Returning back to Harbin

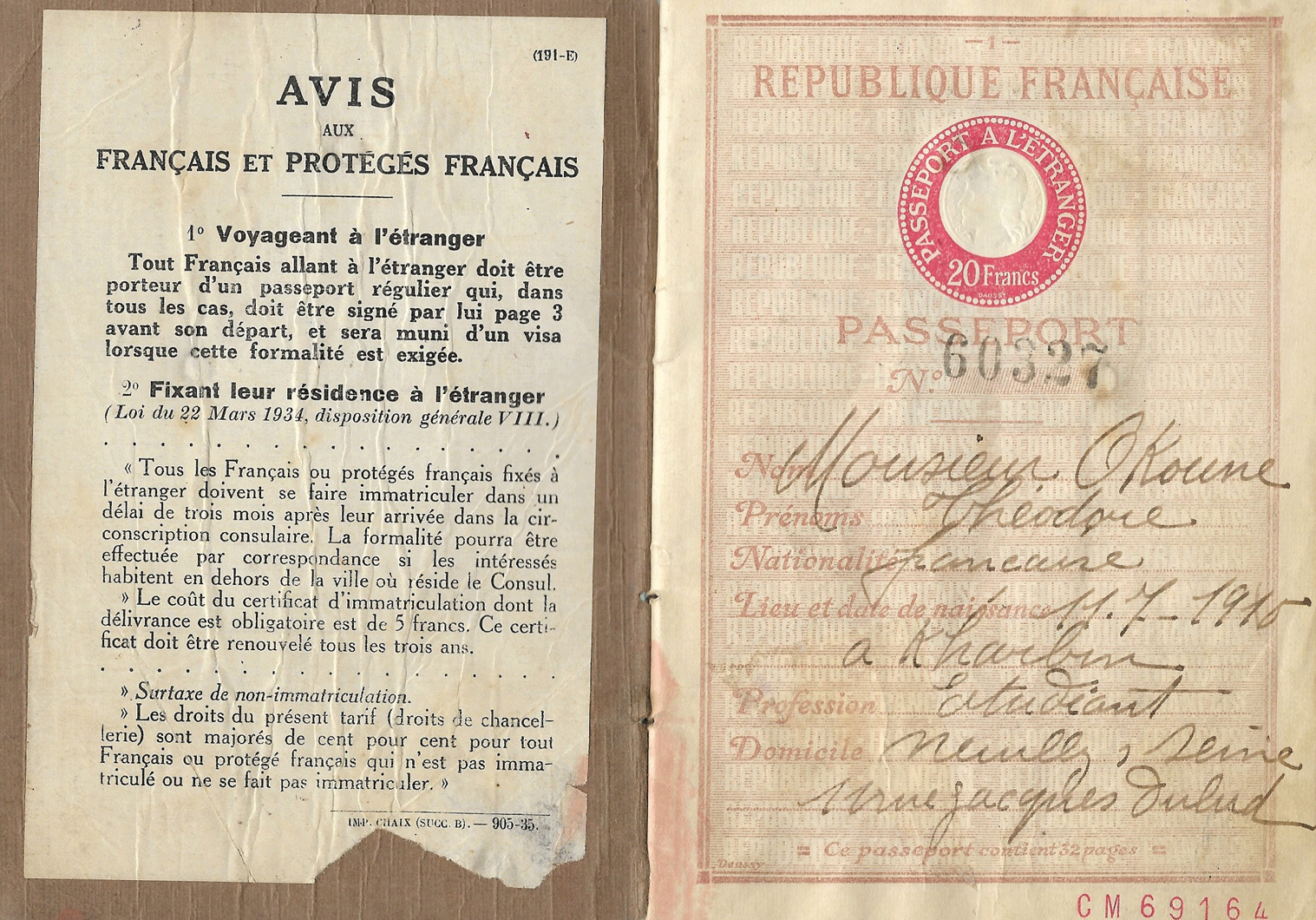

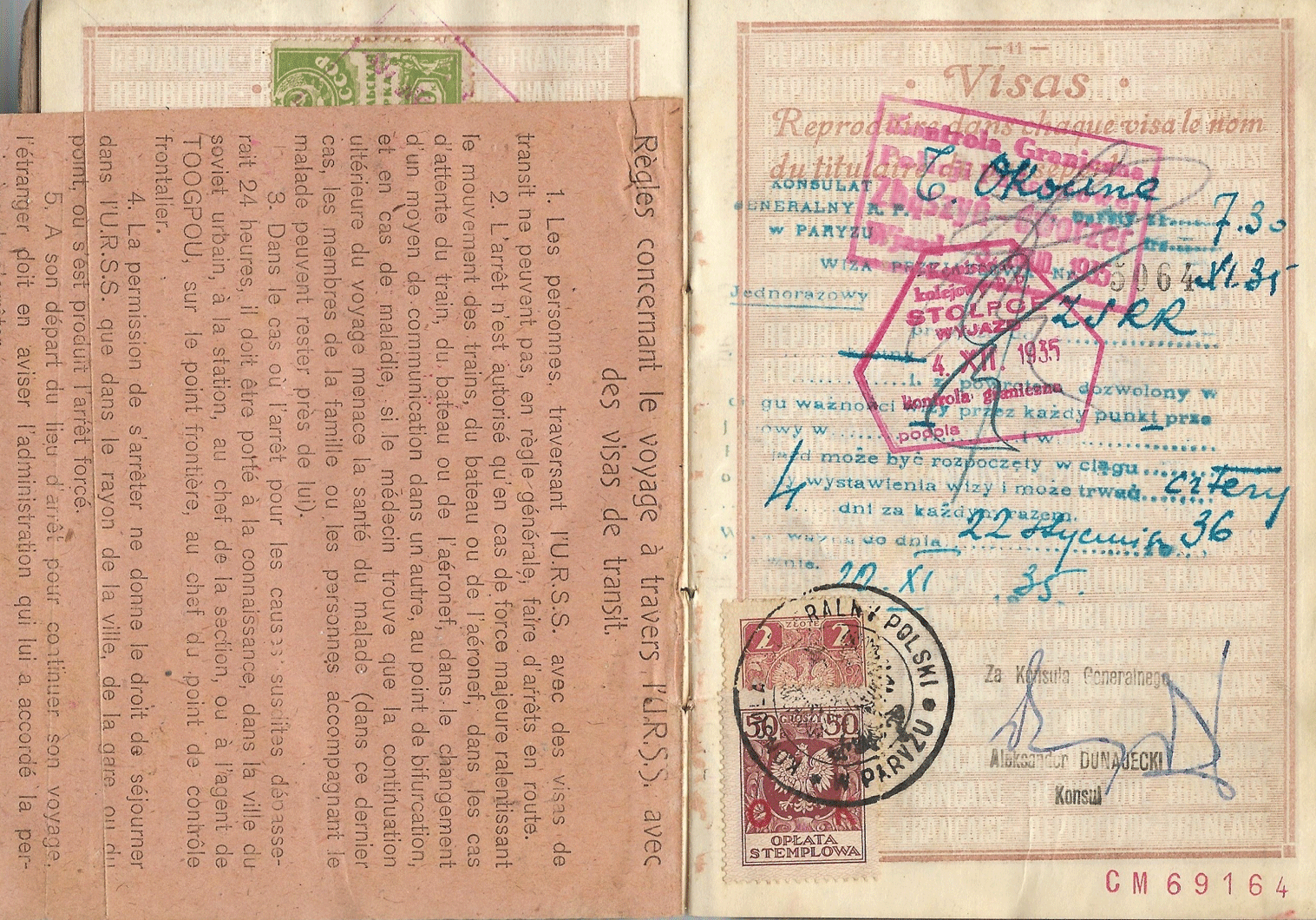

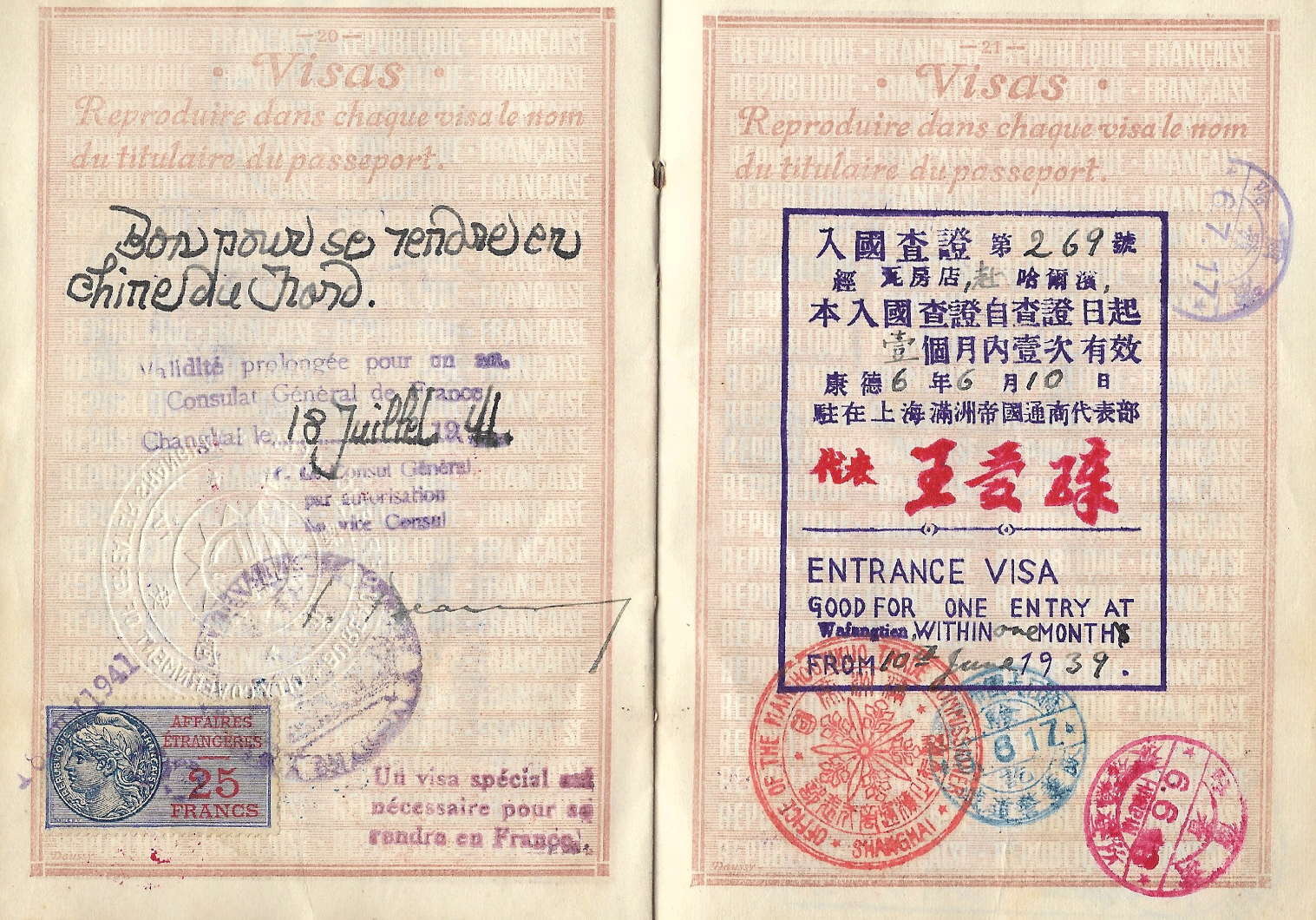

French passport used for Manchuria.

The Japanese occupation of North-Eastern China (1931 to 1945), a territory know in the mainland as Dong Bei (东北), has always interested me ever since my first visit to China over 15 years ago. September 18th 1931 was a crucial date in the history of modern China: It marks the Japanese invasion of a region known as Manchuria (a point needs to be made here: prior to the invasion, the Japanese had an enclave in the Dalian peninsula, Port Arthur, called Guan Dong Zhou Ting (关东州厅) ceded to them following the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-1905, which was a Russian naval base).

The Japanese, using it as an excuse, staged an assault on a railway track owned by them, the South Manchurian Railways, later to be known as the Mukden Incident, to invade North-Eastern China. This led to the establishment of Manchukuo. The new state began to function and run like any other country: separate banks were erected (side-by-side to existing Chinese banks), issuing of currency and postal stamps as well. Manchuria became Manchukuo after it “gained” independence on February 18th 1932, with Puyi being its head, but in fact it was controlled by the military and Japanese officials who actually ran its economy & foreign relations (from 1908 the last emperor of Imperial China was Puyi. He continued to live in Beijing, the Forbidden City, but later he moved to Tianjin, to a Japanese concession, from 1925-1931 (after being expelled from the former). He was declared emperor of the Manchurian Empire in 1934 and his “reign” lasted until 1945, the year Manchuria was liberated by the Red Army).

The League of Nations received the Chinese official protested printed report, printed by the Foreign Ministry press at Nanjing, in 1932. Detailed accounts of Japanese actions were included, covering many subjects and issues following the invasion and its effect on the local population, and this lead to the ultimate decision by the League of Nations (after accepting the Lytton Report) to reject Japans claims and explanations and to take China’s side on the matter. Japan withdrew its membership from the League of Nations in 1933.

In spite of the League of Nations’ approach, the new state was diplomatically recognized by the following countries (according to year):

El Salvador (1934), Dominican Republic (1934), Soviet Union (1935), Italy (1937), Spain (1937), Germany (1938) and Hungary (1939); and after Pearl Harbor by the following: Slovakia (1940), Vichy France (1940), Romania (1940), Bulgaria (1941), Finland (1941), Denmark (1941), Croatia (1941), Thailand ( 1941) and the Philippines (1943).

(Other nations opened diplomatic offices in Manchuria, for example Estonia, with its consulate in Harbin issuing passports to its citizen living there).

Functioning like a normal country, with foreign representation in Harbin, Manchukuo also opened consulates abroad. We can find German passports with Manchurian transit visas as well inside of them, being issued in Berlin, Hamburg and other large cities.

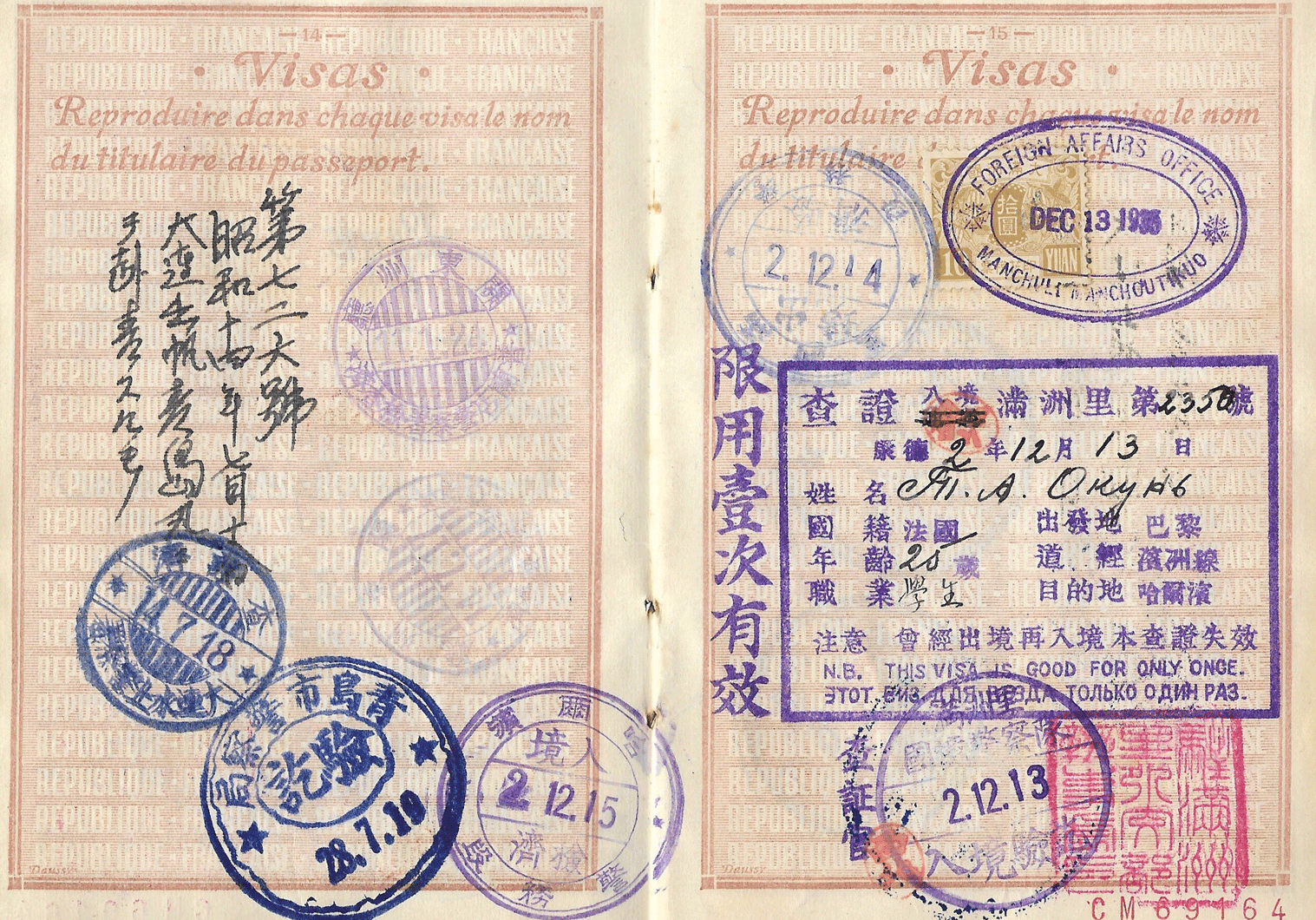

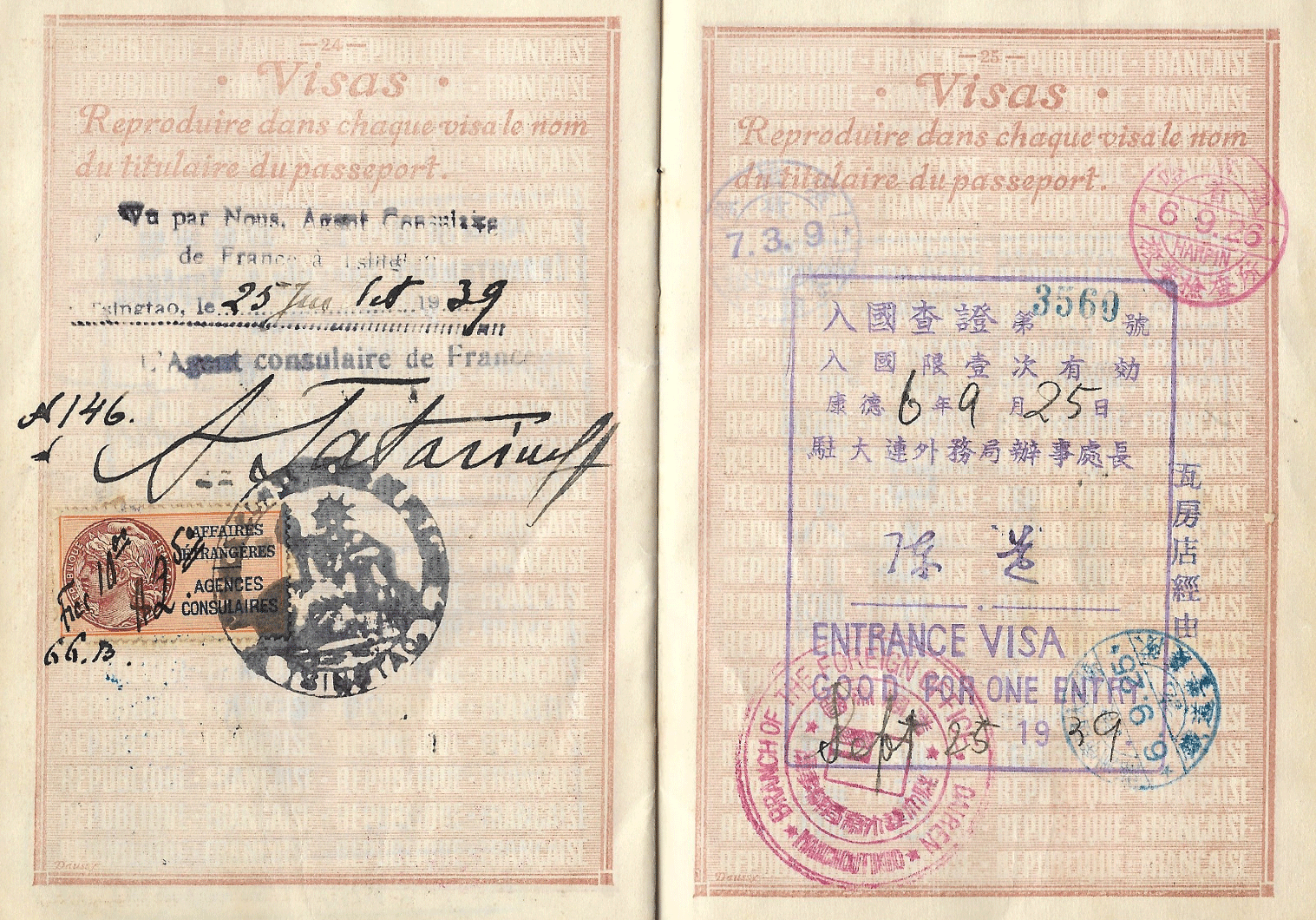

In addition, the Manchurian FM also had offices on its borders, either up north, close to the Soviet Union, or in the southern port cities, where entrance and exit was permitted as well for those who did not or could not obtain visas in advance. For example, we can locate entrance visas from Manzhouli (满洲里), Dalian (大连), Shan Hai Guan (山海关) and Wa Fang Dian (瓦房店) in the south. An important Manchurian diplomatic representation can also be located further south, in the Chinese port city of Shanghai: at first, this was an “ Office of the Manchukuo Trade Commissioner” – Beijing too had this type of representation – but these changed to official general-consulates after 1939, once full scale war and invasion of China commenced and there was no actual real need for taking into consideration international reaction or concern (on page 21 we can find a visa issued by the Shanghai trade commissioner who was a native: Wang Qingzhang 王庆璋, born on June 12th 1894 who arrived in the city in early 1939. Later posts were Postmaster General to Manchuria in 1942 and Manchuria’s highest representative in the Philippines in 1944).

Now back to the passport in this article:

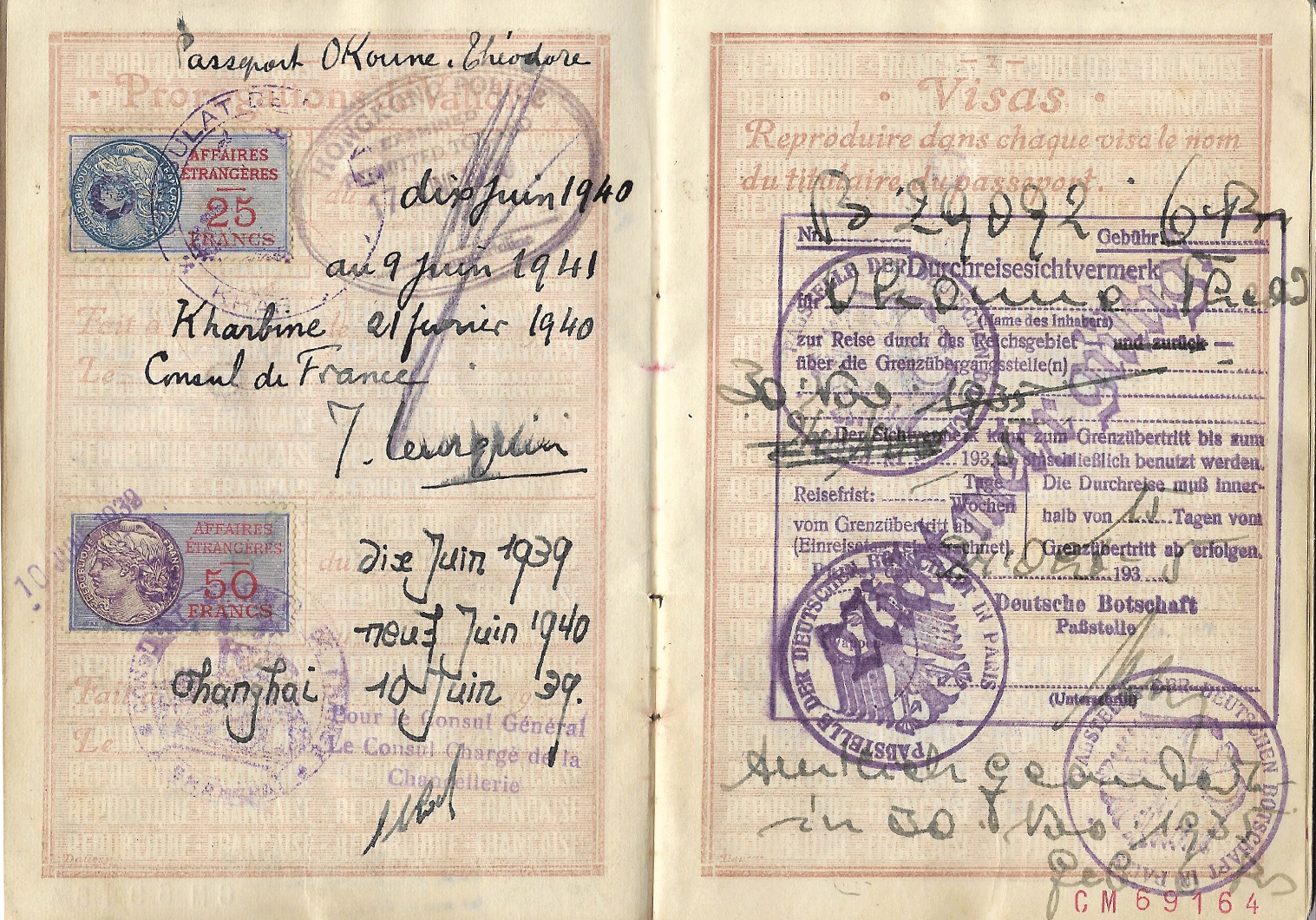

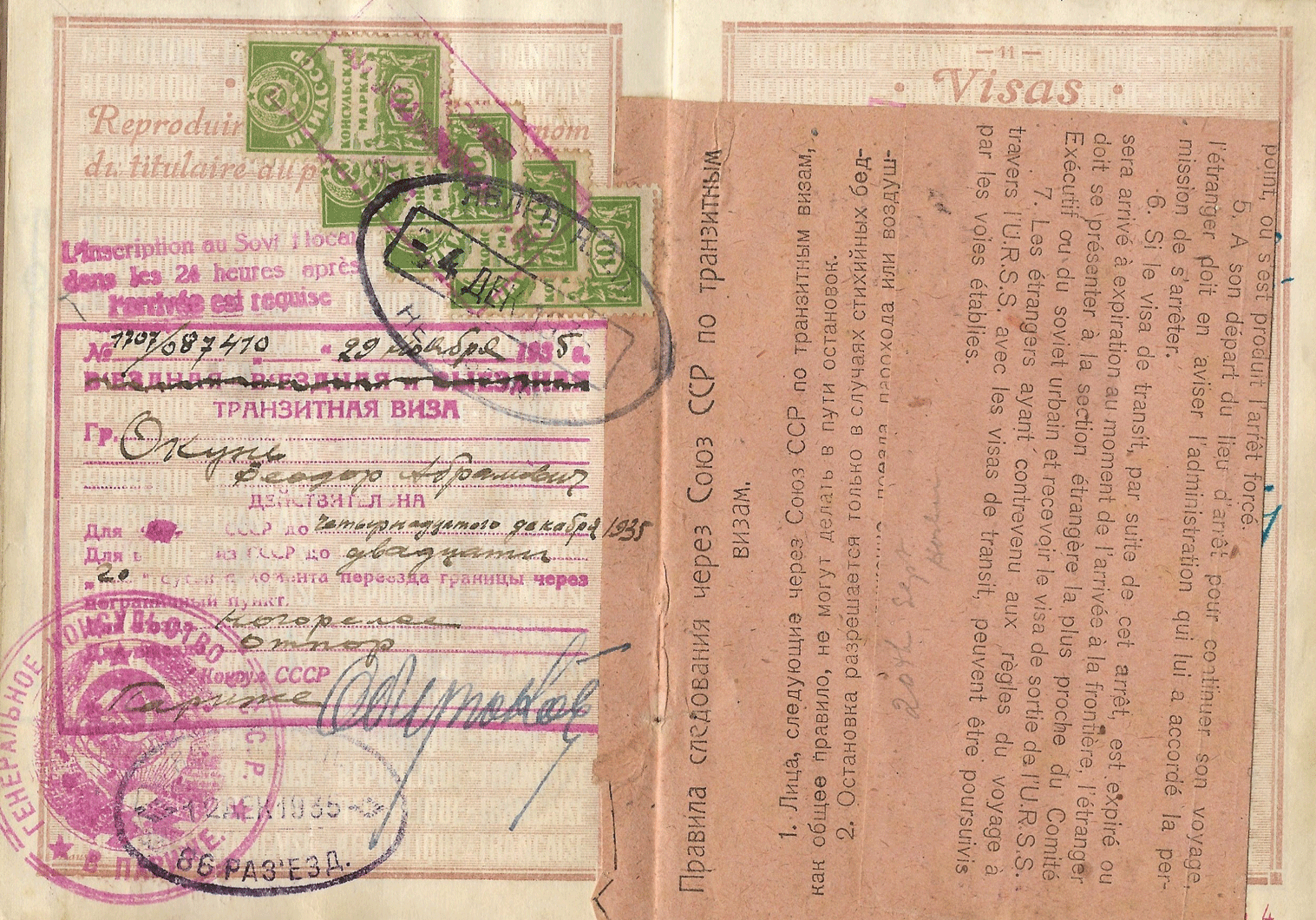

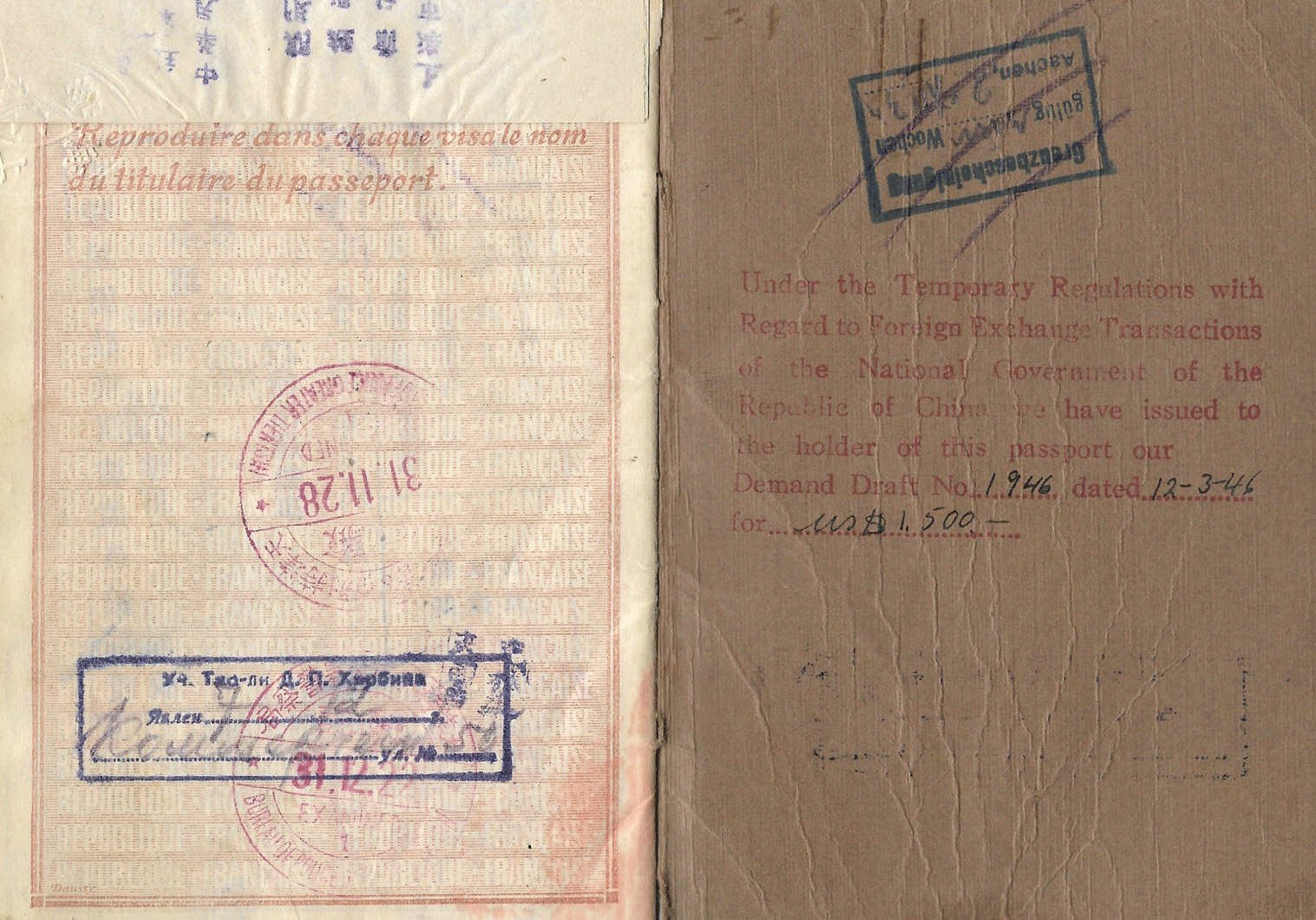

French passport No. 60327 was issued to Theodore Okoune aged 20 who was born in Harbin. The passport was issued on October 18th 1935 in Paris, and most likely issued to him for his return back to China (occupied) – for returning back to Harbin. For this journey, Theodore applied for the following transit visas: German, Polish and Soviet, all issued by the consular departments in the French capital towards the end of the year: Exiting France on December 1st, entering Germany then crossing over into Poland 2 days later and exiting the next day into the Soviet Union via the joint border crossing at Stołpce (now a city in Belorussia). Theodore travelled via rail to the Chinese-Soviet border town of Manzhouli (满洲里) where he obtained the Manchurian entrance-visa from the FM bureaus in the city on December 13th, right after arriving (Russian exit date is indicated for a day earlier).

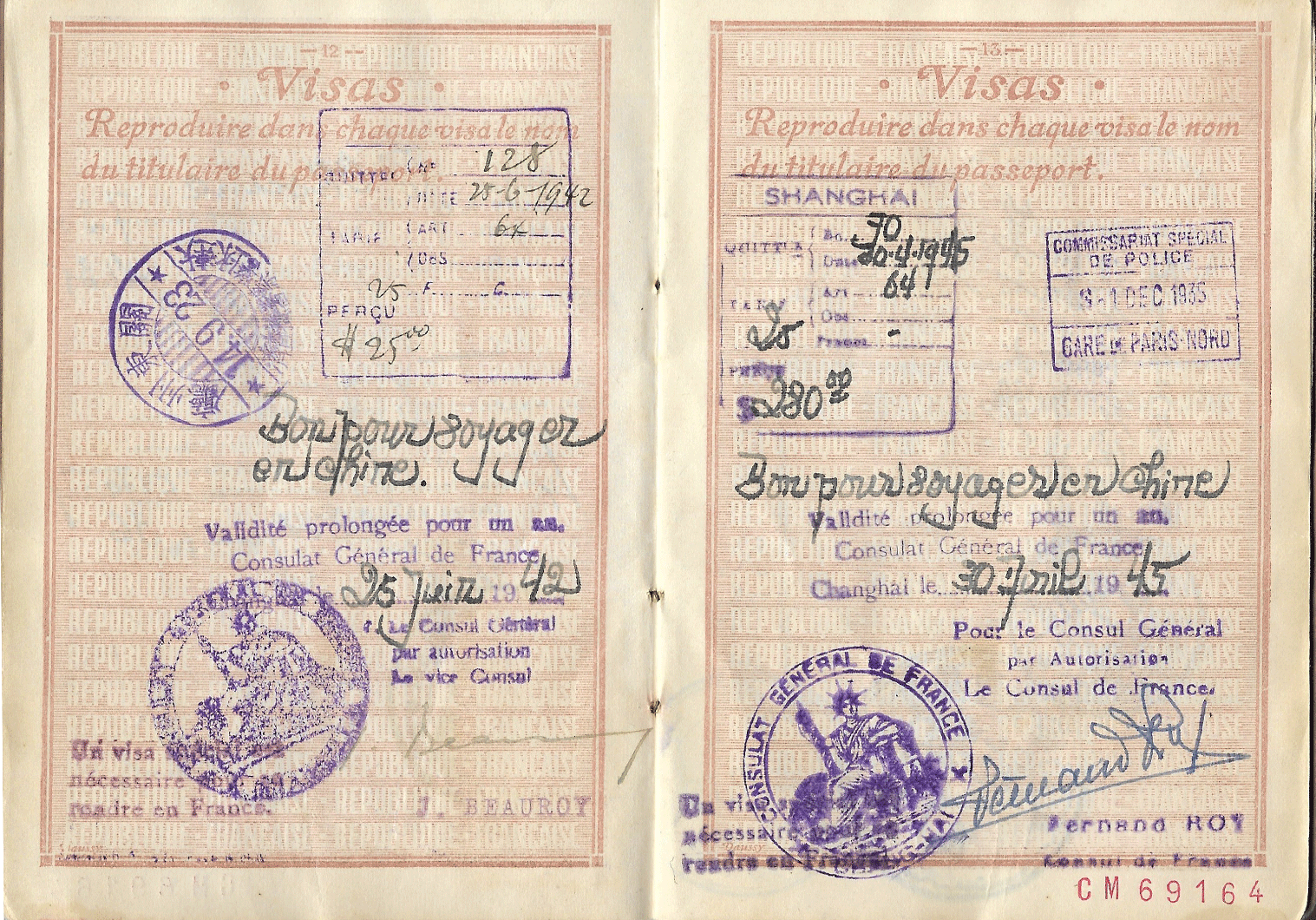

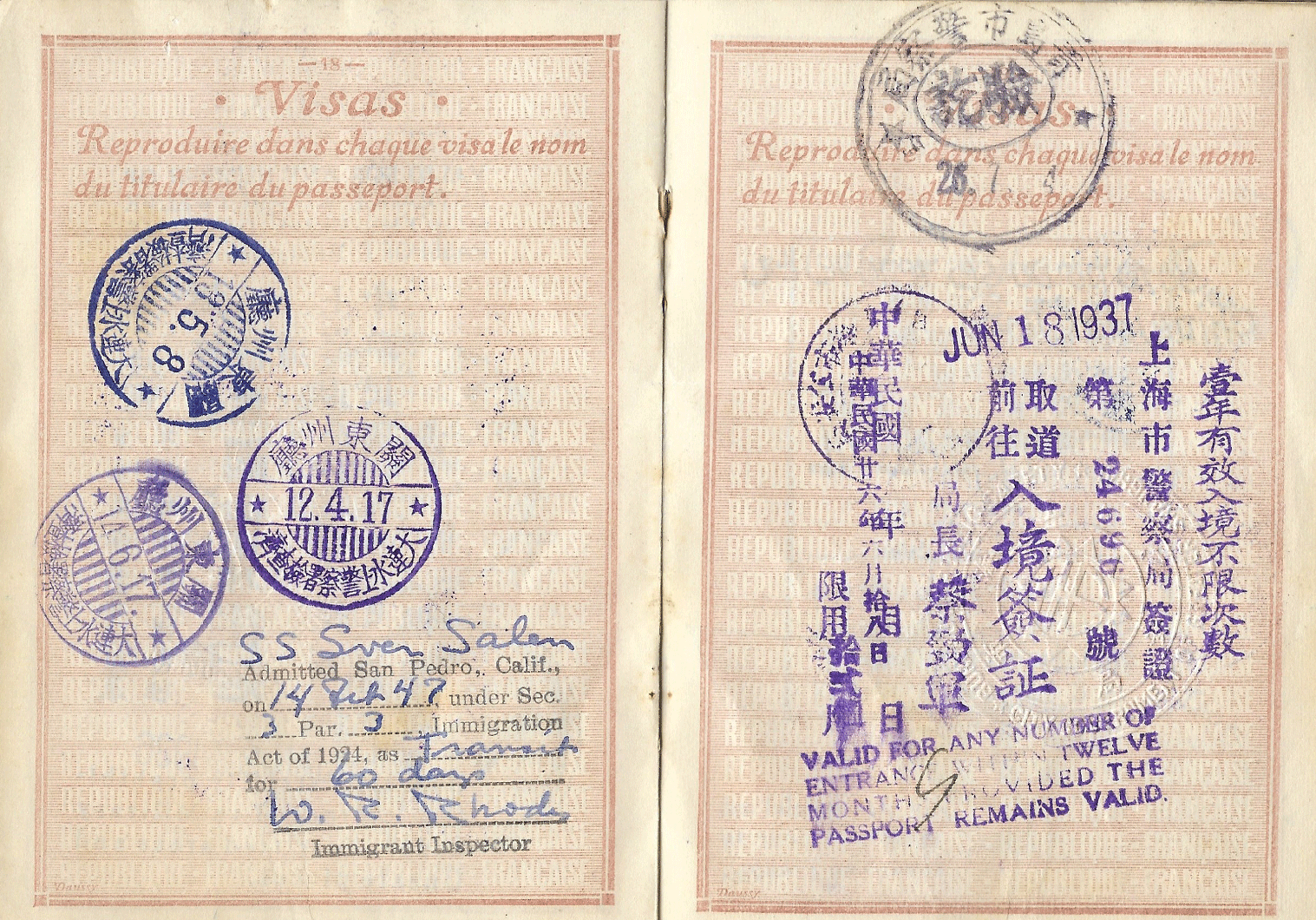

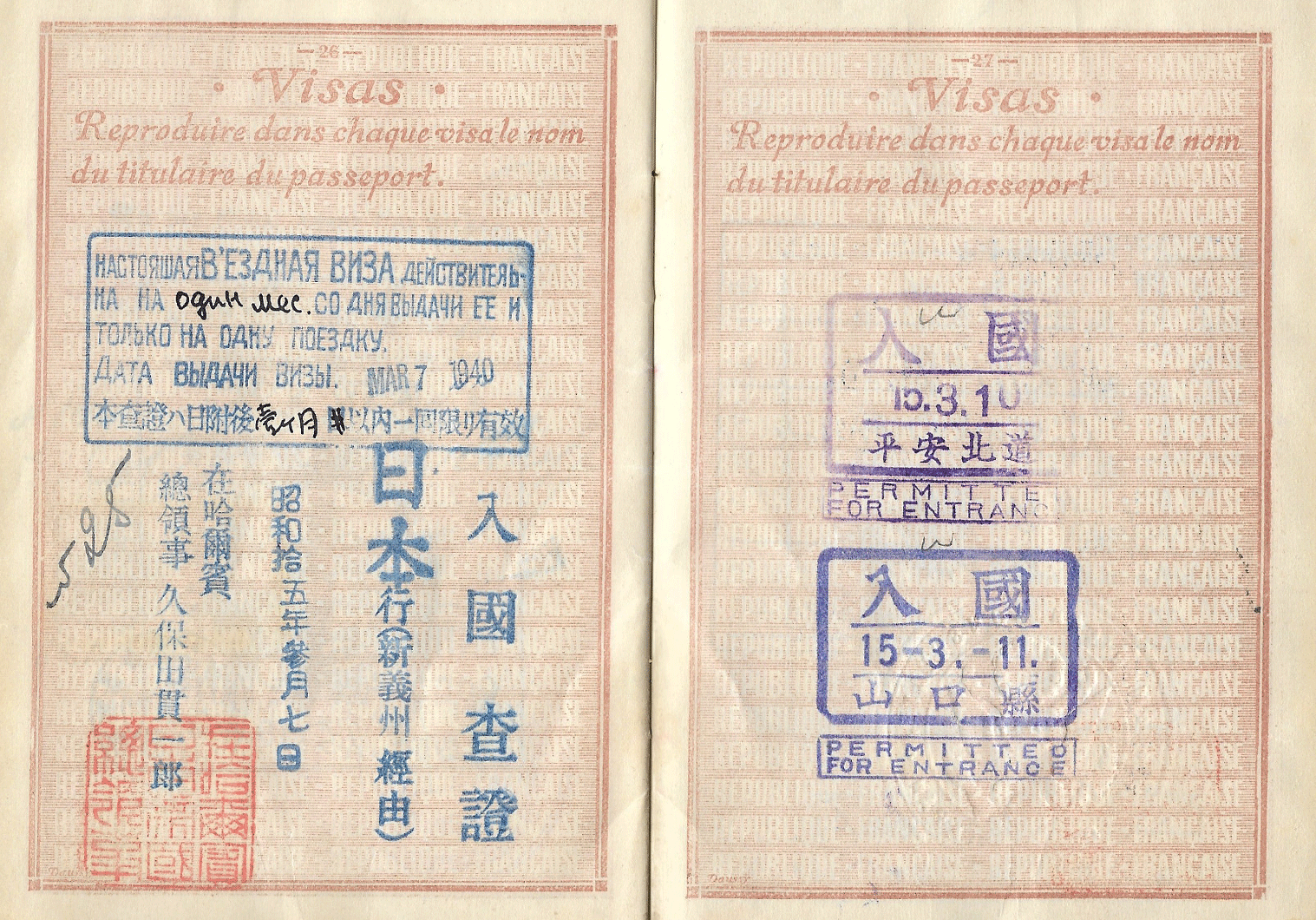

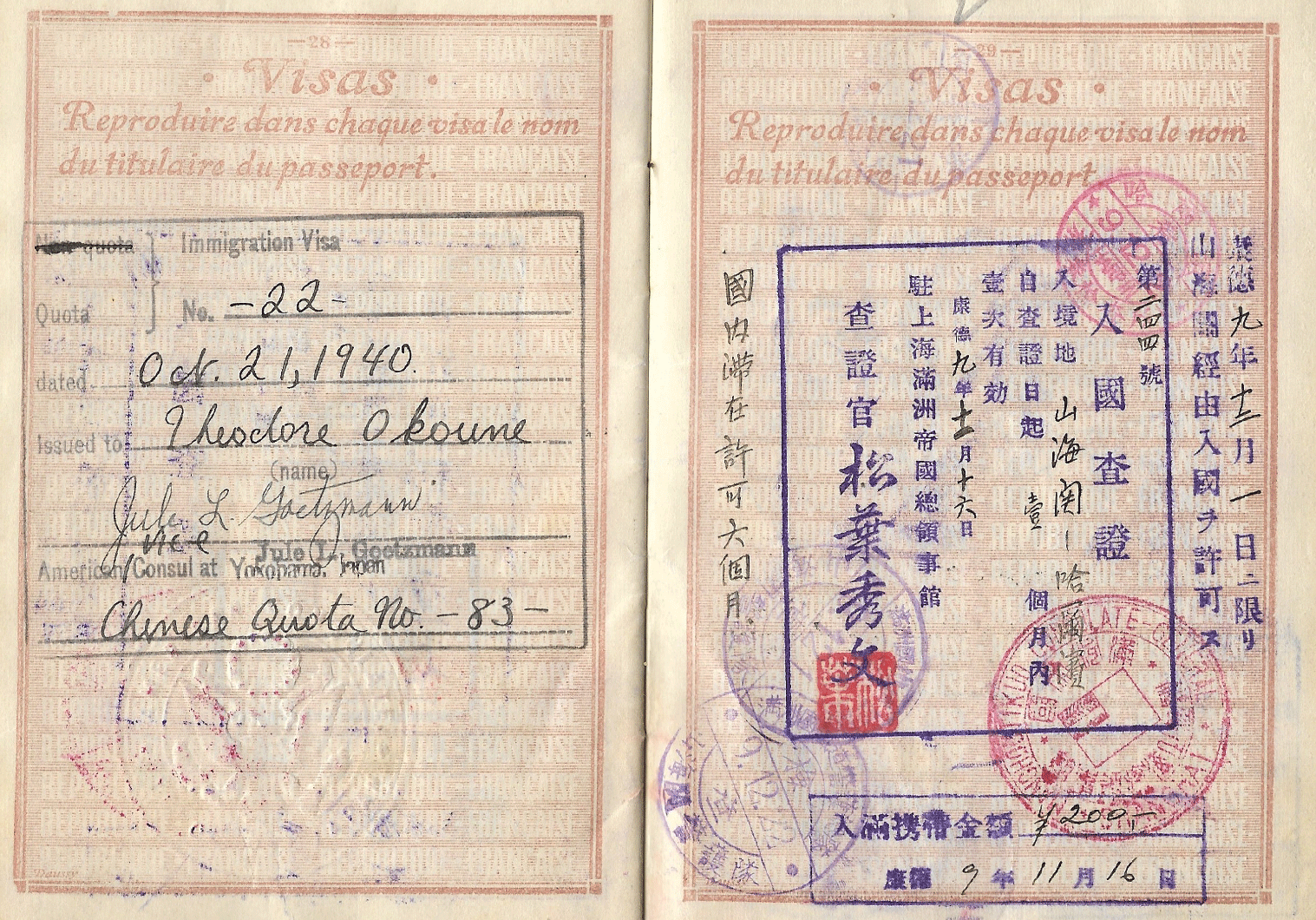

From this point onwards, his stay in the Far East becomes very very interesting: apparently he opted to remain in occupied China after the fall of France even though he obtained a US immigration visa no. 22 (Chinese quota no. 83) on October 21st 1940, from the US consulate in Yokohama (he was living in Japan for close to a year, arriving there on March 11th 1940 and leaving back to occupied China, for Shanghai, after February of 1941 – the time he obtained a return visa form the Chinese puppet regime consulate also in the city of Yokohama).

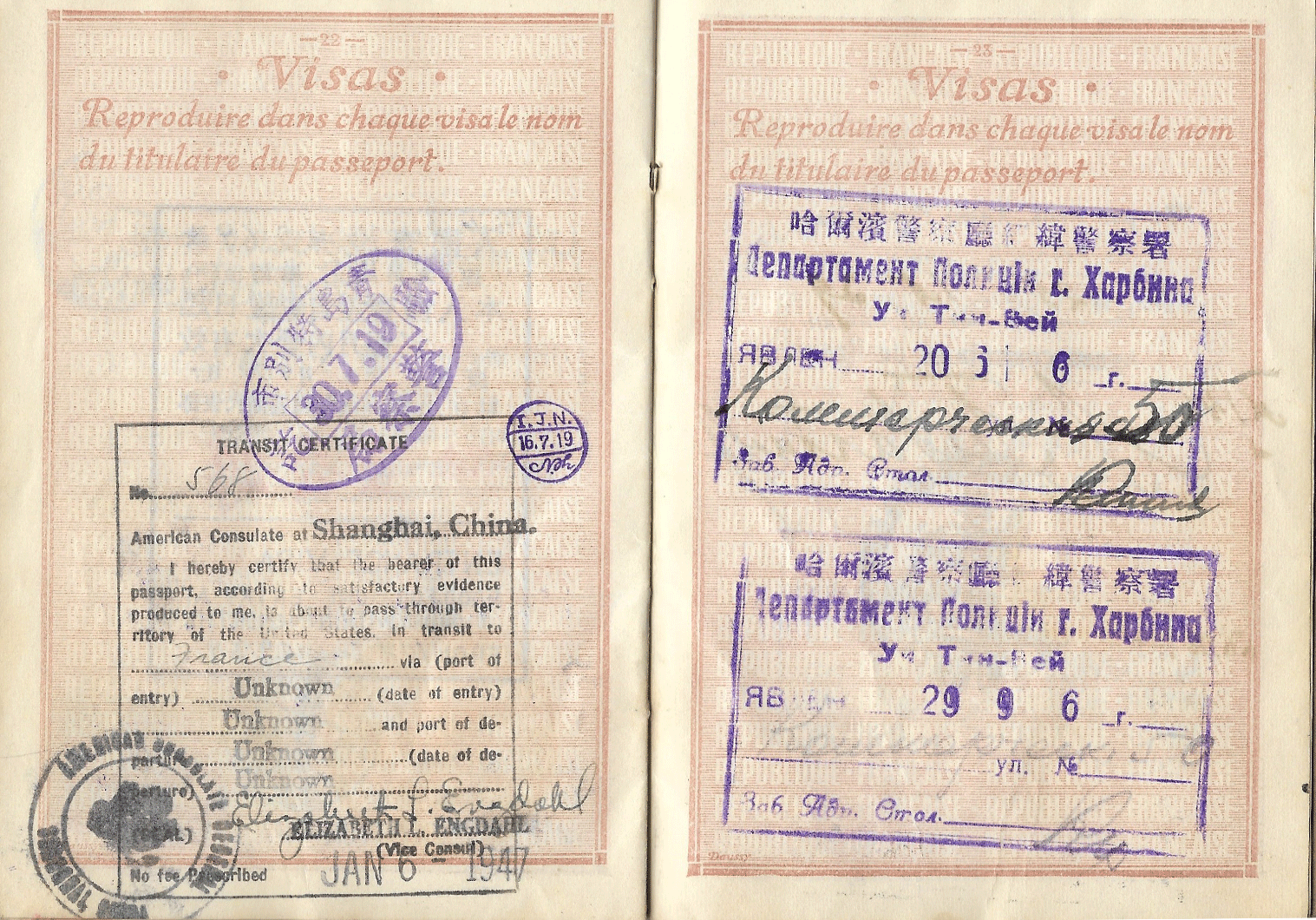

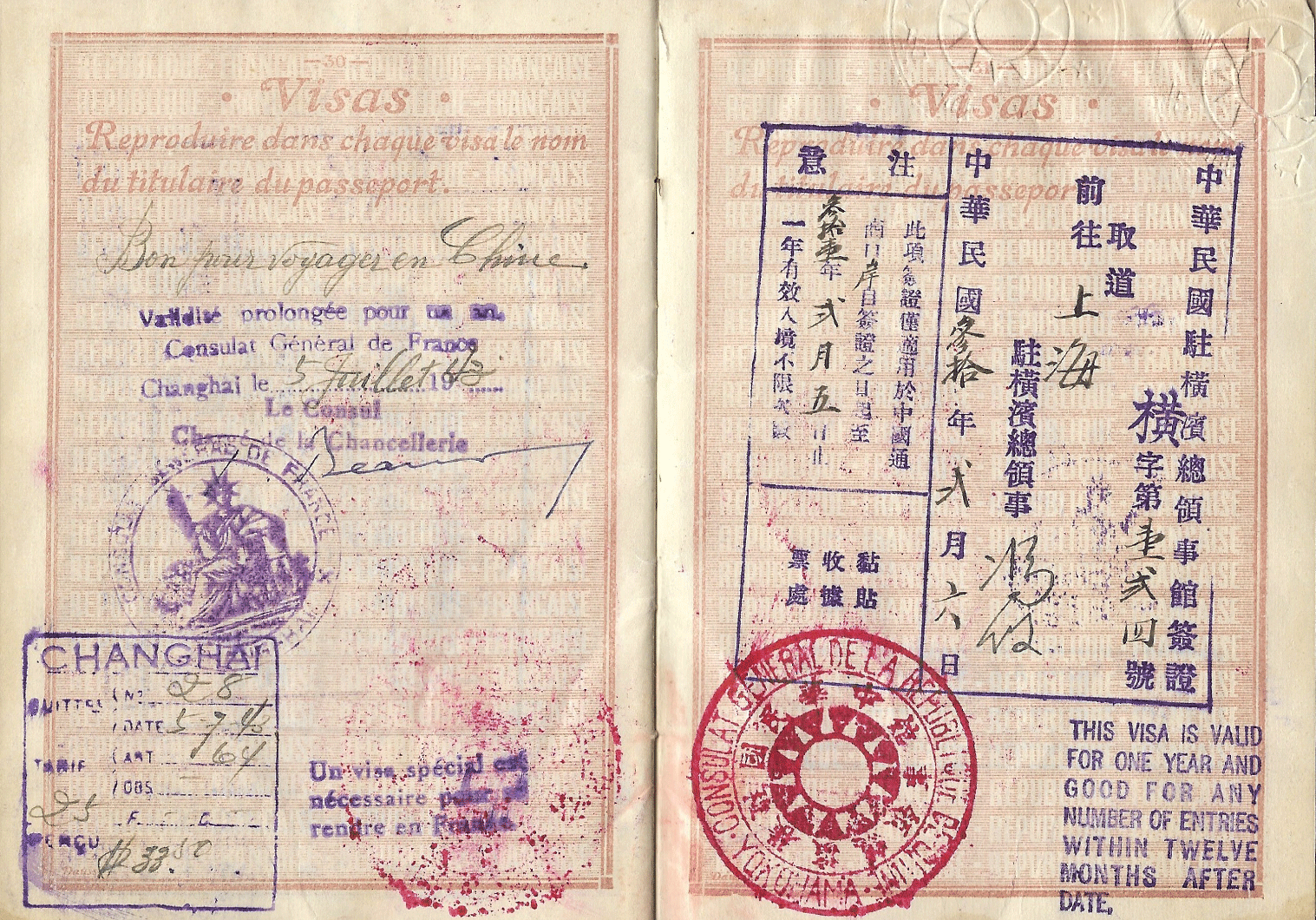

The passport has in total of 4 different Manchurian visas and entry permits, Japanese entry visa issued in 1940 at Harbin (with specific traveling instructions via rail through occupied Korea – 新义州经由). Interesting additional point is the likelihood that the holder was, temporarily, on the French Vichy side because of the Vichy consular issued passport extensions from the consulate in Shanghai (1941-43 & 1945) – this could maybe also explain why he was not interned (and not being a citizen of Free France).

On page 26 we can locate an attractive Japanese consular visa from Harbin, issued by consul-general 久保田贯一郎 (Kubota Kanichiro): he would attend a committee of the Manchurian Nationalities that was held in the Soviet Union at Chita (this was also transit point out of the USSR on the way to Japan or occupied Korea during the 1930’s and up to 1945). His last war-time post was consul-general at Saigon in 1944.

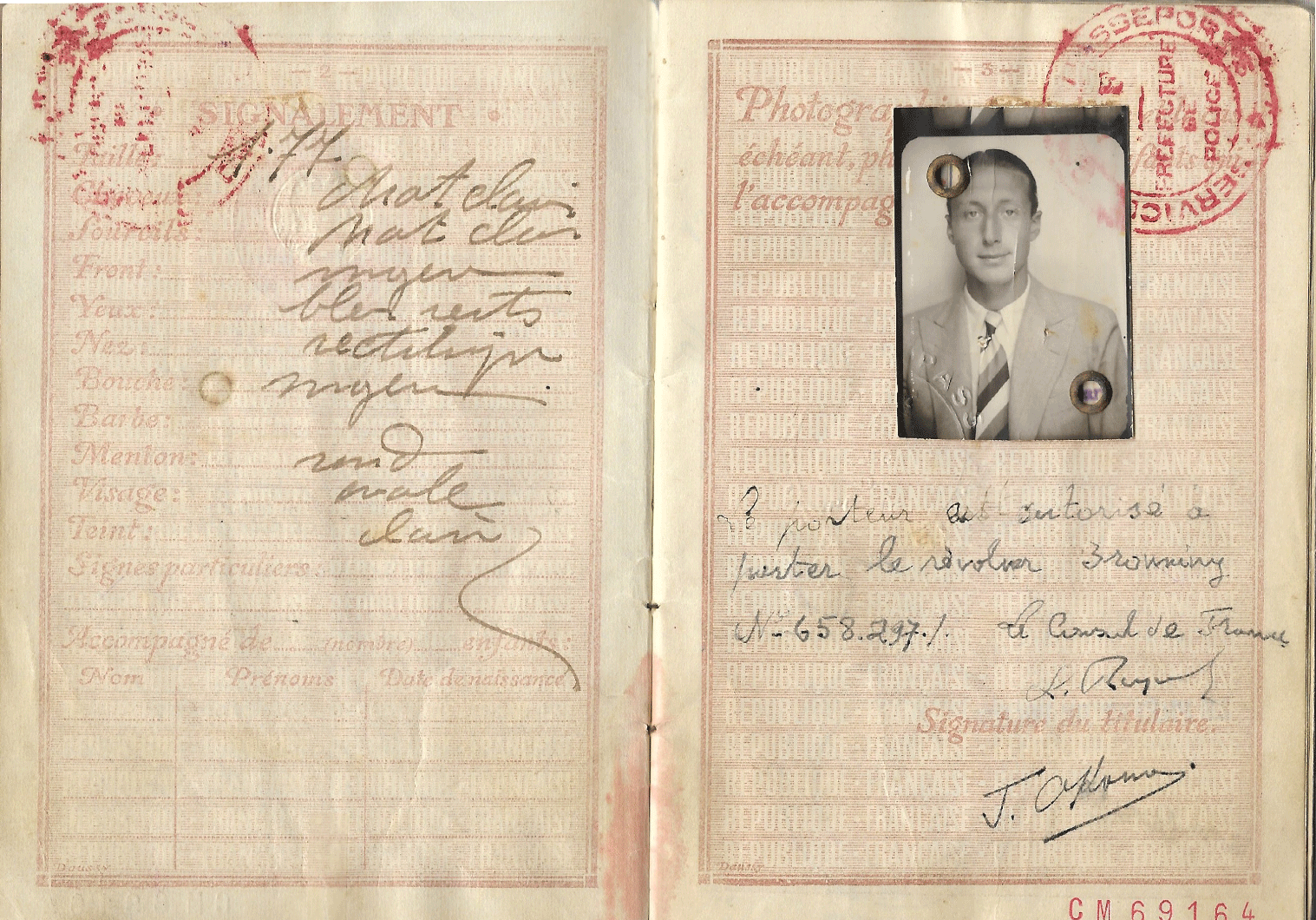

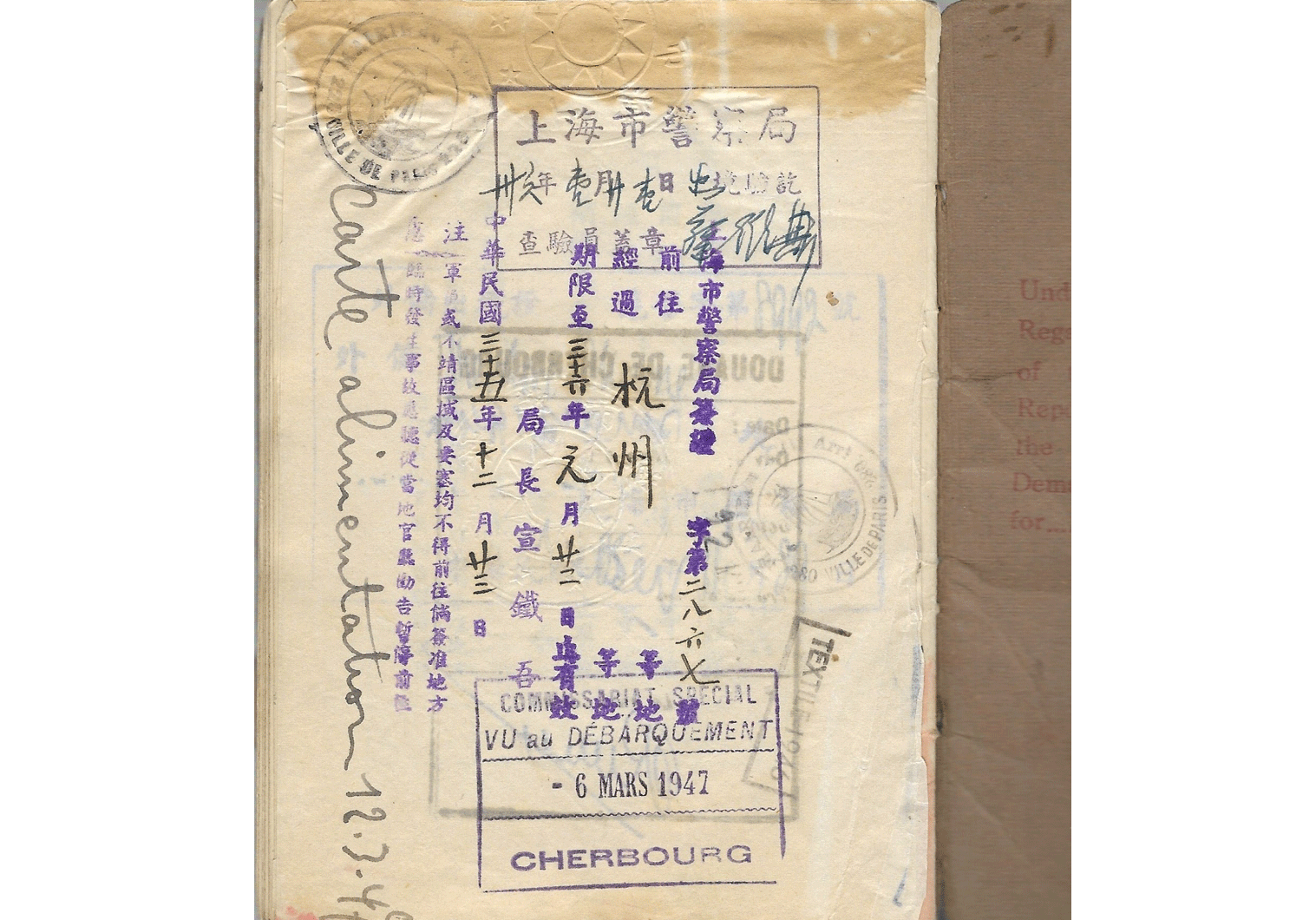

We can also locate post-war Chinese exit permits from Shanghai dating from 1946-47 and US transit visa issued in early 1947 for returning back to France on March 6th at Cherbourg (he was issued a US browning pistol (no. 658297) most likely after the arrival of US troops to the city in late 1945 – it is hand inscribed as such on page 3, beneath his photo – though it is indicated as being done so by the French consul, lacking a consular stamp would make me suspect it could have been added by him “himself”).

Important addition: the small applied Japanese chop on page 22 is significant because it is the ONLY one to date that I have located inside a passport. Apparently it is an Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) marking of inspection dating the same day he left Qingdao, leaving earlier first from Shanghai, possibly to southern Manchuria, and instead of going through a civilian entry point he must have, and this is an assumption here, gone through a NAVAL inspection point once disembarking from the vessel that took him from the Chinese port.

Have added images of this fascinating passport with war-time Axis issued visas.

Thank you for reading “Our Passports”.