Two German stenotypists in war-time Shanghai

One was Jewish and the other an Aryan.

When collecting old passports, one makes a point to check every letter and annotation inside the document. Trying to learn more about the holder and the routes he or she took when traveling aboard. The reasons are as important as the route, because sometimes it would explain the destination and the method one took in doing so.

The two items in this article, in my opinion, were important enough to combine together into one story because of the date, background and profession of the users. I found it to amazing of coincidence that both women were issued a German passport close to the same period of time and both being stenotypists. What also astonished me was the fact that they both ended up in the same city and spent the war years there as well. Though similarity was too close; they would never meet or know of the other at all.

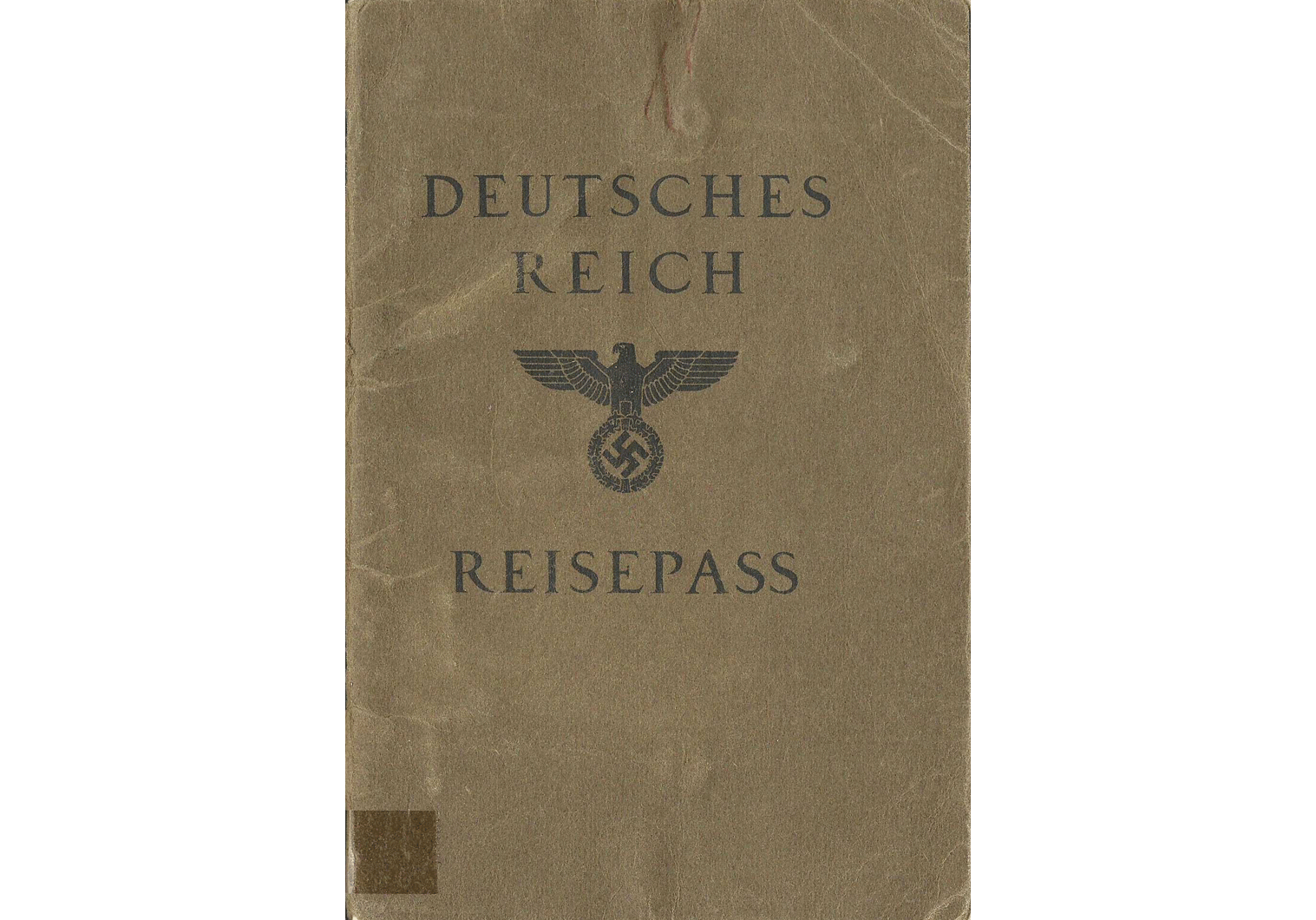

First passport:

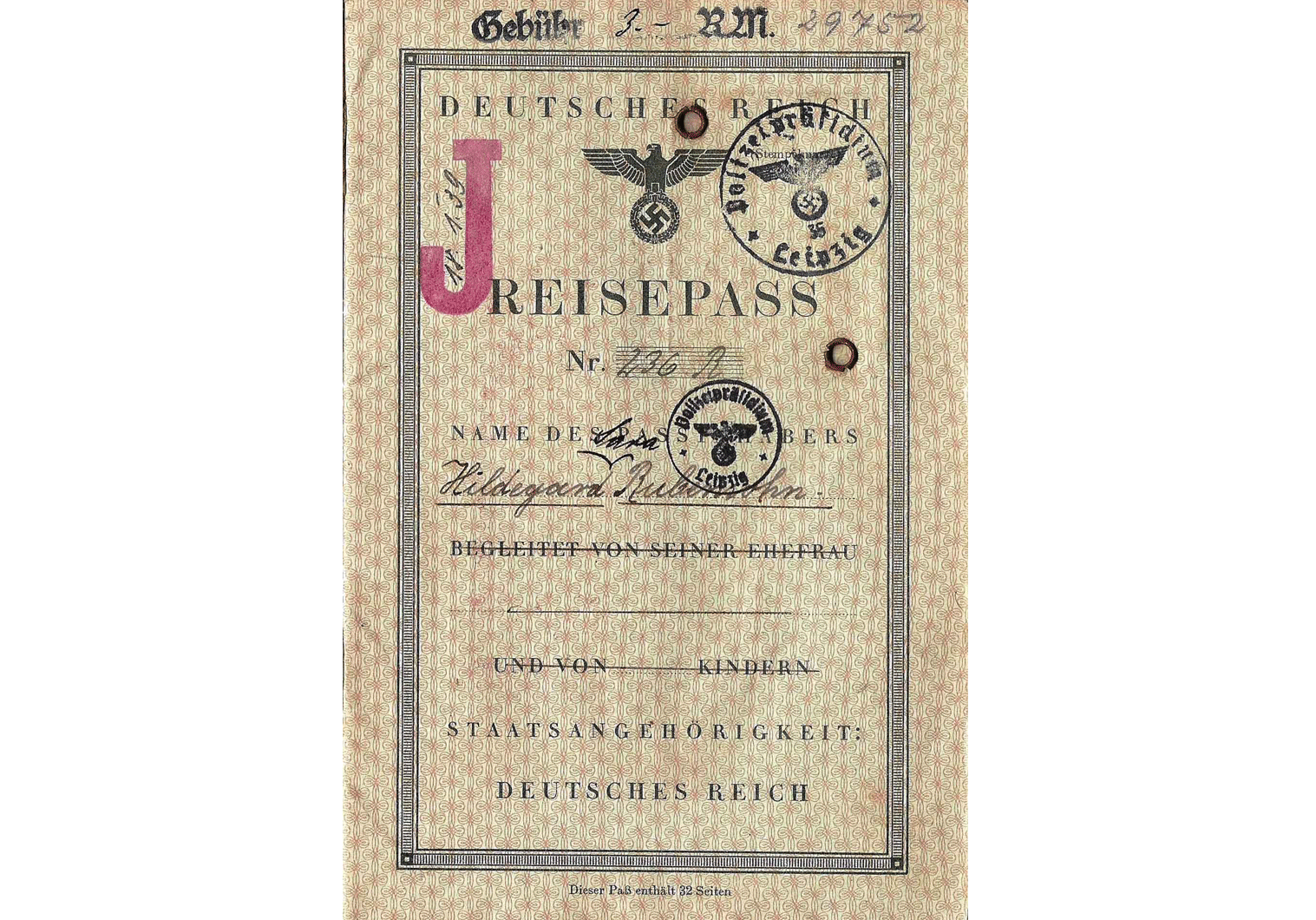

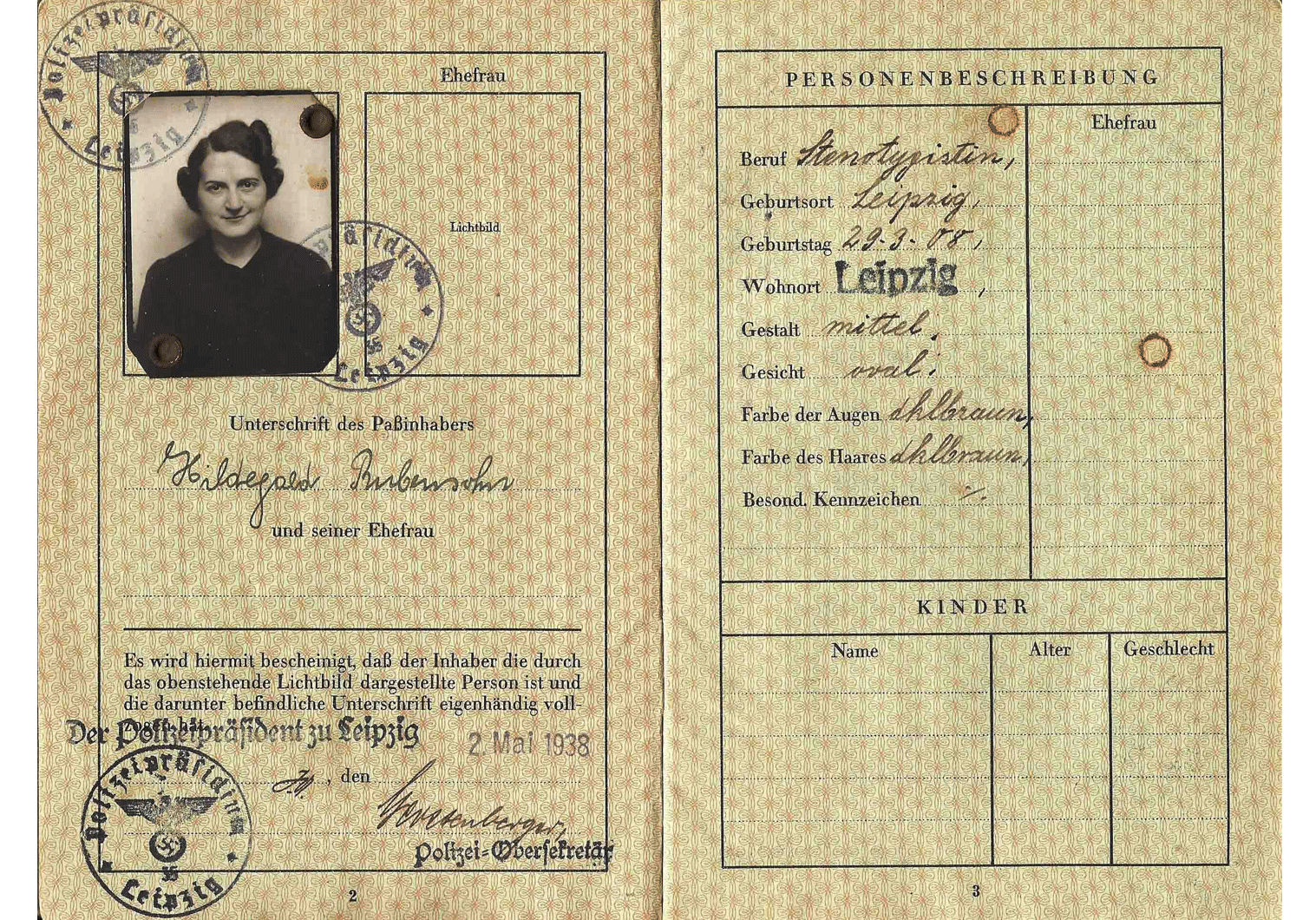

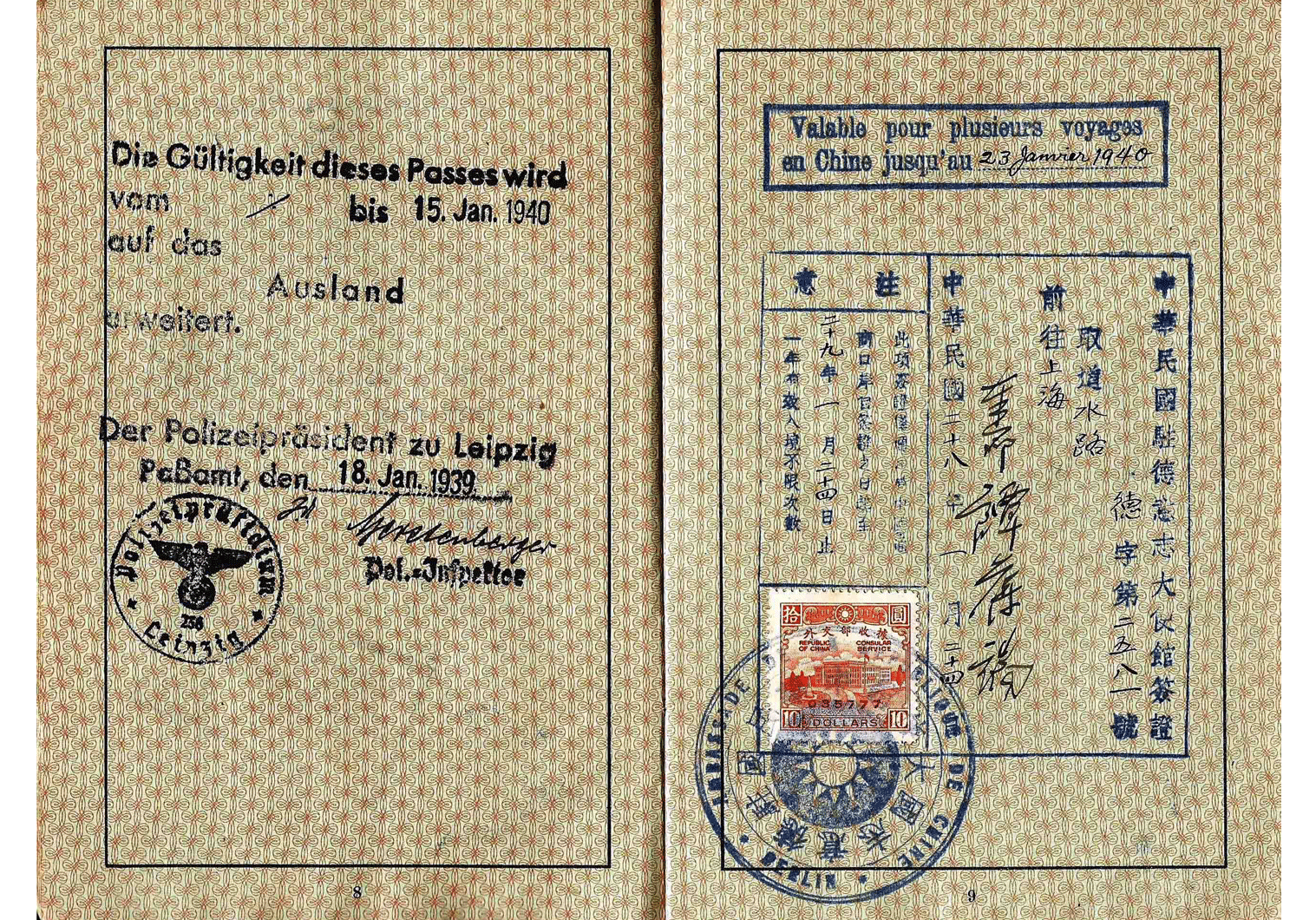

The first passport was issued to 30 year old Hildegard Rubensohn on May 2nd 1938 from Leipzig, and being Jewish she was marked as such, with a large J on the front page on January 18th the following year (Anti-Jewish legislation that started already as early as 1933 also led to Jewish passports having their documents marked as such, and this can be traced to a formal Swiss request from October 5th 1938, and the issuing of such passports lasted until October of 1941, when the German authorities stopped issuing Jews with passports as a means of encouraging and enforcing immigration. In addition, the beginning of 1939 saw another degrading measure that was applied to their Jewish citizens, the forcible addition of the names ISRAEL and SARA. All these means were done in order to enable other countries to recognize when a Jews was trying to enter the country or apply for a visa at a consulate).

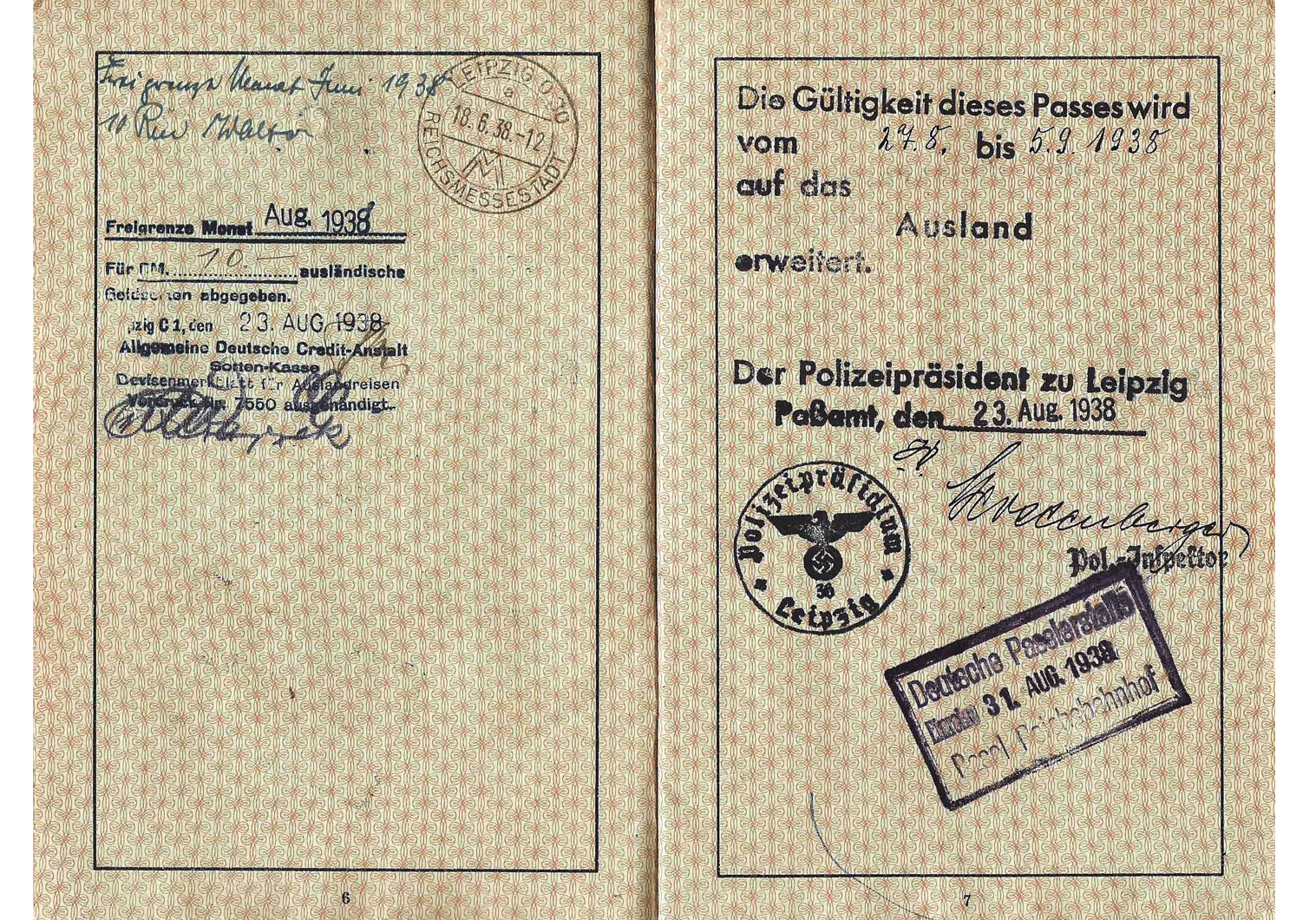

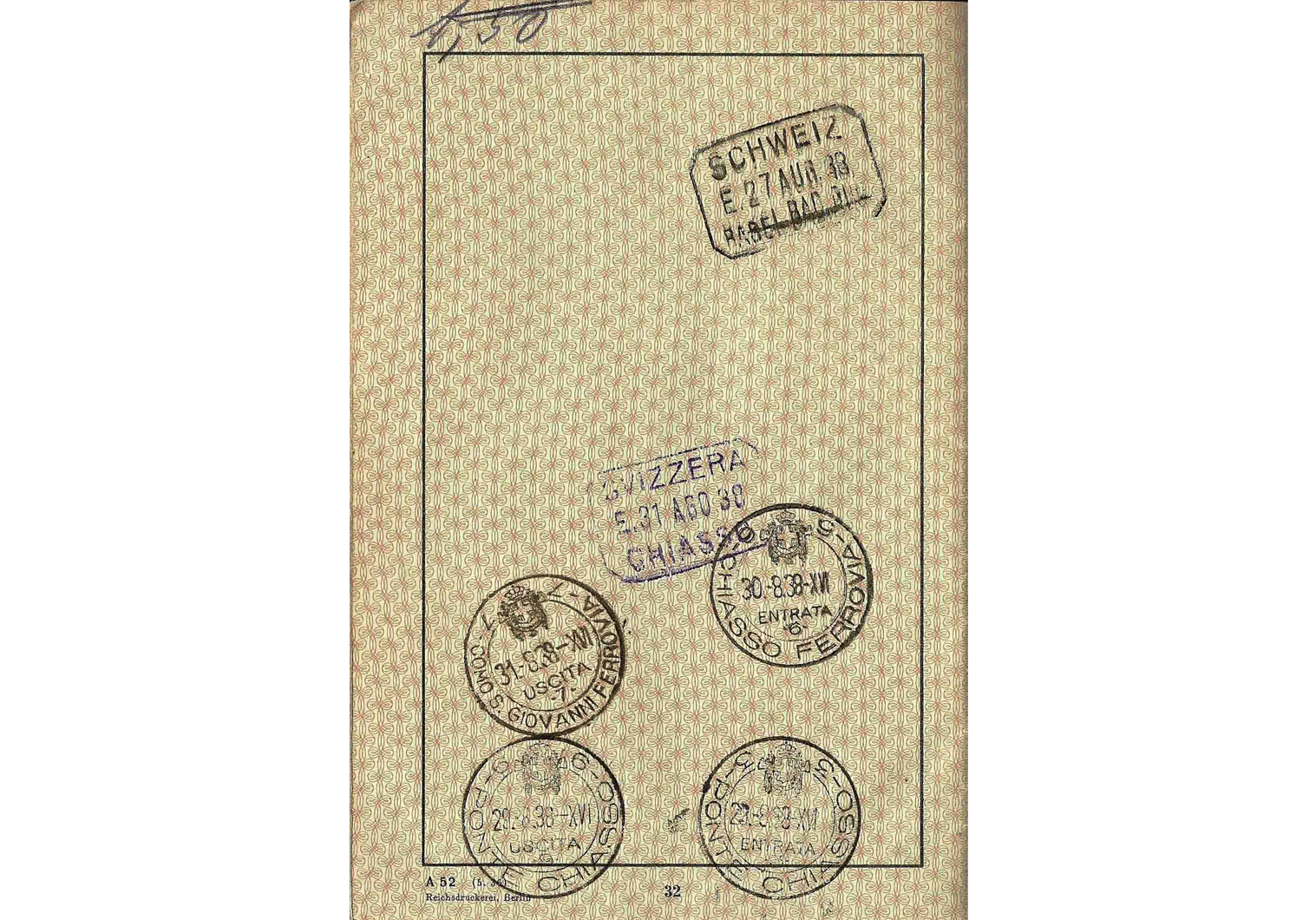

Hildegard originally made use of the passport for brief visits to Italy and Switzerland. Her document was valid for 5 years but another control measure was applied to Jewish passport holders: validity limited for a short period of 1 year only, a means that was meant to trace and control the Jews and making them always apply and register for a new passport or making an extension. We can see this on pages 4, 7 & 8 with the extra Police annotations and amendments.

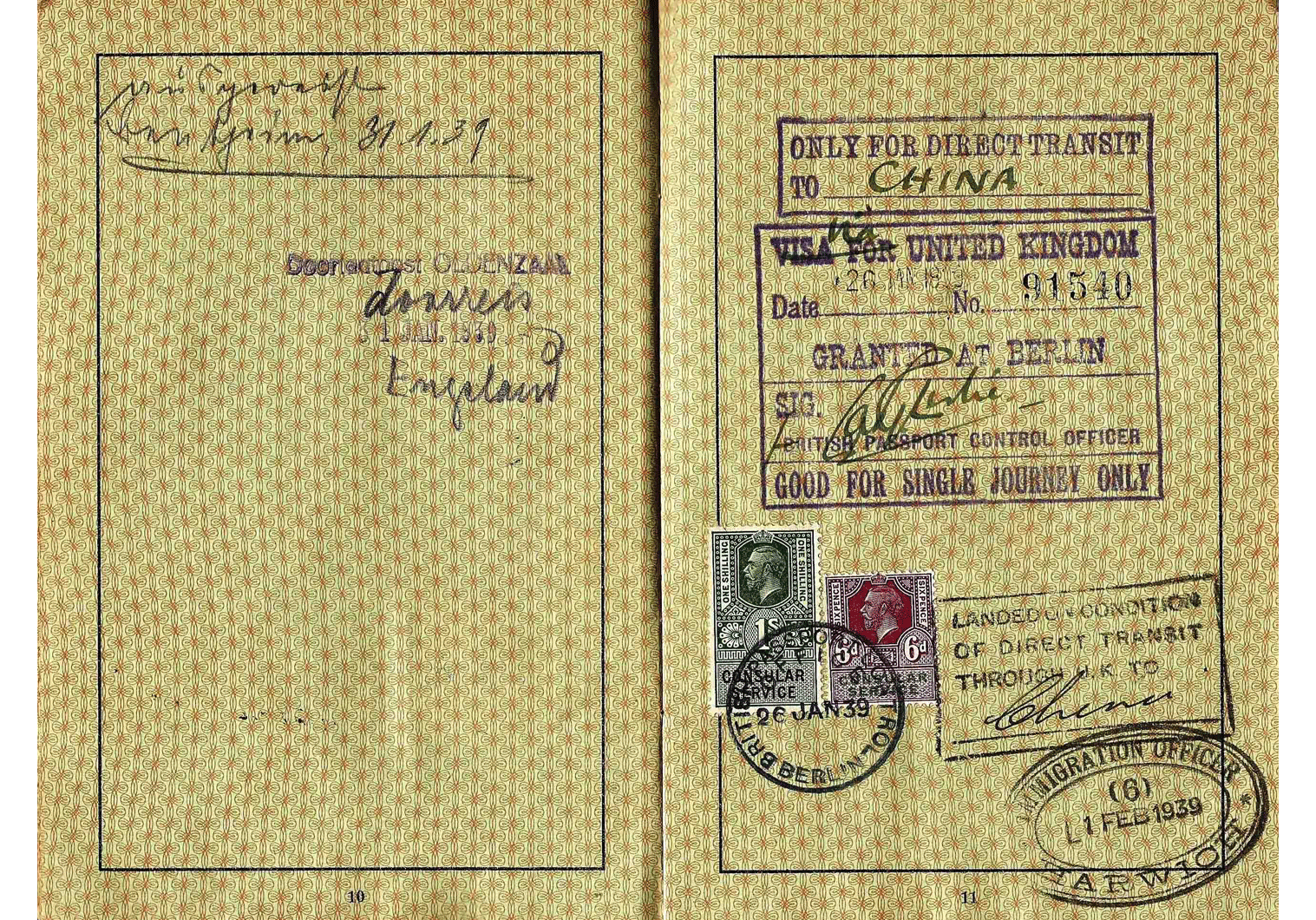

On January 24th she obtained her multiple-entry visa for China from the embassy in Berlin, visa issued by first secretary Tan Baoduan, with the transit route indicated through Siberia. At the end she exited Germany though Holland on January 31st where she boarded a boat in the UK (visa issued 5 days earlier also at Berlin) that took her past Colombo on February 28th, arriving in Shanghai over a week later.

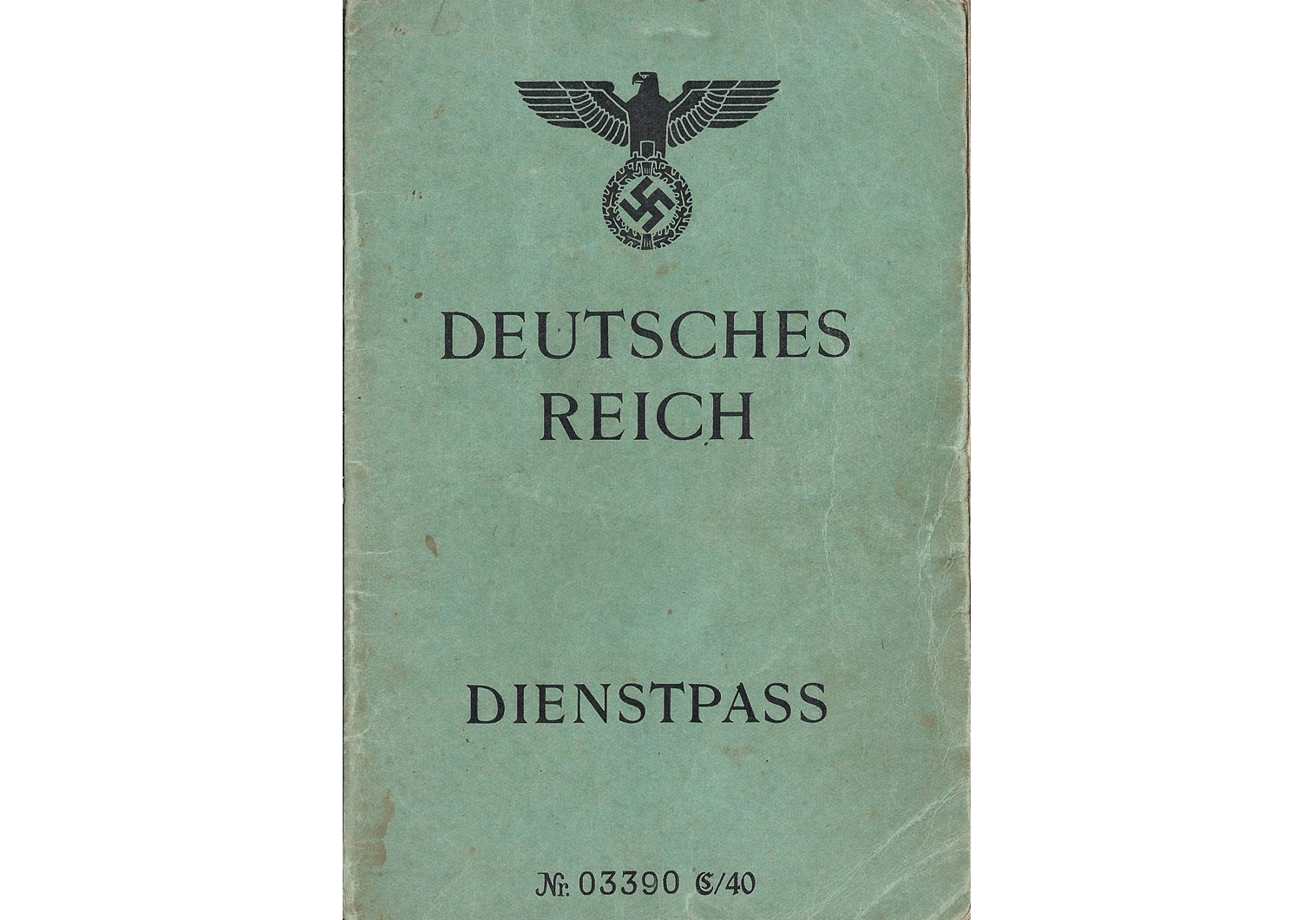

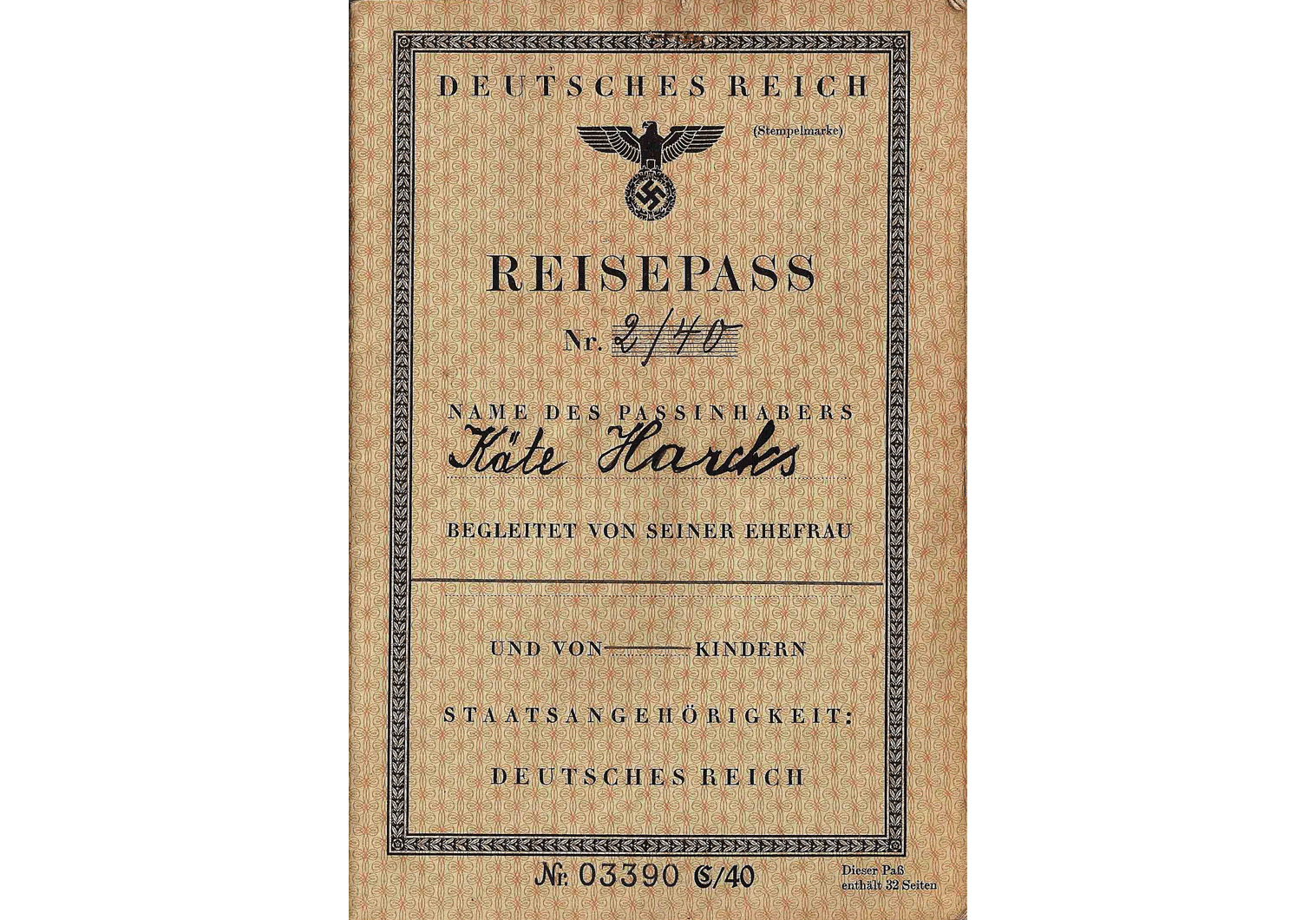

Second Passport:

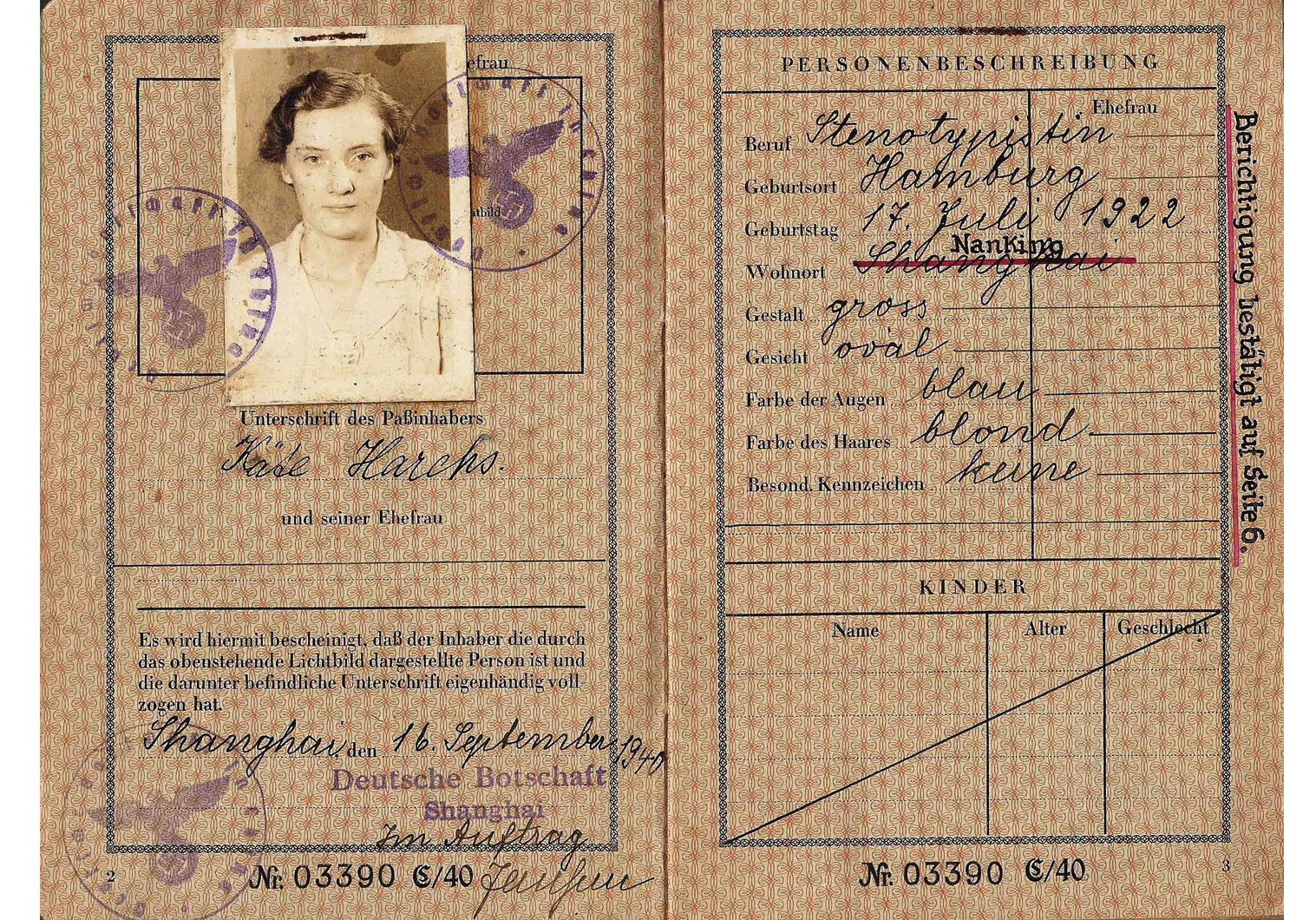

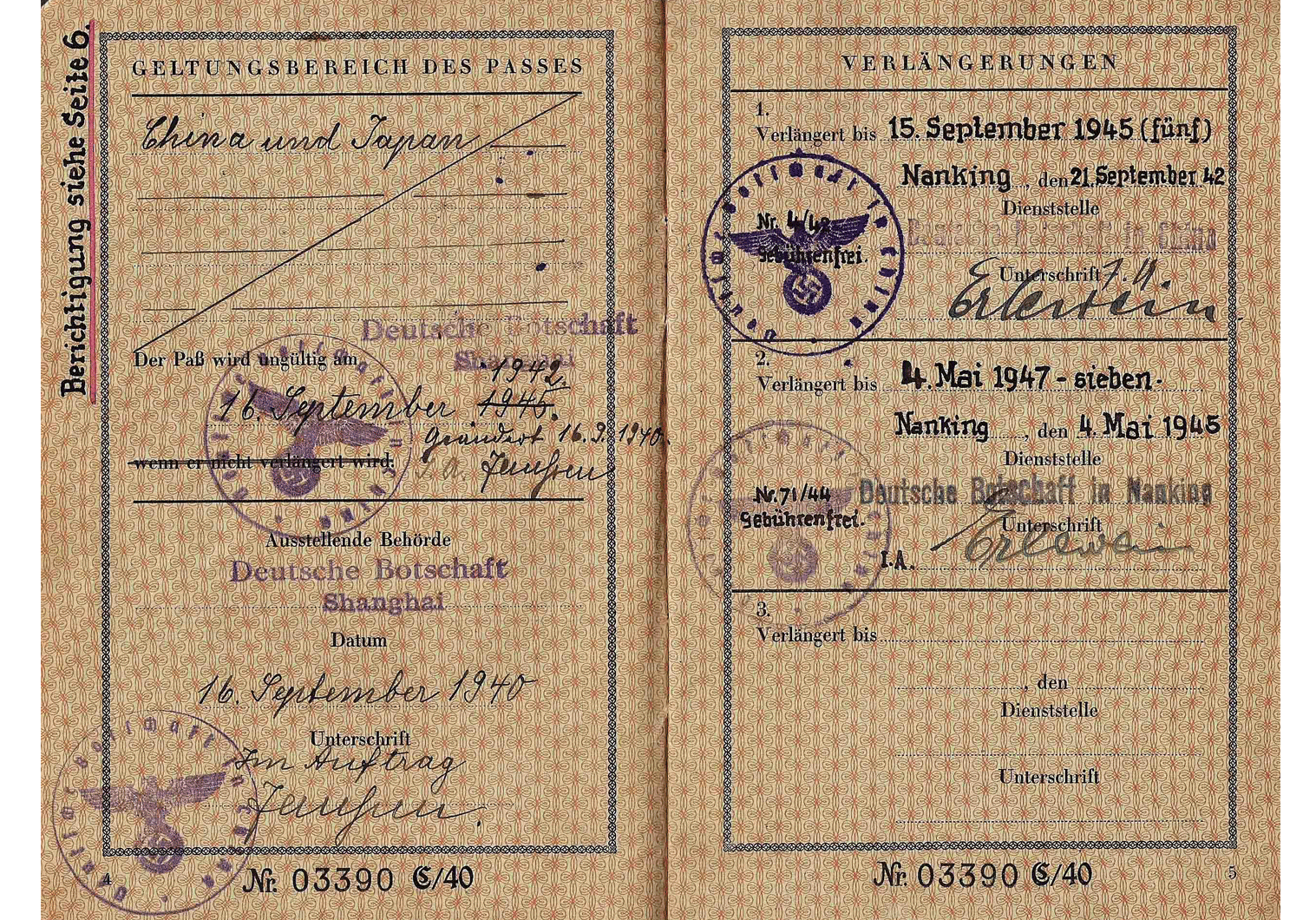

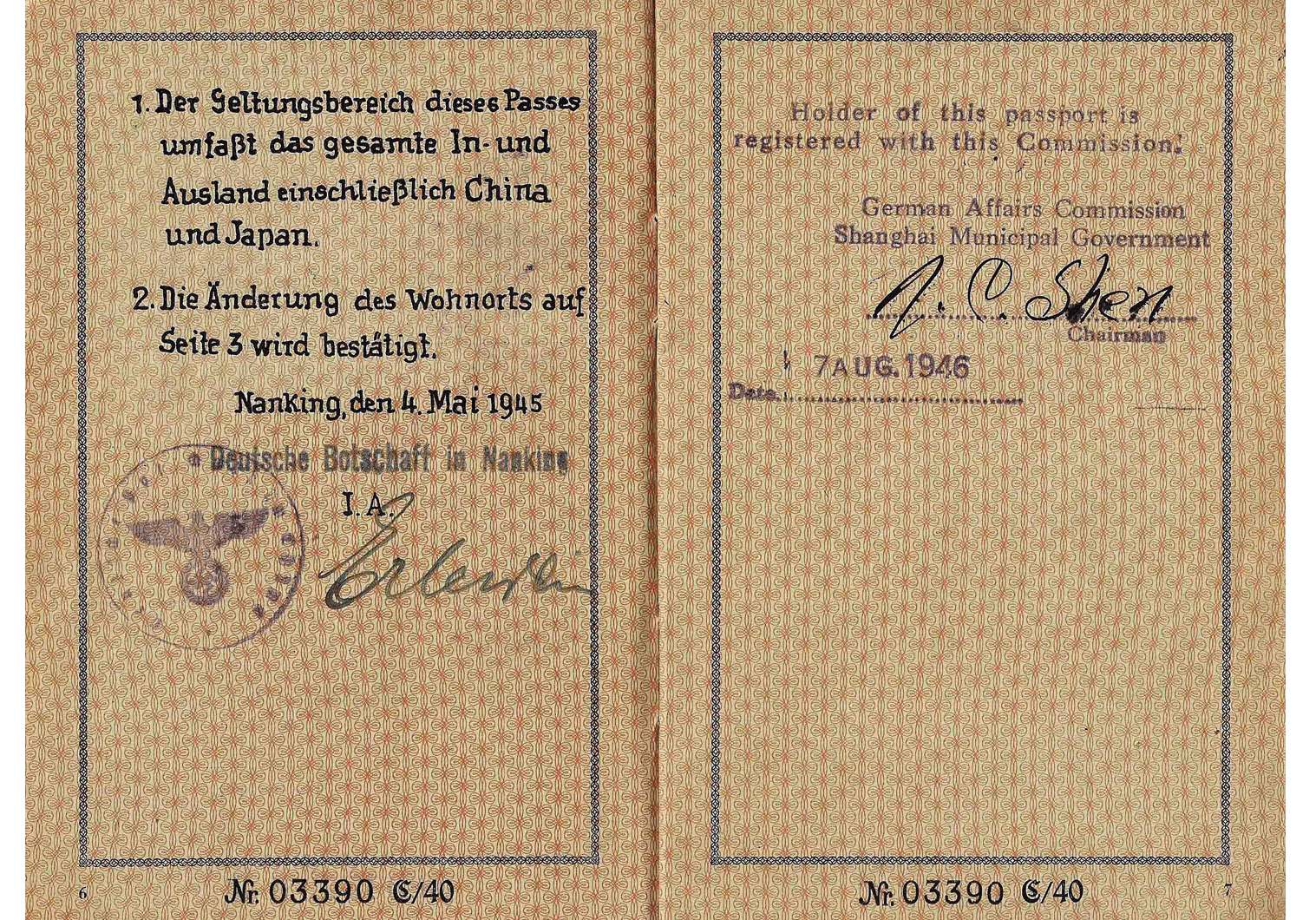

The 2nd document numbered 2/40 was issued to 18 year old Kate Harcks from Hamburg on September 16th 1940 at the German consular section of their embassy in Shanghai. This passport was an official one, a DIENSTPASS, being extended several times during the war by Josef Konrad Erlewein.

Some biographical points of this official:

Before the war he was posted to Italy and Russia, later moving to China. During 1941 to 1944 he was stationed at the German embassy in Nanjing in charge of passport & citizenship matters relating to Germans in China. From 1944 was also handling economic affairs as well; and the same year his permanent posting was changed to Shanghai.

Kate’s passport was extended first in Nanjing on September 21st 1942 and again amended on May 4th of 1945 (four days before the end of the war in Europe!) to include Japan as well for passport usage, possibly a late attempt to find refuge in still “free” Japan, but as we can see on page 7 this was not the case, she remained in China after the war and even registered as a German national at the German Affairs Commission on August 7th 1946; an extensive article on this commission and German status in China after the war can be read via this link.

Going through the pages of this passport we can learn that she remained throughout the war years in Shanghai and in 1945, towards the end, she moved south to Nanjing. After the Japanese surrender in late summer of that year she was moved most likely back to Shanghai.

Holding the two Reisepasses together one cannot feel strange that the two young women, similar occupation and from the same countries, could have had such different fates: one to be liberated after her war time ordeal and the other to be incarcerated, at least temporary, then being deported back to Germany.

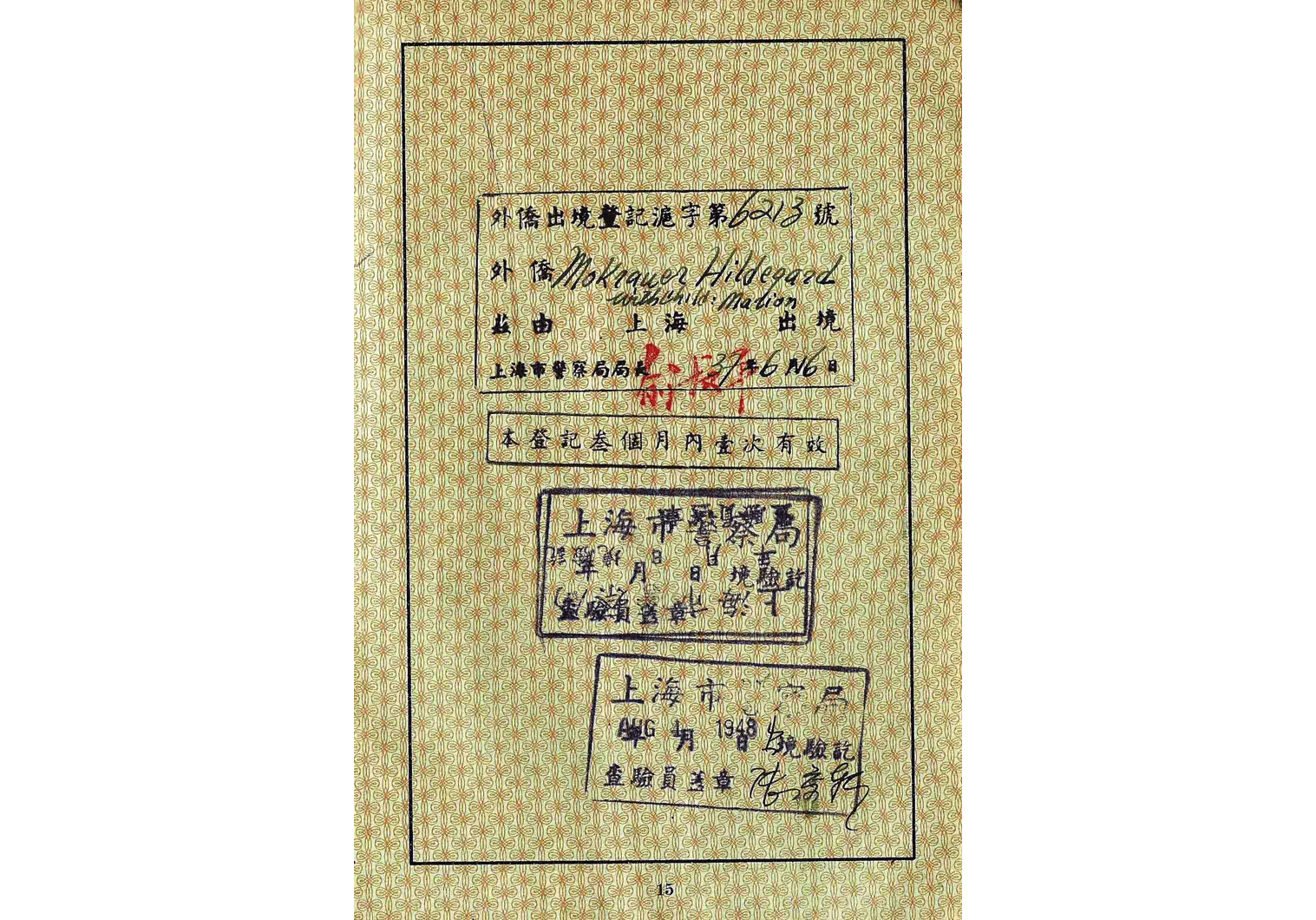

Interesting to note that Hildegard got married during or after the war and we can tell this by her name change that appears on page 15, where her Chinese exit permit from the city indicates her name is Mokrauer and travelling with child.

It is a good opportunity here for fellow collectors and historians to see two similar and yet very different passports. I leave it to you to make the comparisons.

Thank you for reading “Our Passports”.