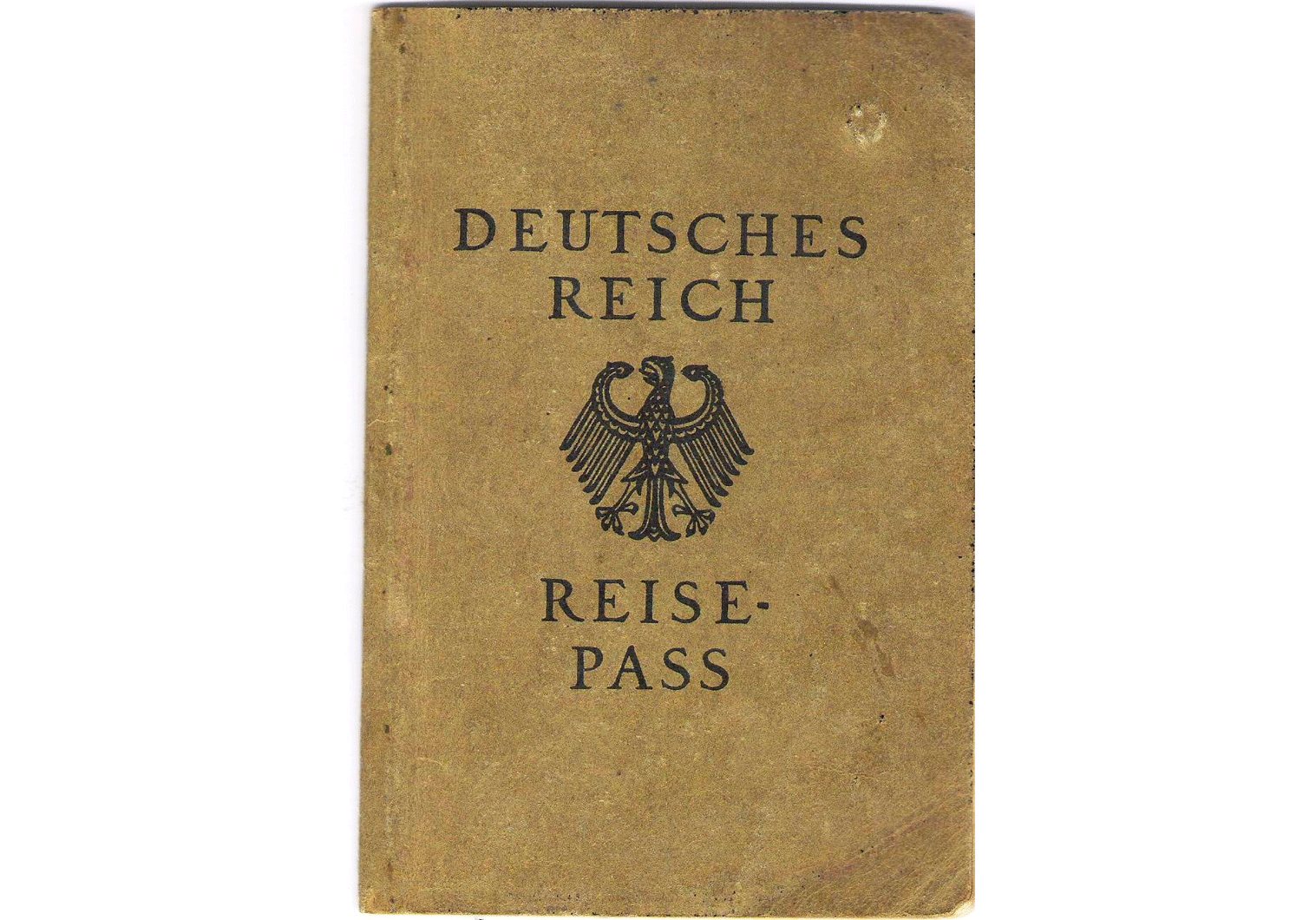

Late Weimar Republic passport

Used to immigrate to the Mandate in 1933.

1932 was the last year of the democratic republic of pre-war Germany.

The Weimar Republic that came to be after the end of the First World War, be it for the right or wrong reasons, was the most liberal and open in the country’s history. All people, Jews and non-Jews, could participate in nearly every form of activity in the country: political, cultural, religious and more. The open atmosphere that was beacon for all would be extinguished, the candle of hope and equality would burn out, and with it gone, darkness and terror would sweep the country for 12 years, and lead it to the abyss and then into devastation and darkness.

This was the end of an era, and last months of the republic, a dying republic, which was swept by political turmoil and chaos, violence and terror. The events of WWI mixed with the economic depression that came at the end of the 1920’s all would mix into a toxic cocktail that erupted in all its fury during those last months, prior to the events, those fateful events that would come at the beginning of the coming year.

January 1933 was the firing shot that would push the country to the edge of the abyss, every moment closer and closer to the inevitable outcome at the end: total animalization, first of its moral code and conduct, then to the actual physical destruction of its citizens.

After Adolf Hitler came to power, not many saw the writing on the wall. The violence that was perpetrated upon the Jewish population was seen as a temporary effect of the seizure of power, something that could settle down or be tamed. Many did not grasp the events or the seriousness of the Nazi party and the path it was willing to walk down.

But some did. Some individuals understood where the wind was blowing and began to take measures to leave, escape their beloved country, when it was still possible to do so with their property or their life savings. During the beginning, before laws were implemented and the Jews were forbidden to leave with their assets, it was relatively possible to do so, to travel abroad and start fresh new life far away from the developing events.

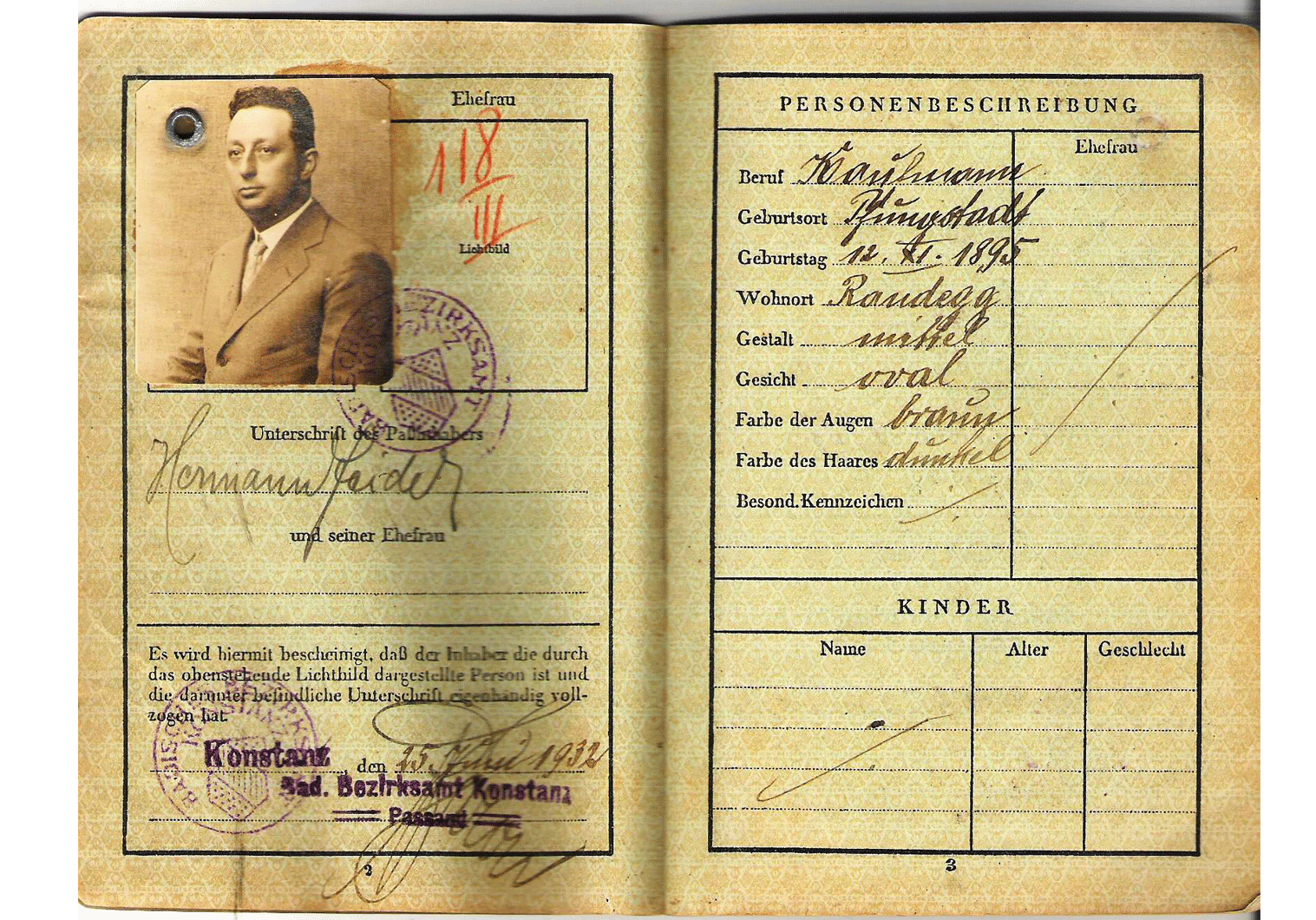

Hermann Feidel, aged 36, seems to have understood clearly what was happening by early 1933.

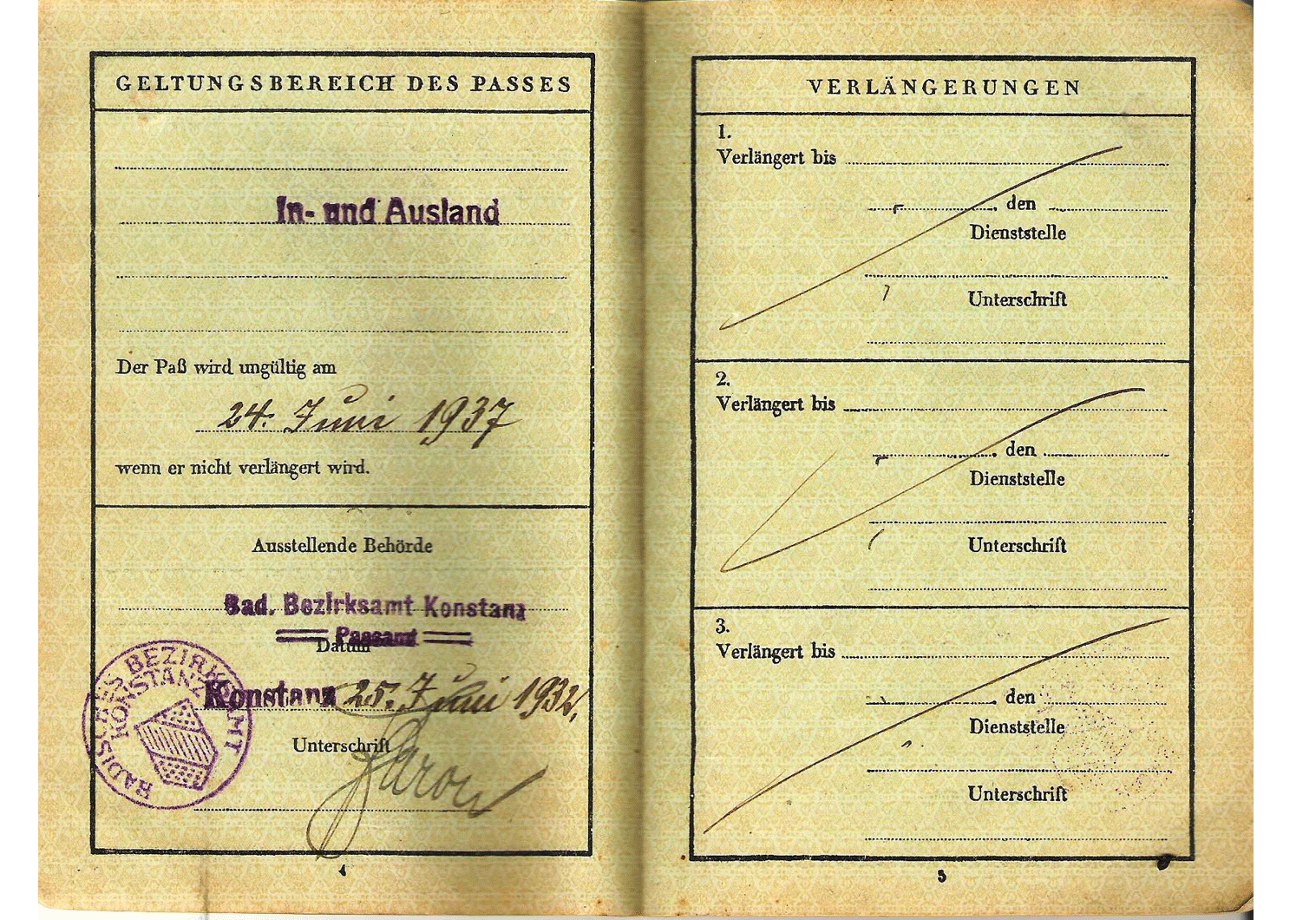

German passport number F24 was issued at Konstanz on June 25th 1932, but was not put to use. It was only close to a year later, that it was used to leave Germany.

That year was the beginning of mass immigration and the flowing of countries with refuges, mainly Jewish, that were beginning, though slowly, to leave and try finding refuge in neighboring countries at first, and when it became more difficult in doing so, they tried further away, even reaching at the end far away as South America or the Far East, China.

Switzerland was an attractive location starting already at the first months of 1933: the culture and language were similar and many found it logical to try and find residence there. But as the quantity of those trying to find refuge began to get larger, a trickle that would possibly lead to a flood, the Swiss authorities began to take actions in order to curve what they saw as a threat to their culture and its citizen.

The early 1930’s saw also “internal immigration” or Binnenwanderung in German, where Jews began their departure from smaller communities within Germany itself; this was the case because racial hostilities towards the Jews were rife and stronger in smaller villages and towns, thus the Jews found refuge and “anonymity” in the larger developed bustling cities. In communities that were closer to the borders, where the locals new the ways and methods to pass more easily to neighboring countries, Jews opted also for crossing the borders rather than travelling deeper inside Germany itself. We can find cases of refugees arriving in Basle as early as 1933 (the statistics of time show that the flow of refugees out of the country began to ease towards the end of the year and by 1934 signs were showing that some were already preferring to return back home: this was a horrific outcome that the party and the authorities wanted to stop at any cost, and in order to discourage their former Jewish civilians from retuning back they began implementing a new method by which any returnee would be arrested by the Gestapo and incarcerated inside a concentration camp for “Re-education” – this was done so in 1935).

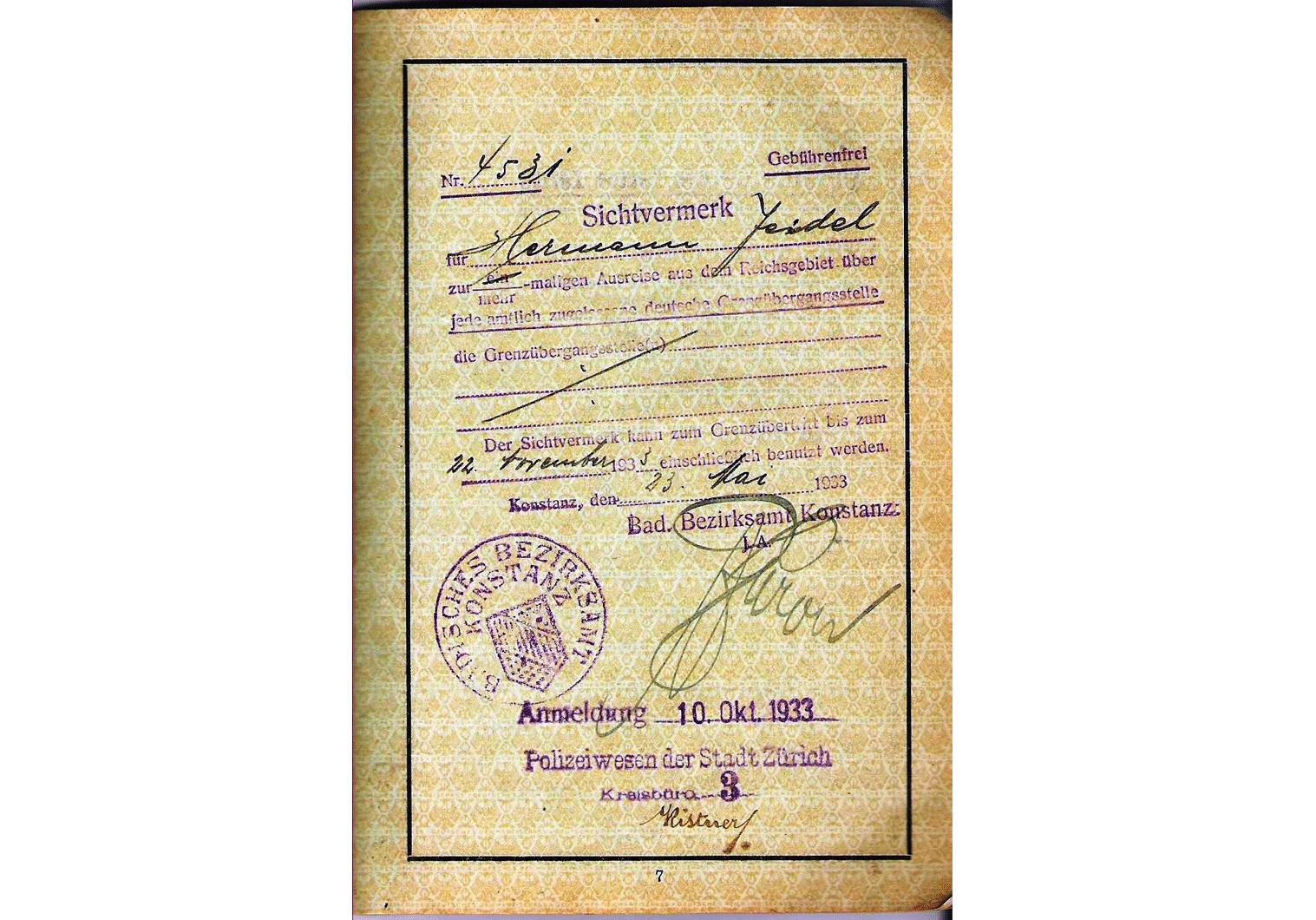

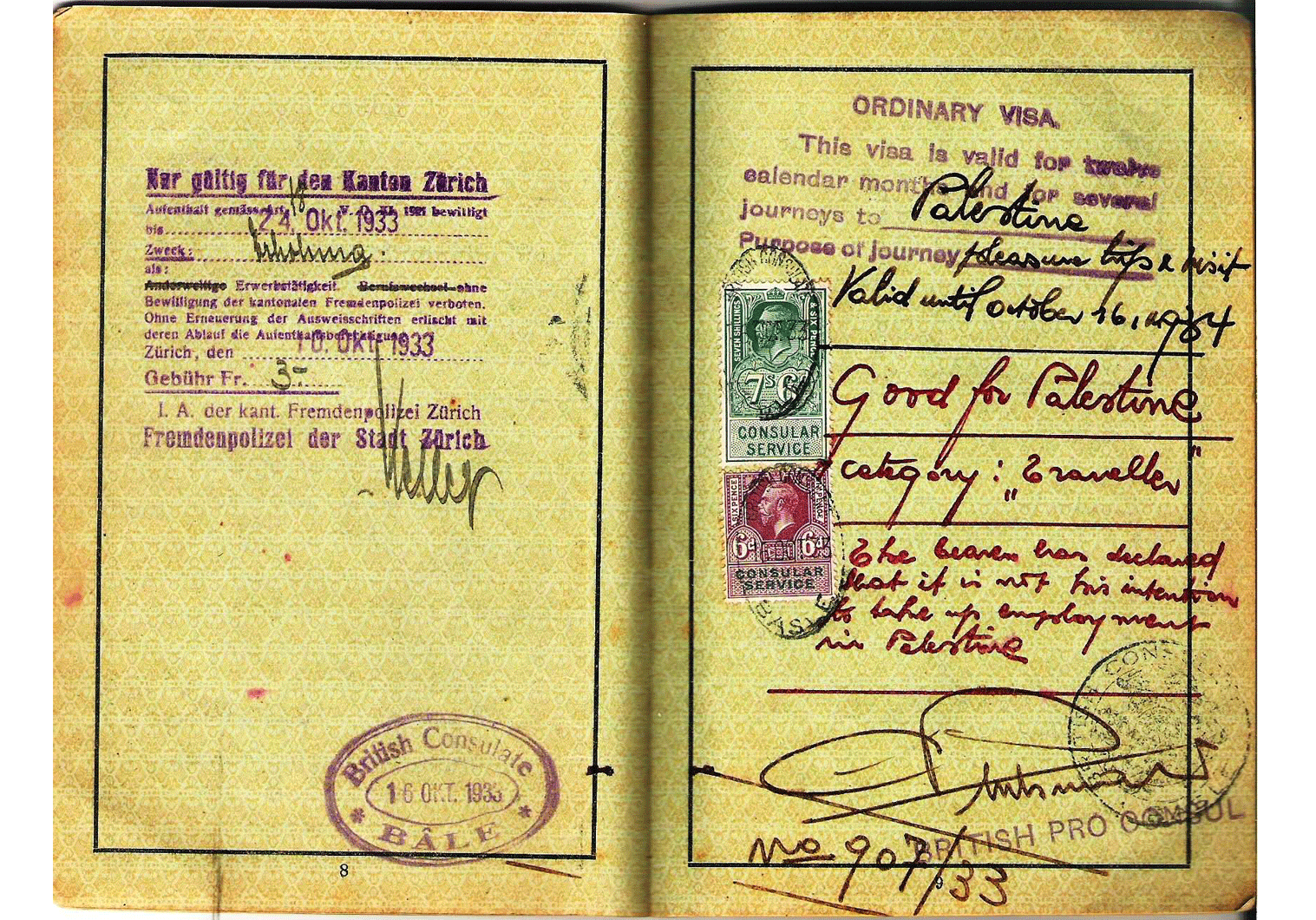

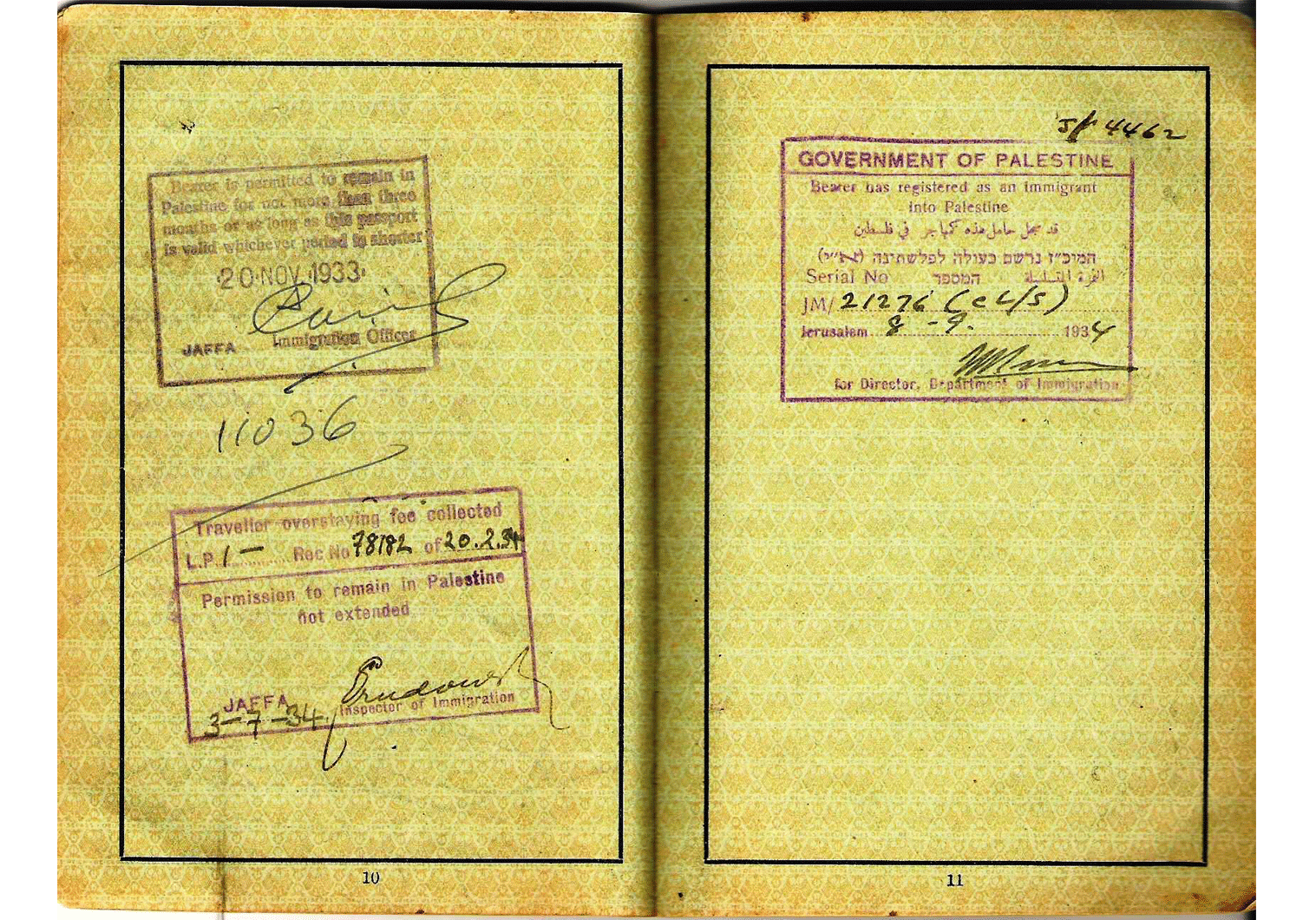

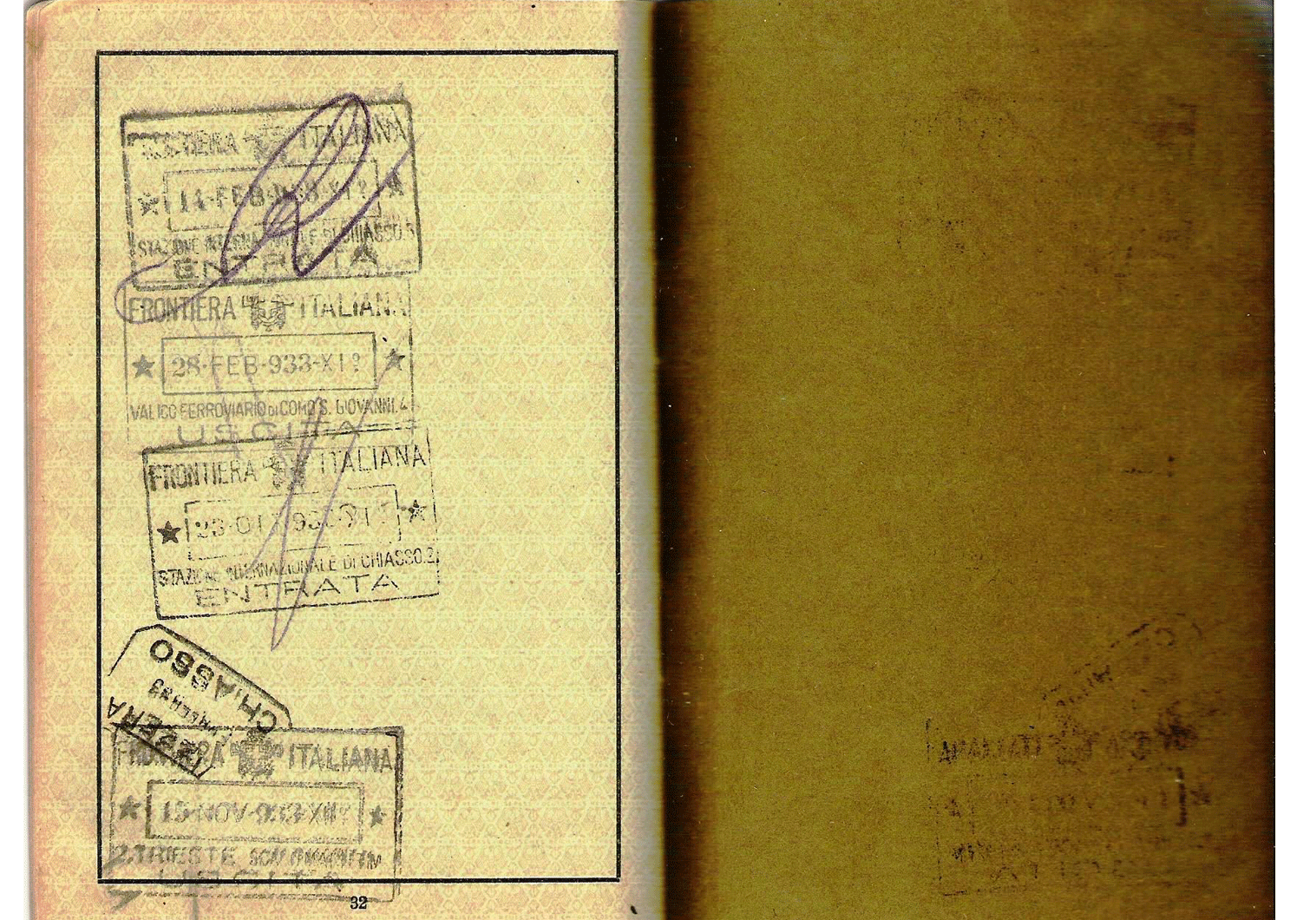

The passport in this article was issued prior to the rise of Adolf Hitler but was used to escape Nazi Germany during the first year. The holder crossed the border into Switzerland and applied for a “travelers” visa at the British consulate in Basle on October 16th 1933, which allowed him to arrive to the Mandate on November 20th, and after exceeding his legal period of time, and paying a fine of 1 pound, he managed to get himself the status of an immigrant in 1934.

Hermann here was one of the lucky ones. The passport was issued to him (1932) by the same official who issued to him his free exit visa the following year. We can only presume that by this time he managed to leave with some of his possessions and arrive calmly and easily at Jaffa port. As history has shown us, not many were as fortunate as he was and though a large amount of Jews managed to leave Germany before the borders shut down in October of 1941, a substantial amount continued to suffer and eventually murdered during the war.

Thank you for reading “Our Passports”.