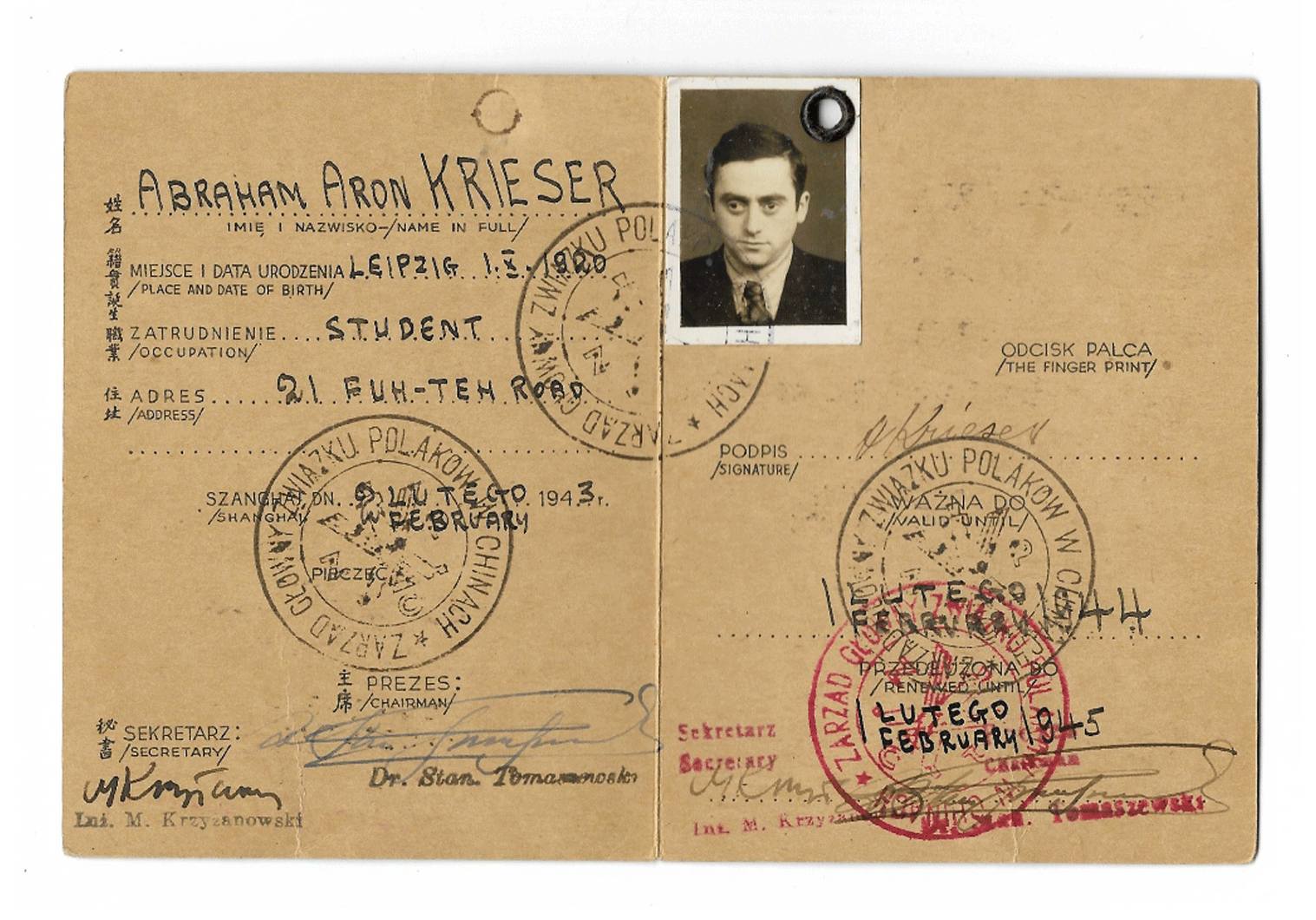

Thus, from the period of 1938 to around 1941, Shanghai gave refuge to around 30,000 Jews who fled Europe, with a large section of them arriving from Germany, Austria and Poland and the period of 1943 to 1945, the time of the formation of the Shanghai Ghetto (added some images of documents issued or used by the Jewish inhabitants living inside the ghetto during the war).

The passport:

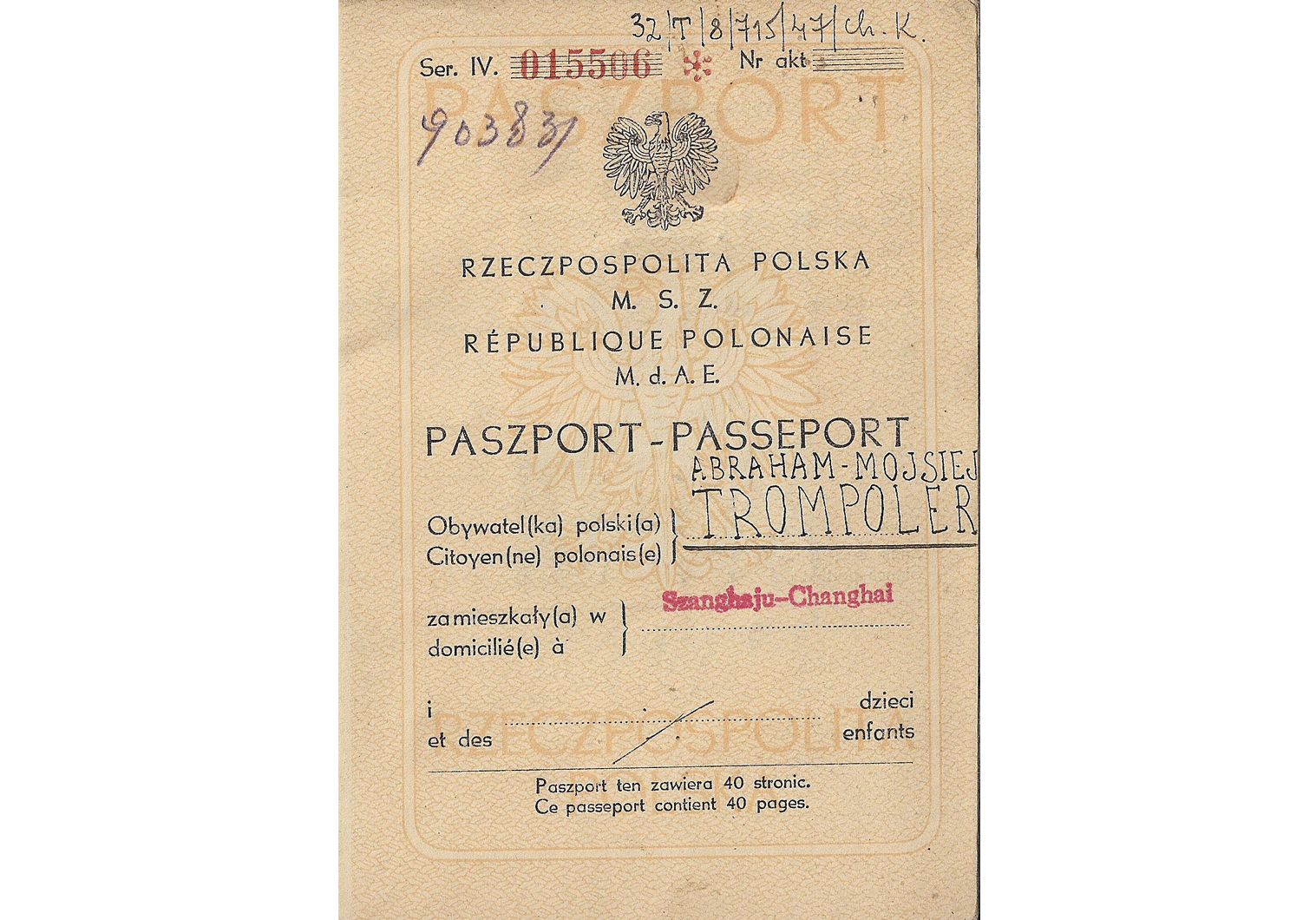

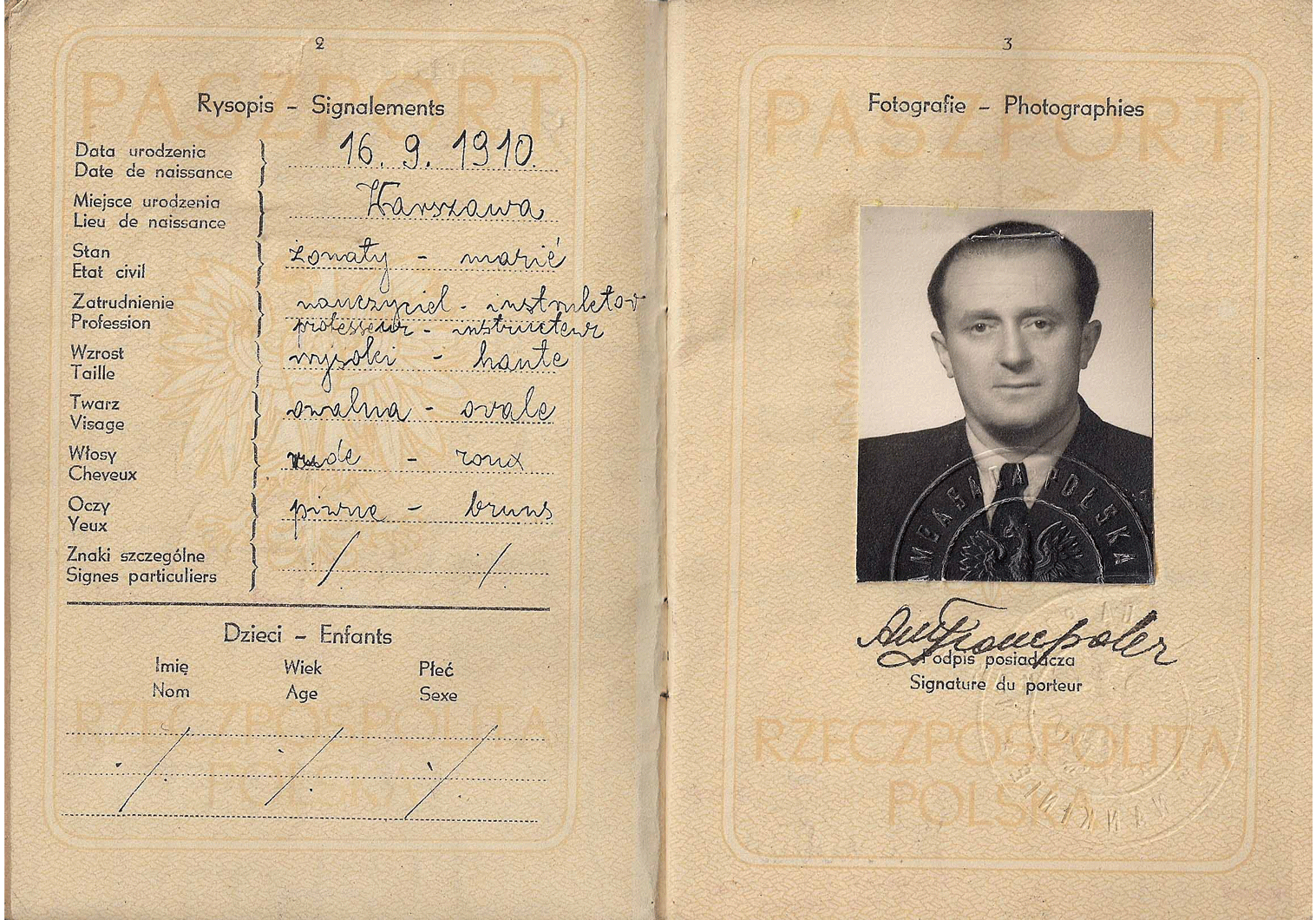

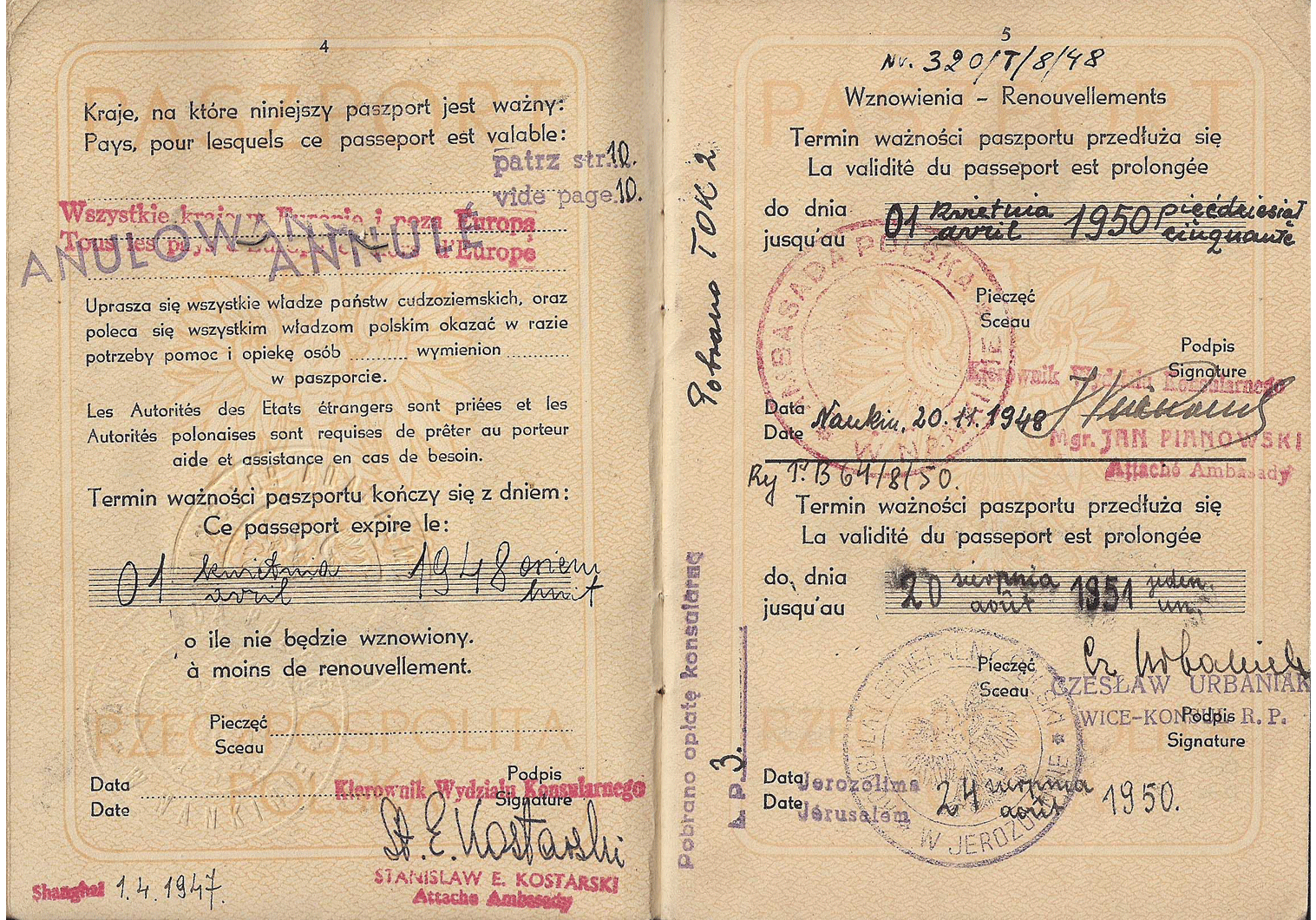

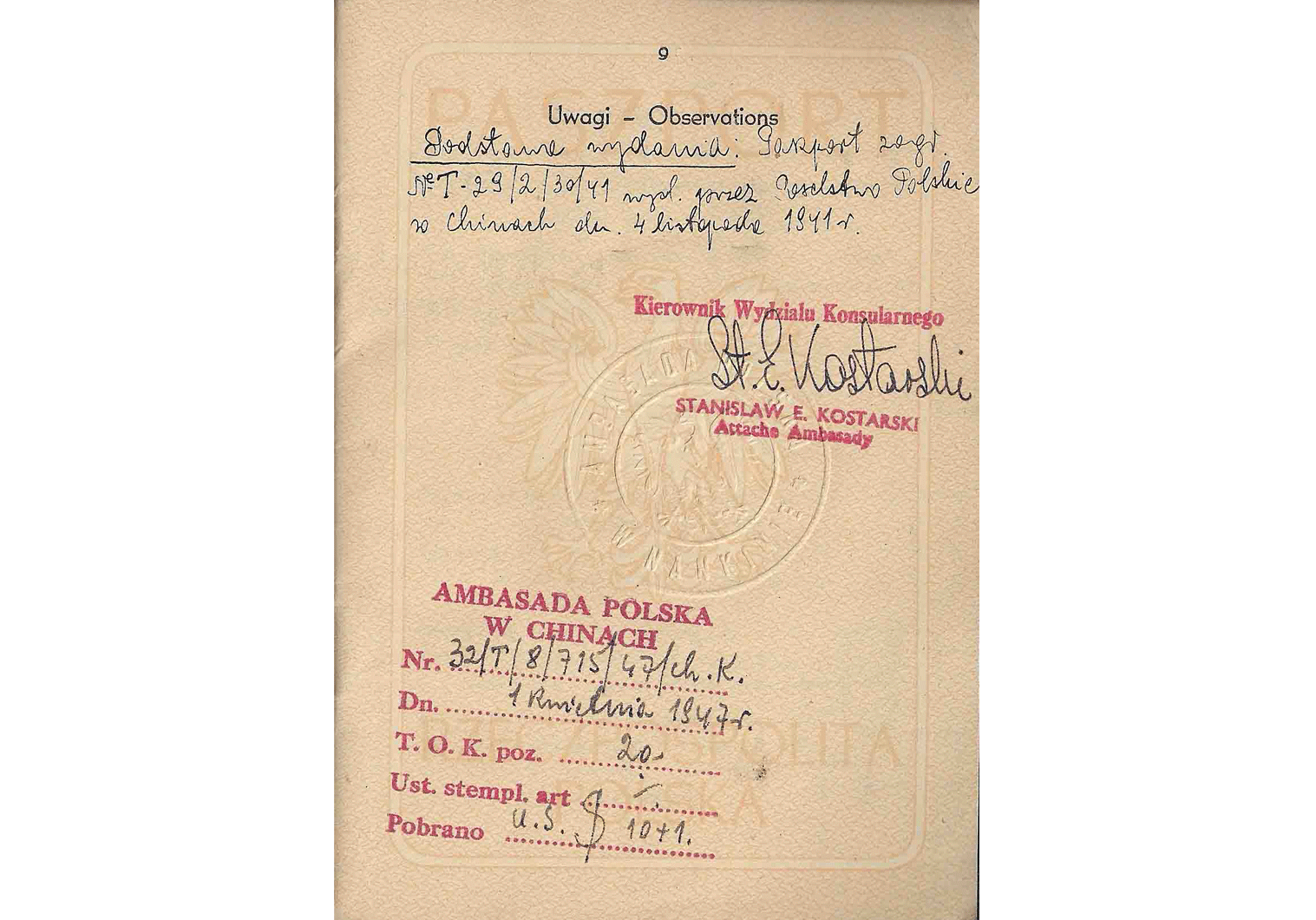

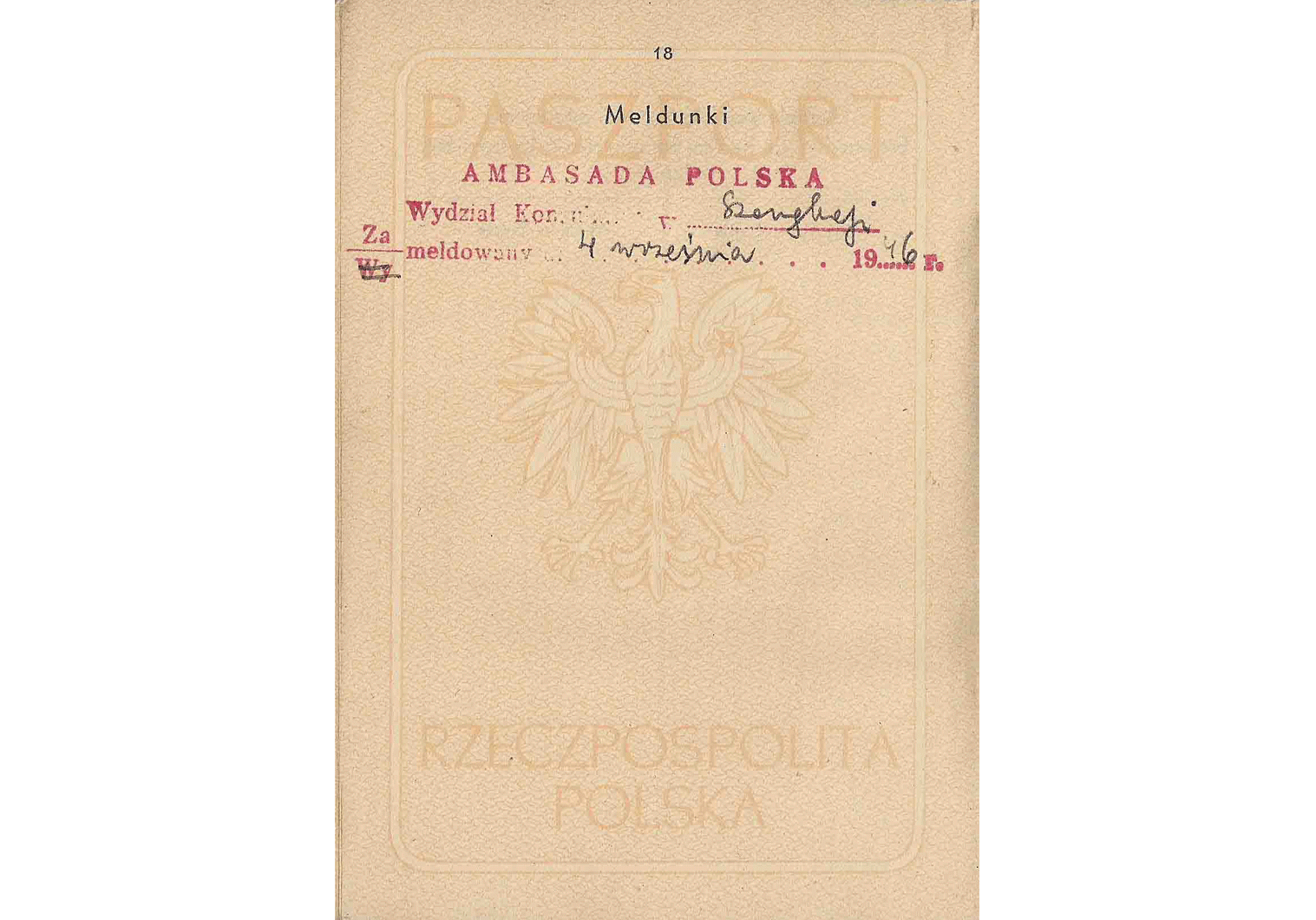

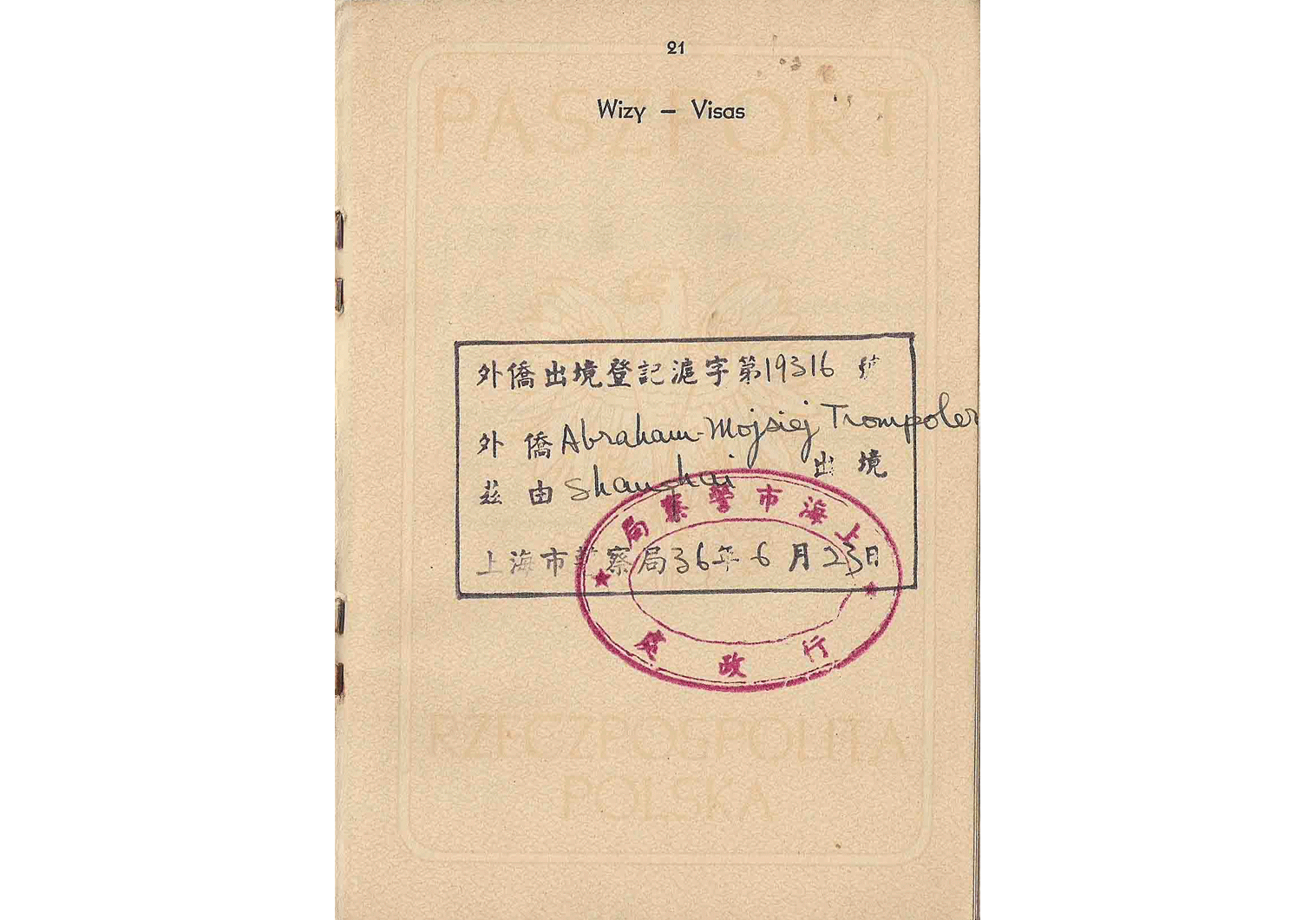

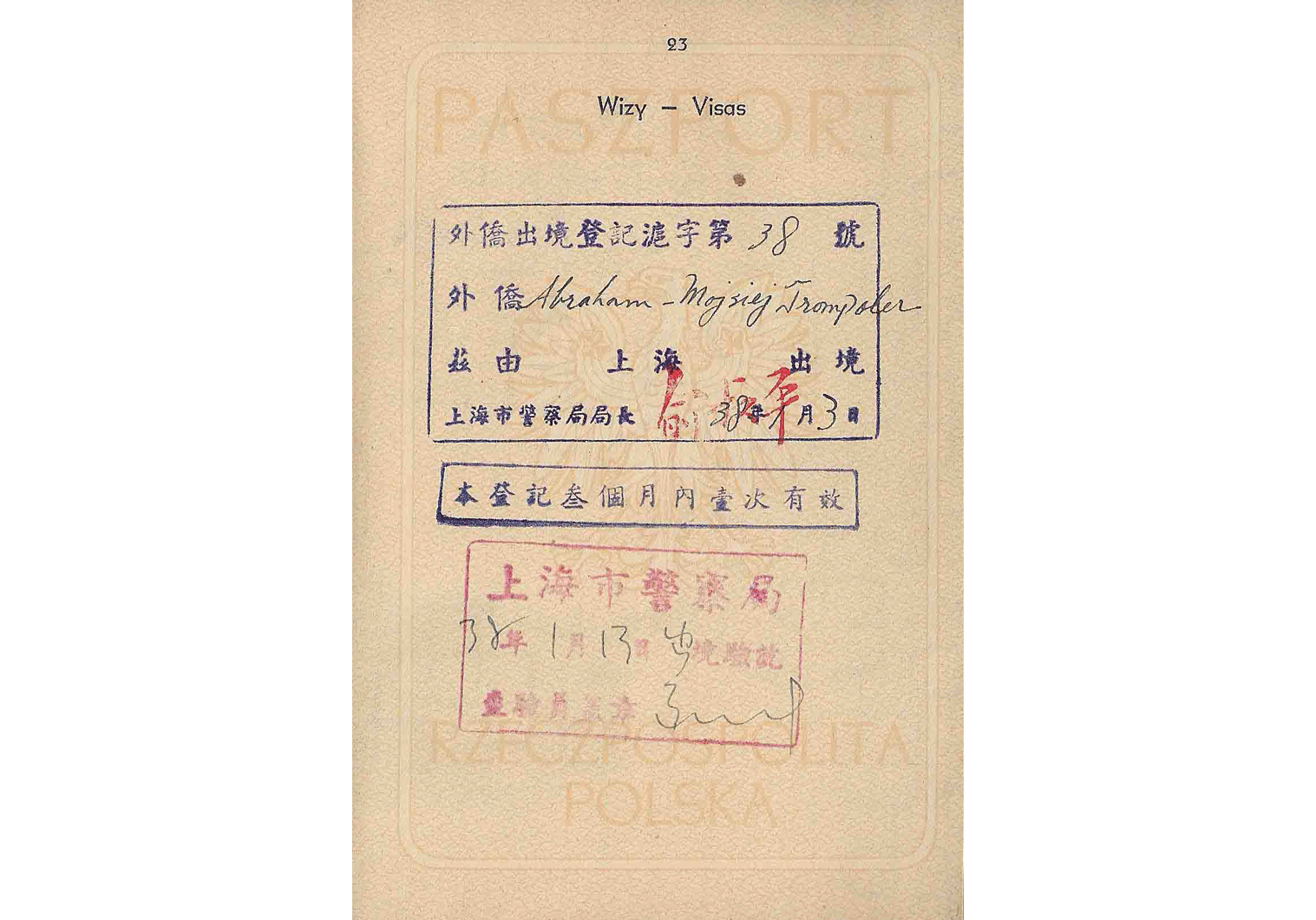

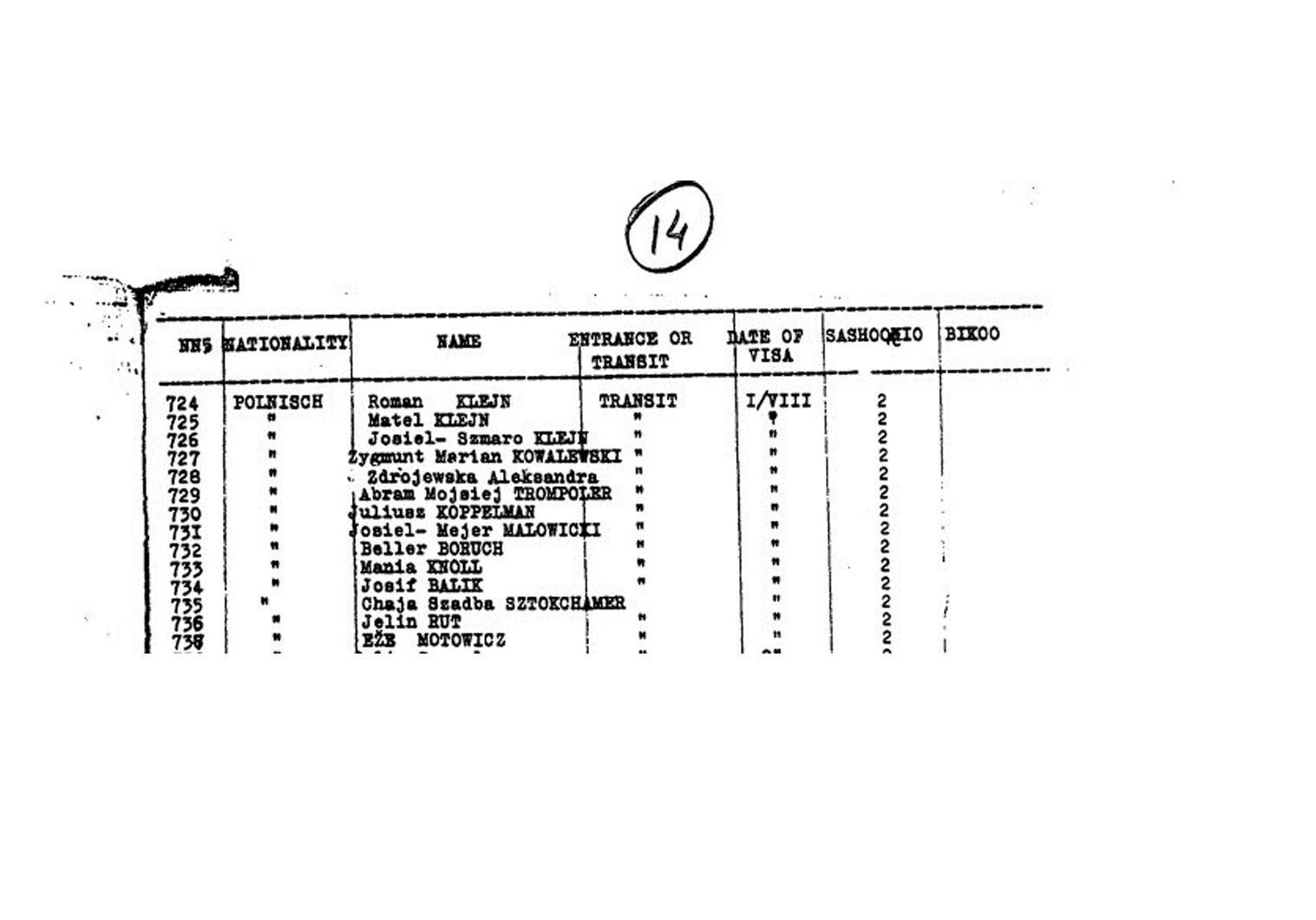

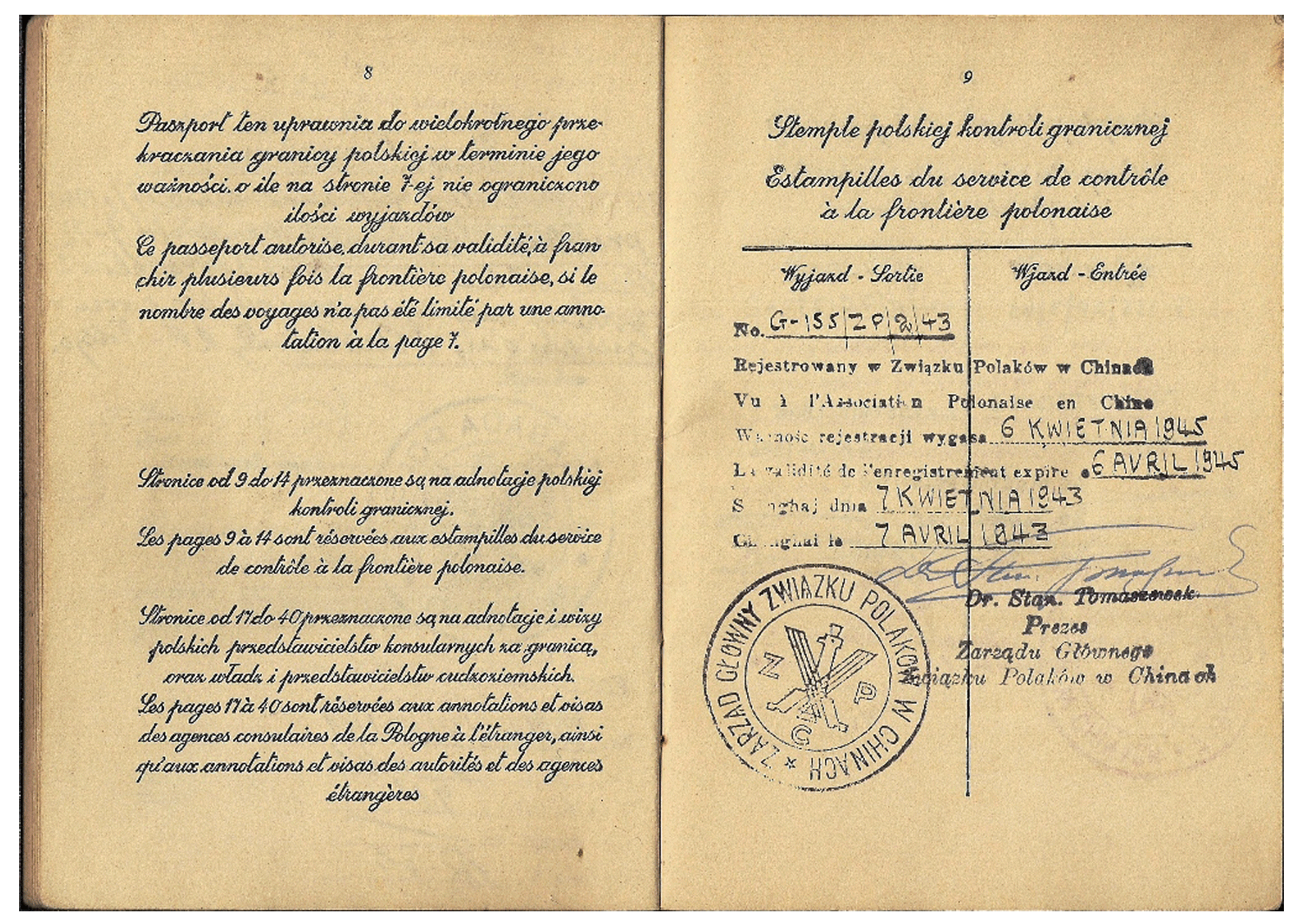

Polish passport number 32/T8/715/47/ch/K. was issued in Shanghai April 1st 1947 to 36 year old Abraham -Mojsiej Trompoler, a Jewish community activist (teacher & instructor) in the city during and after the war and also in Israel once reaching the country later on. Some research has also shed light on the way he reached China, and it was done via a Sugihara issued visa (#729) from Lithuania in 1940. There are records kept in the Polish Foreign Ministry as well that indicate he registered at the Polish consulate in Shanghai in 1941, and the records show that his profession was most likely that of an electrician. His address inside the ghetto was at 54/17 Chusan Road. On April 11th he was given the passport here (also mentioned on page 9 of the passport here).

The passport was issued by Polish diplomat Stanisław E.Kostarski who was an attaché in the Embassy. Here are some brief points to this individual: He was born in 1920 and was a member of the Home Army (Armia Krajowa, AK), which was the most significant and important, during WW2, resistance movement, loyal to the Polish government-in-exile. The individual here became Poland’s representative to China in a period where others alike serving in the AK were persecuted, and this is rather odd, further research is needed. After the war he was a reporter for the Polish daily “Życie Warszawy”. He was appointed Chargé d’affaires before the formation of the The Peoples Republic of China (PRC).

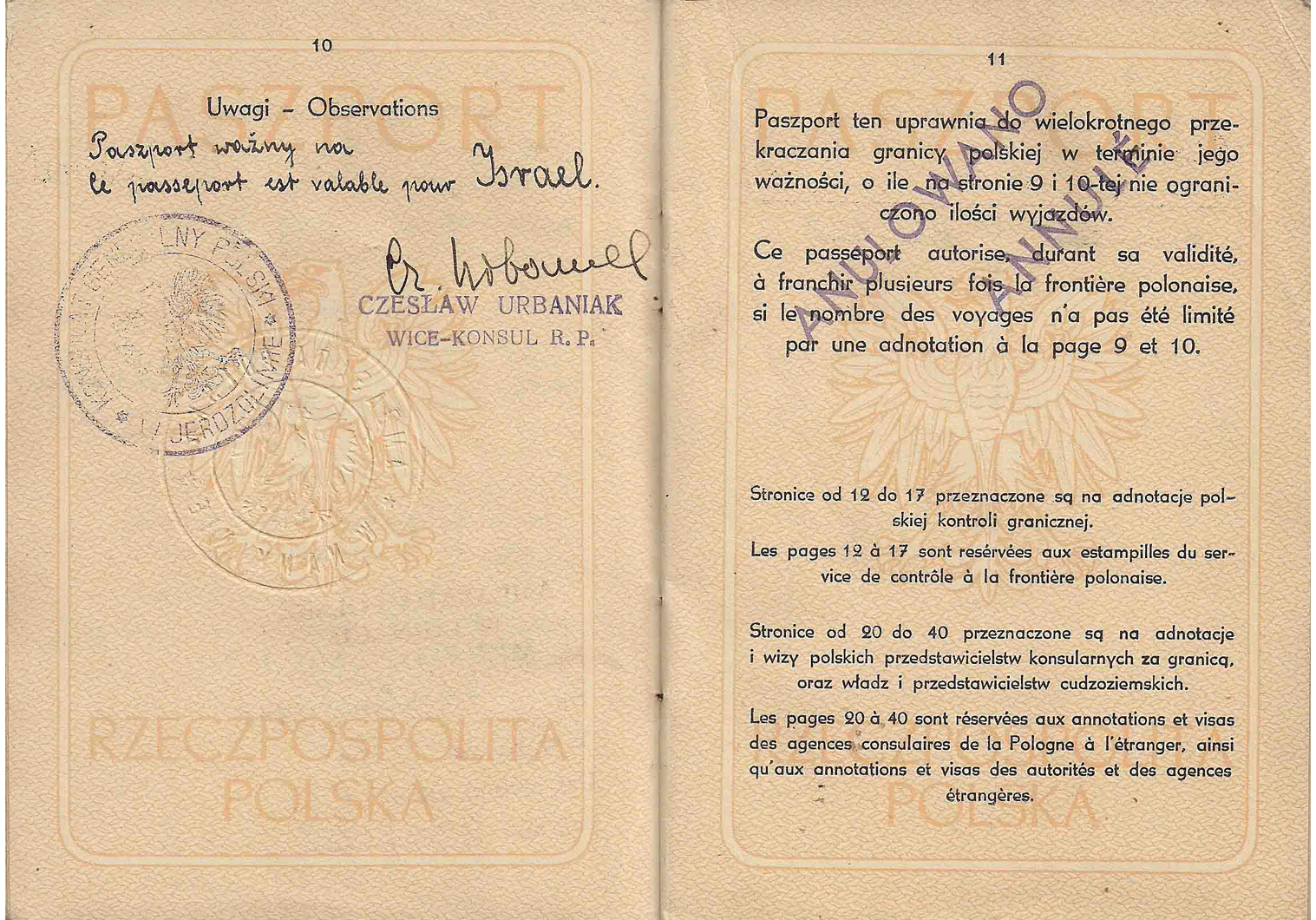

Another important signature inside the passport was of Mgr. Jan Pianowski, from November 28th 1948, who was Poland’s first representative to P.R.China, Chargé d’affaires in Nanjing from October 27th 1949 (several months later Poland’s first ambassador to the PRC was Juliusz Burgin who was appointed by the republic’s president Bolesław Bierut).

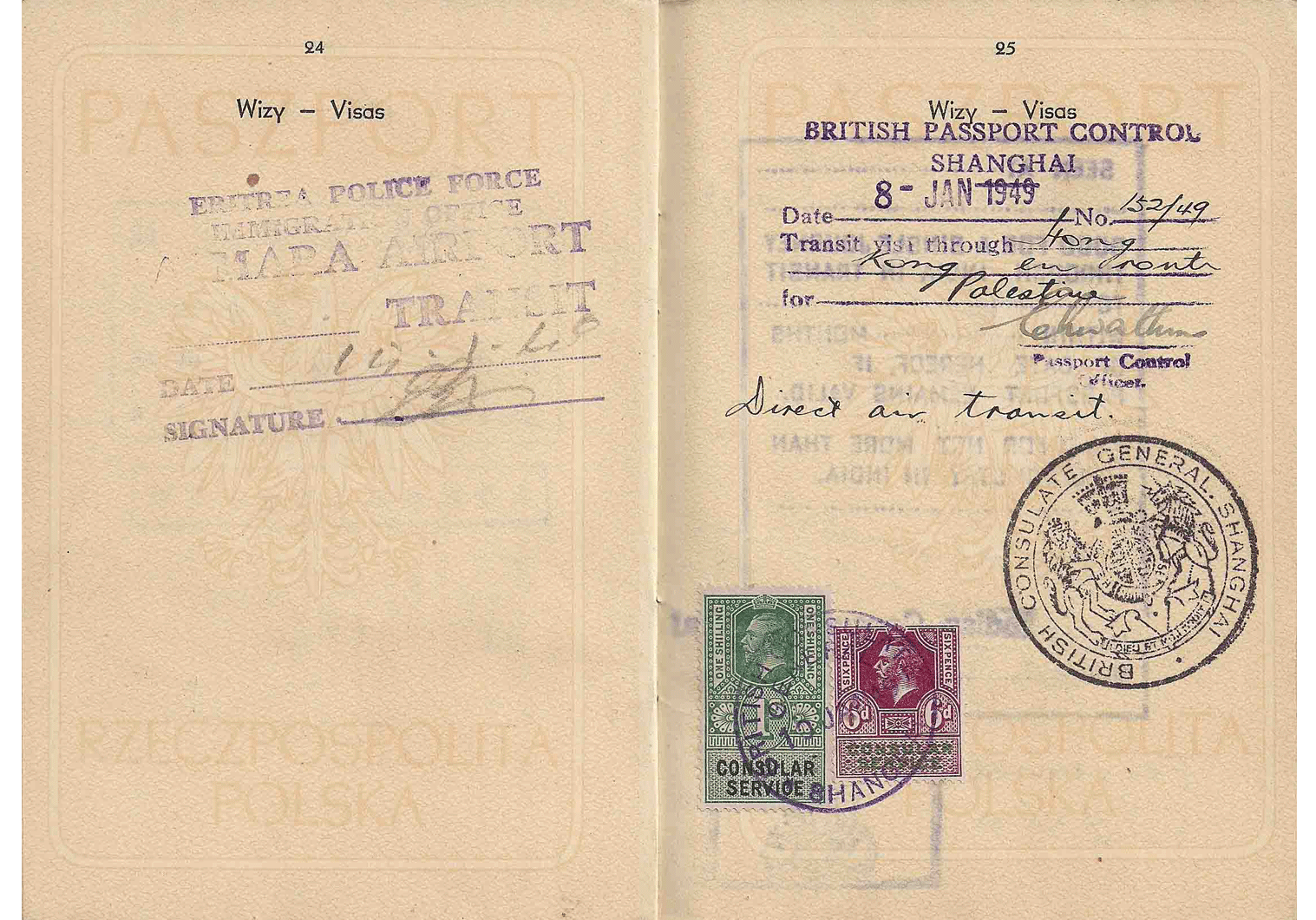

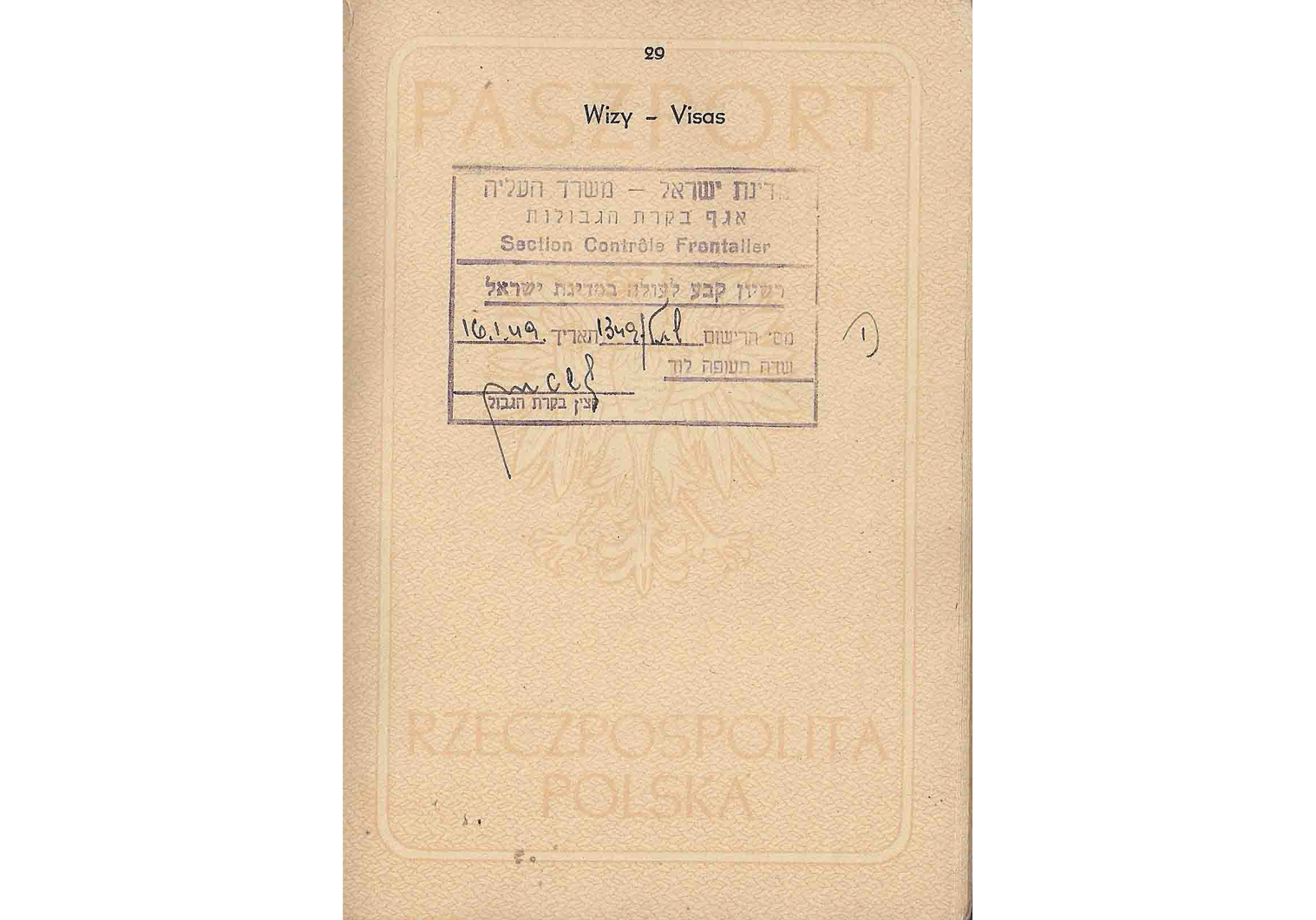

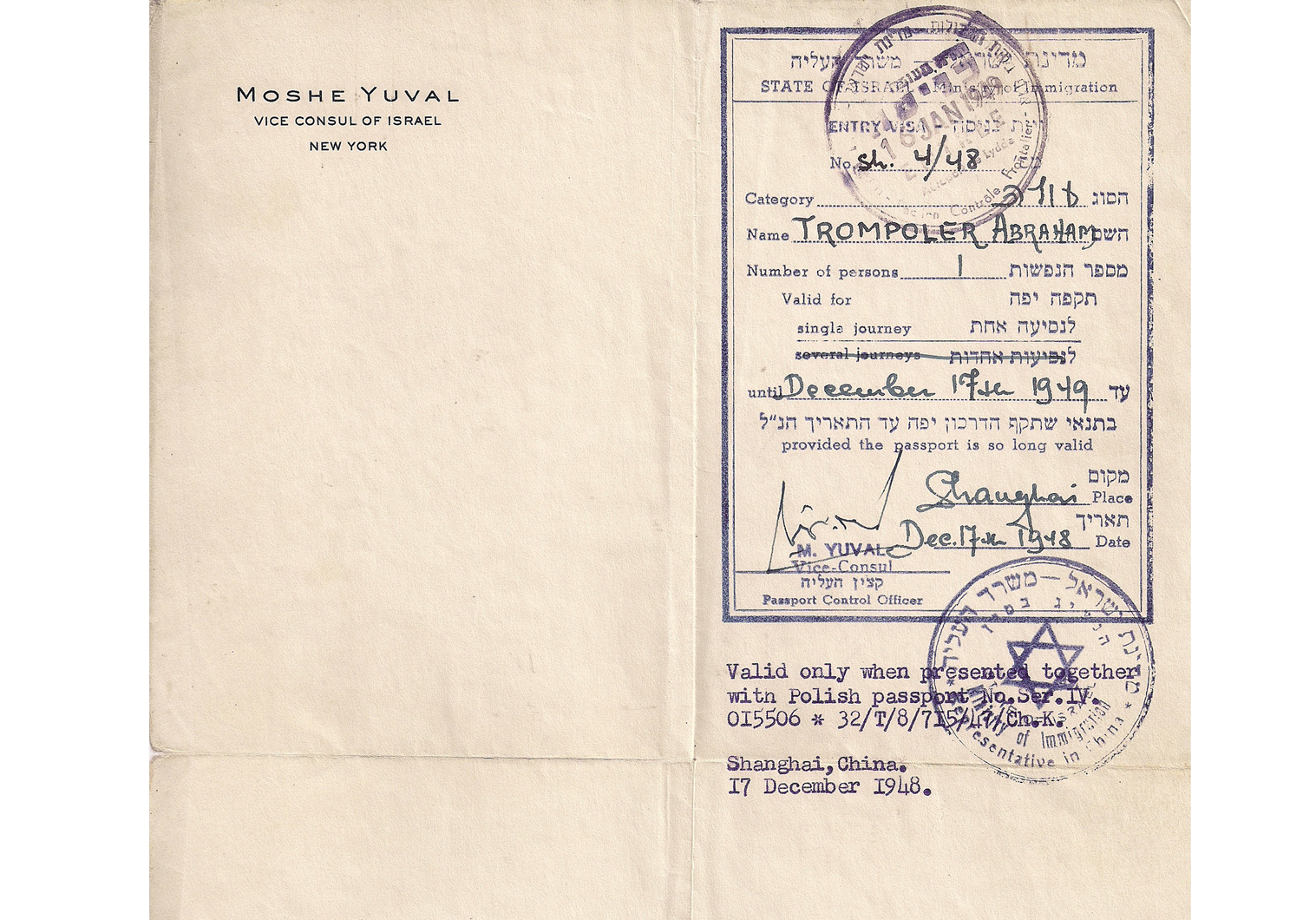

Other visas inside include the transit visas via plane from China to the newly founded State of Israel in 1949. What is special and rather unique is the Israeli visa being issued in China, Shanghai on December 17th 1948. The visa, with the very low SN 4/48 (!) and this can be explained by the fact that it was issued weeks after the first consul arrived in China from the US, diplomat Moshe Yuval (he was posted before to the Israeli consulate in New York and was especially asked to travel to China and assist with the immigration of Jews to the country).

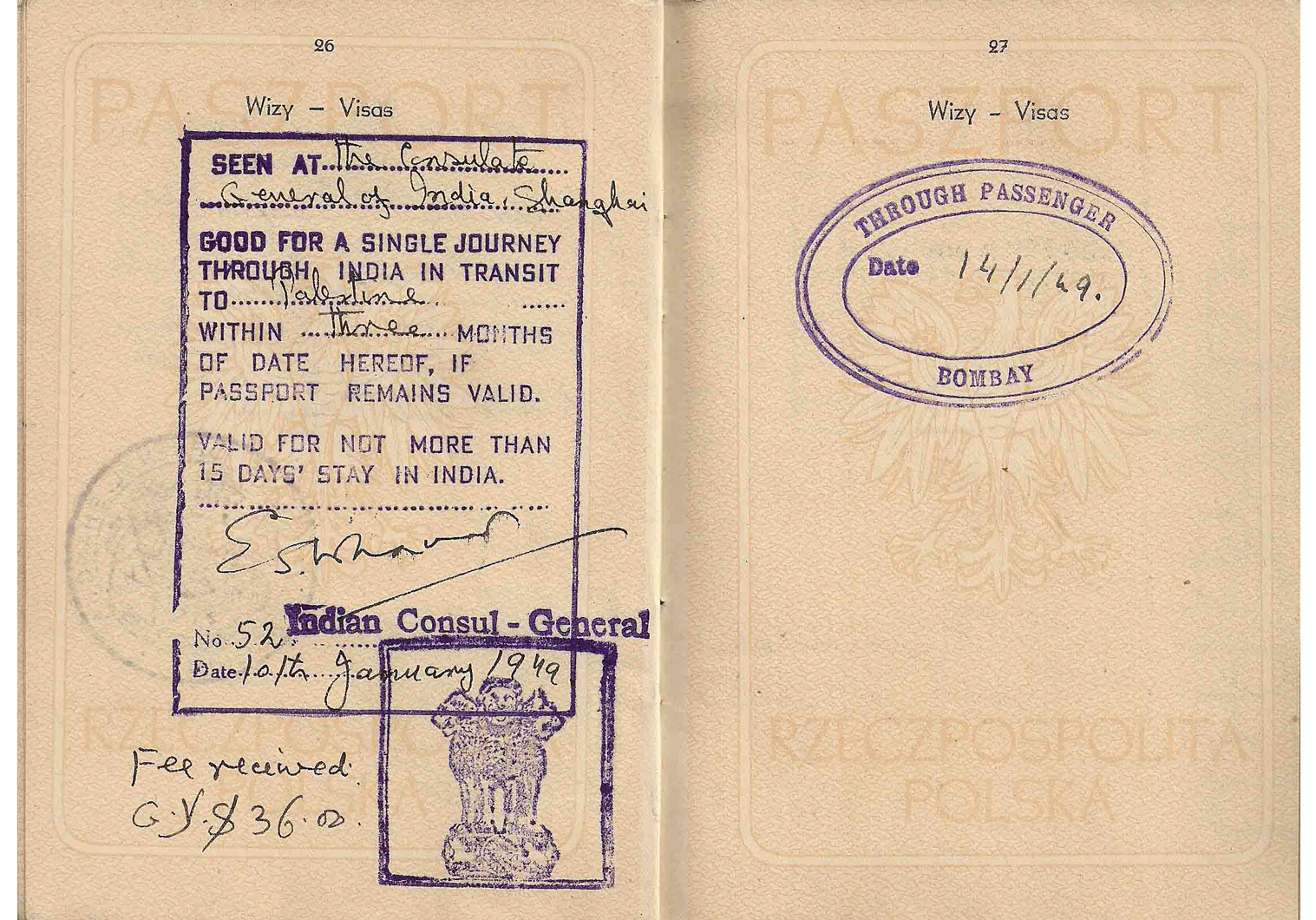

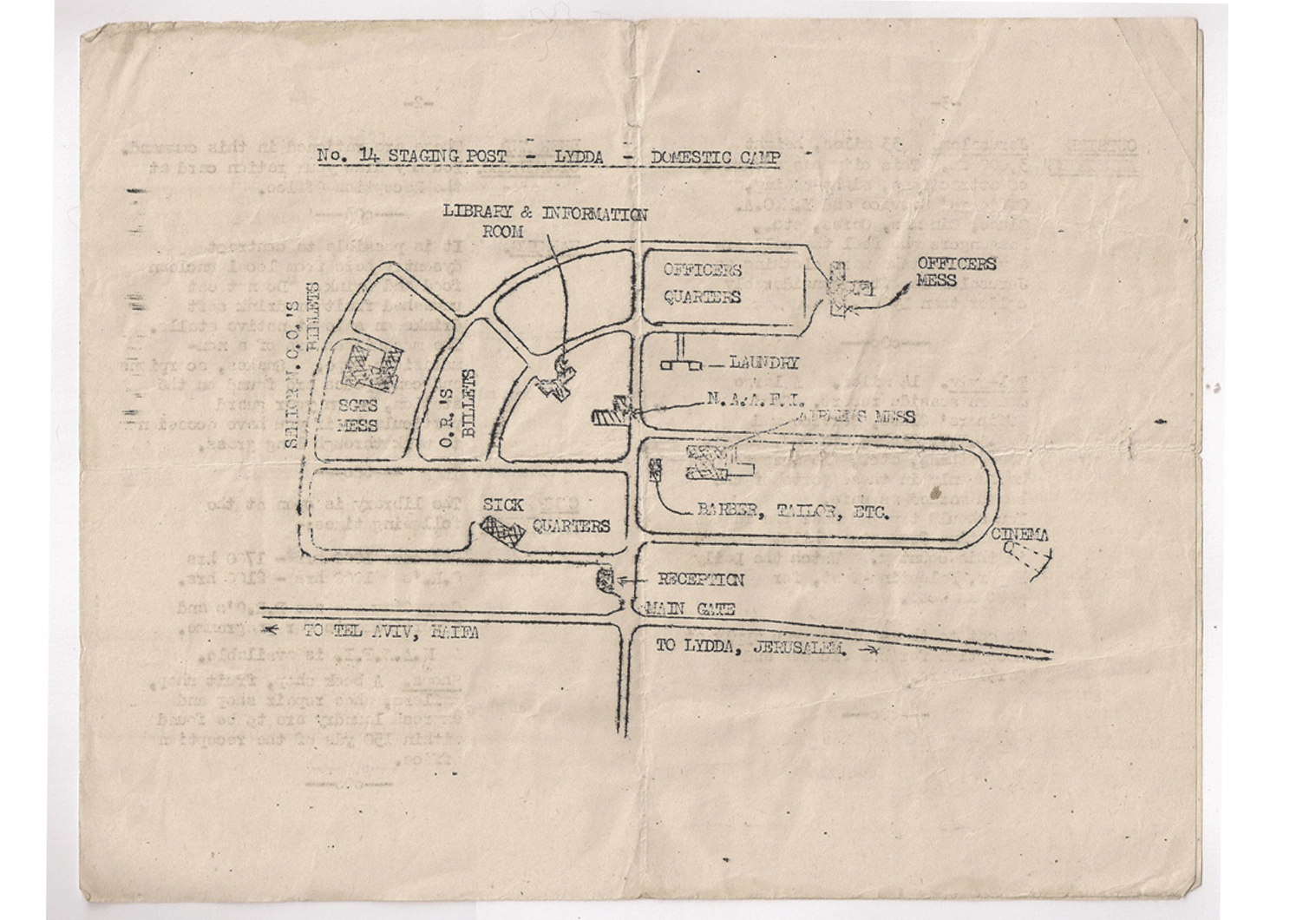

We can locate the British and Indian visas as well inside the passport, used by it’s holder en-route for Lod airport, now Ben Gurion Airport, were his plane touched down on January 16th 1949 (added image of a RAF army pamphlet handed to the staff stationed at the airport of Lod, then Lydda, during World War Two).

I have added images of this document.

Thank you for reading “Our Passports”.