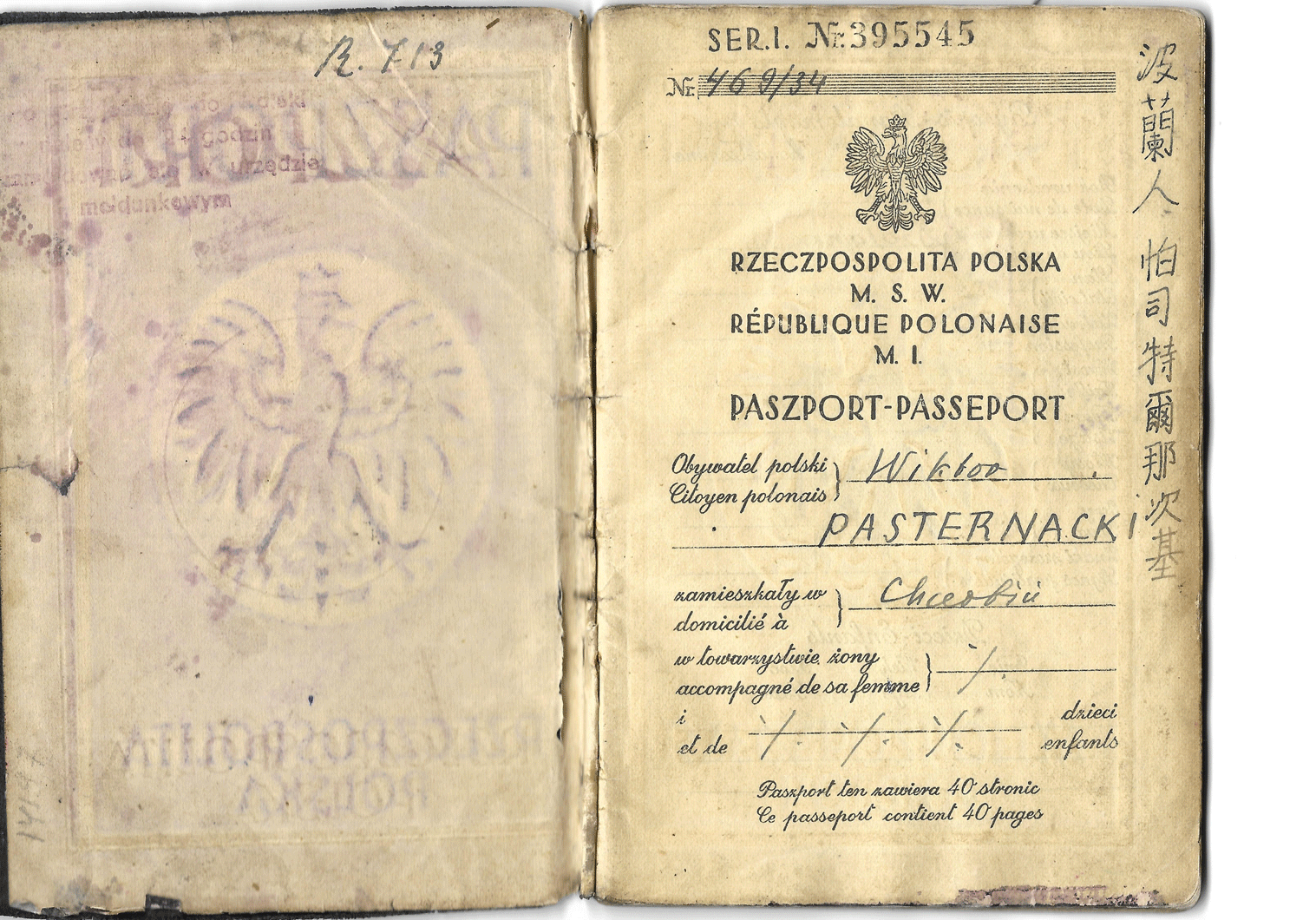

Important Harbin issued passport

Far East Polish consular sample.

When we collect samples, we try and locate the rare consular issues, those that were issued abroad and thus harder to come by. The rarity of such samples depends on the time and location of their issue and sometimes they can be unique treasures indeed. The item in this article may not be rare, but the location and applied stamps make it an attractive piece.

September 18th 1931 was a crucial date in the history of modern China. From this month onwards, starting with Asia and ending with Europe, events would spiral from a regional conflict into a world war.

The above mentioned date marks the Japanese invasion of North-Eastern China, a region known as Manchuria (a point needs to be made here: prior to the invasion, the Japanese had an enclave in the Dalian peninsula, Port Arthur, called Guan Dong Zhou Ting (关东州厅) ceded to them following the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, which was a Russian naval base).

The Japanese, using it as an excuse, staged an assault on a railway track owned by them, the South Manchurian Railways, later to be known as the Mukden Incident, to invade North-Eastern China. This led to the establishment of Manchukuo. The new state began to function and run like any other country: separate banks were erected (side-by-side to existing Chinese banks), issuing of currency and postal stamps as well. Manchuria became Manchukuo after it “gained” independence on February 18th 1932, with Puyi being its head (from 1908 the last emperor of Imperial China was Puyi. He continued to live in Beijing, the Forbidden City, but was later expelled. He settled in Tianjin city, in a Japanese concession, from 1925-1931. He was declared emperor of the Manchurian Empire in 1934 and his “reign” lasted until 1945, the year Manchuria was liberated by the Red Army). But in fact it was controlled by the military and Japanese officials who actually ran its economy & foreign relations.

The League of Nations received the Chinese official protested printed report, printed by the Foreign Ministry press at Nanjing, in 1932. Detailed accounts of Japanese actions were included, covering many subjects and issues following the invasion and its effect on the local population, and this lead to the ultimate decision by the League of Nations (after accepting the Lytton Report) to reject Japans claims and explanations and to take China’s side on the matter. Japan withdrew its membership from the League of Nations in 1933.

In spite of the League of Nations’ approach, the new state was diplomatically recognized by the following countries (according to year):

El Salvador (1934), Dominican Republic (1934), Soviet Union (1935), Italy (1937), Spain (1937), Germany (1938) and Hungary (1939); and after Pearl Harbor by the following: Slovakia (1940), Vichy France (1940), Romania (1940), Bulgaria (1941), Finland (1941), Denmark (1941), Croatia (1941), Thailand ( 1941) and the Philippines (1943).

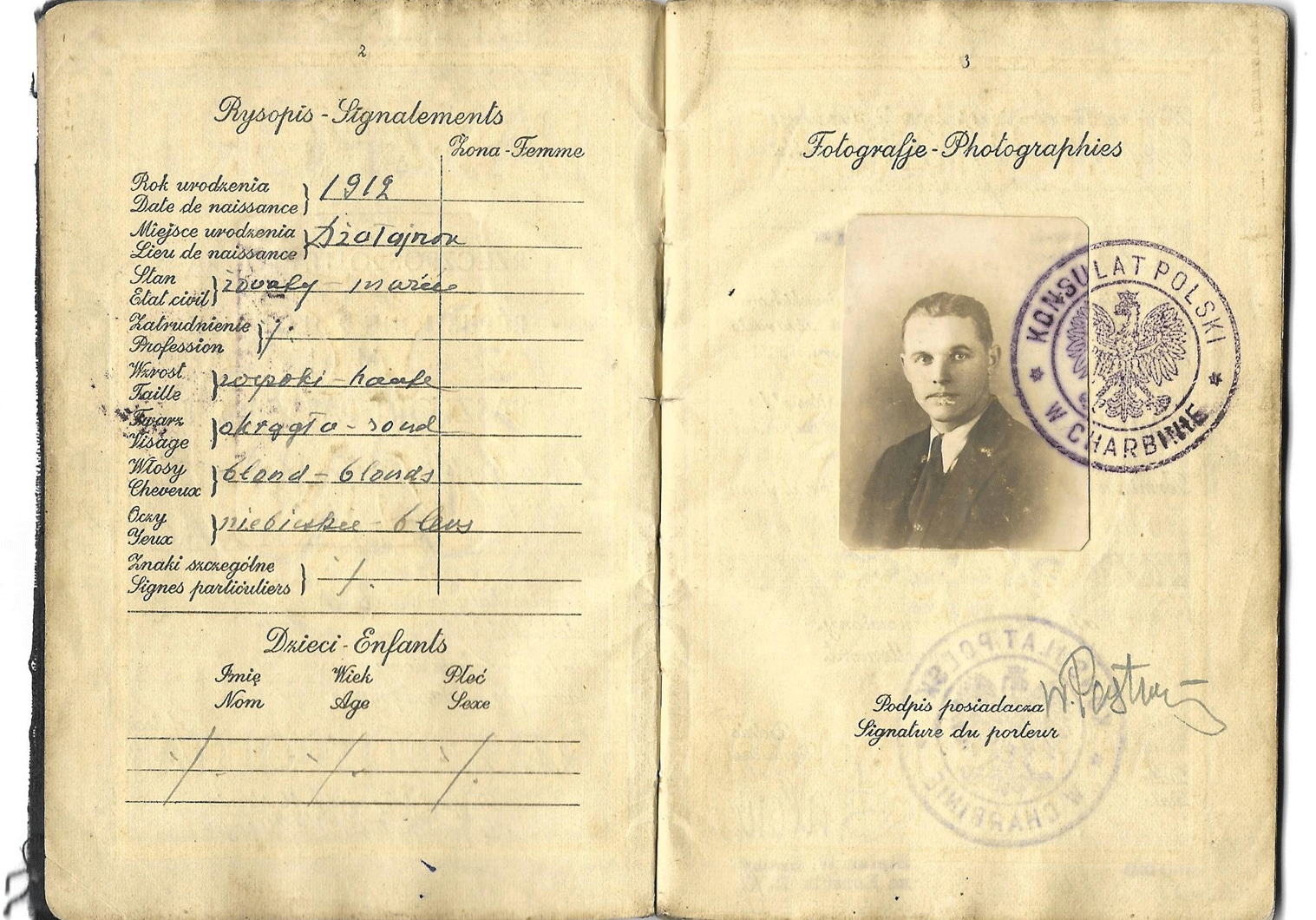

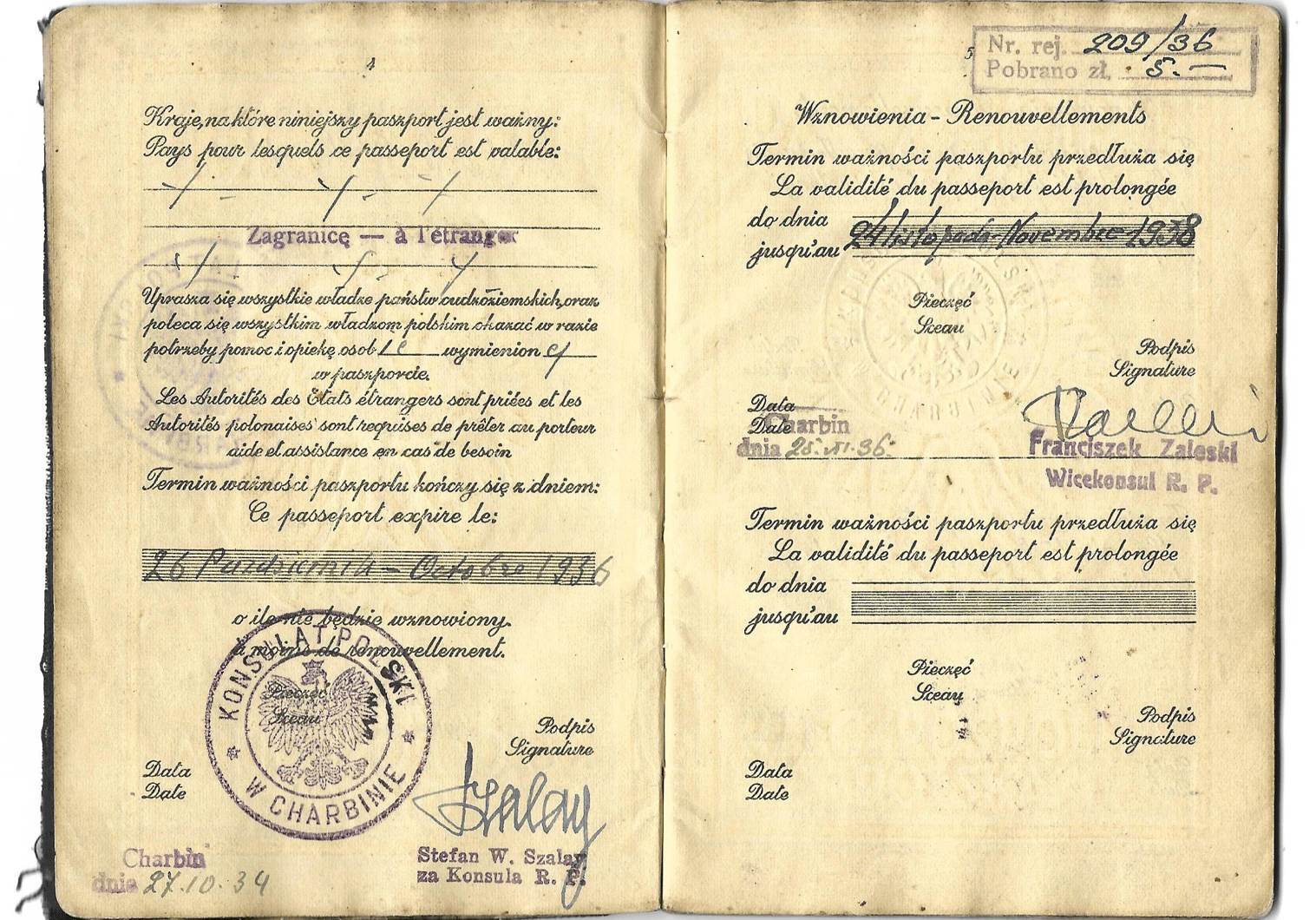

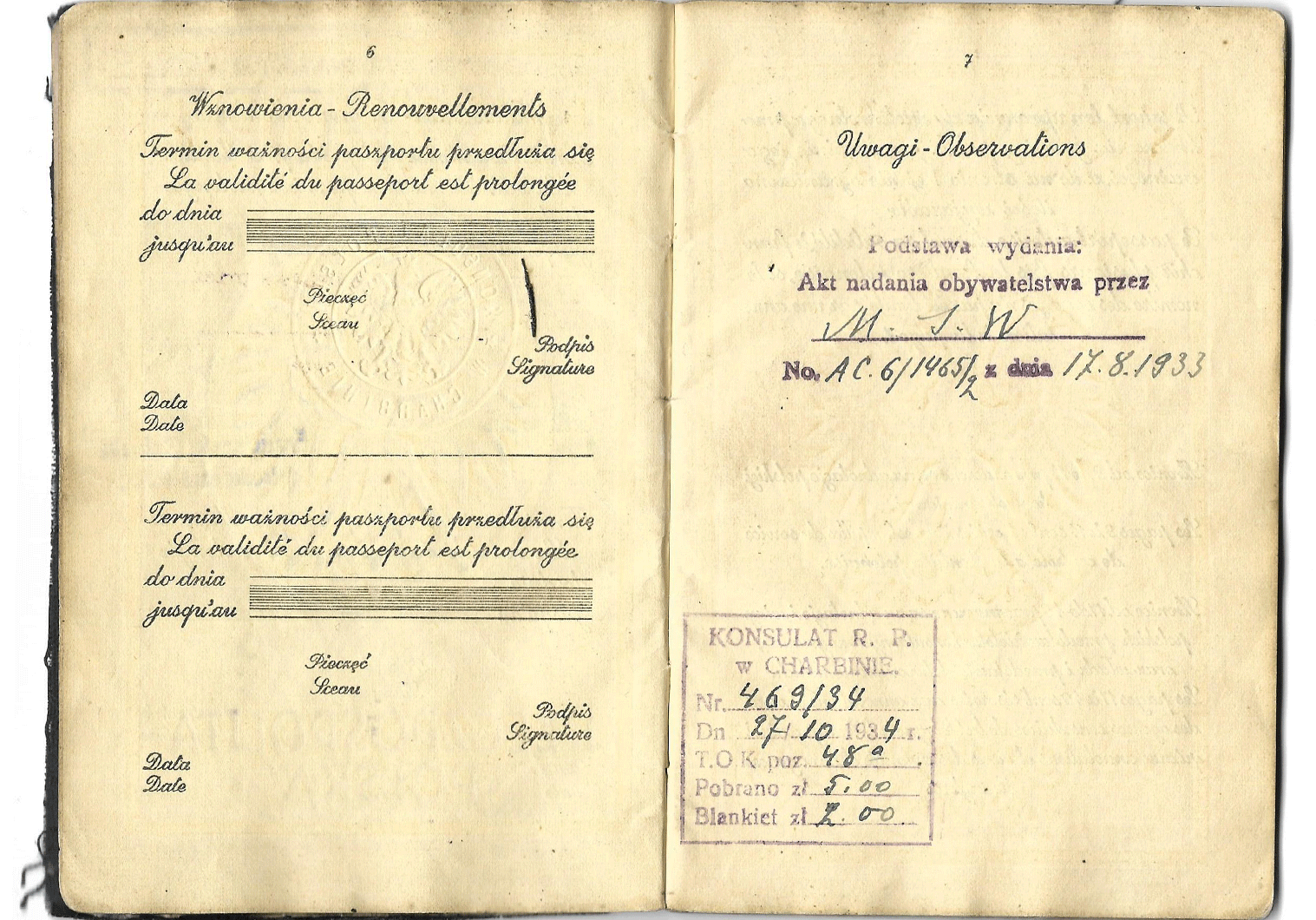

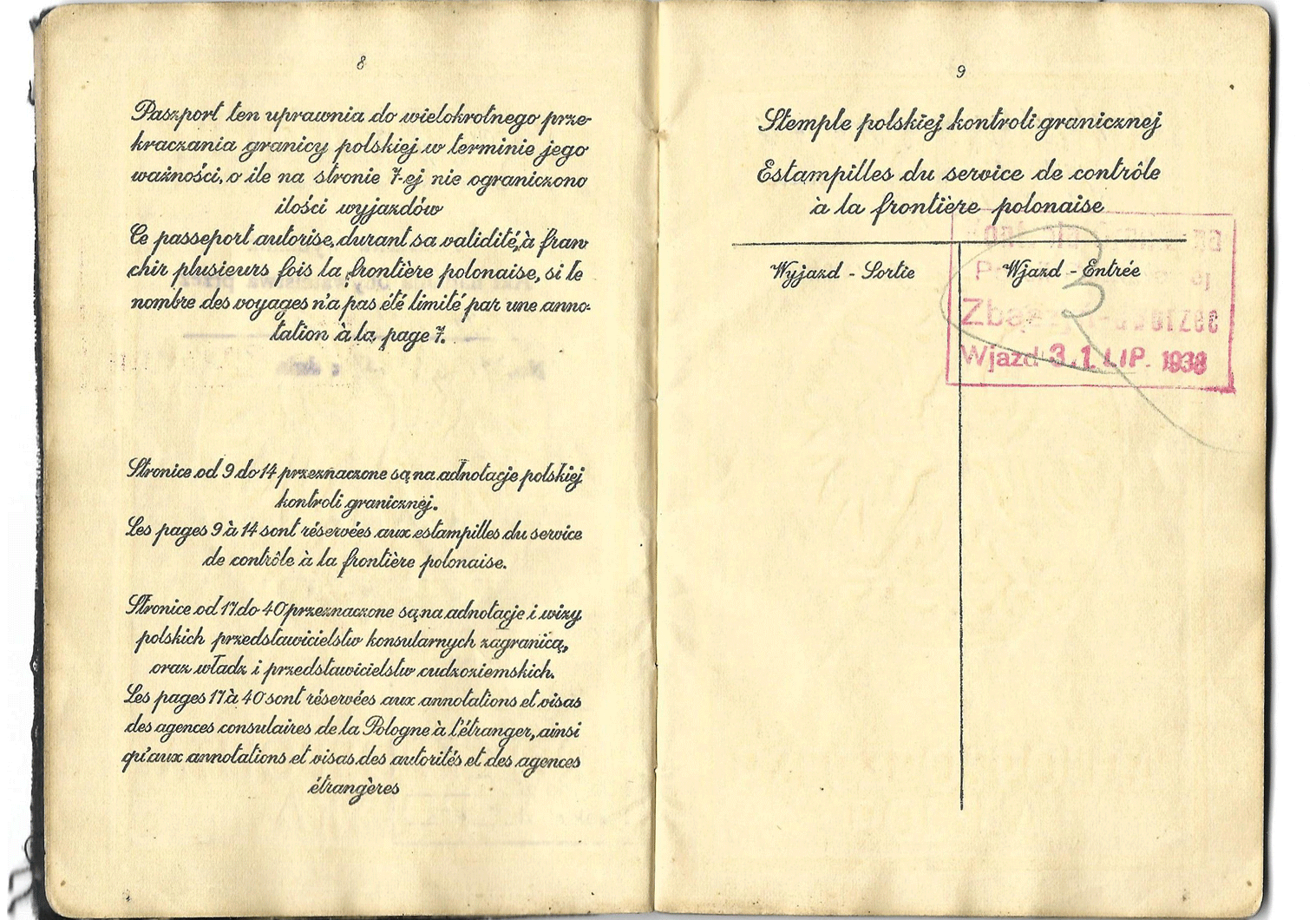

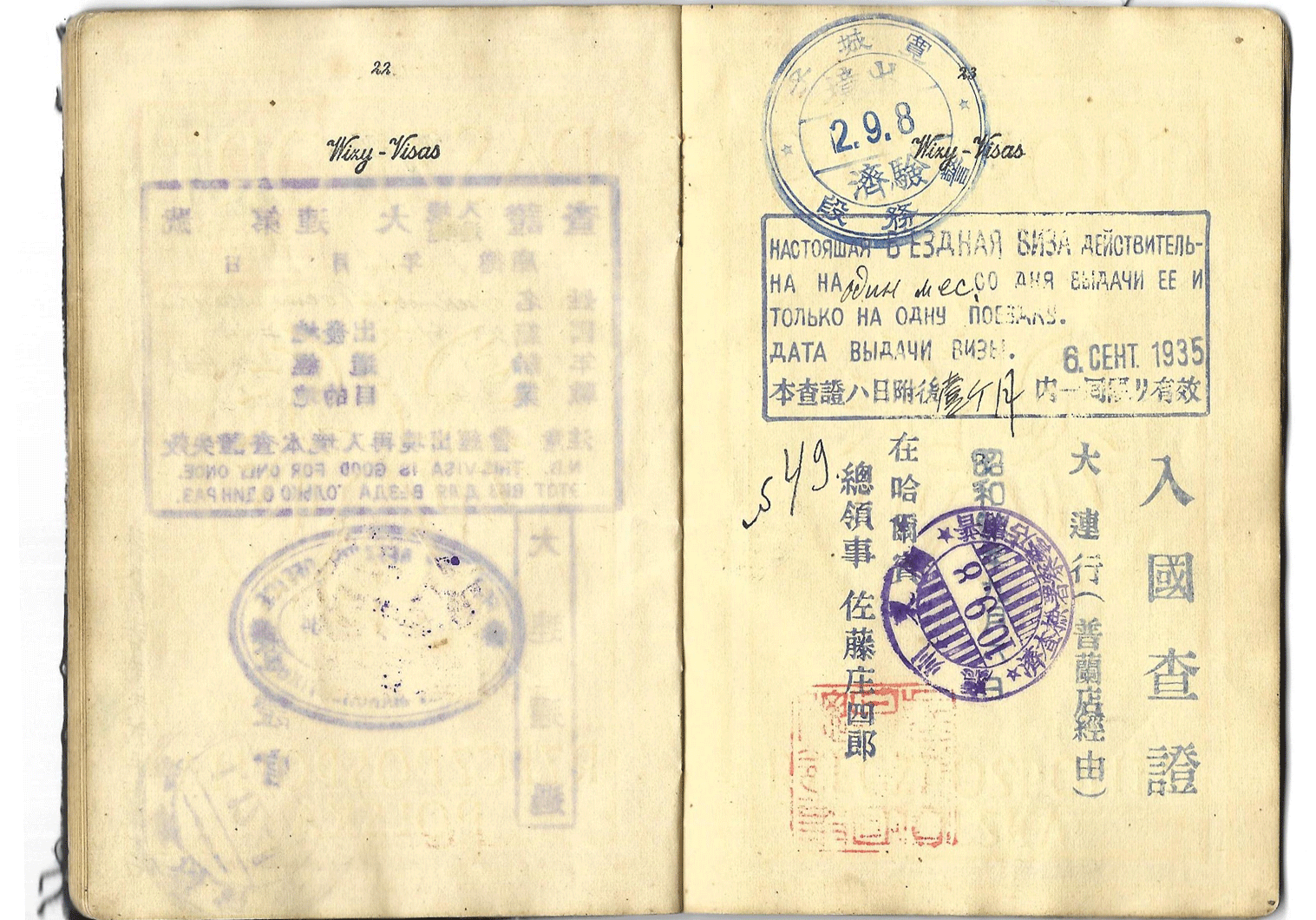

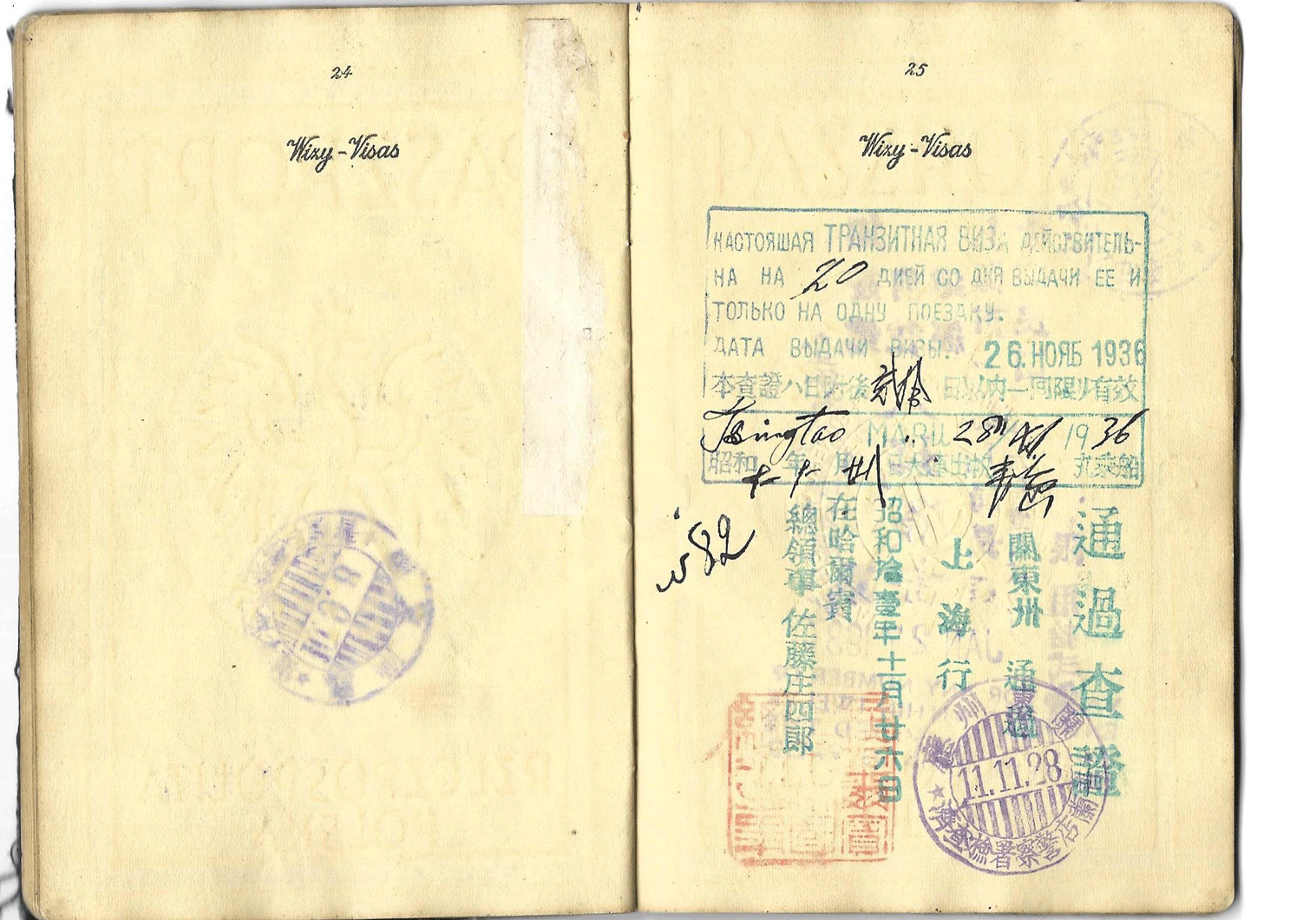

The travel document in this article was issued by the Polish consulate based in Harbin on October 27th, 1934 by diplomat Stefan W. Szalay and later extended again by another official Franciszek Zaleski on July 25th two years later. This time the document was valid to November 24th, 1938, and seems that for this reason, and others that will be mentioned about its holder it was used to return home that year.

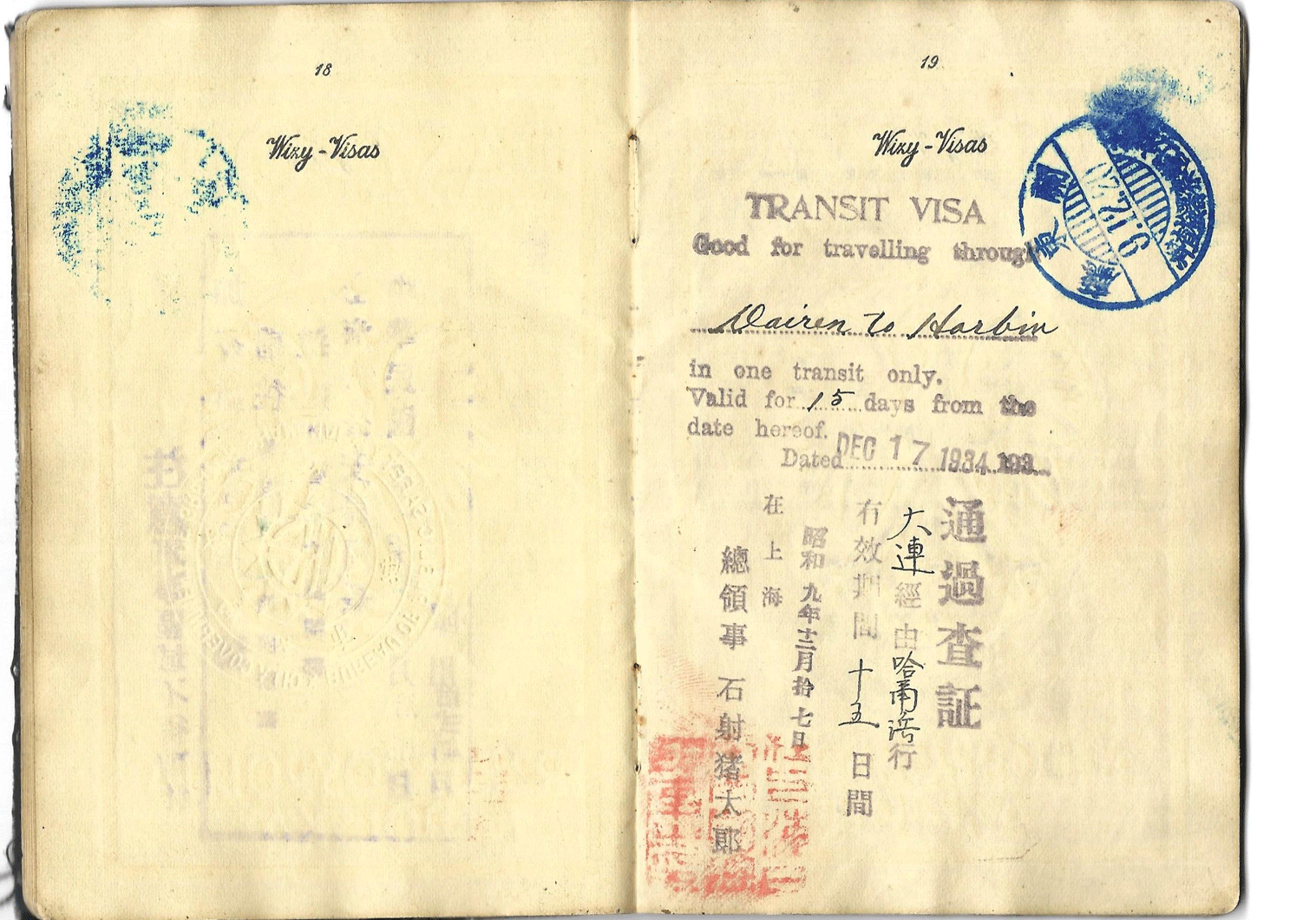

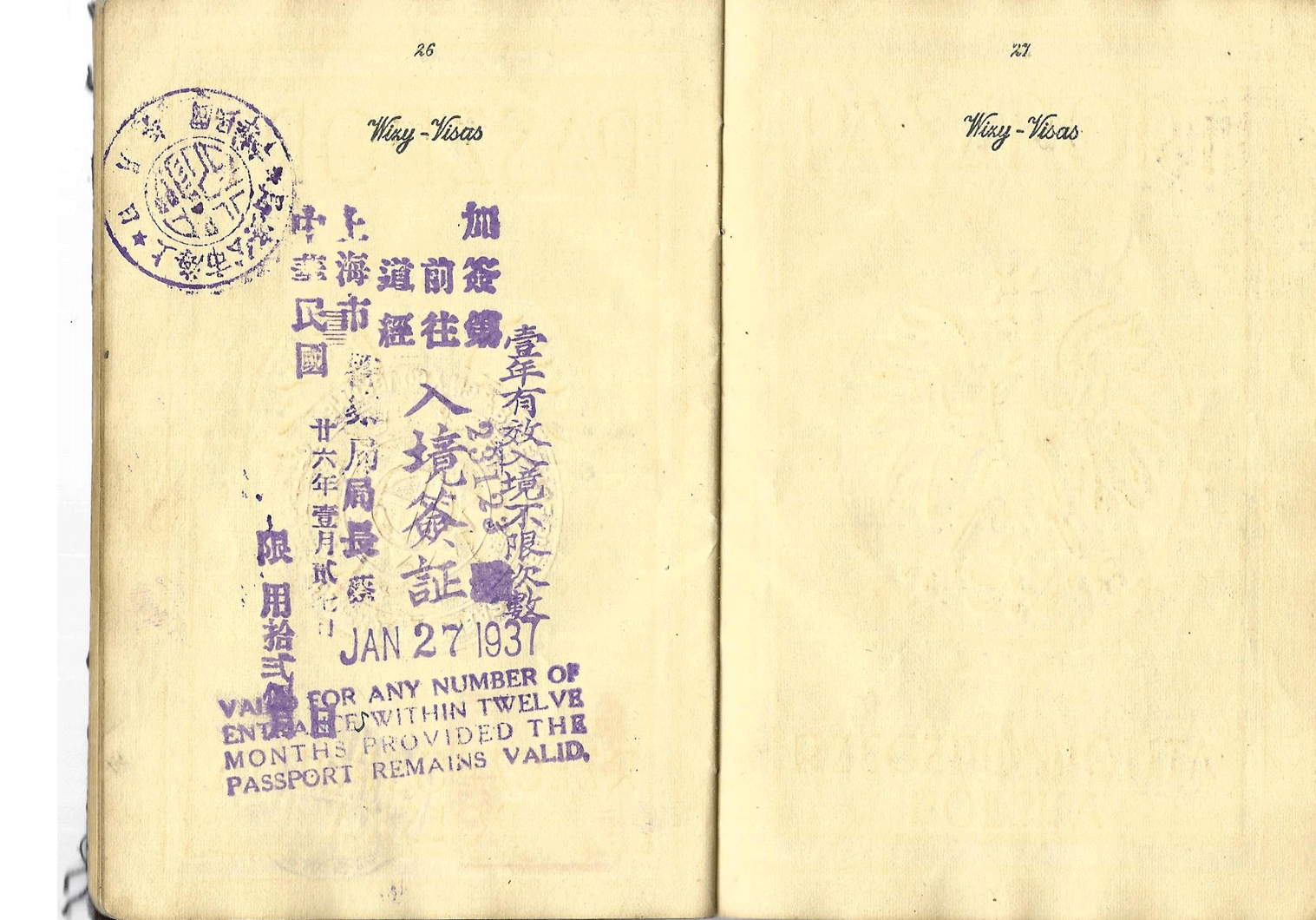

Passport No. 469/34 was used for a period of 4 years in China, and well-travelled in areas under both Japanese & Chinese control, for the routes of Harbin-Dairen-Shanghai.

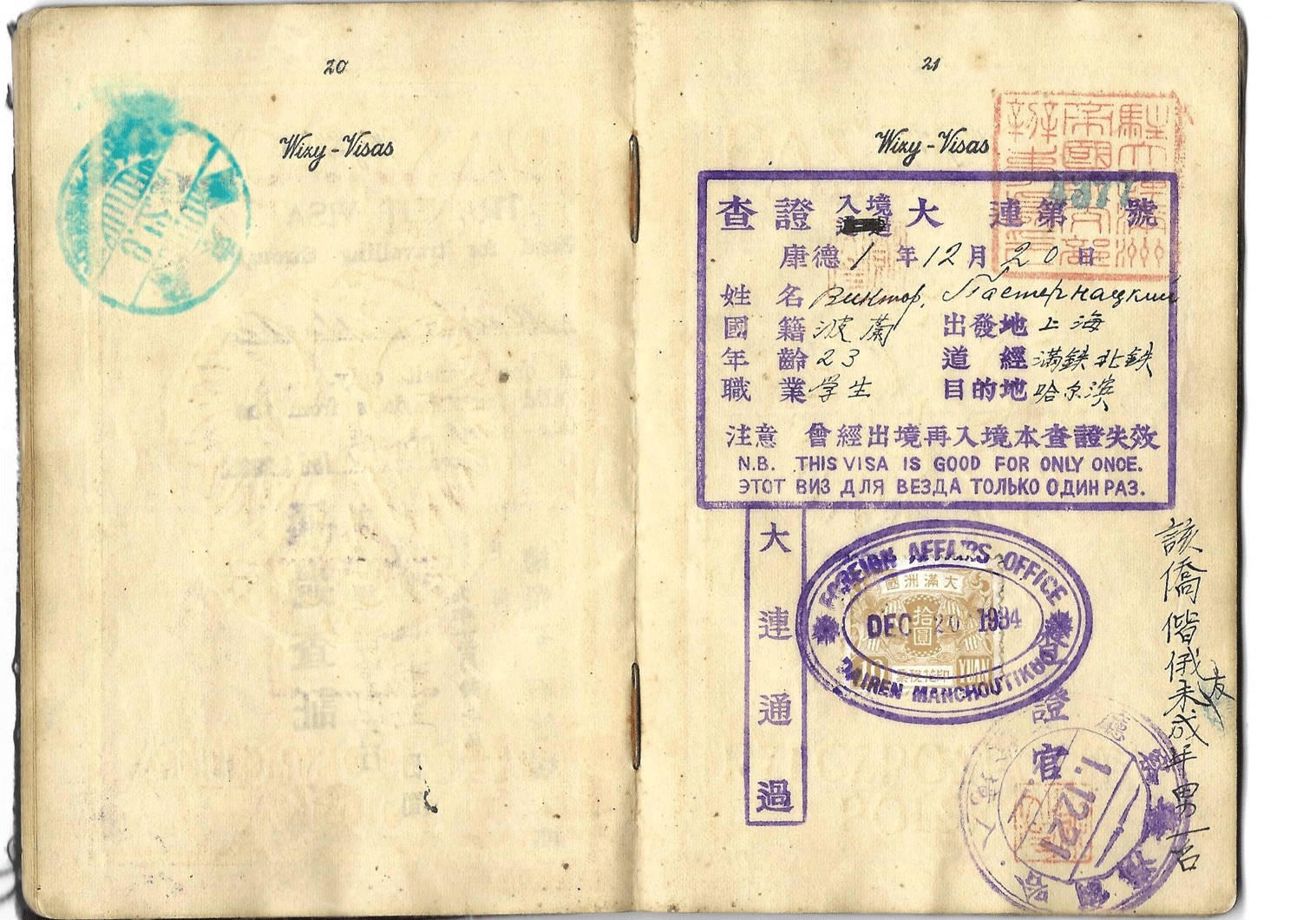

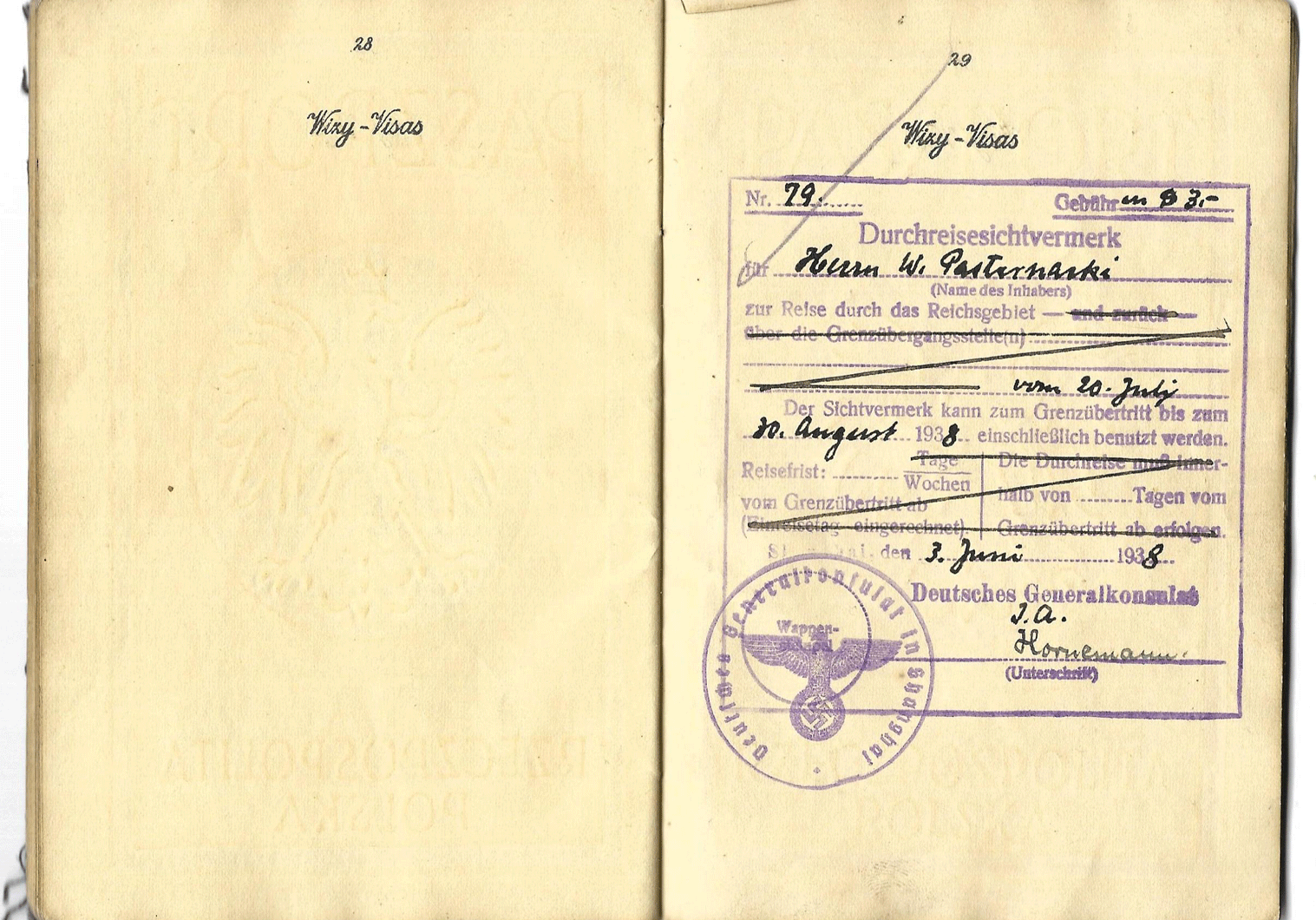

This exceptional document was issued to then student Wiktor Pasternacki, aged 22, who according to online records was studying at the Polish Gymnasium at Harbin, and upon completion of his studies returned home to attend military service.

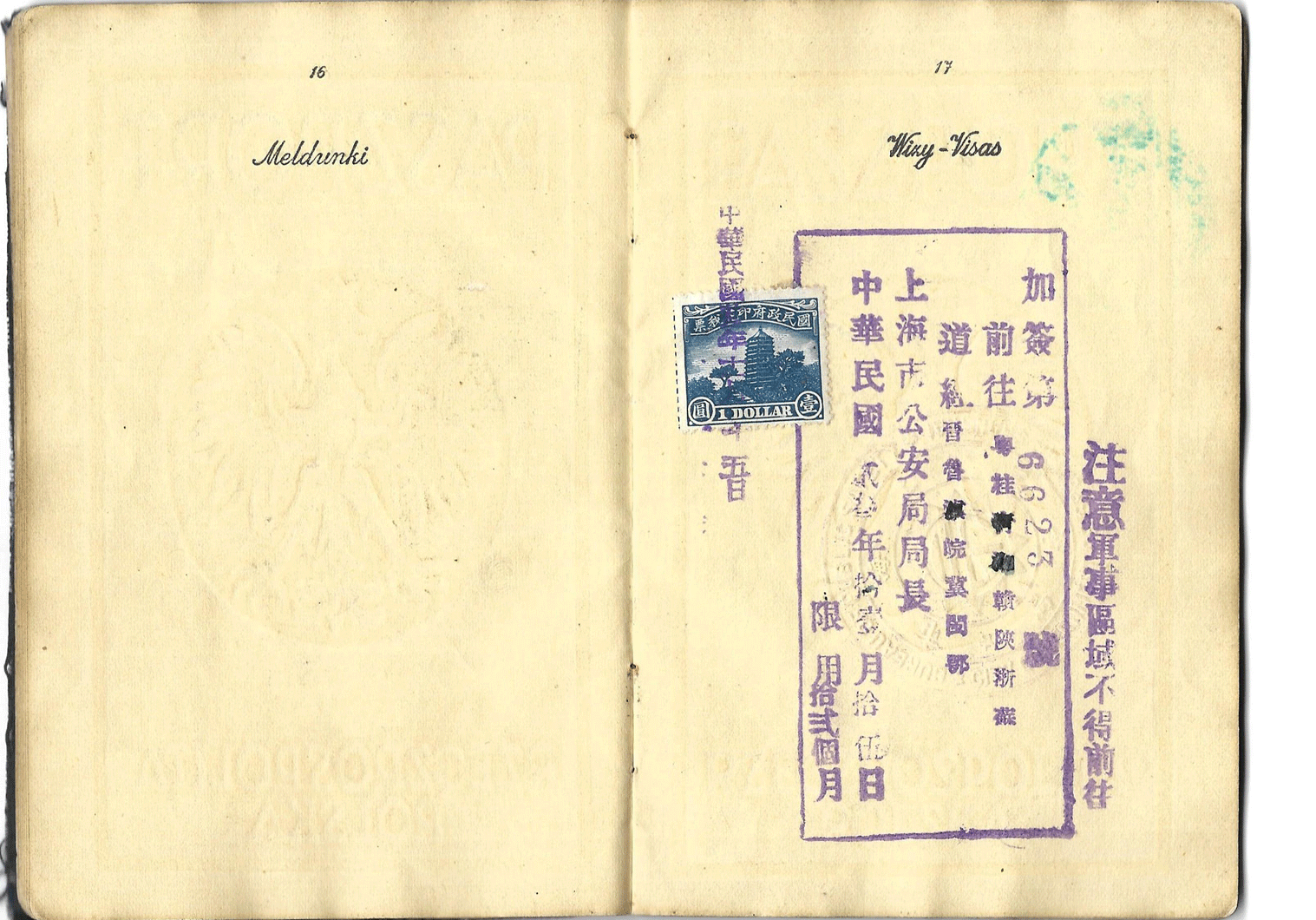

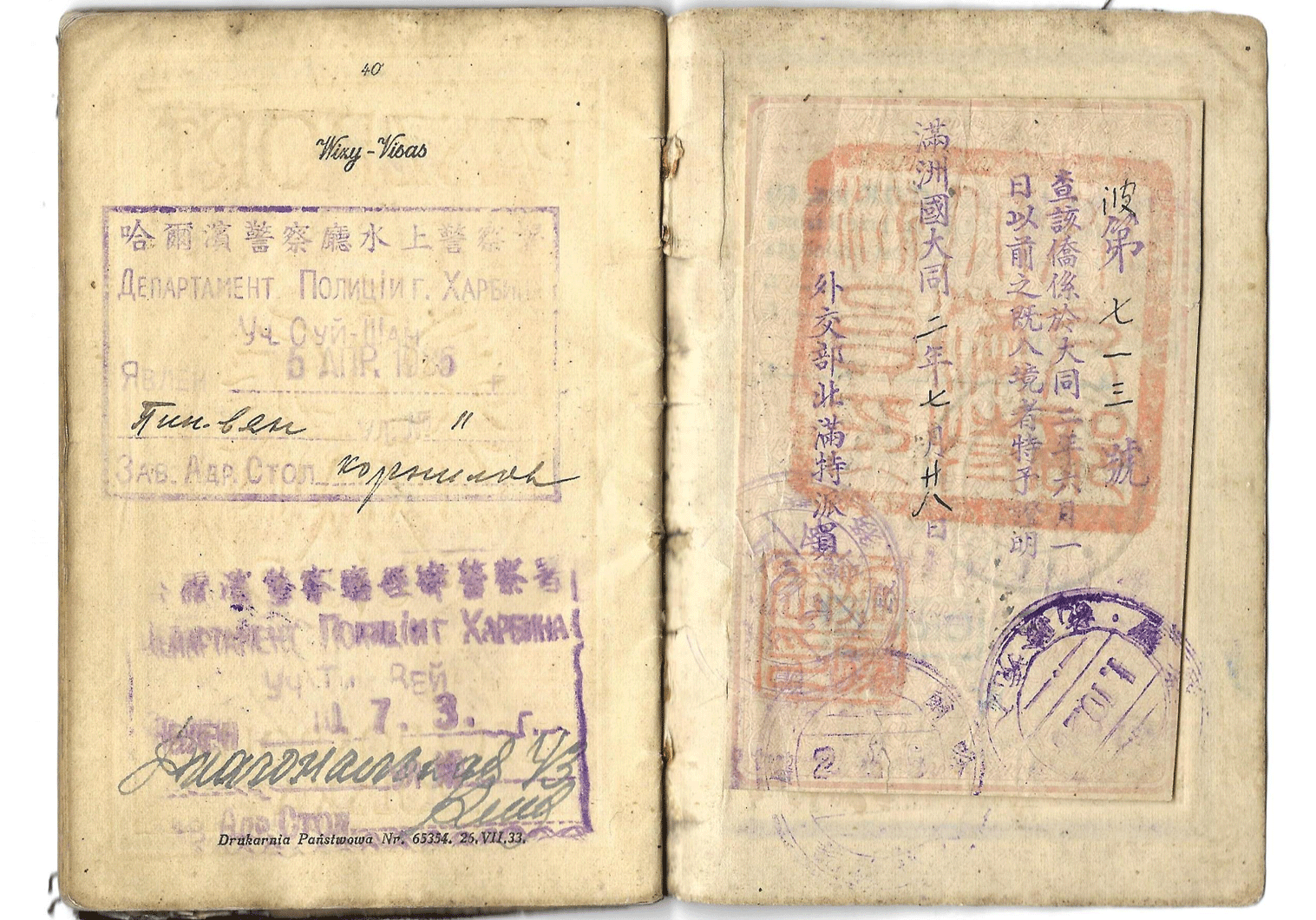

The passport has overall 7 visas: x3 Japanese, x2 Chinese and x2 Manchurian issued, one at the special Manchurian northern branch of the Foreign Office by official Shi Lu Ben (施履本), who became Manchurian Foreign Office official in the early years of the Japanese occupation (the same position he held before 1931 for the Nationalist Government) and another at their southern-tip FO branch at Dairen.

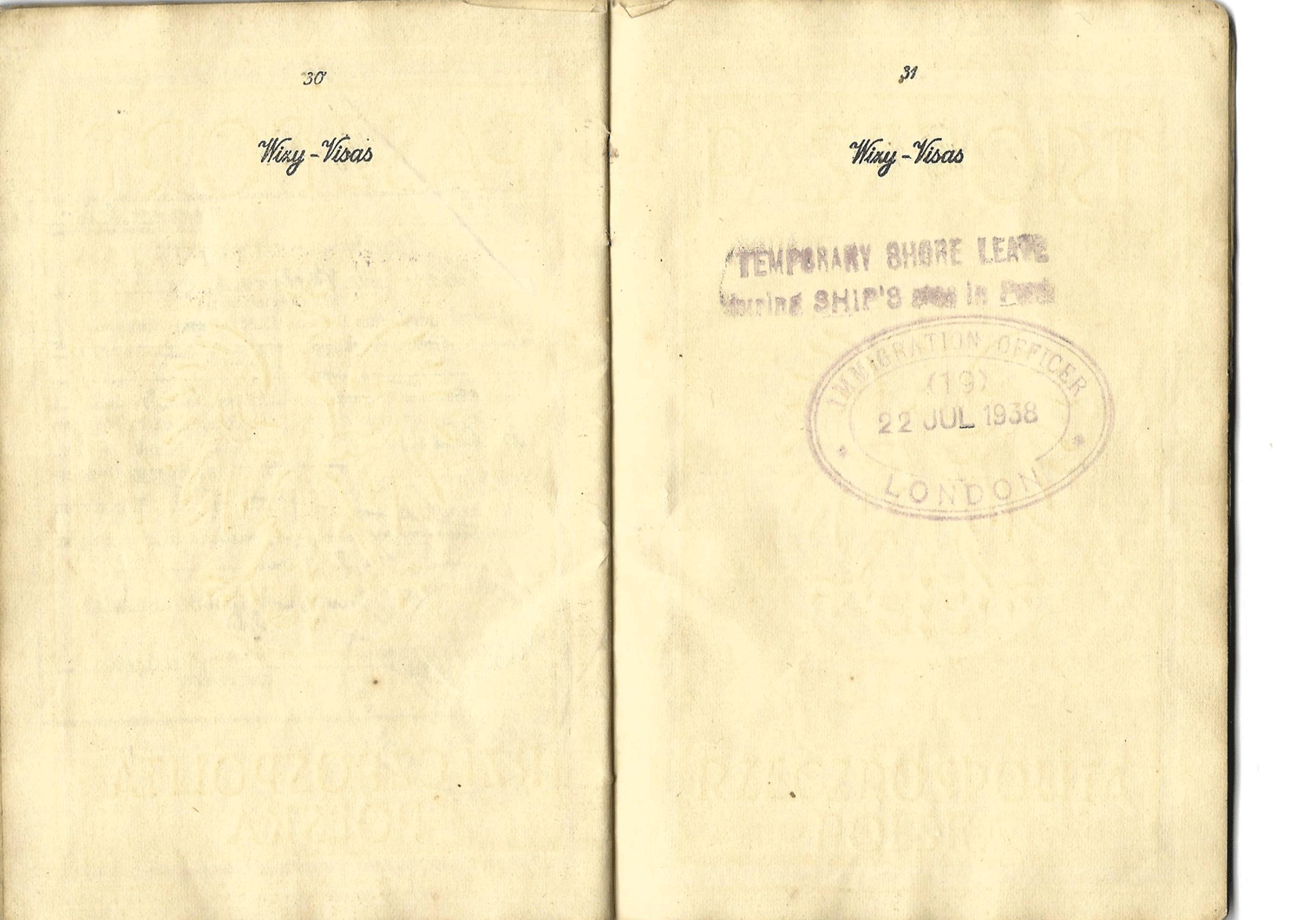

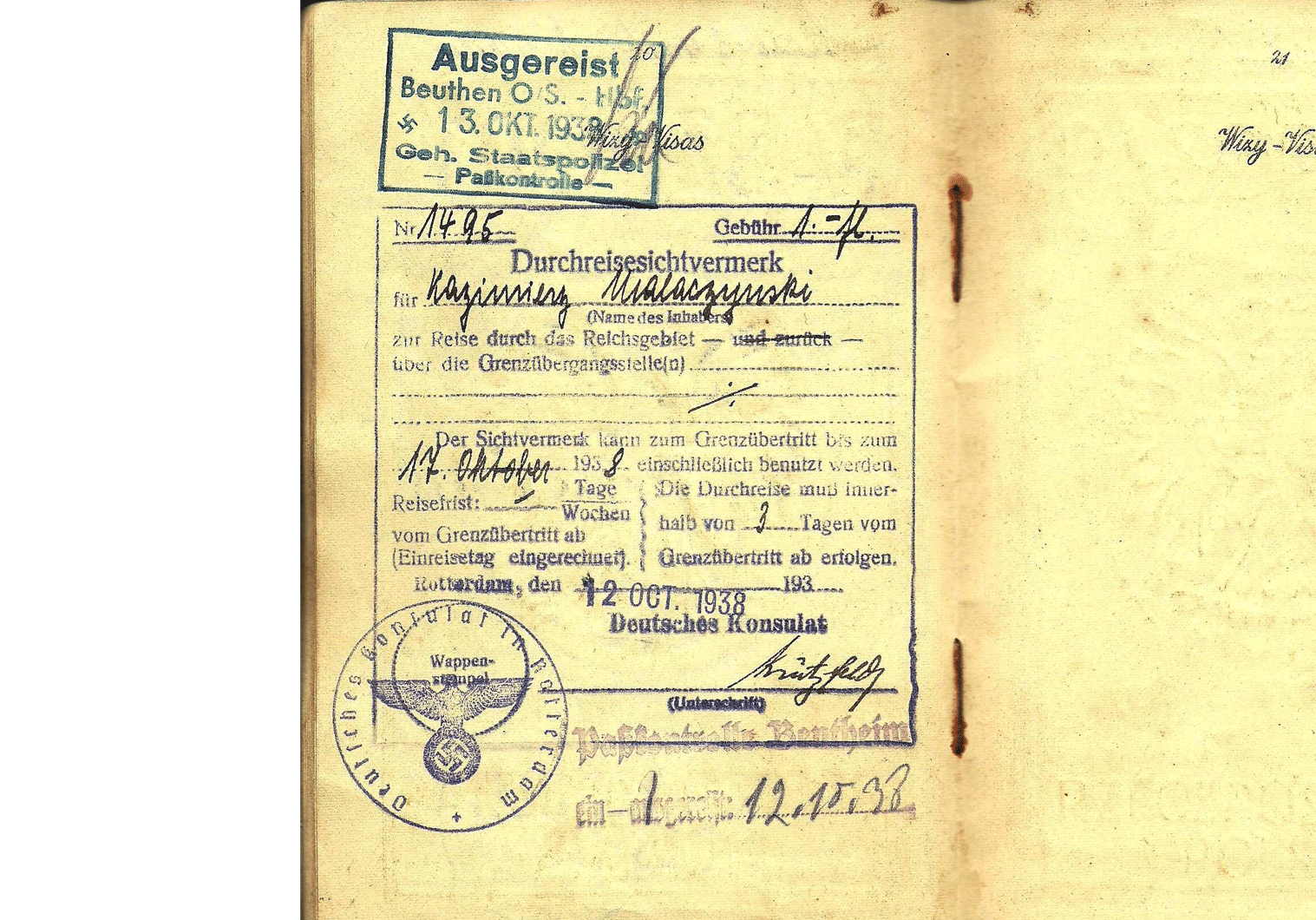

The holder of the passport retuned home apparently via boat that took him, without any offshore stays at Hong Kong or Colombo to the UK and from there to a Polish port most likely, since we cannot locate any continental transit markings, except for one at London dating from July 22nd, though there is a German visa issued at Shanghai and possibly not used at the end (though entry point into Poland was the joint German-Polish border control at Zbąszyń from July 31st, but no German markings can be found inside; this point would also have a Gestapo border-checking office and one of the few such stamps inside passports with this interesting office can be located inside some passports, see example added).

Japanese visas were issued by diplomats Ishishe Inutaro (石射猪太郎 – 1887-1954) at Shanghai & Sato Shoshiro in Harbin.

Wiktor Pasternacki entered military service at the cadet school in Grodno and when war erupted, he fought at the capital and managed to escape to Bialystok, his plans, according to the material online, was to join a distant family relative in Lithuania but was caught by the Rd Army. Lucky for him, his passport, which was on him, caught the attention of his captors which deemed it important to send him for further interrogation in Moscow, something that most likely saved his live and not ending up at Katyn. He was deemed a spy and sentenced to 10 years of hard labor, but was released from imprisonment following the Sikorski–Mayski agreement in 1941, joined the Anders’ Army and ended up fighting in the Middle East: British Palestine, Iraq and Italy. After the war he opted to go to the UK and from there he went with his family, wife & daughter, to Shanghai, China and then to the Philippines. According to IRO archival material from 1949 there was a set of internal correspondence between the UK & Philippines refugee offices to ascertain the next step in the family’s movements and assistance, with request to be sent to the US. The trail ends here. Further research is needed.

Have added images of this unique travel document.

Thank you for reading “Our Passports”.