US passport used for China and Manchuria

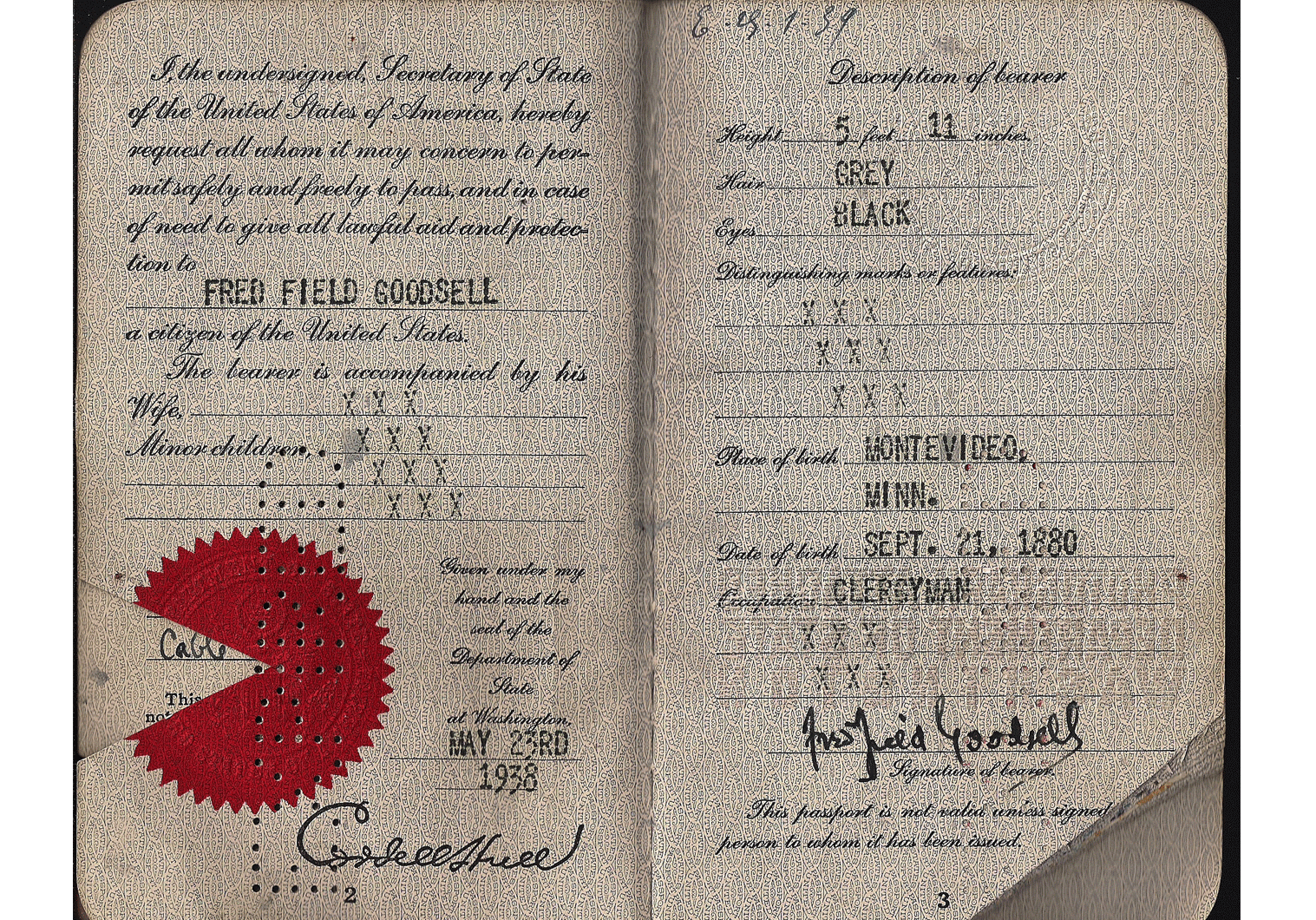

Used by clergyman Fred Field Goodsell.

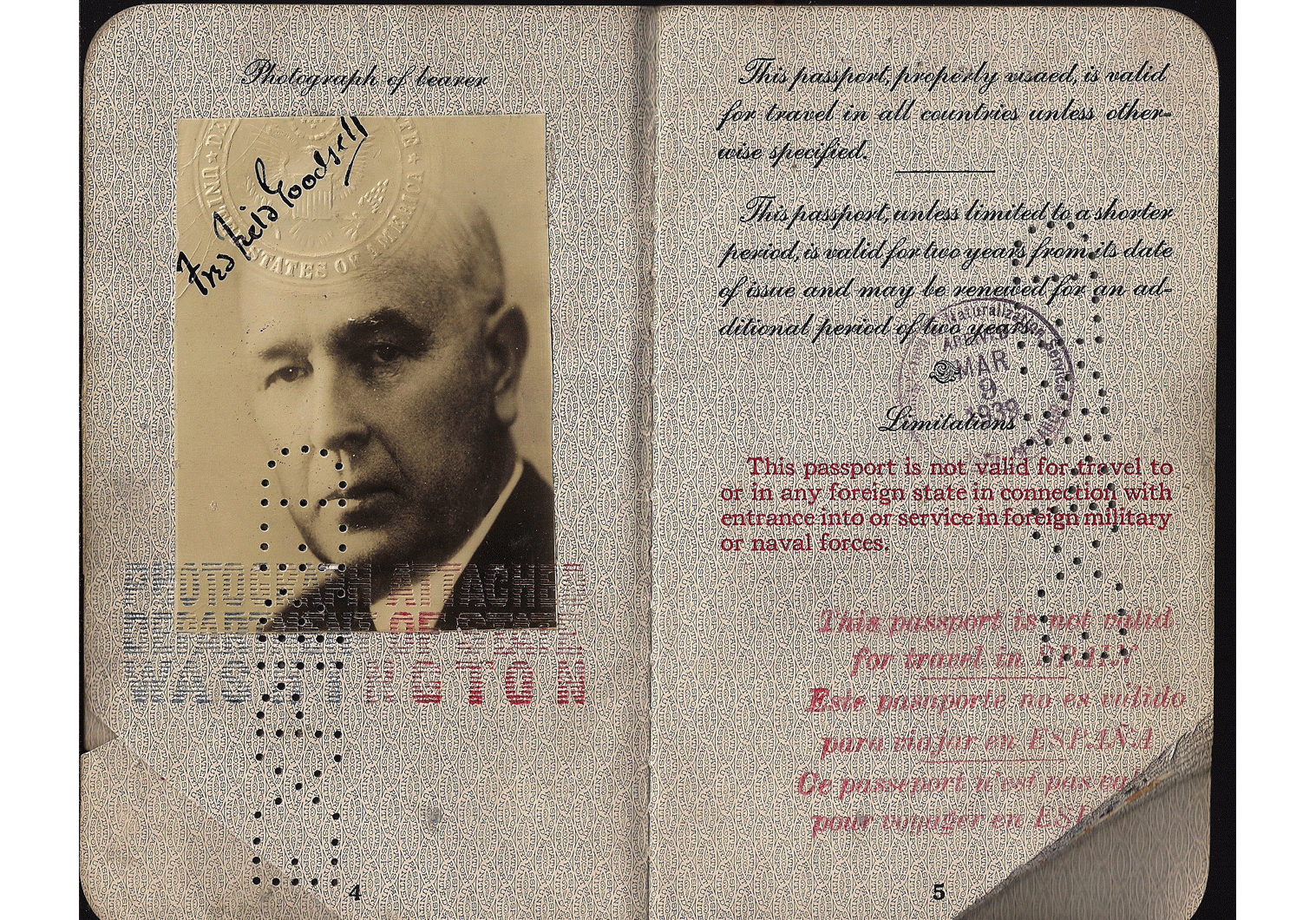

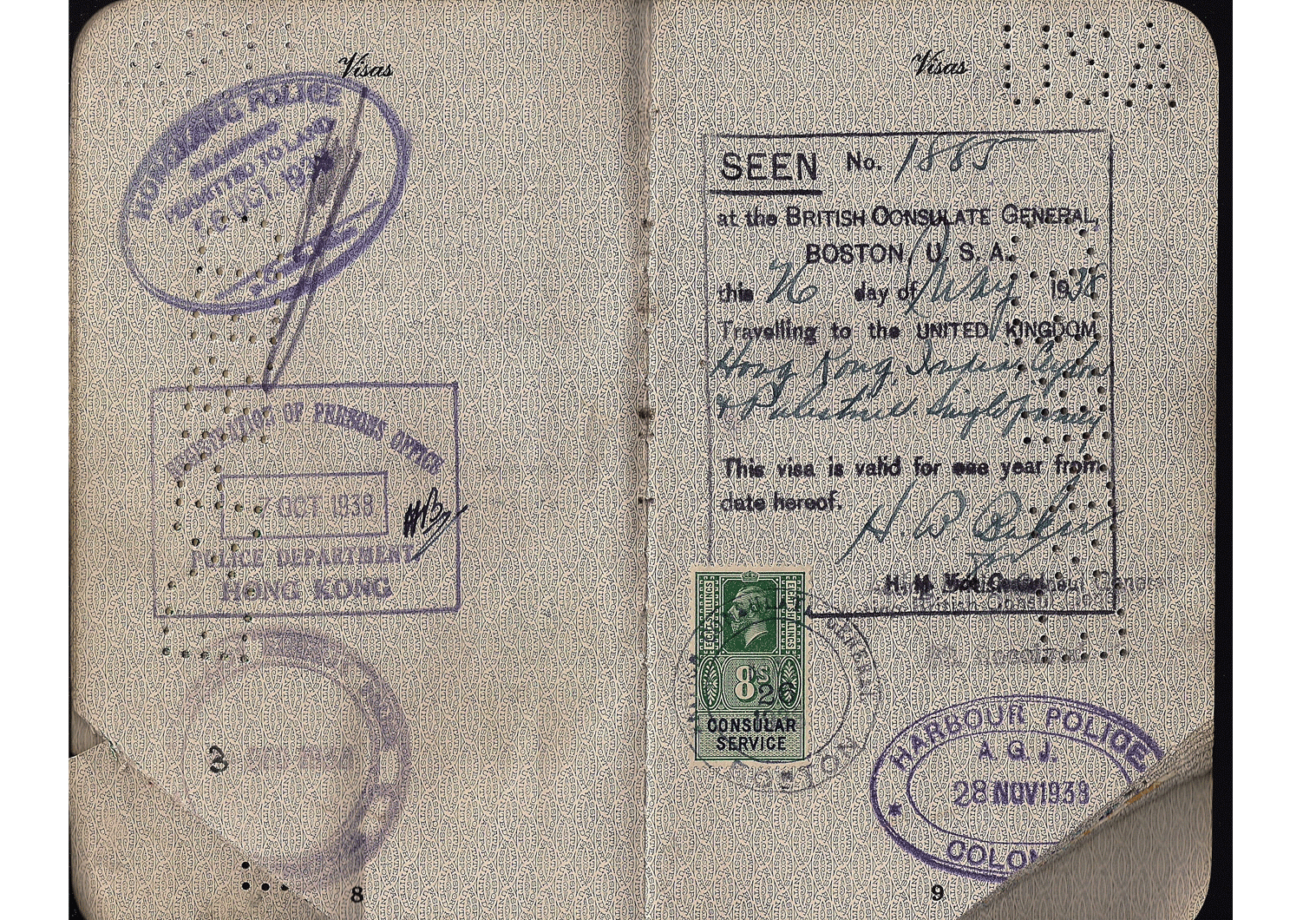

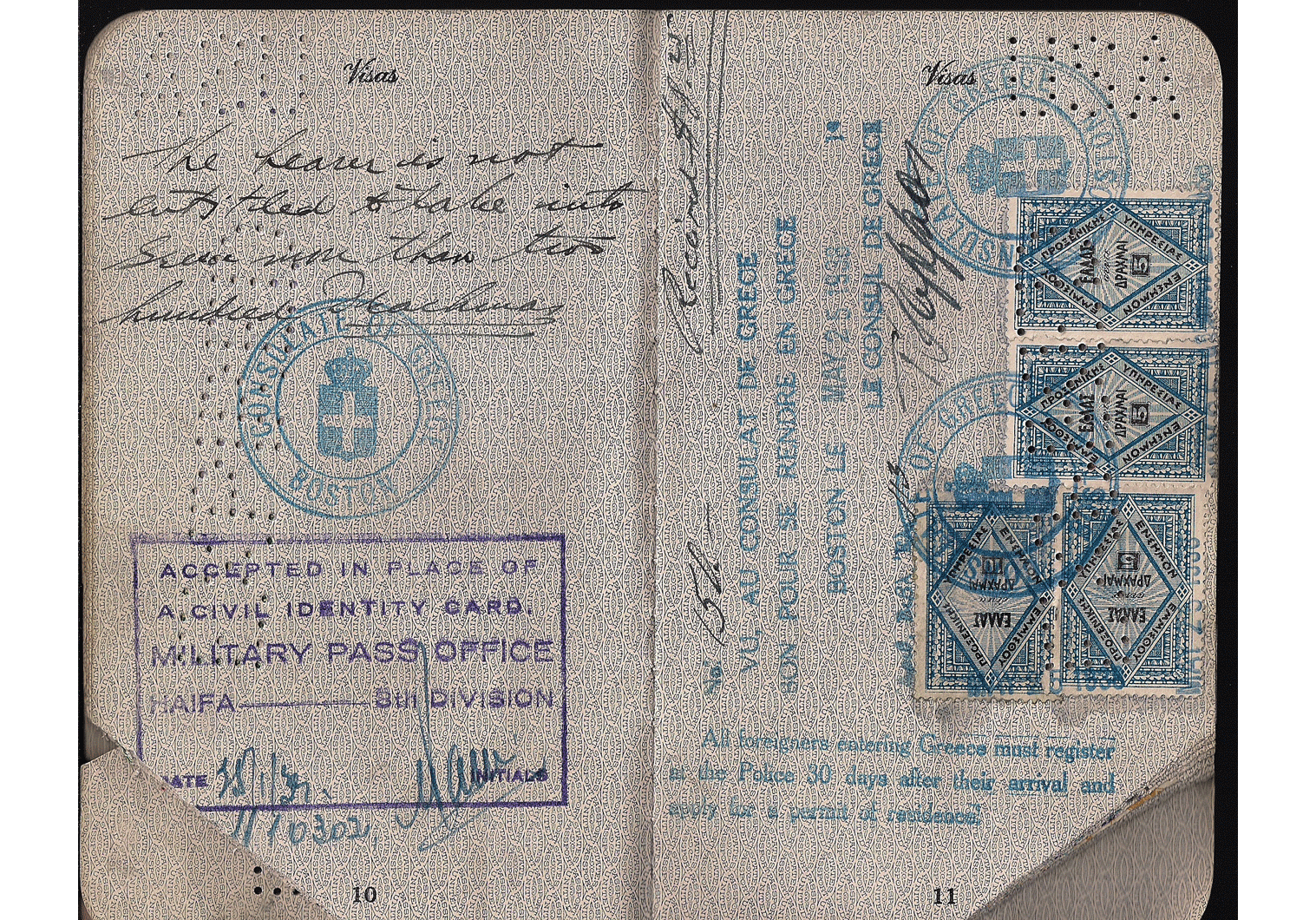

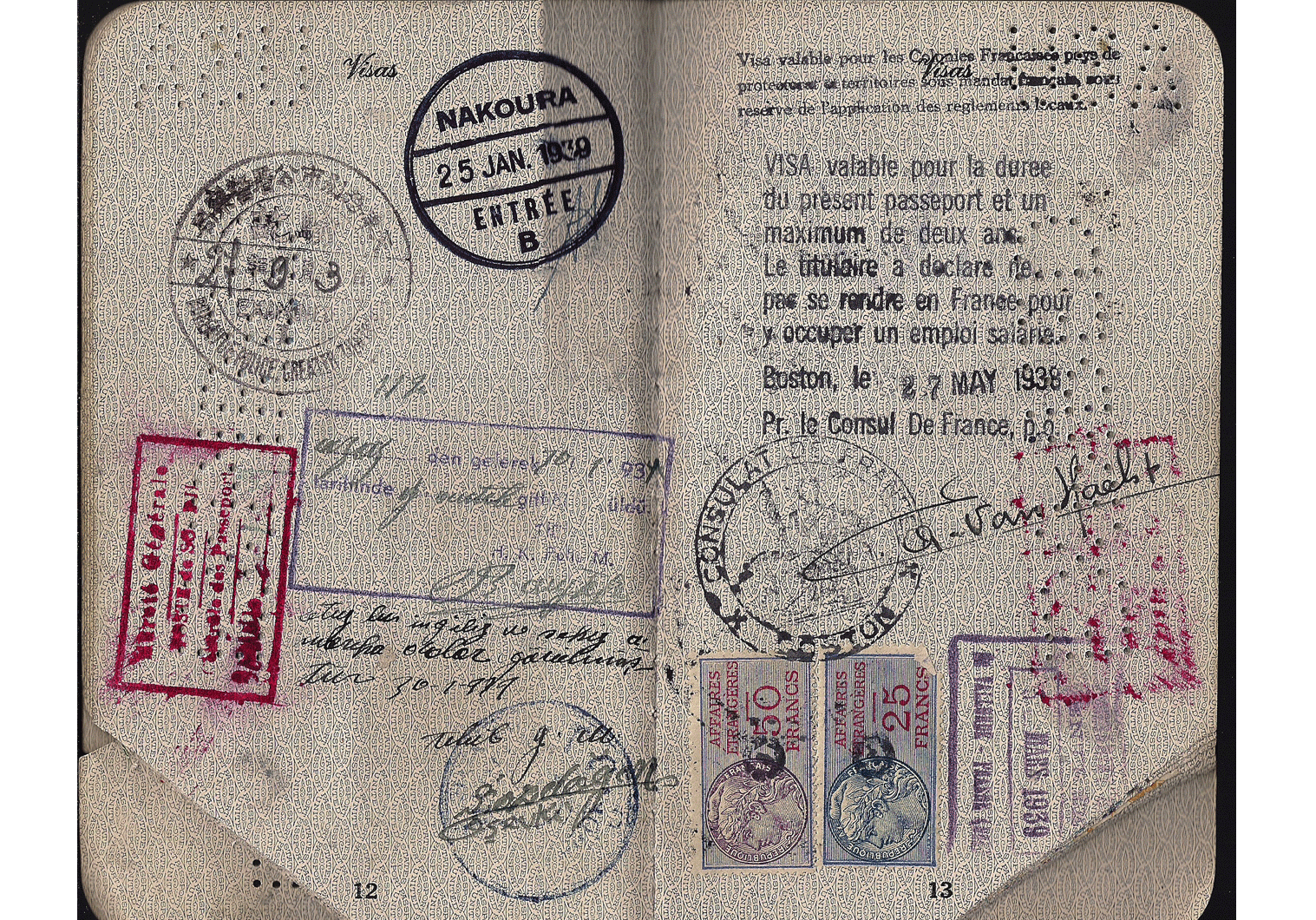

The passport here is an interesting example of pre-WWII usage in areas deemed as “problematic” due to the rise of fascism, Imperialism and occupation around the world. It is therefore an important document for those who would like to research entries into a passport, consisting of visas or permits used during zones of conflict, and in such cases, some of the markings and additions to such travel documents are extra rare because of the time issued and the existence of such bodies or organizations that issued them: in times of war and conflict issuing authorities lasted for a specific period of time, not often long enough to have issued many such visas, so their addition into a passport makes the document important.

During the 1930’s we can locate zones of conflict that had restrictions for entry, either being issued by the occupying forces or by governments abroad, who wanted to safe-guard their citizens thus prohibiting them from entering into specific zones or countries, and could have been permitted ONLY with their mentioned permission inside the bearers passport (such was the cases when passports where stamped with “Not valid for Spain” or China).

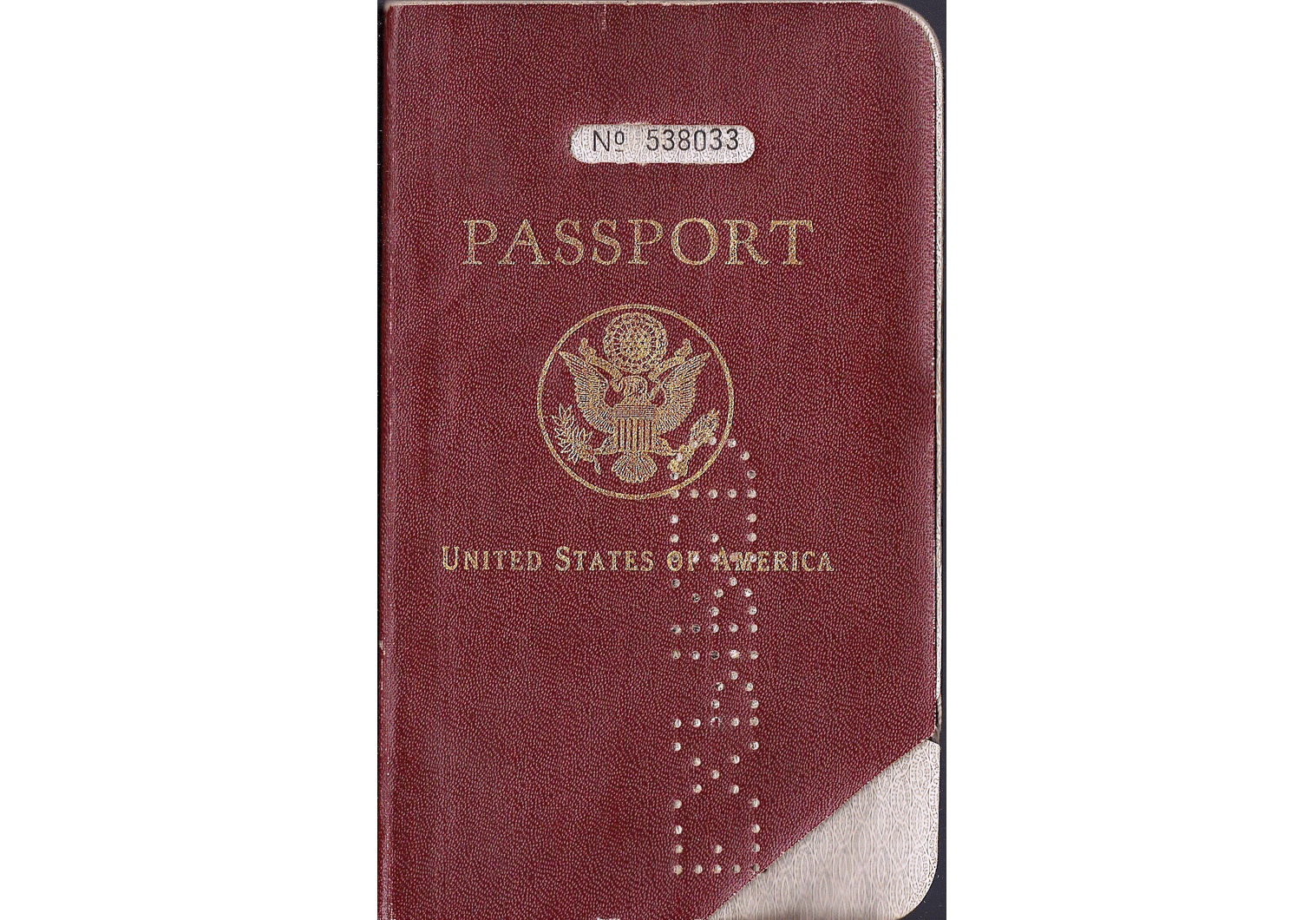

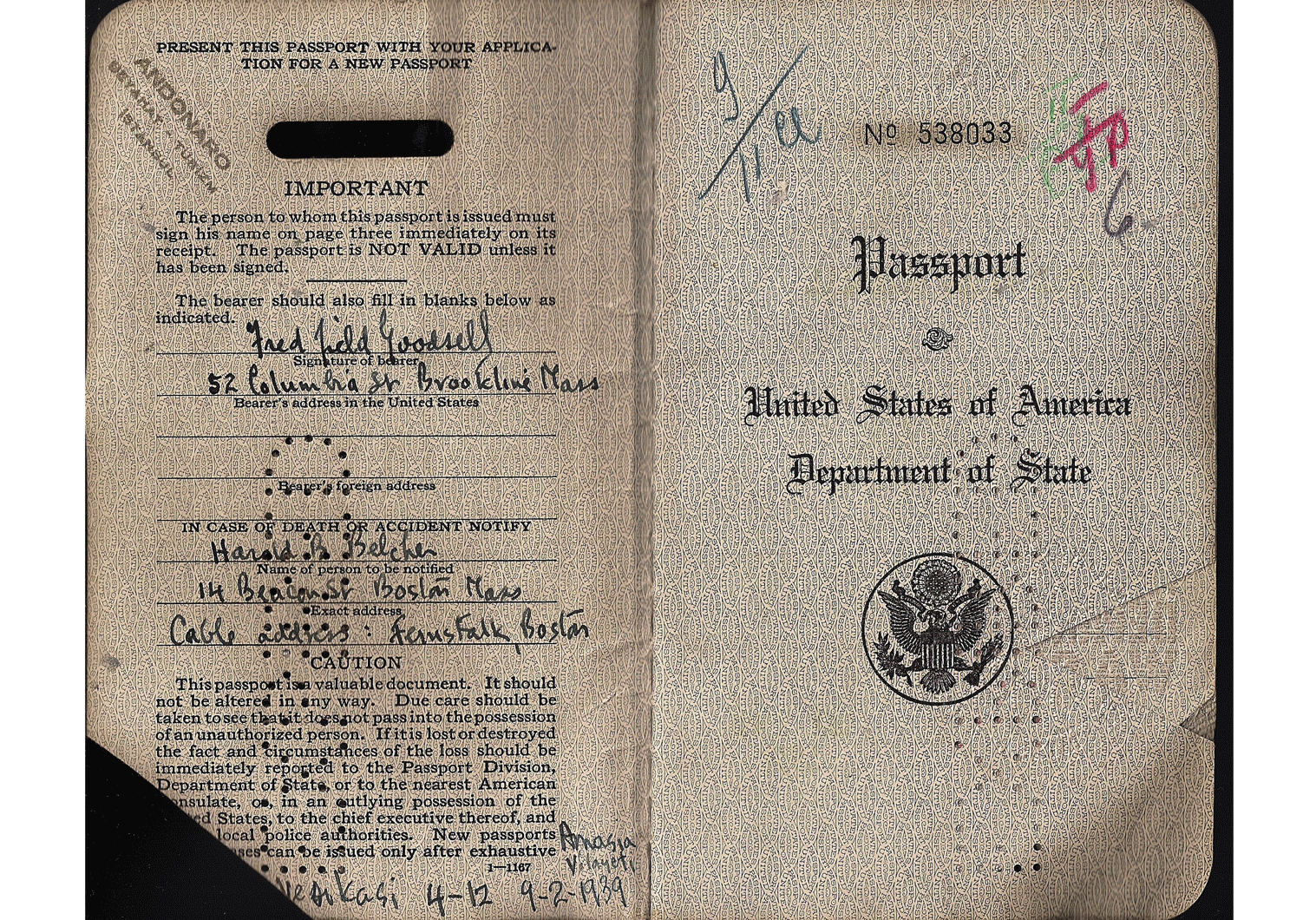

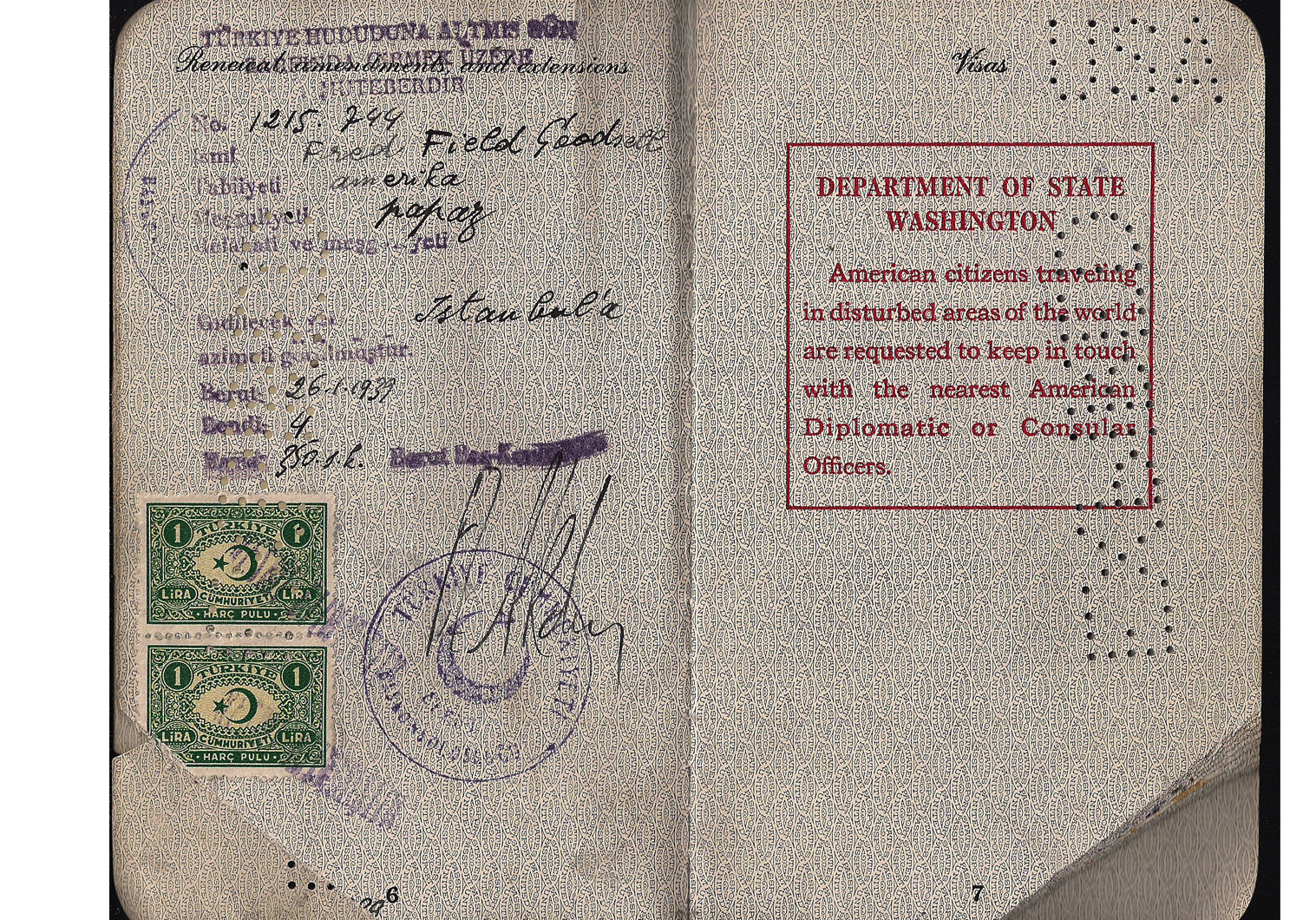

United States passport number 538033 was issued to missionary worker Fred Field Goodsell on May 23rd 1938, who by then was the 1st executive vice-president of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM), and he retired from this position in 1948, continuing to lecture at Boston University and LaSell Junior College in Auburndale. He passed away on August 13th 1976.

Before we go into the passport and issued visas, here is some explanation to the issuing of Manchurian visas:

September 18th 1931 was a crucial date in the history of modern China. From this month onwards, starting with Asia and ending with Europe, events would spiral from a regional conflict into a world war.

The above mentioned date marks the Japanese invasion of North-Eastern China, a region known as Manchuria (a point needs to be made here: prior to the invasion, the Japanese had an enclave in the Dalian peninsula, Port Arthur, called Guan Dong Zhou Ting (关东州厅) ceded to them following the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-1905, which was a Russian naval base).

The Japanese, using it as an excuse, staged an assault on a railway track owned by them, the South Manchurian Railways, later to be known as the Mukden Incident, to invade North-Eastern China. This led to the establishment of Manchukuo. The new state began to function and run like any other country: separate banks were erected (side-by-side to existing Chinese banks), issuing of currency and postal stamps as well. Manchuria became Manchukuo after it “gained” independence on February 18th 1932, with Puyi being its head (from 1908 the last emperor of Imperial China was Puyi. He continued to live in Beijing, the Forbidden City, but was later expelled. He settled in Tianjin city, in a Japanese concession, from 1925-1931. He was declared emperor of the Manchurian Empire in 1934 and his “reign” lasted until 1945, the year Manchuria was liberated by the Red Army). But in fact it was controlled by the military and Japanese officials who actually ran its economy & foreign relations.

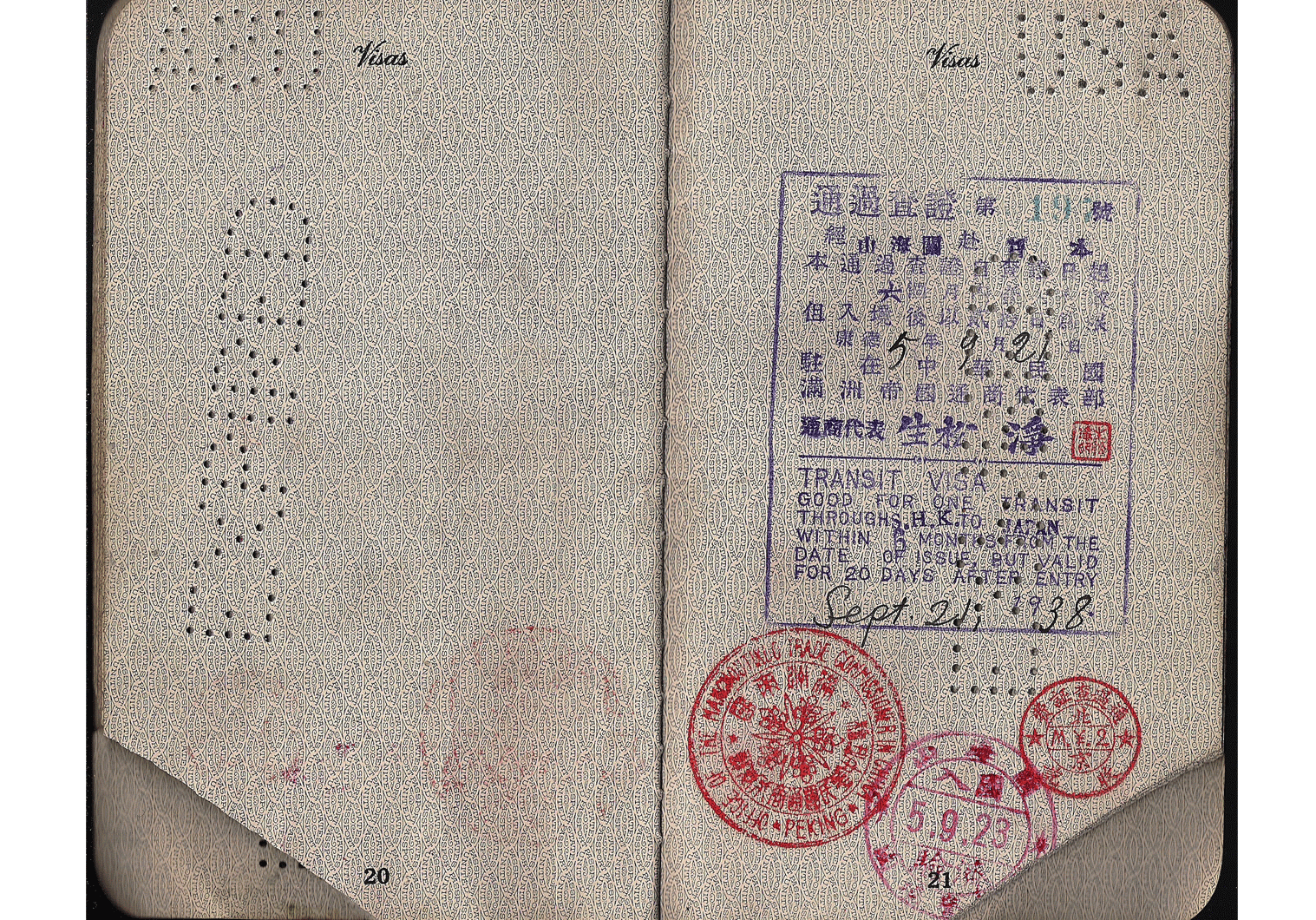

Functioning like a normal country, with foreign representation in Harbin, Manchukuo also opened consulates abroad. Sampled images here will give you a “taste” of such offices abroad, in Germany and in China proper itself (although China did not recognize Manchukuo, the two did open offices in order to promote communications, trade and transportation ties; this could explain the stamps of “ Office of the Manchukuo Trade Commissioner” in Shanghai and Beijing found inside passports).

The passport:

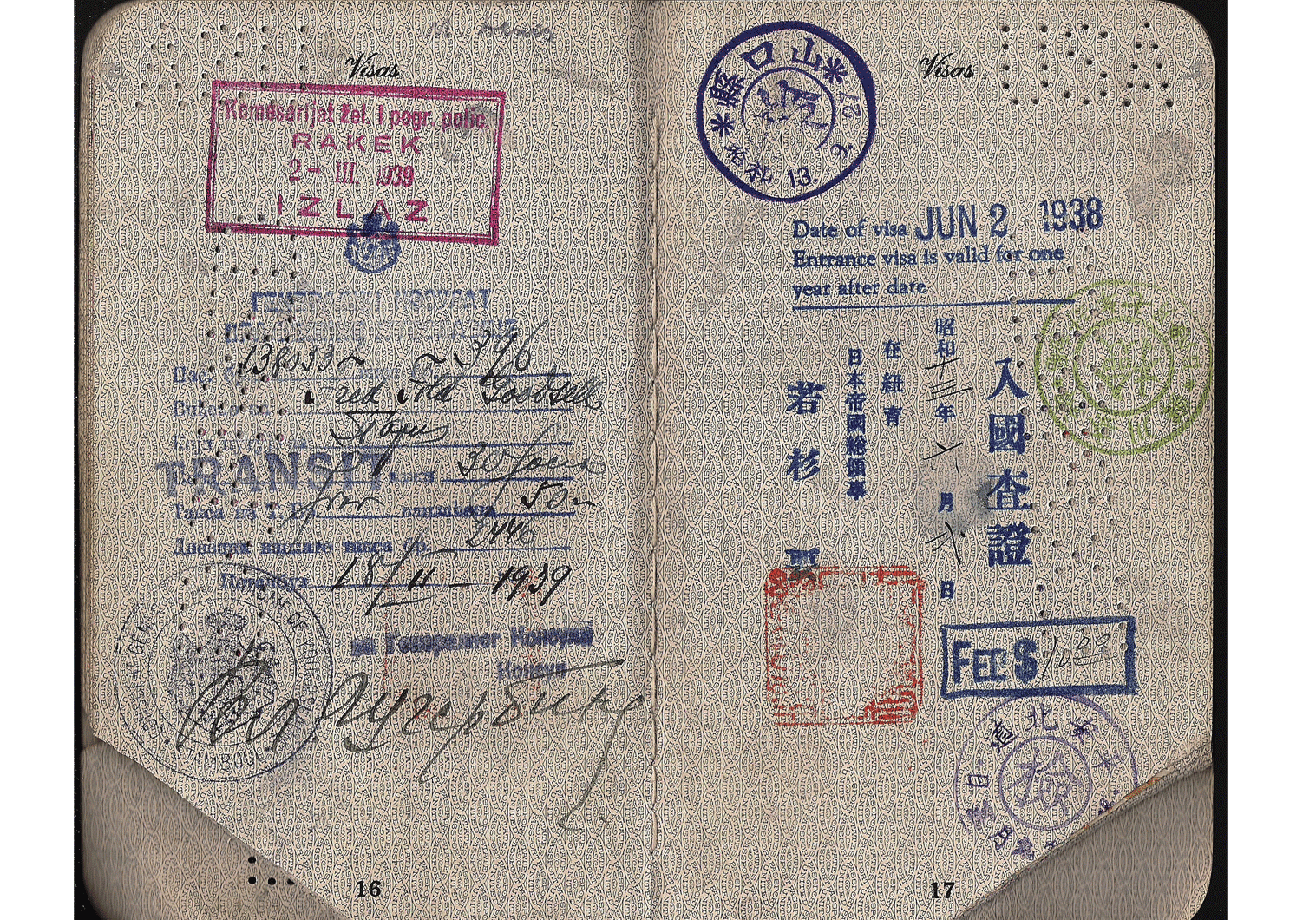

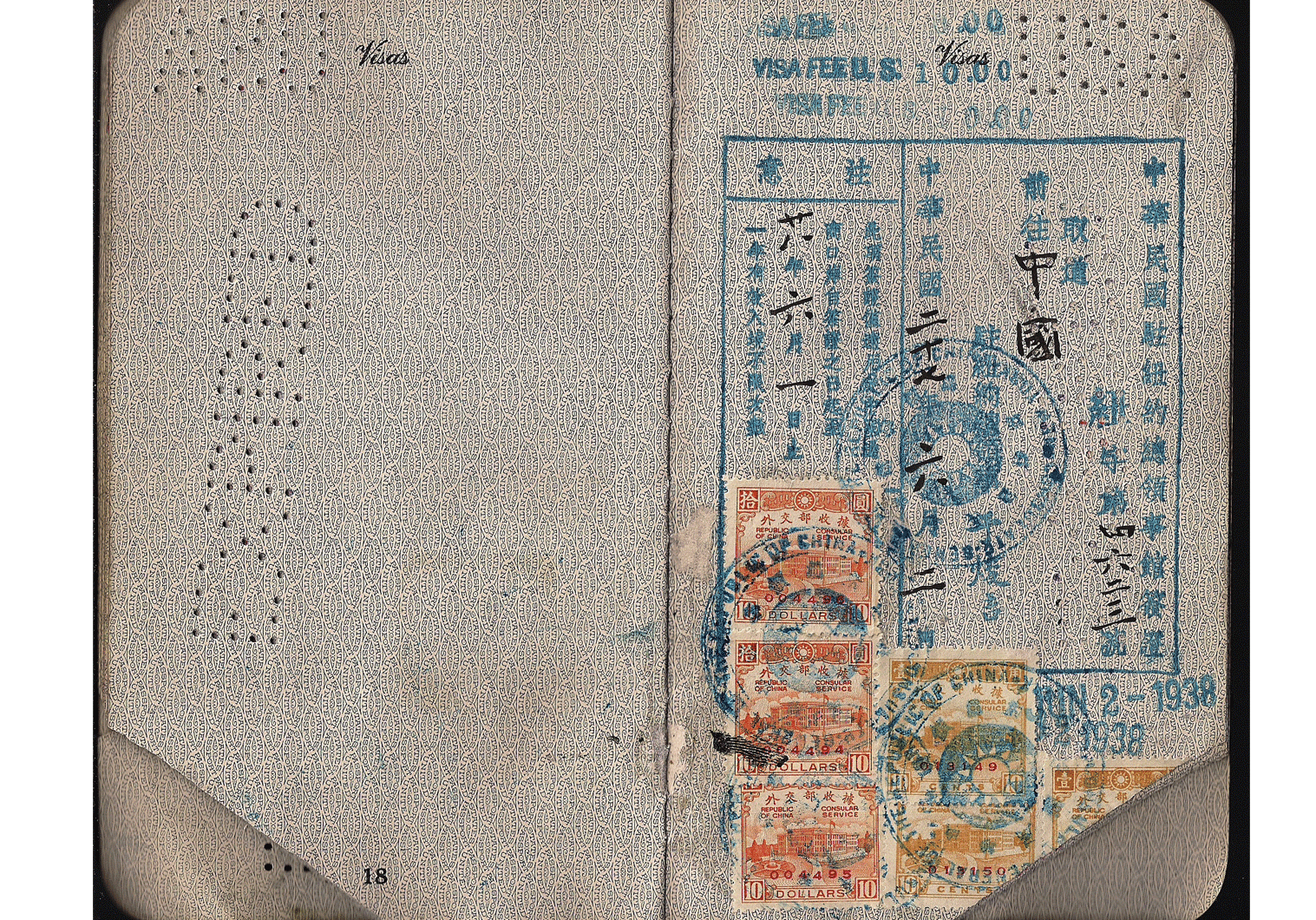

US passport was used to travel to occupied North-Easter China via the important Manchurian visa (No. 19) obtained in Beijing on September 21st 1938, then used 2 days later to enter the disputed area via the southern port border inspection point of Shan Hai Guan (山海关), and as indicated inside the visa to travel to Japan, thus we can find Japanese entry markings for September 27th on page 17 (interesting to note that there is an entry for Tianjin (天津) port from the 3rd, so we can assume that his stay in China was close to 3 weeks about, before leaving to Japan).

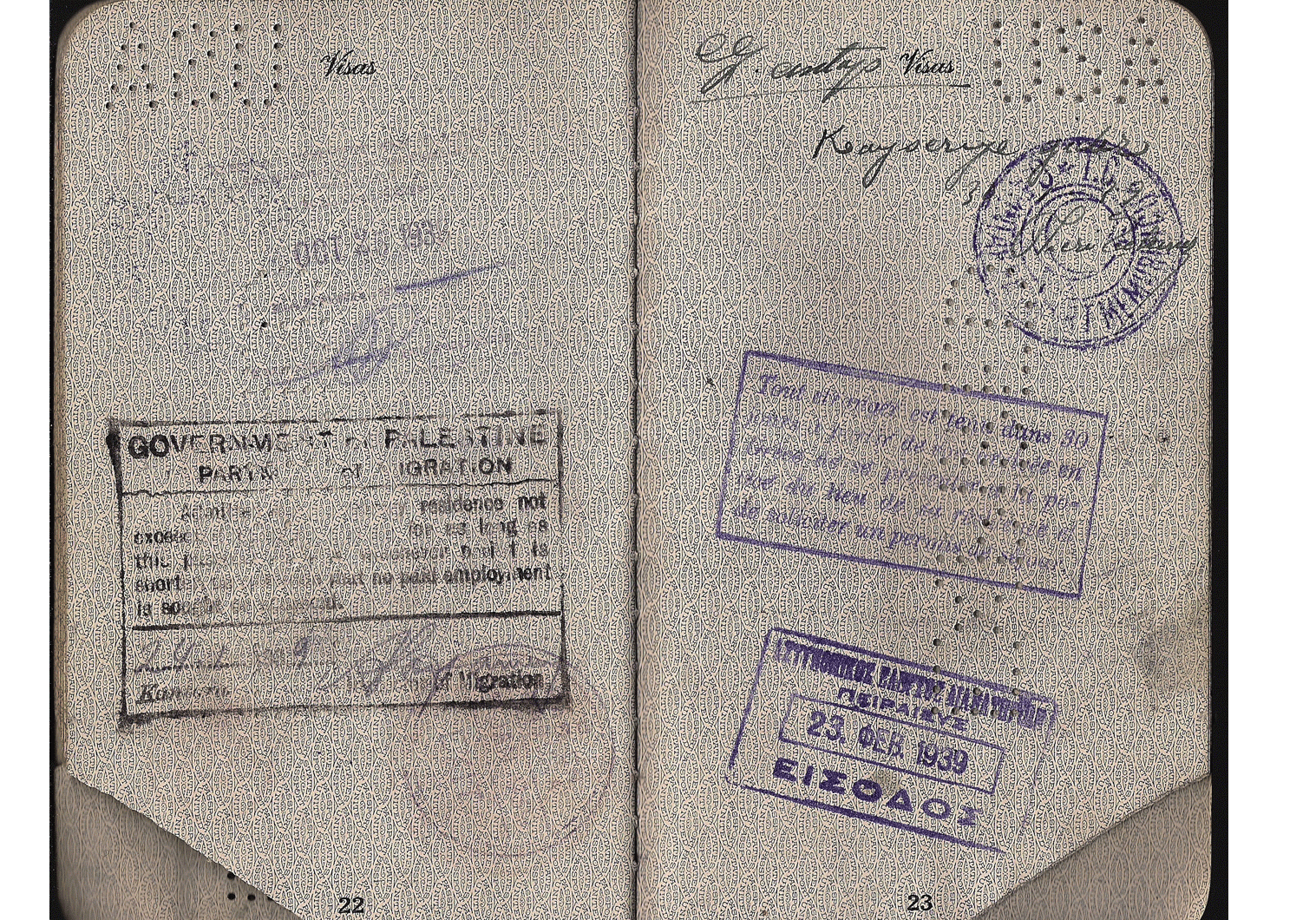

Other entries are for his return back to the US, transiting and visiting other destinations such as British Palestine in 1939 with the uncommon annotation for ID inspection applied by a military check-point and Haifa port from January 25th (on page 10). Other entries are for Turkey, Greece, France and Yugoslavia, all from 1939 en route to his final destination – home.

Thank you for reading “Our Passports”.