Foreigner’s Identity Document

Used to escape to British Palestine.

By 1939 it was already obvious and clear to many that it was only a matter of time until war would erupt in Europe.

The writing has been on the wall for some time now, especially after the events that took place in Vienna and the Sudetenland in 1938. The German peaceful takeover of Memel and what was left of Czechoslovakia was the final wake up call for anyone who thought that appeasement was the way to avoid war with Germany.

The hostility towards Jews in Europe was on the rise, mainly after neighboring countries saw how their new neighbor, Nazi Germany, was behaving towards its own citizens. The lack of strong international reaction was a signal that not much would be done as well. The Jews in Germany were desperate to leave in any way possible. Same was for other countries which had a Jewish population. The fear in the hearts of all Jews would grow from day to day.

The Polish local government and population, with a long history of anti-Semitic hostility towards their own local Jewish population, increased its hostility towards their Jewish minority living among them after the death of their beloved president in 1935, Marshal Jozef Pilsudski. Local fascist political parties, and public figures, began to pressure the government to make legislation that would impose restrictions onto the Jews. One of the first laws put into place was the limitation and supervision of kosher slaughtering, from 1937. Some other examples:

- 1936 local business to publicly state owners names onto their business signs;

- 1937 saw the Polish medical association excluding Jewish doctors;

- 1938 restriction of Jewish lawyers from obtaining license to practice law; the same was for the Jewish journalists in the city of Wilno that prohibited any non-Jews from entering their organization (Wilno General Assembly of Journalist); October 30th 1938 threat of cancelling Polish passports for those living abroad for more than 5 years, this was imposed following the events in Nazi Germany (this was strictly done to curve or prevent the mass re-entry of Jewish Poles living in Germany); the Bank Polski issued provisions that excluded Jews;

Thus, as war loomed and the dark clouds began to appear on the horizon, so did the Polish Jews attempts to leave their country. The document in this article will relate to one such attempt, an elderly Jewish woman who had no official status that was trying desperately to leave.

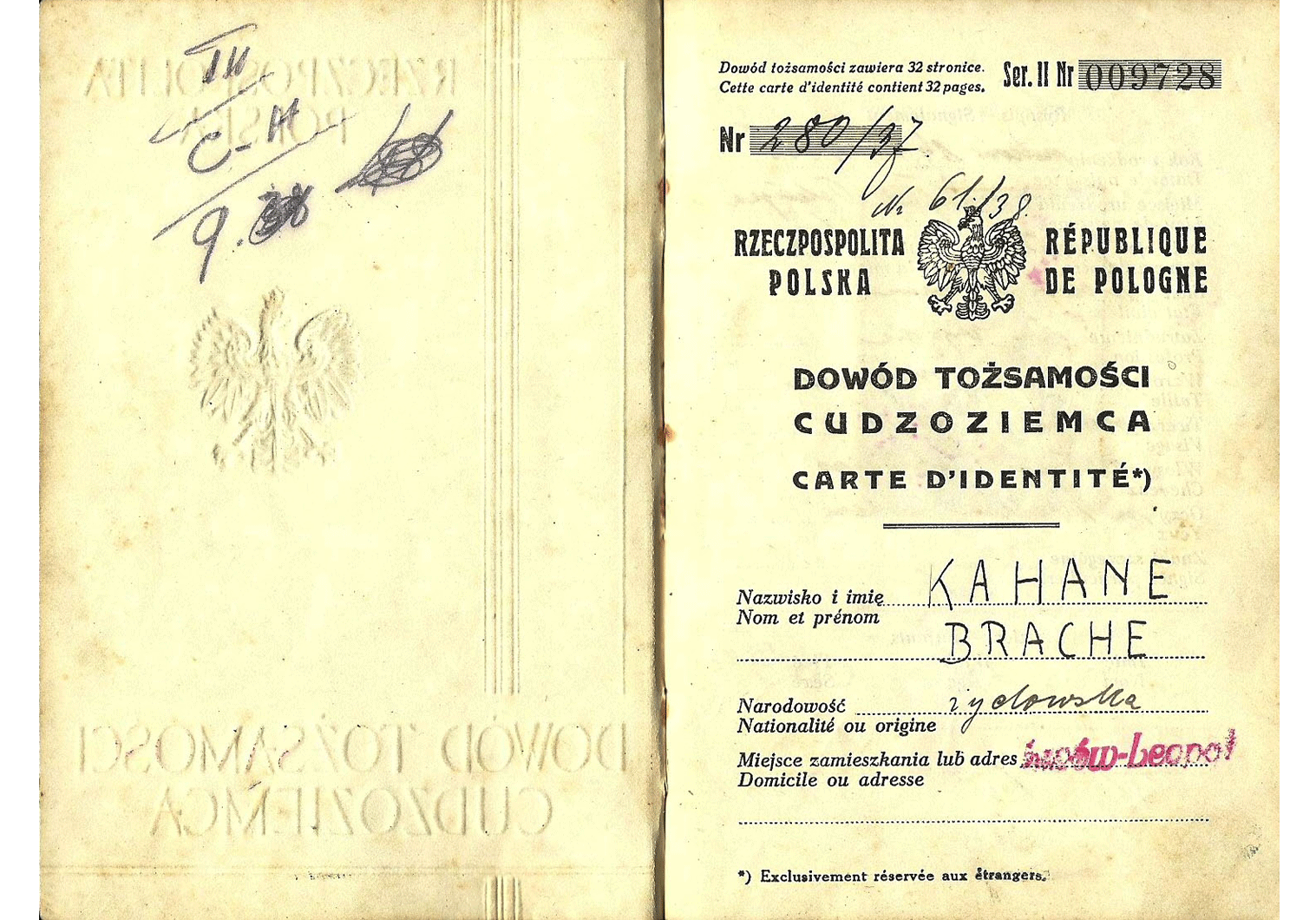

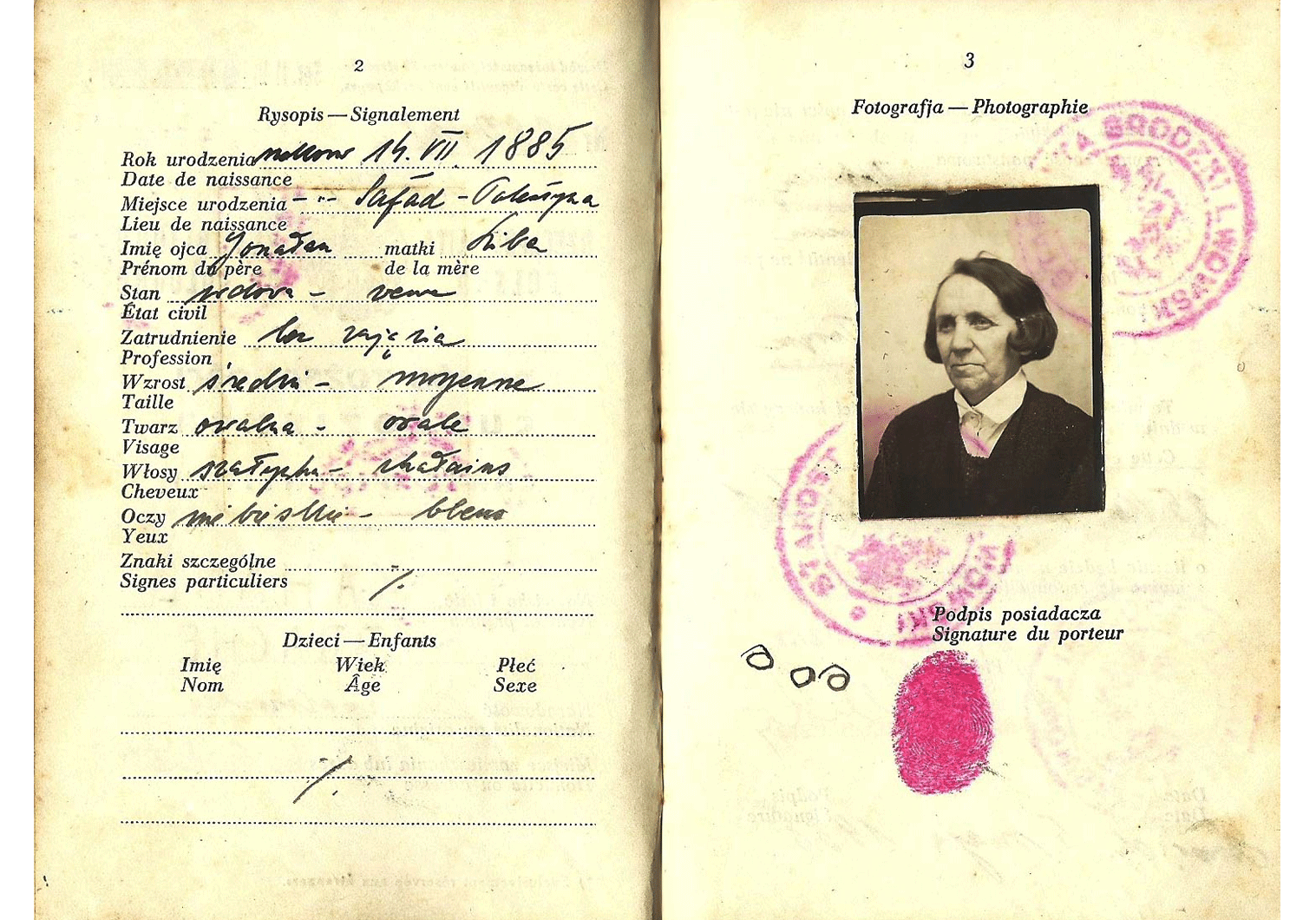

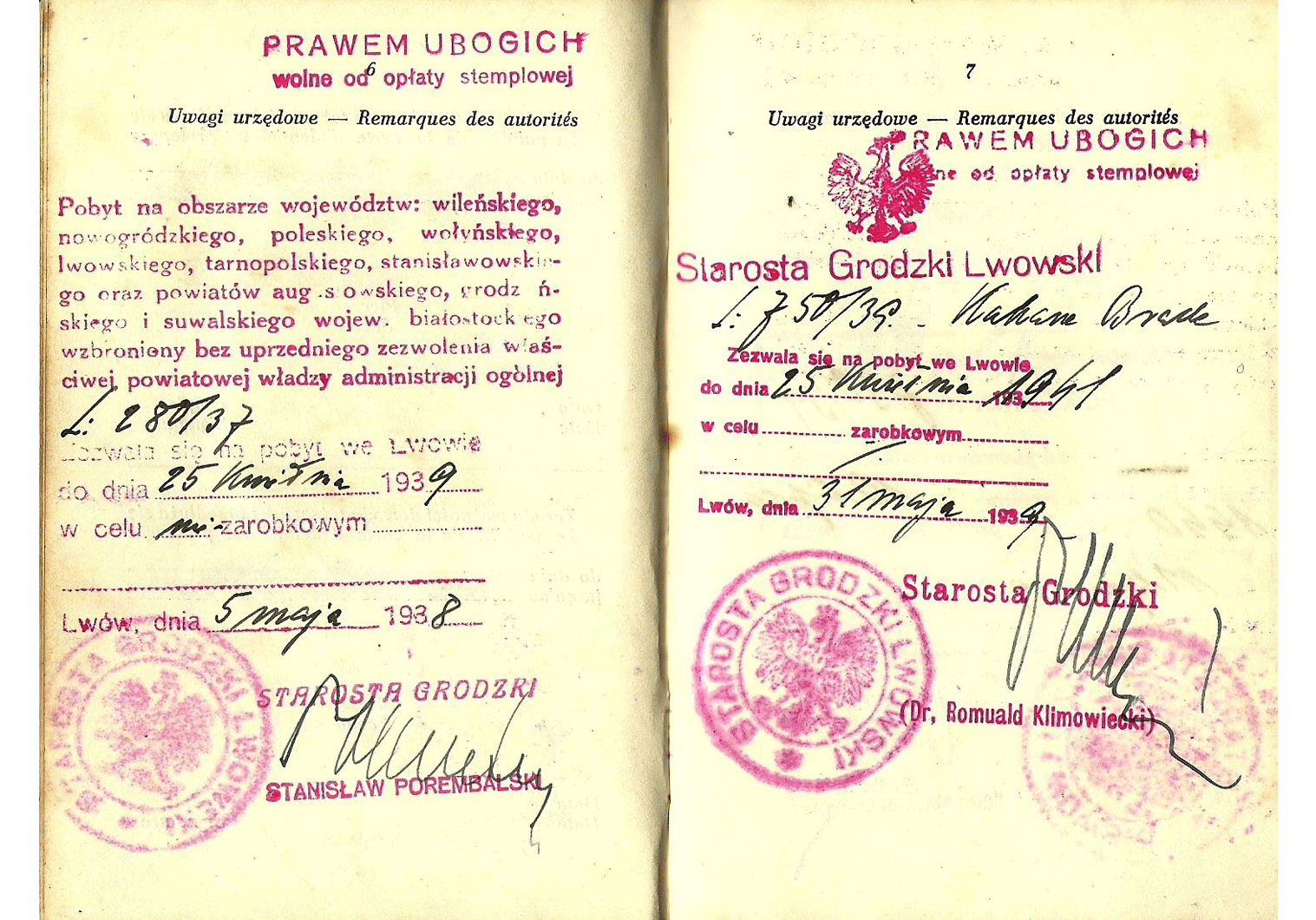

Polish Alien/Foreigner Identity Certificate (Dowod Tożsamości Cudzoziemca) number 61/38 was issued to Brache Kahane on May 5th 1938 at Lwow. Though her national status is “undetermined” and she was born in Ottoman Palestine, at the ancient Jewish city of Safad, the tile page indicates her nationality as a Jew, in itself very degrading.

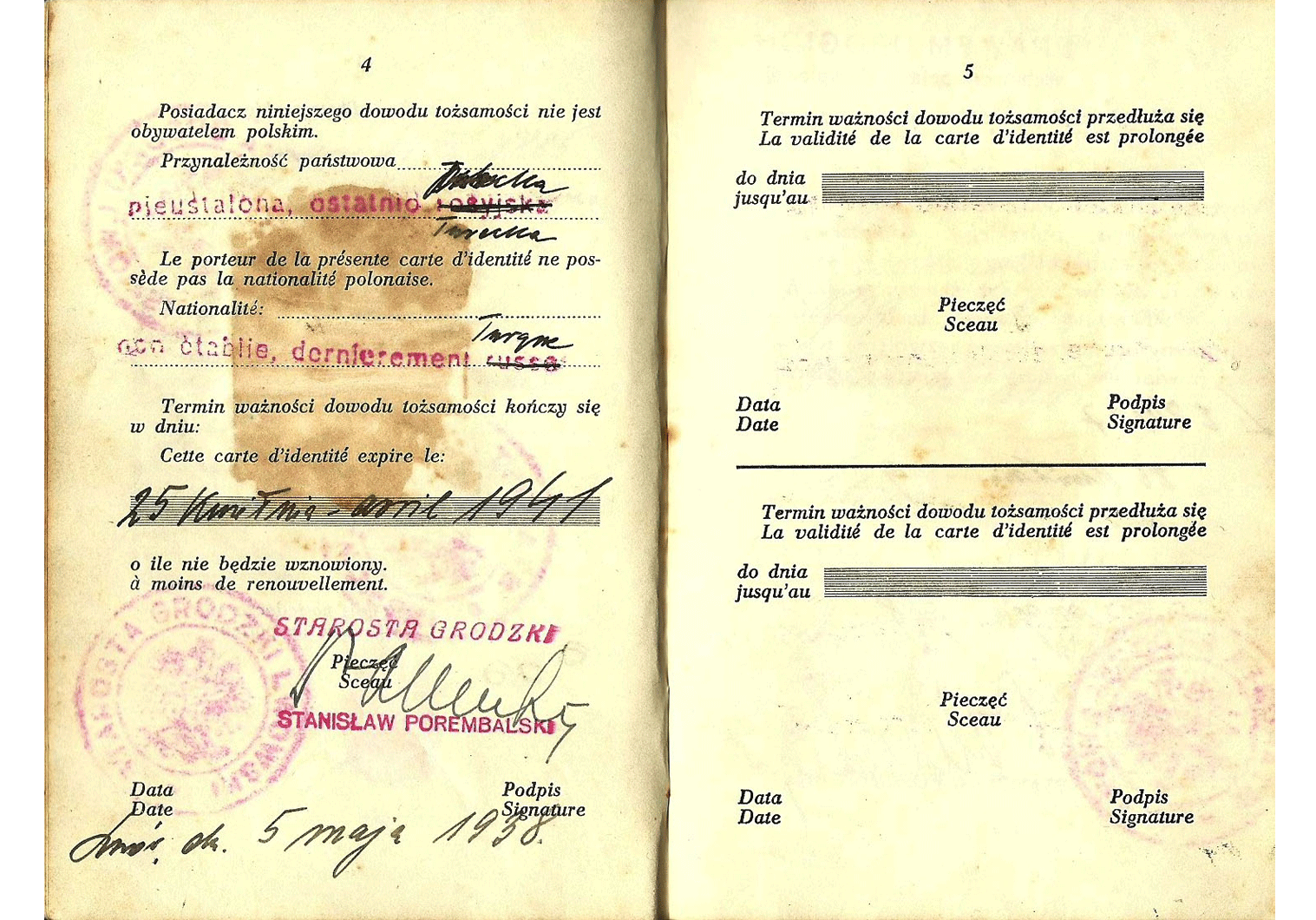

The travel document was issued by Stanisław Porembalski, who was also an army officer besides being a government official. From 1936 he was stationed at Lwow, his last official posting, and was murdered by the Gestapo after the outbreak of war in 1939; with his remains found in a small village of Kirsch, part of Kielce.

The document was extended and visaed again the following year by another government official

Dr. Romuald Klimowiecki (February 7th 1896 – June 13th 1959) who had a rich and extensive career before and after the war:

- 1917-1920 Studies in Vienna & Lwow; obtaining doctorate in law;

- 1924-1928 senior assistant at the university of Jan Kazimierz;

- 1928-1929 official work at the Ministry of Interior;

- 1929-1939 governor to various provinces throughout Poland: Sanok, Chrzanów & Lwow;

- 1934 military officer degree at reserve status (rank from 1919);

- 1935-1936 Lwow sports club president (LKS Pogon Lwow);

- 1939-1945 was a road laborer at Żółtańcach and later an accountant at Łańcut & Lwow;

- 1945-1947 Military judge at Warsaw and Krakow (dismissed due to pre-war activities);

- 1948 legal advisor at the Ministry of Light Industry;

- 1949-1959 expert and lecturer to several universities: Warsaw, Torun and Poznan.

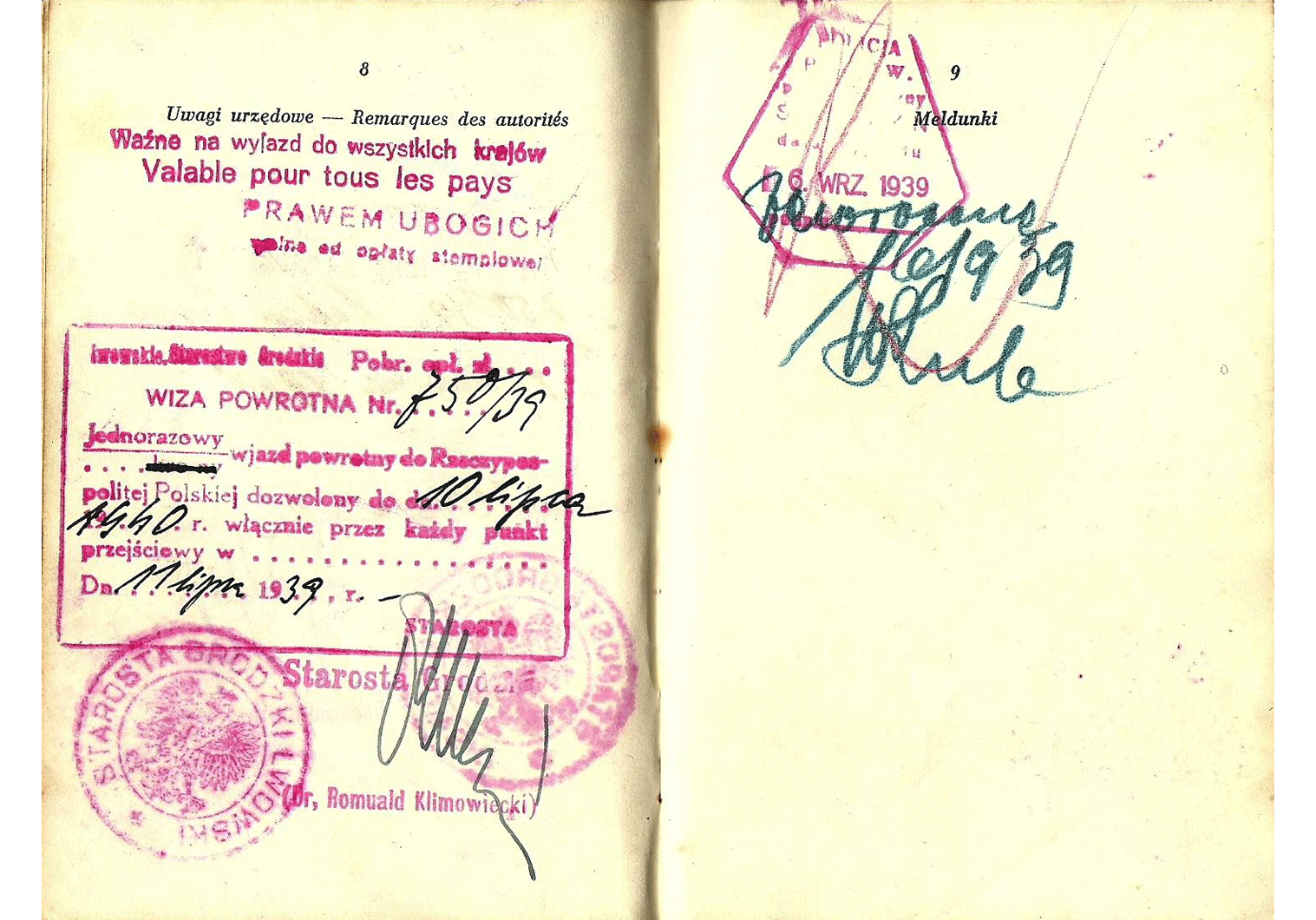

The document has endorsements indicating that she is free of any charges or visa charges due to her being “destitute” or classified as “socially poor” and without means. Other endorsements include her residence permit extended from 1939 to 1941 and a return visa back to Poland, should she decide to return, limited to one year.

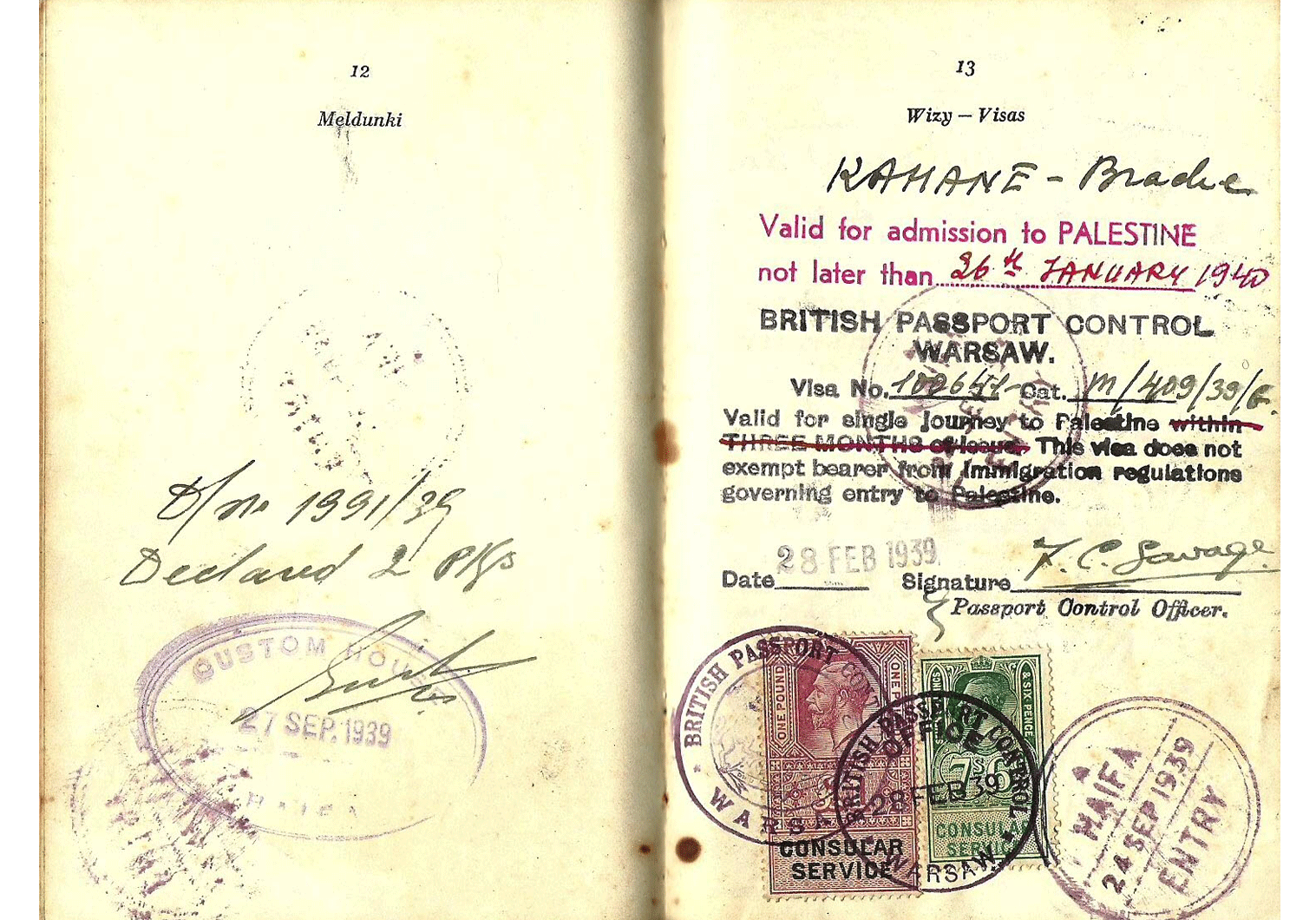

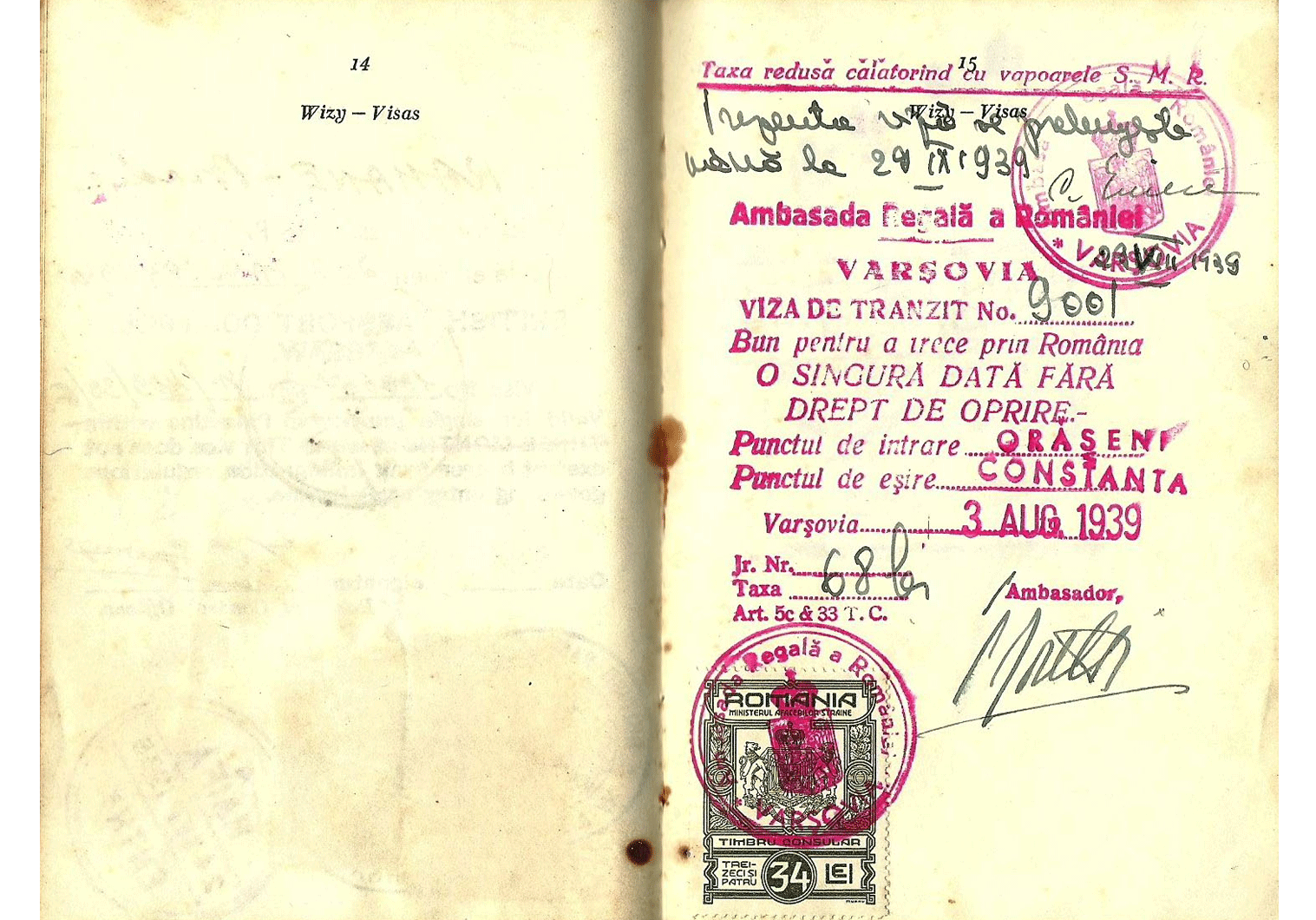

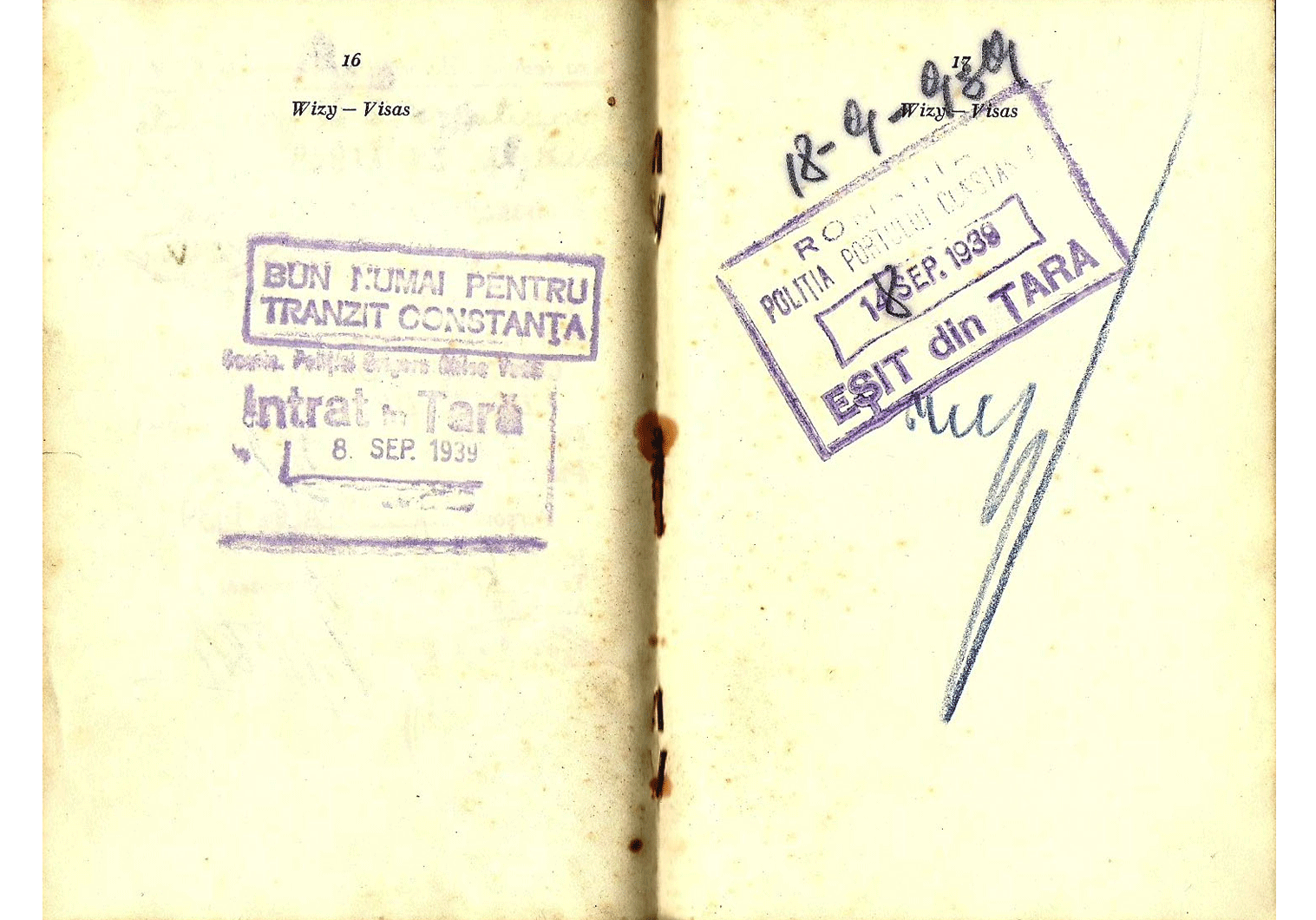

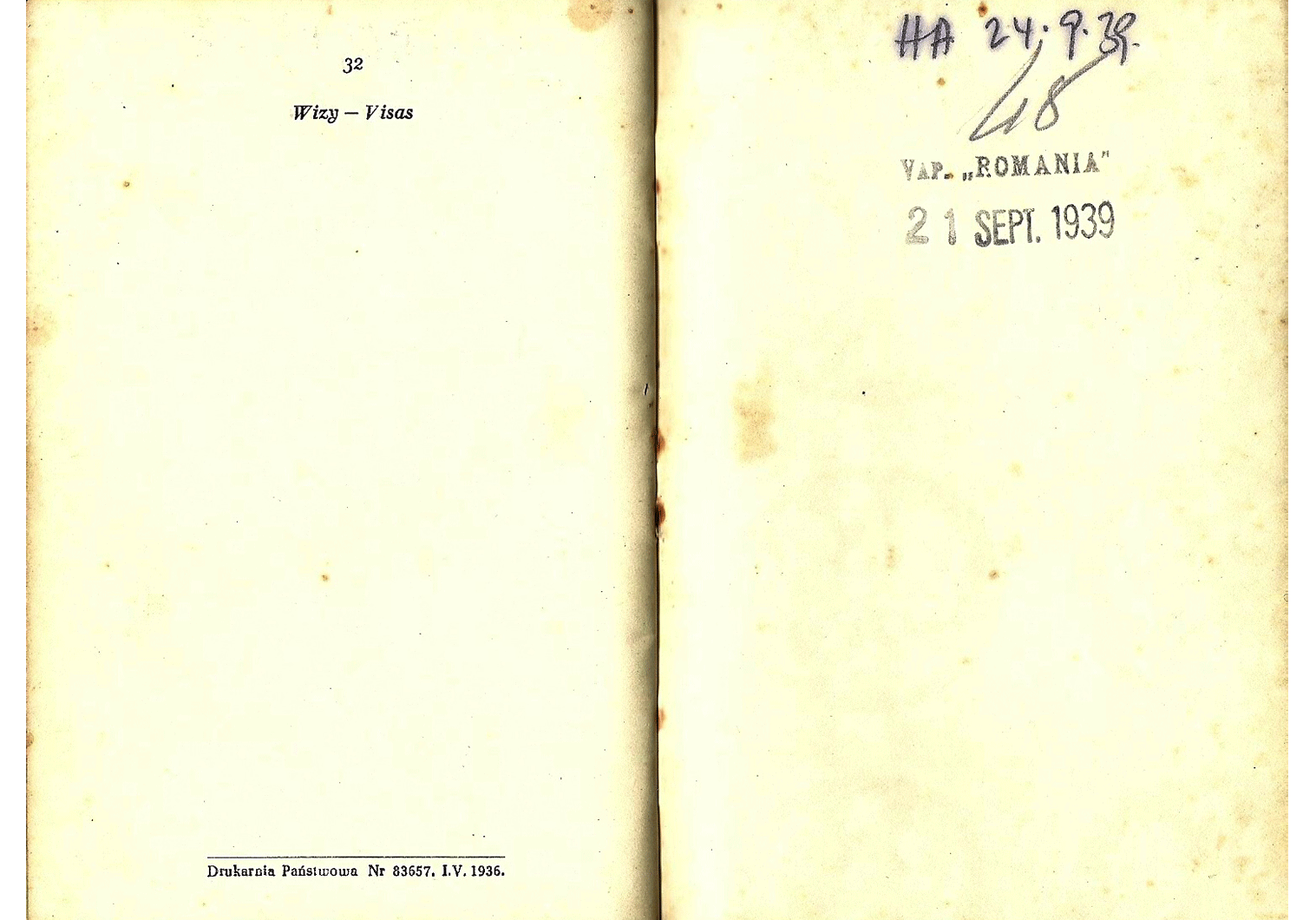

Brache obtained her British Mandate visa from the consulate at Warsaw on February 28th 1939, followed by the Romanian transit visa from August 5th (entry point at the Polish-Romanian border crossing of Oraseni and exiting at the port harbor of Constanta), valid to September 29th. She exited on September 6th, close to week after the outbreak of war and left for Palestine on the 18th. On September 24th Brache arrived at Haifa port.

Not many were lucky enough as she was. Following the outbreak of war in 1939 and after the German invasion of the USSR less than 2 years later, European Jewry would face its most severe crisis in all its years of living on the continent: the systematic destruction of 6 million people during a period of over 4 years, that would practically decimate centuries of history and a thriving culture.

Thank you for reading “Our Passports”.