Fleeing the Soviet Union during the war

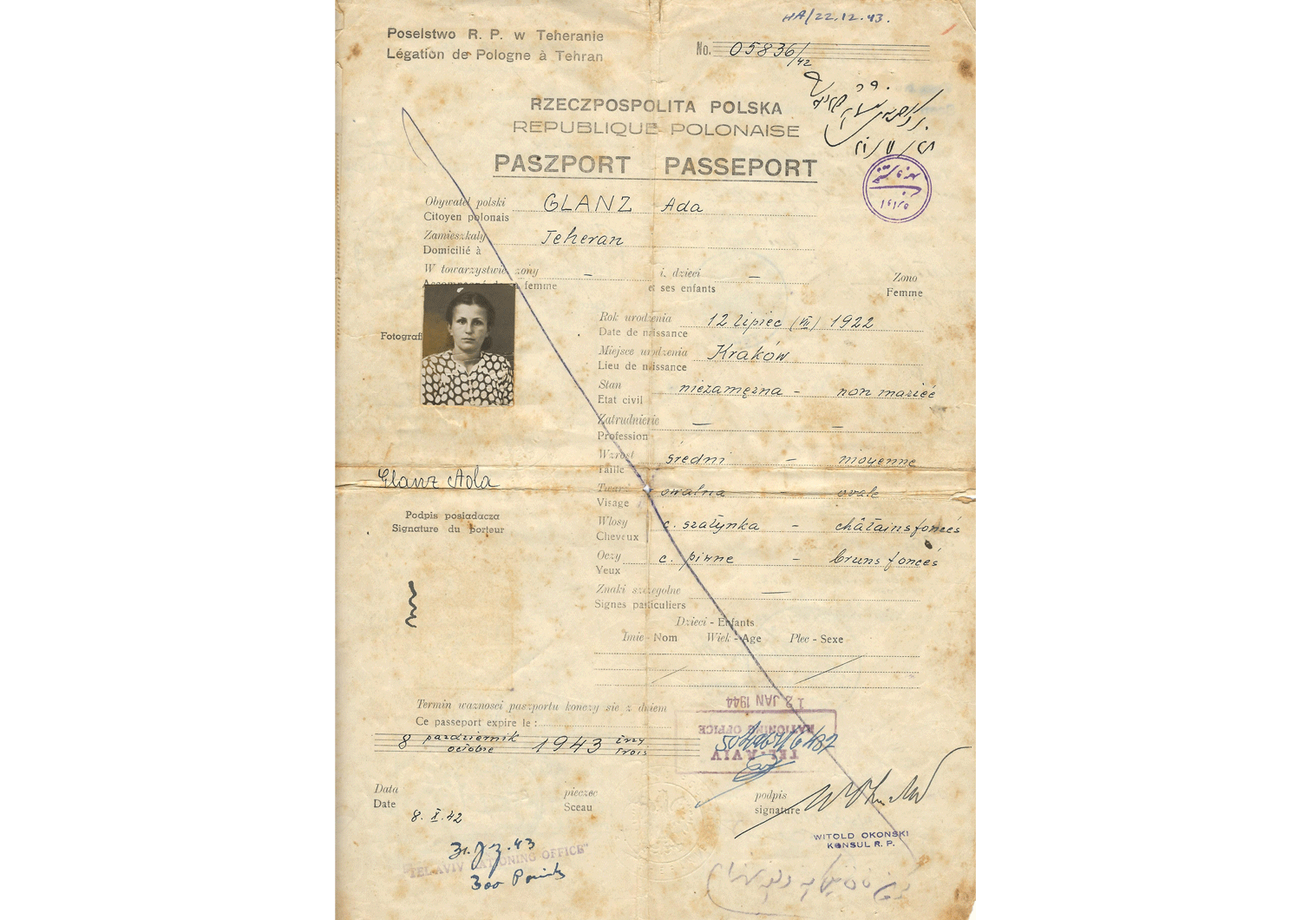

WW2 issued refugee passport from Tehran.

During World War Two countless of refugees sought refuge in Allied and neutral countries; and some even managed to find a safe haven as far away as in India.

Polish refugees began to flee their country in 1939, following the German onslaught on their country. For a period of several weeks, until the Soviet army smashed through their eastern border on September 17th, thousands fled into neighboring Romania and Hungary, in a desperate attempt to avoid the hostilities.

Less than 2 years later, they found themselves fleeing again, to avoid another German onslaught, and this time, a much dire one it was. A massive influx of refugees fled from former eastern Poland into the Soviet Union in 1941, following the German invasion notoriously known as Operation Barbarossa. But already before the invasion, thousands of Poles were forced out of their villages, towns, and cities and deported east, out of occupied Poland (now annexed to the USSR) and those caught as well in the former Baltic States, those who did not manage to escape. Overall 1.7 million Poles were arrested at the beginning of the war. Majority transferred to Siberia and Kazakhstan, placed in Gulag camps, other facilities, deep inside the country. Their position was unclear and seen as enemy of the state. This changed after June of 1941.

The Soviet Union and Poland signed the Sikorski–Mayski agreement on July 30th 1941, after negotiations where conducted between the Soviet Ambassador to the UK, Ivan Mayski and Sikorski. The Soviets where in desperate need for help from other countries opposing Nazi Germany, and this led to the re-establishment of Diplomatic ties between the two, culminating into the singing of the Sikorski–Mayski agreement. Following these events, thousands of civilians and former POW’s were set free from captivity. Such a release led to the re-issuing of new travel documents and passports to those who were now trying to find a way to leave. The issuing of passports where done at the newly established Polish “consulates”, or branch offices, over 20 of them (these where shut down after July 20th of 1942 when the Soviet authorities cancelled their permission to running them), and the type of document can be categorized into mainly 2 types: official passport used to travel outside of the country and a “temporary” passport meant to be used ONLY internally, most likely to enable the holder to reach the border and from there, with other set of papers, to cross over (this was mainly the case with those who managed to be evacuated to neighboring Persia in 1942).

Iran offered temporary housing facilities inside refugee camps that were located around the capital and other locations in the country. The allies contributed immensely with supplies, be it in the form of food or medicine. Many of the new arrivals were in desperate need of such basic necessities. The Polish diplomatic mission in Tehran issued “financial aid booklets”, were the details of the refugees were documented, such as place of birth, date of birth, occupation, passport used and issued for arriving into Iran, financial aid such as commodities or cash were also logged inside the document for record and follow up.

One such individual was a Jewish woman named Ada Glanz, aged 20 originally from Krakow, now under German occupation in what they termed as the General Government.

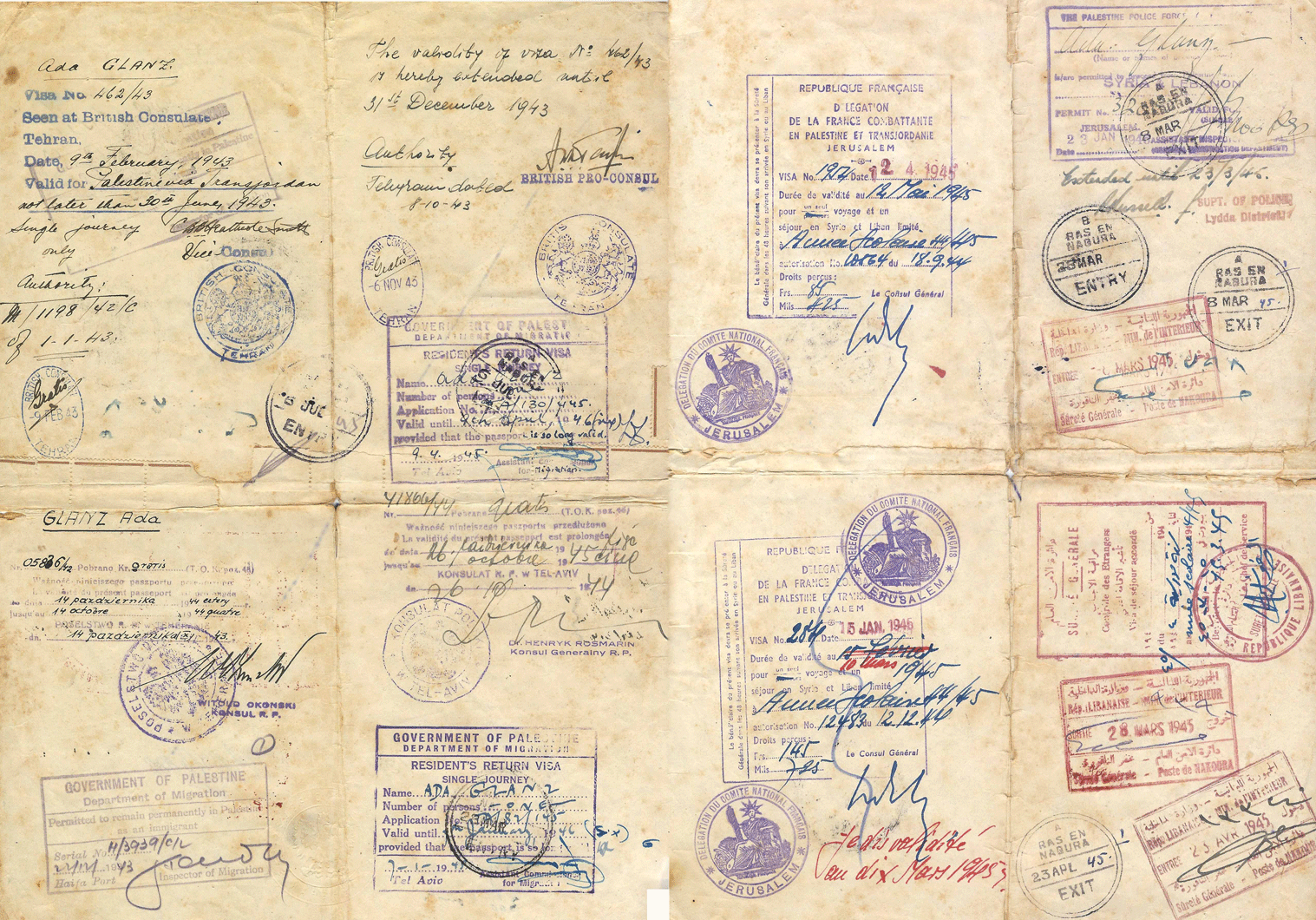

Passport number 05836/42 was issued by the consular service of the embassy at Tehran on October 8th 1942. One year and two and half months later she would arrive in British Palestine, entering the Mandate via the port of Haifa and not originally via British controlled Jordan.

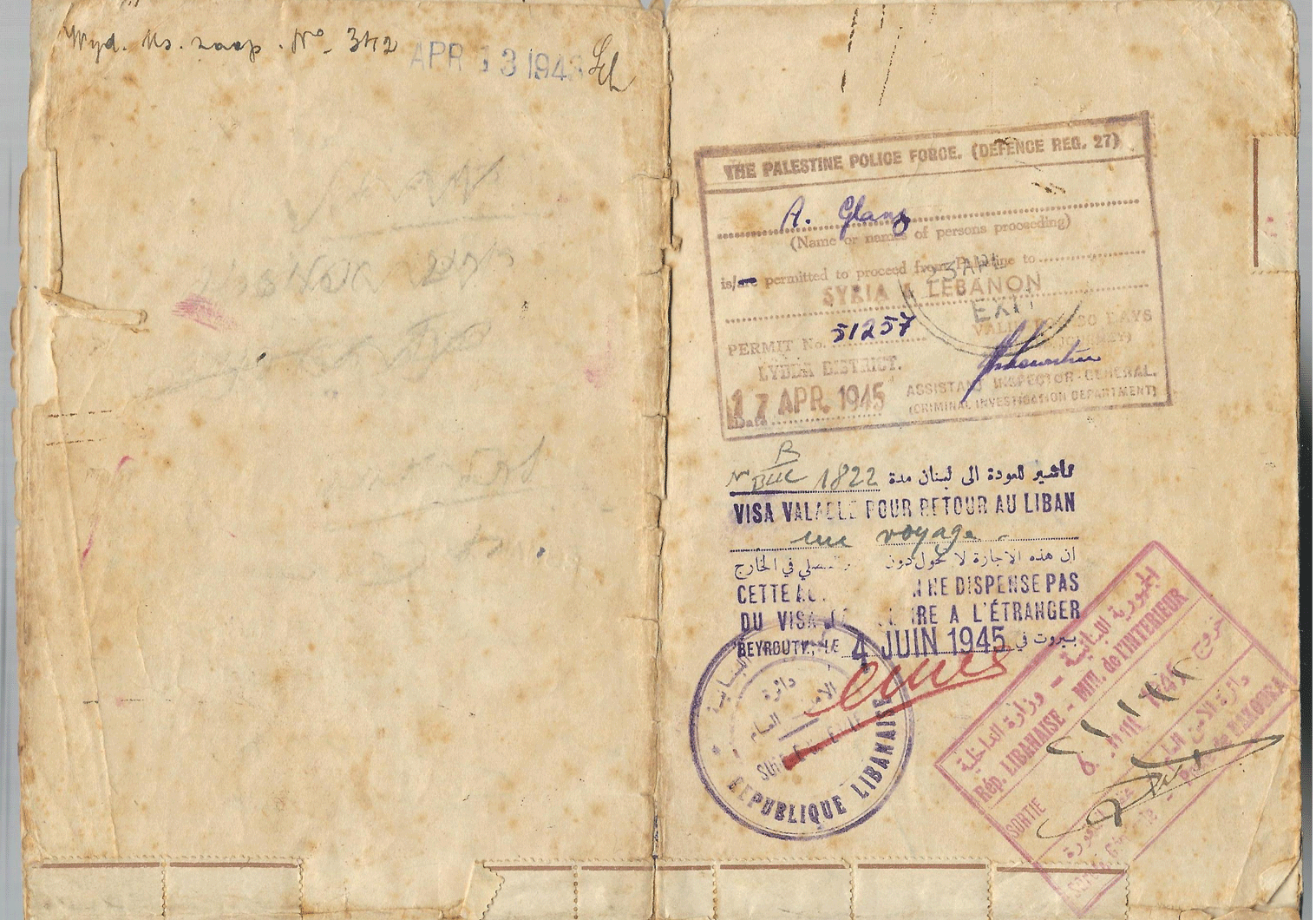

What is more interesting and unique is that her temporary passport was used continuously for the Levant in the Middle East, bearing inside Free French consular visas as well, a pleasant addition to this war-time travel document.

A large portion of the refugees after the war decided not to return to Poland, fearing the new regime that was being formed, after remembering clearly their ordeal in the Soviet Union several years earlier.

Evading the horrors of war and fleeing was not an easy task at all. We learn from the various travel documents that we find that the routes that individuals took at times surpass our wildest imaginations. Today, we at times cannot believe what they went through in order to survive. But the will to live and do so freely is stronger than any cage or prison erected.

I have also added sample images of a passport issued for “travelling” inside the Soviet Union to the border, issued for those being evacuated to Iran; sample image of a financial-booklet issued for the refugees in Tehran and last, another sampled Polish refugee passport issued in 1942.

Thank you for reading “Our Passports”.