Fleeing Poland in 1939

Crossing the border on the last day!

In previous articles, I wrote extensively about the special short period of time that existed, following the outbreak of war, a short-lived “window of opportunity” that enabled thousands of refugees and military personnel, to escape into neighboring Romania and Hungary.

This period of time is very important; not only because of the human lives that were saved from the German and Soviet onslaught that came after the hostilities erupted, but also because it gives historians and collectors important information on the escape routes that were utilized during the war.

In a period of about 16 days, the borders between Poland and her eastern two neighbors were open and thus the migration from the German western side of the country proceeded, first, to the “free” eastern part and then further east to Romania and Hungary. Once in safety, many could eventually apply for the desperately needed passports and temporary travel documents needed for continuing their journey to France and the UK.

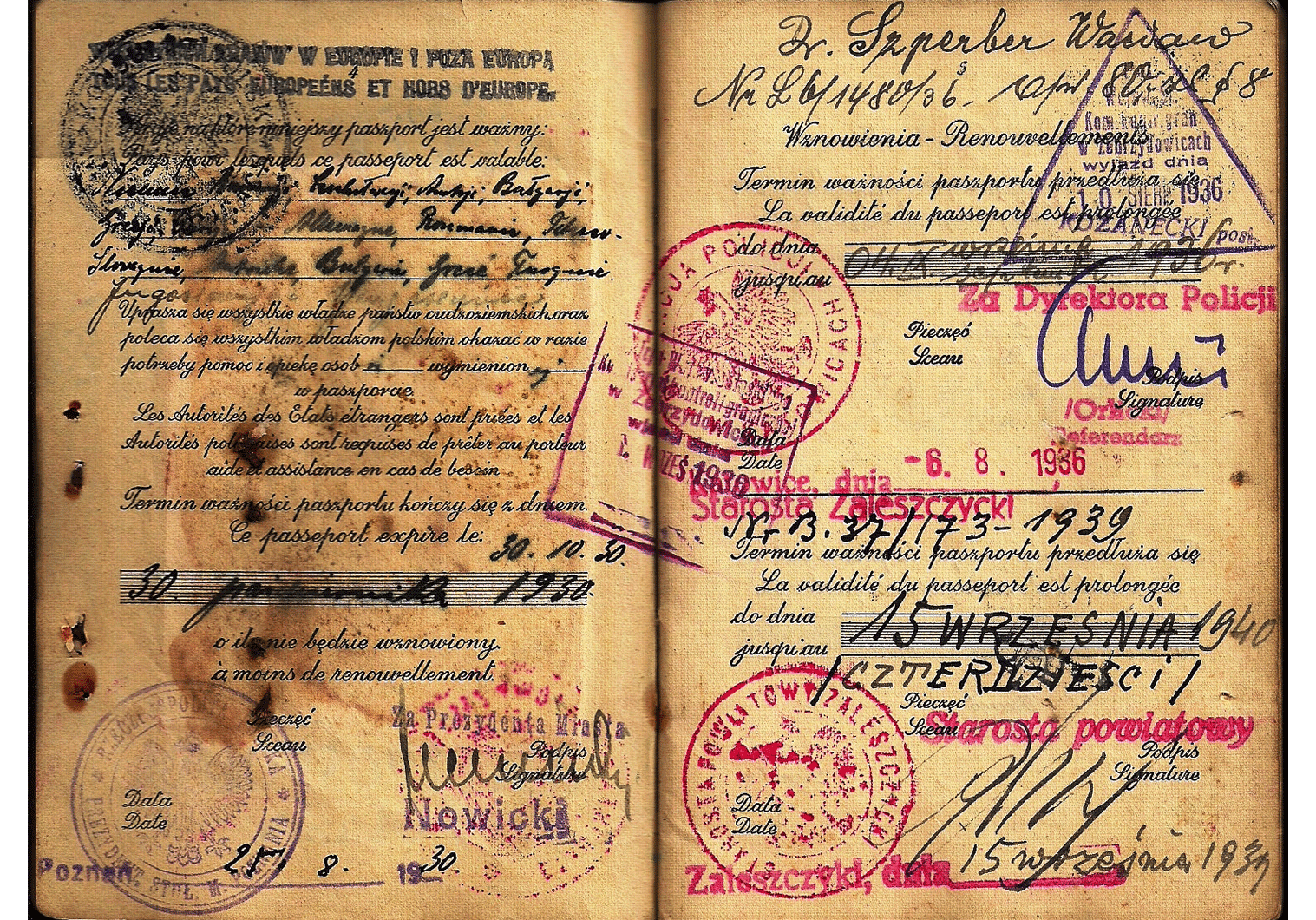

We can find regular blue-jacket covered passports (printing started in 1929 and continued up to the war itself; the first samples were printed in the end of 1929, where as the last Polish printed sampled imprint is for March 1939; and after the war broke out, the French printed them during 1939-1940. After the fall of the country, London became the main printing location for the Polish passports supplied by the Government in Exile. Some diplomatic legations, when running short of passports, resorted to having them printed locally, for example, in Berne, Switzerland) being the first to be issued during the first week or so following the invasion, but this quickly changed to large A4 sized folding passports that were printed locally in Bucharest & Budapest. Even office-typed sheets were found to have been issued by the consulate at Cernăuți, today in Western Ukraine but up to 1945 was part of Romania. At the end, according to some witness testimonials, the diplomatic missions resulted in even issuing forged passports for both civilian and army usage: the diplomats were working around the clock in saving as many civilians as possible, before the closing of the borders and also in the swift evacuation of the Polish army, that managed to escape safely, to western Europe where a new army was being formed in France.

The passport in this article is a pre-war issued passport that was used again in 1939 for escaping to Romania, together with the holder’s son.

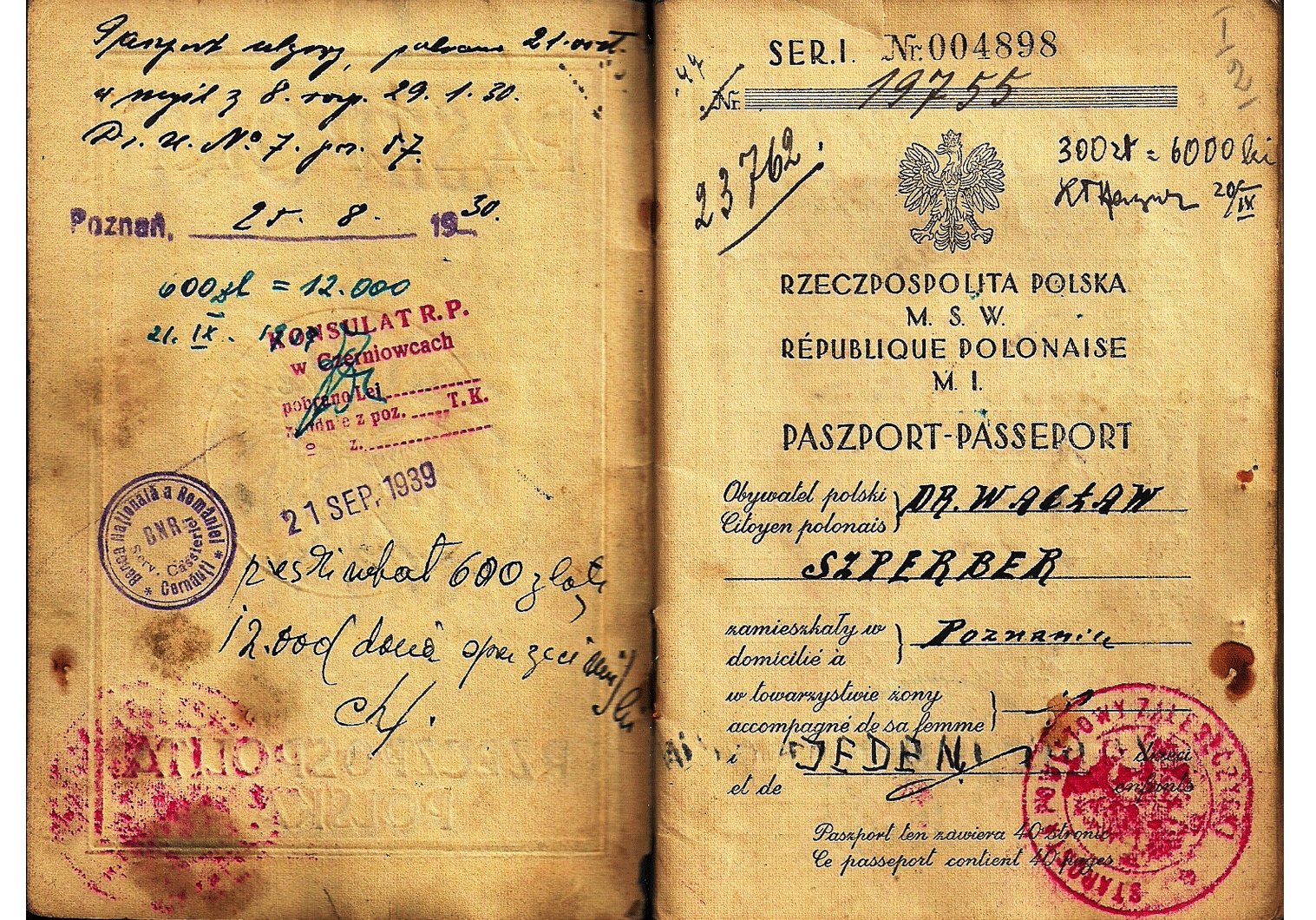

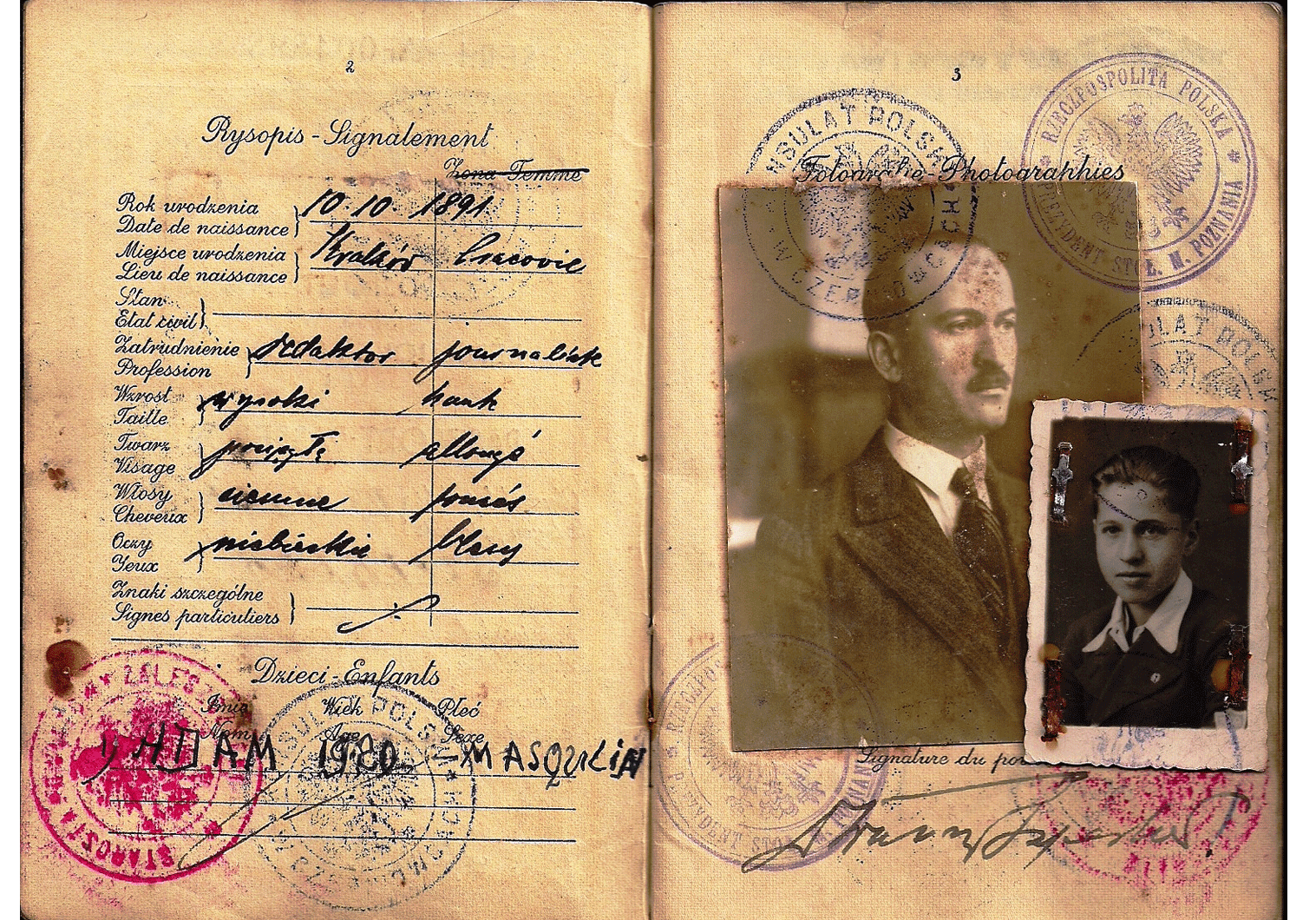

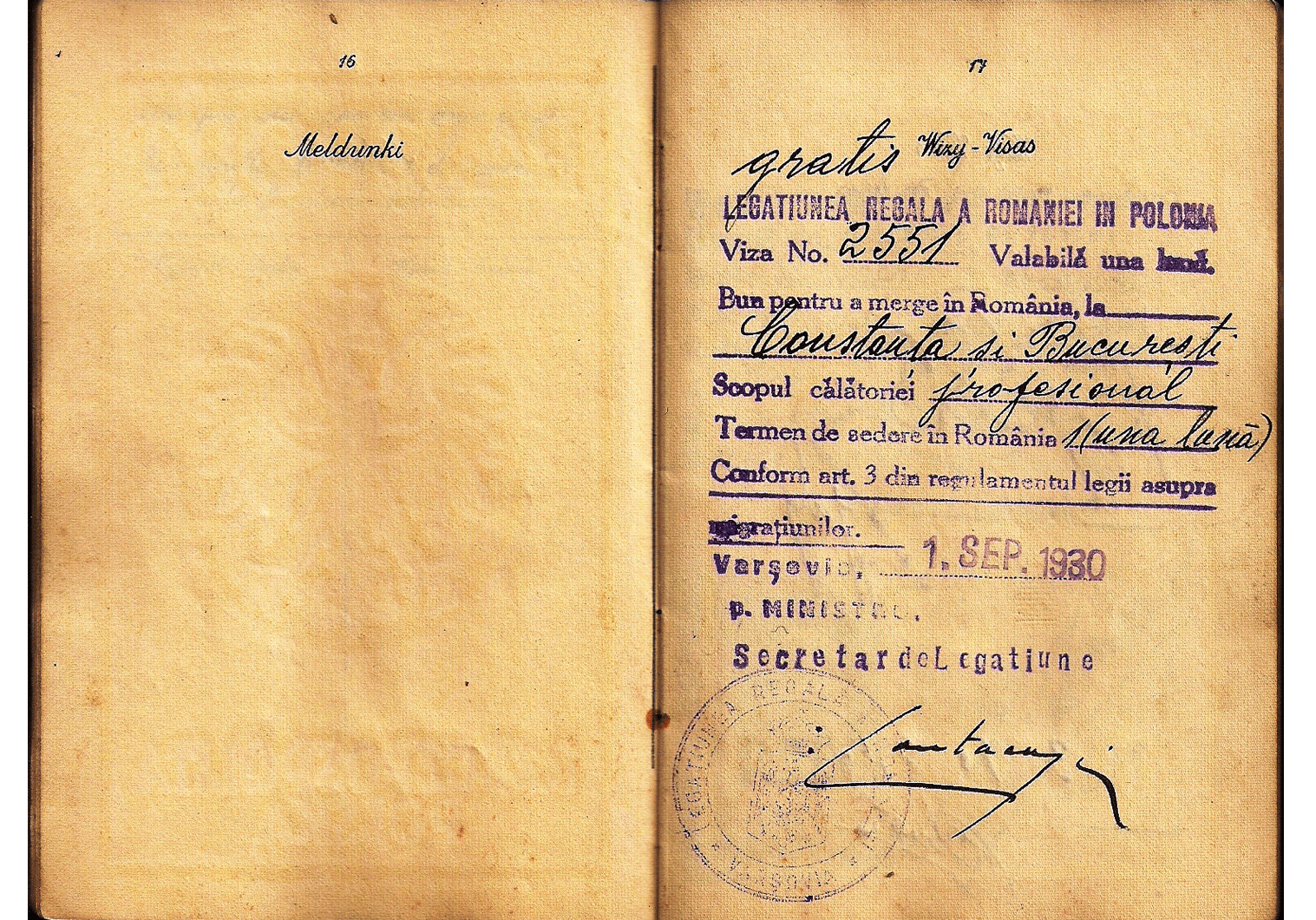

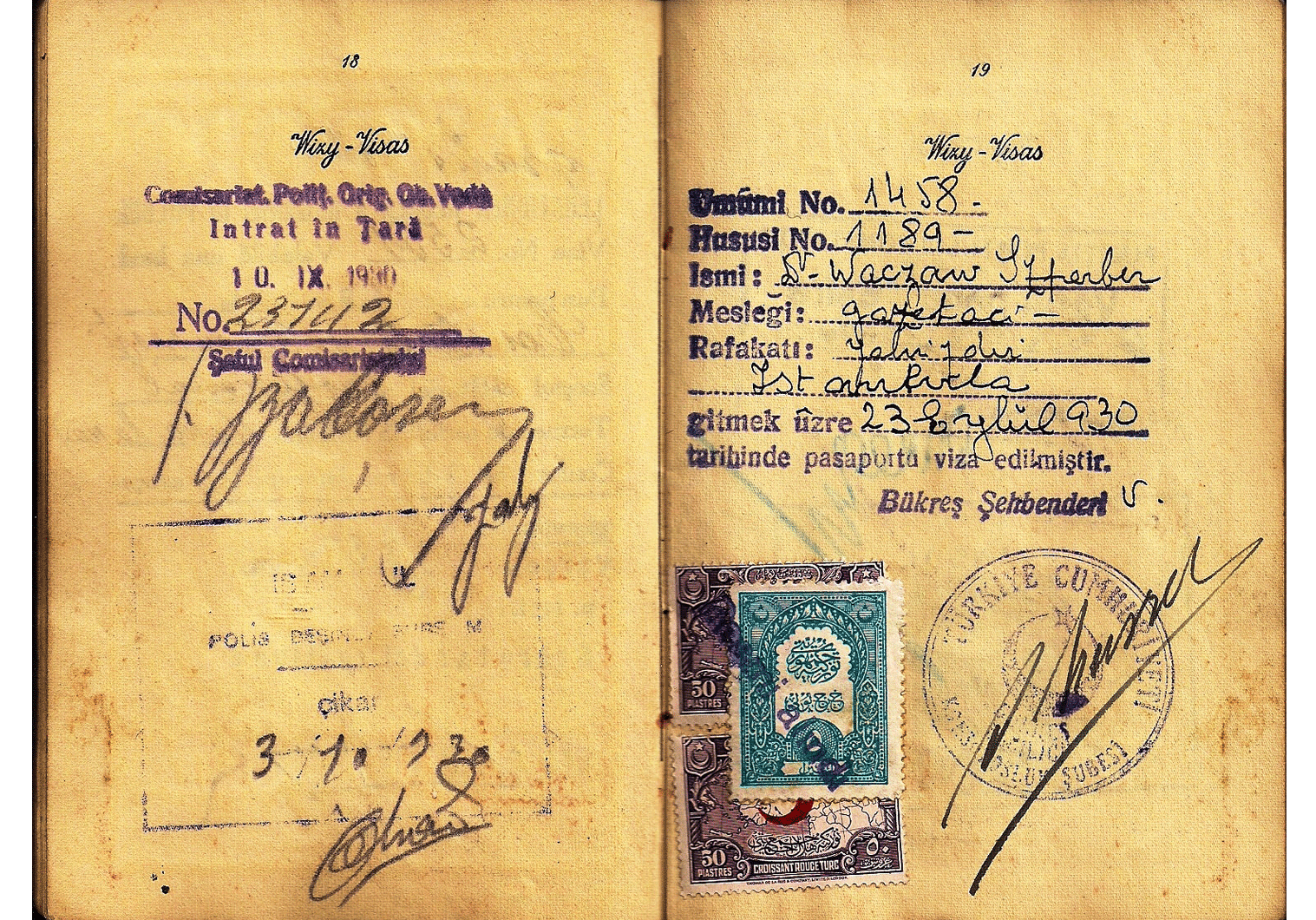

Travel document number 47/19755 was issued to Dr. Waclaw Szperber (1891-1960) on August 25th 1930 at Poznan, western Poland. The passport was used for traveling abroad on work and on some occasions on official visits abroad (page 17). His work is stated as being a journalist (he was also a captain of infantry in reserve). He in fact was a doctor of legal sciences and working also for some time at the “Illustrowany Kurier Codzienny” (“Illustrated Daily News”). An interesting addition to his career is that in 1931, in Poznan, he was awarded by the Greek Government with the Order of the Savior, and the award was presented to him by the Greek Consul Doctor Stanislaw Slawski. It is important to add that the war years he spent in London, since some of his publications where printed there as early as 1942.

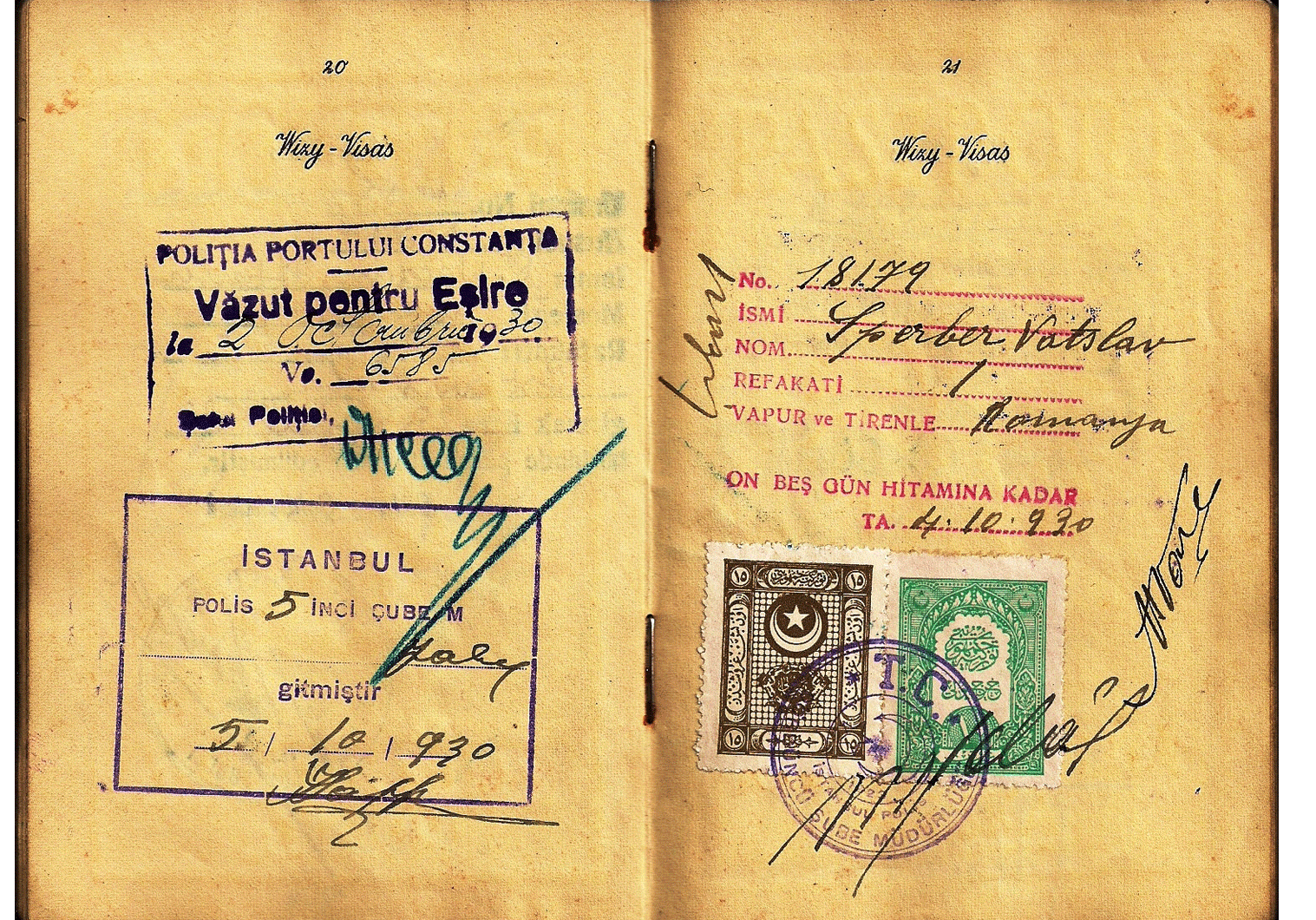

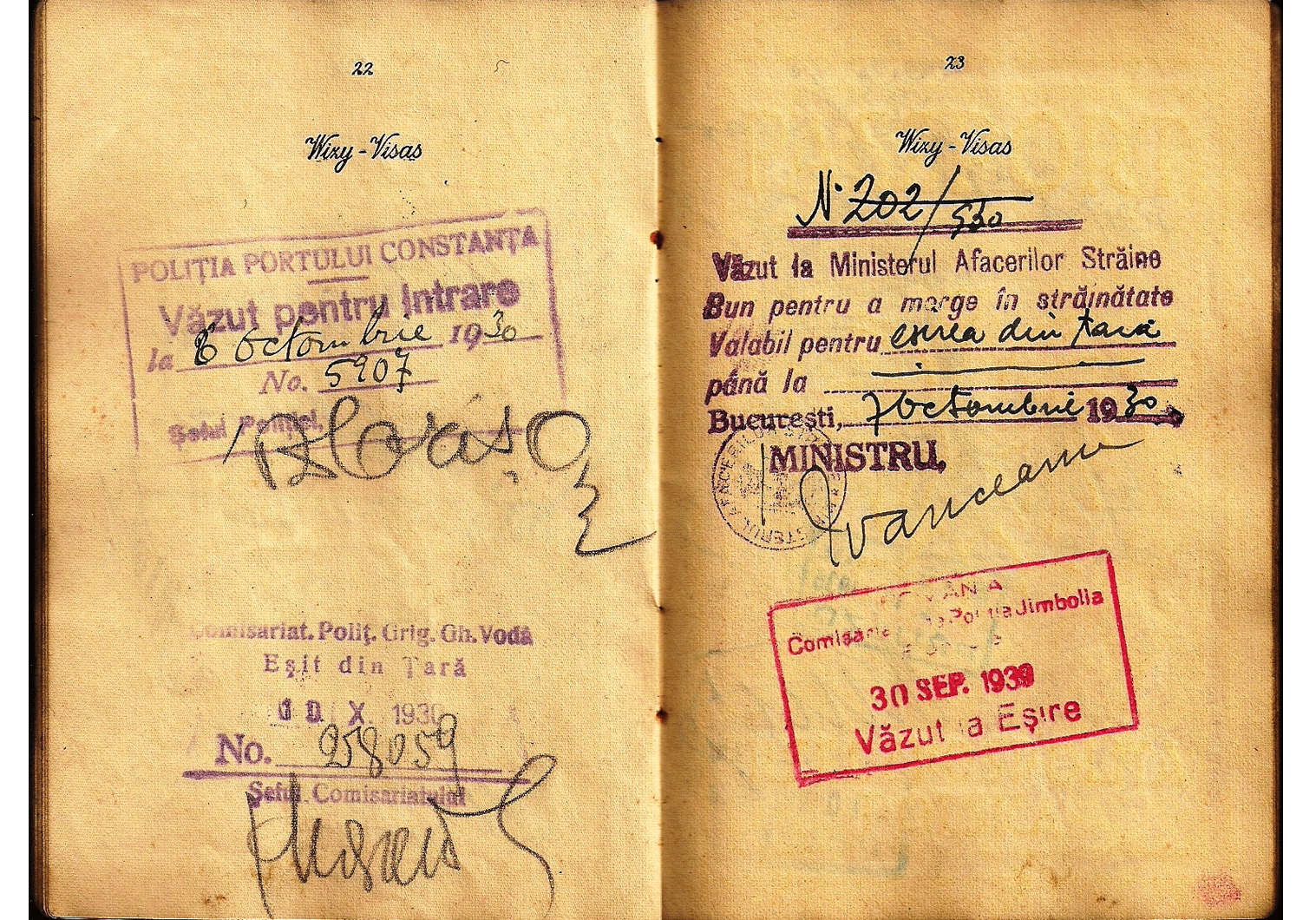

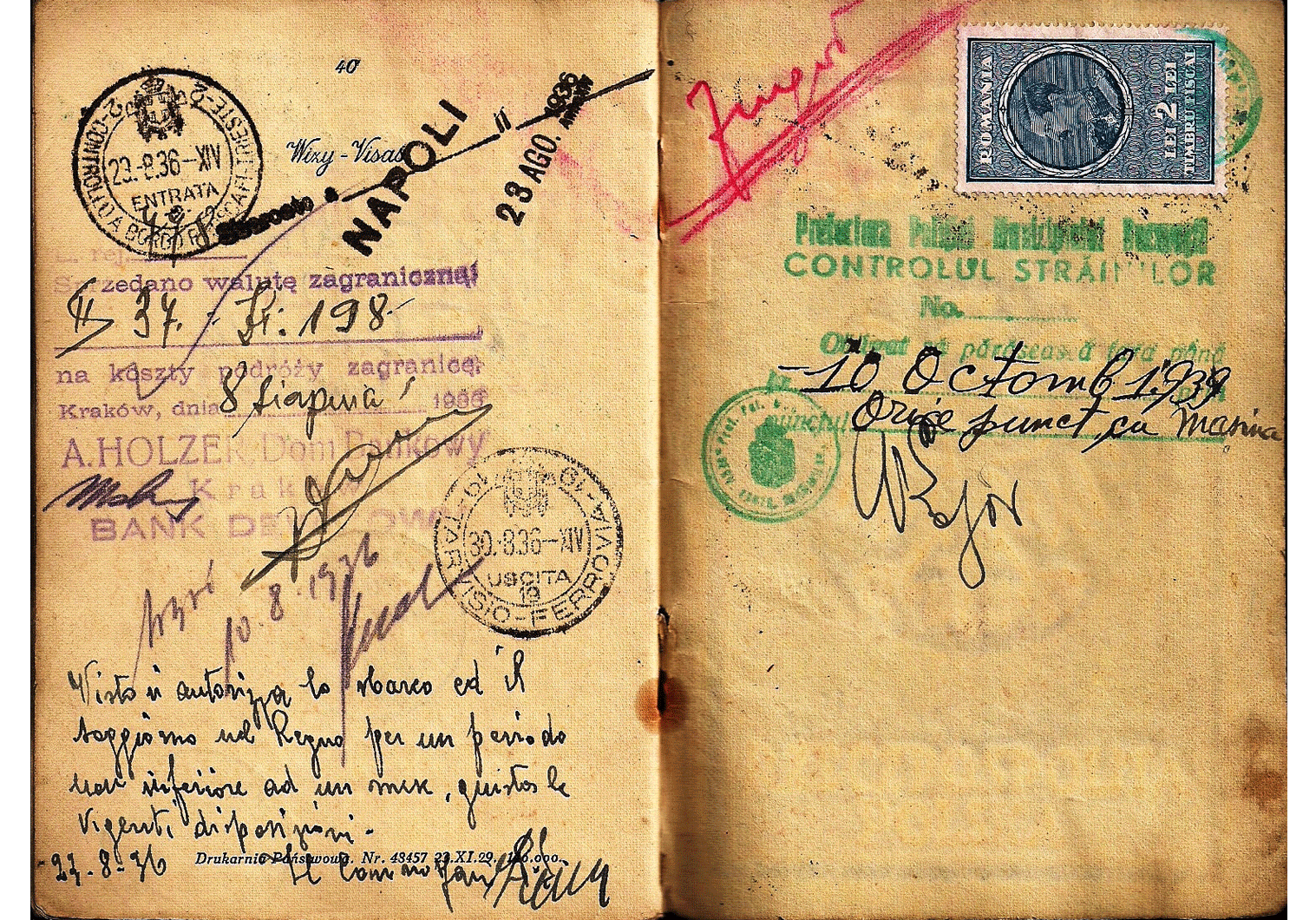

The passport has pre-war visas for Romania, 1930, where he went on official consular affairs in Bucharest. Same year took him to Turkey as well.

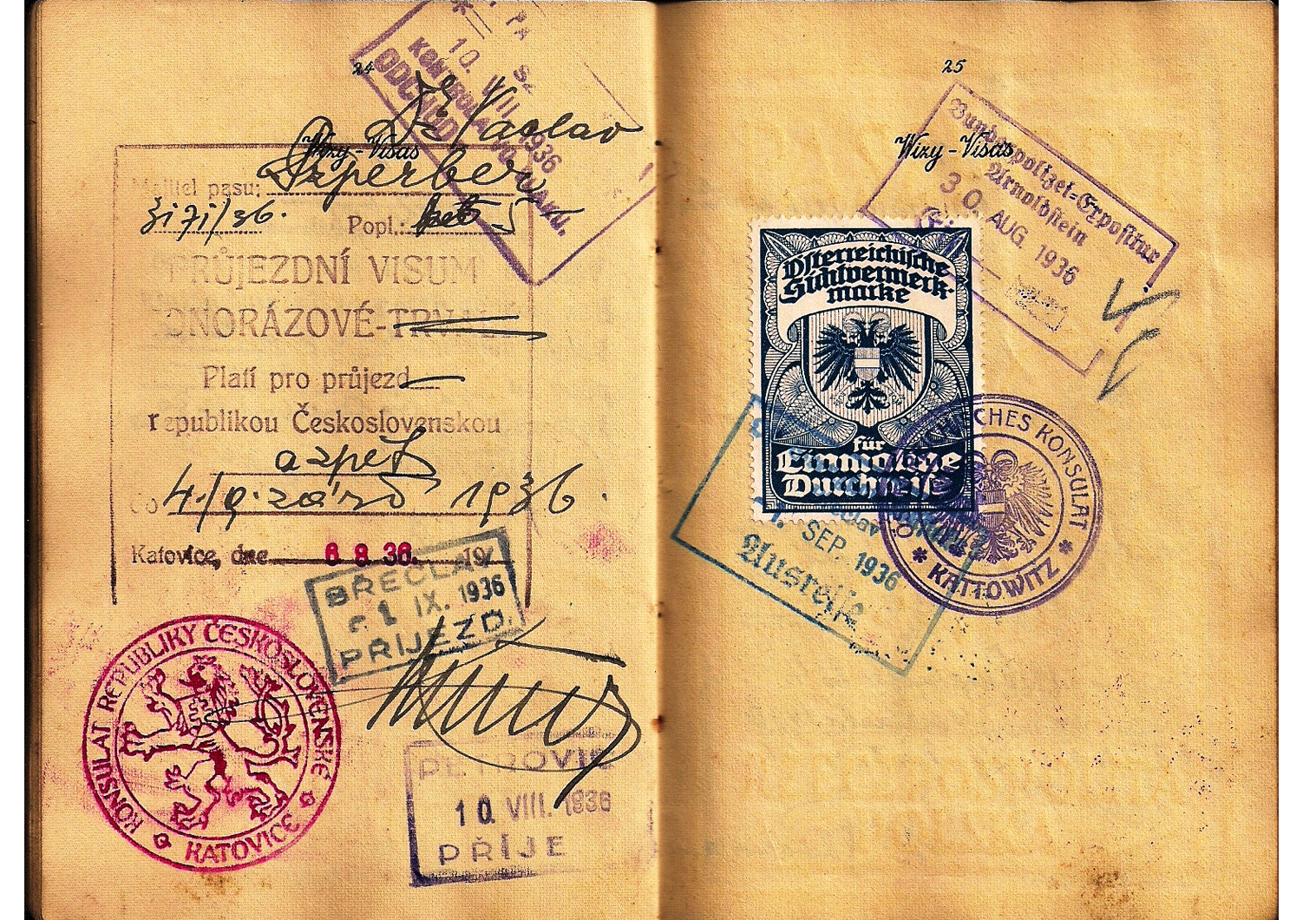

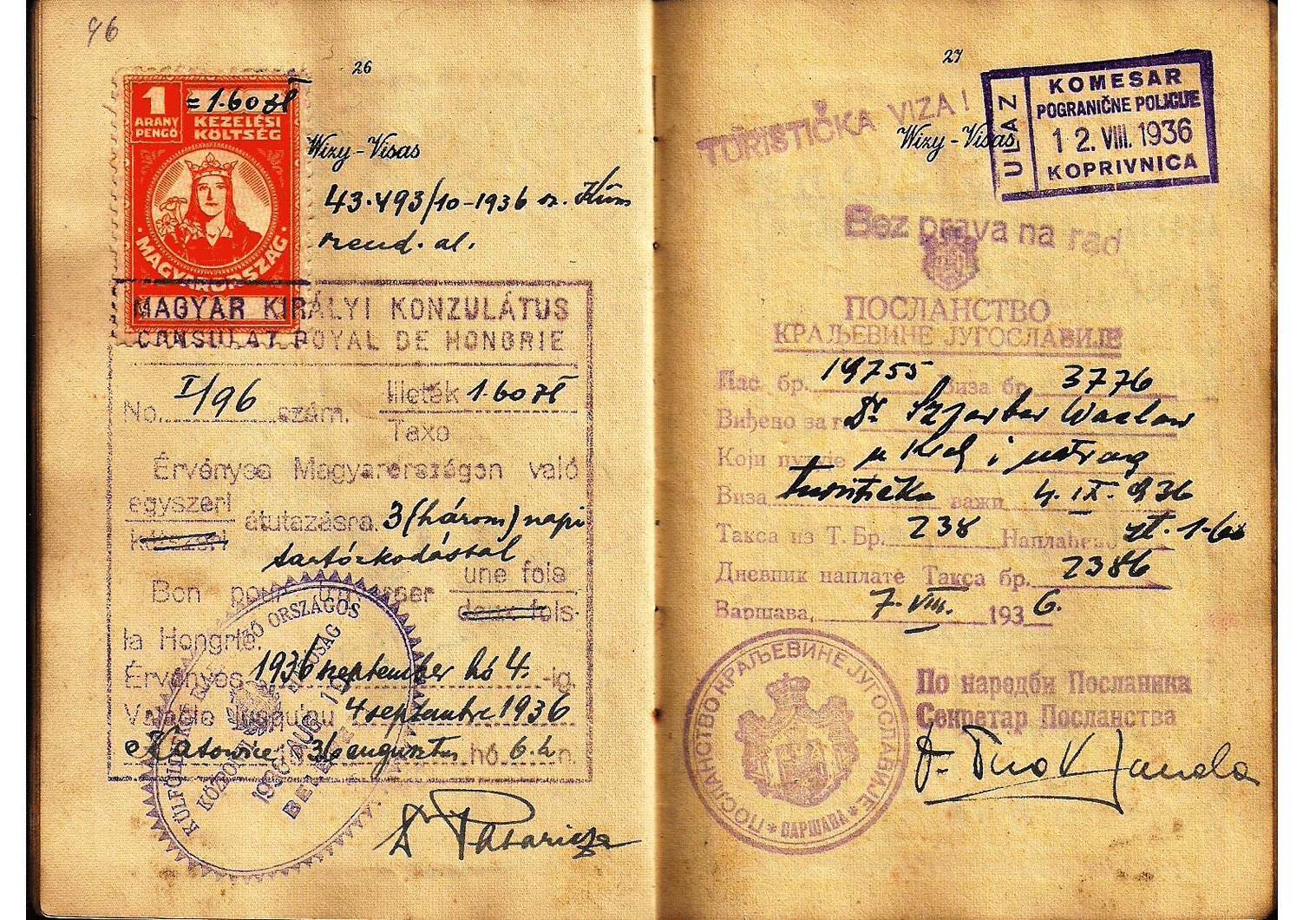

1936 was the next usage for trips to both Hungary and Czechoslovakia.

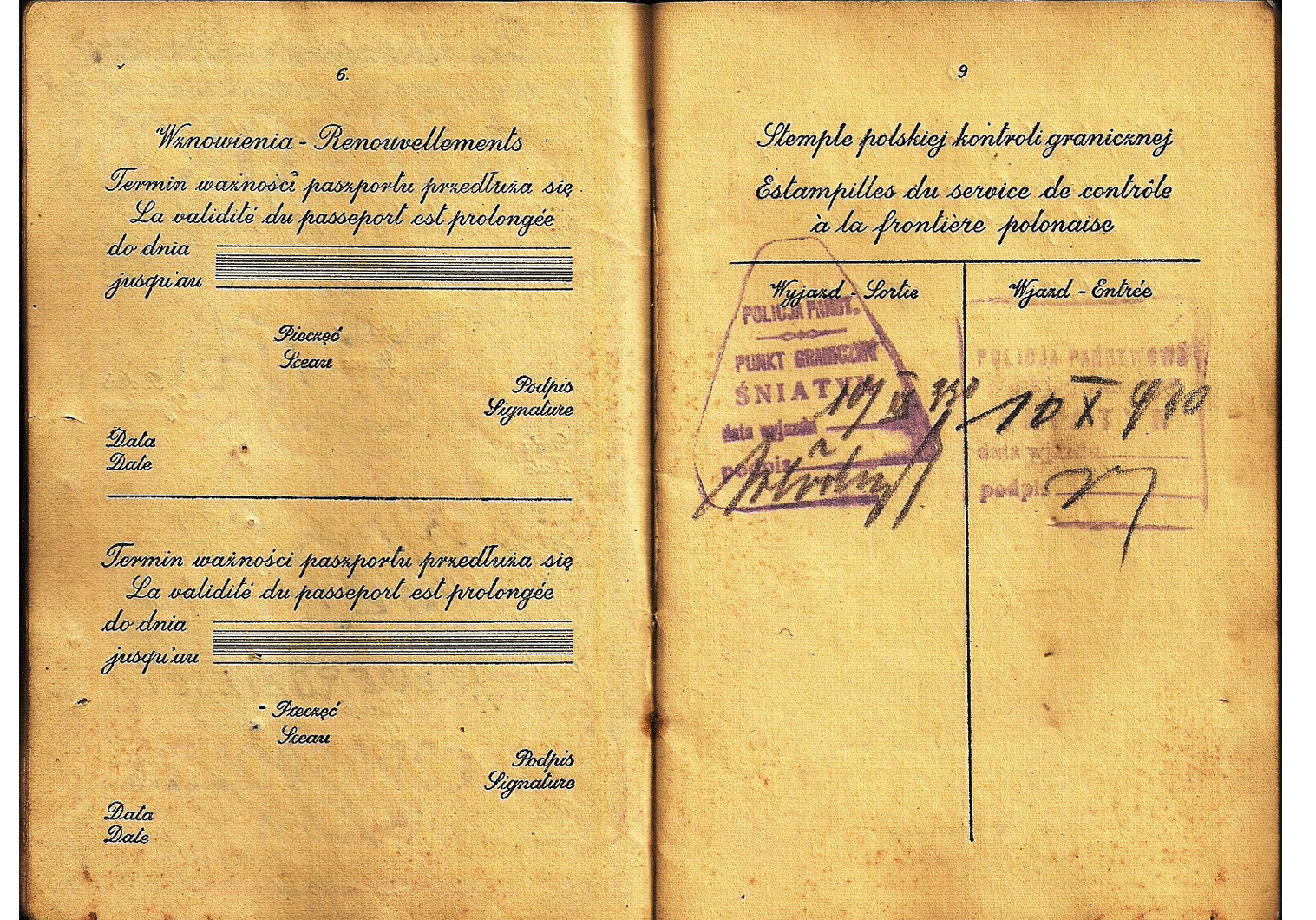

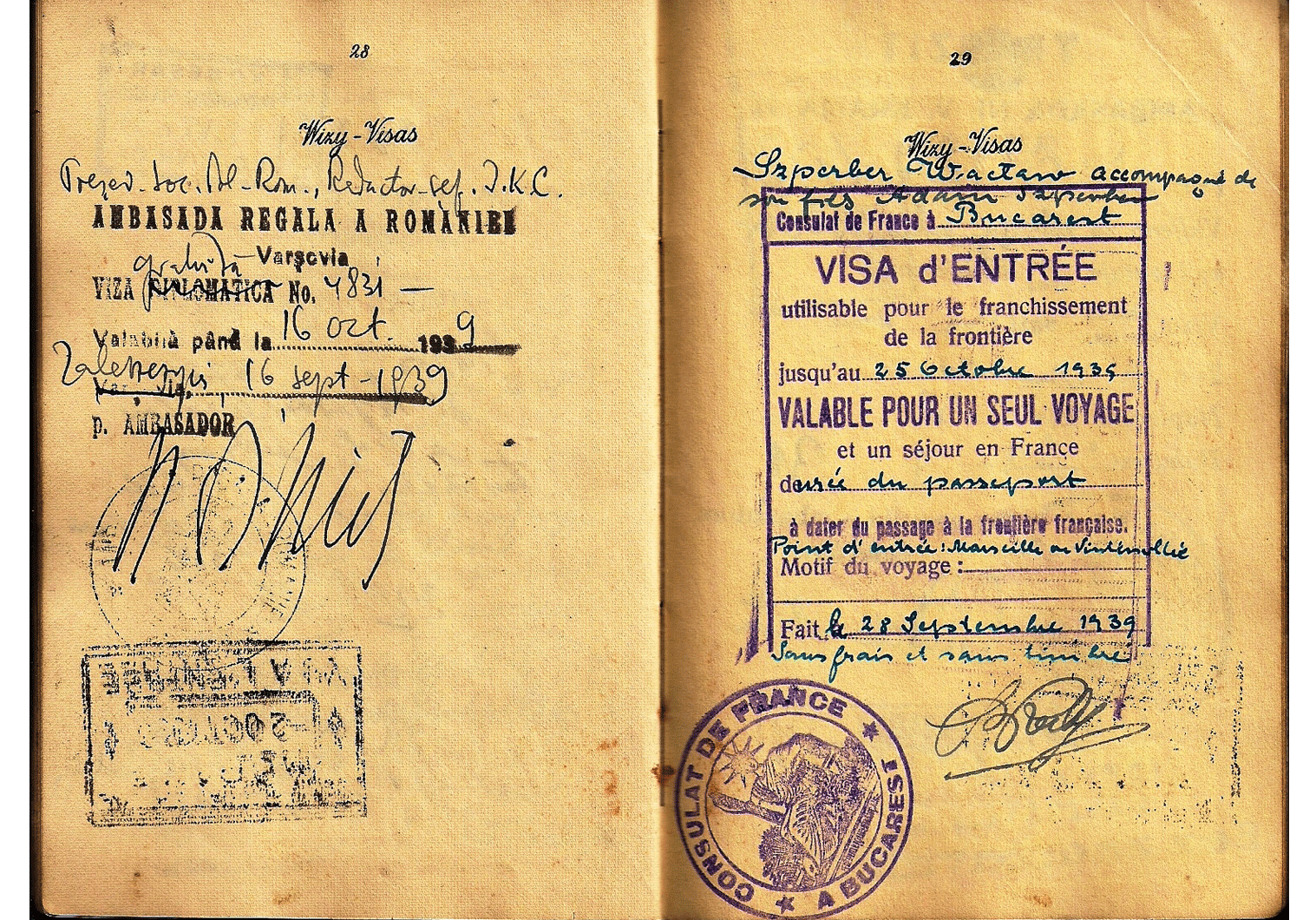

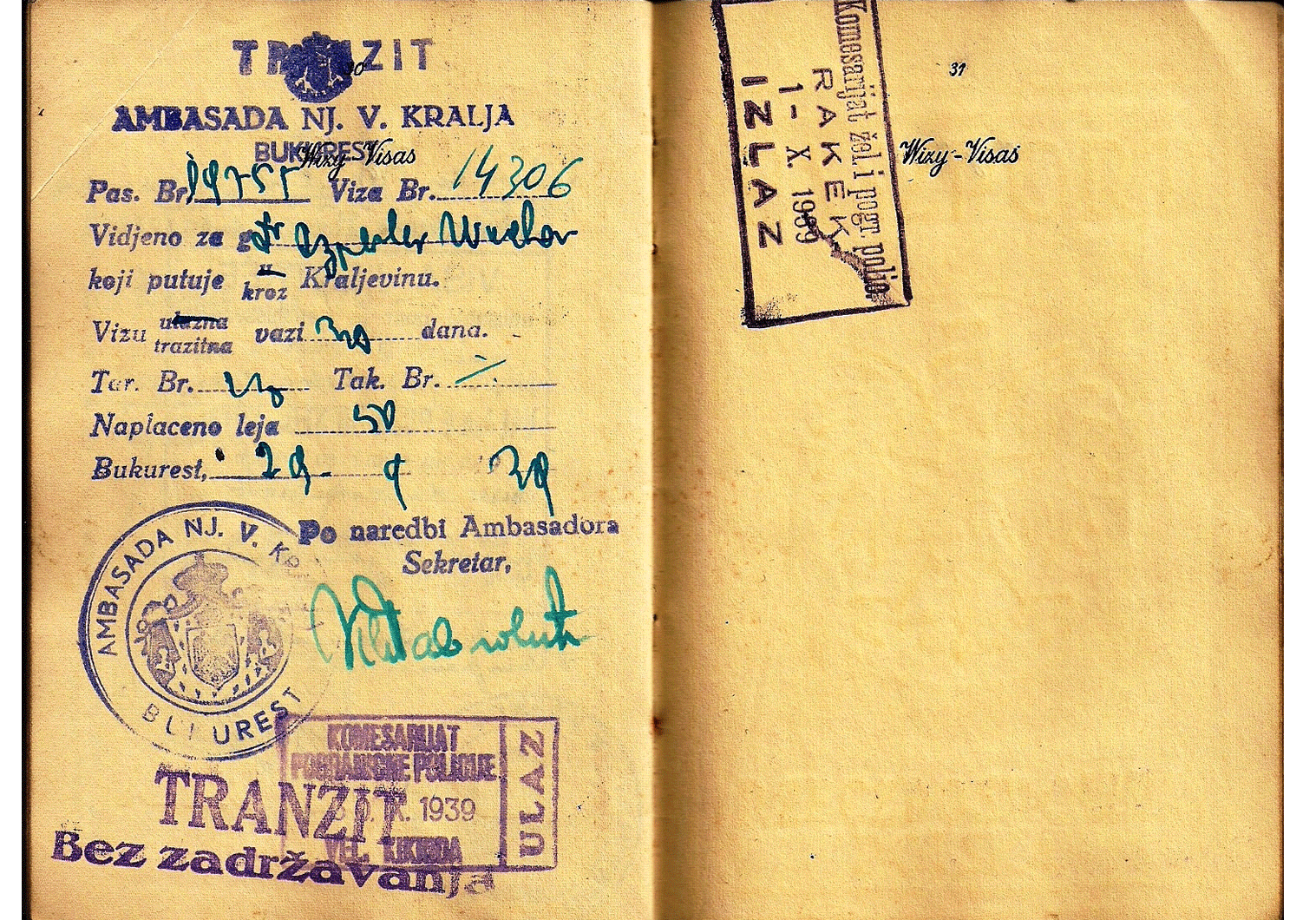

The next, and the last time the passport was used was in 1939: he had it extended on September 15 at Zalishchyky. This is an interesting location: it was a border town located close to Romania. Next, he had a Romanian GRATIS entry visa, number 4831, applied at the same town, where the embassy was evacuated to earlier in the month. The visa is dated September 16th (!), a day before the Red Army’s invasion from the east that took place on the 17th. The timing was just perfect, sadly, under the circumstances.

The passport was amended to include his 20 year old son Adam; this was done after arriving to the polish consulate at Cernăuți, as seen on page 2.

Once in safety and away from harm’s way, the visas for France and other transit countries where applied for: the French visa from September 28th and the Yugoslavian visa from the 29th.

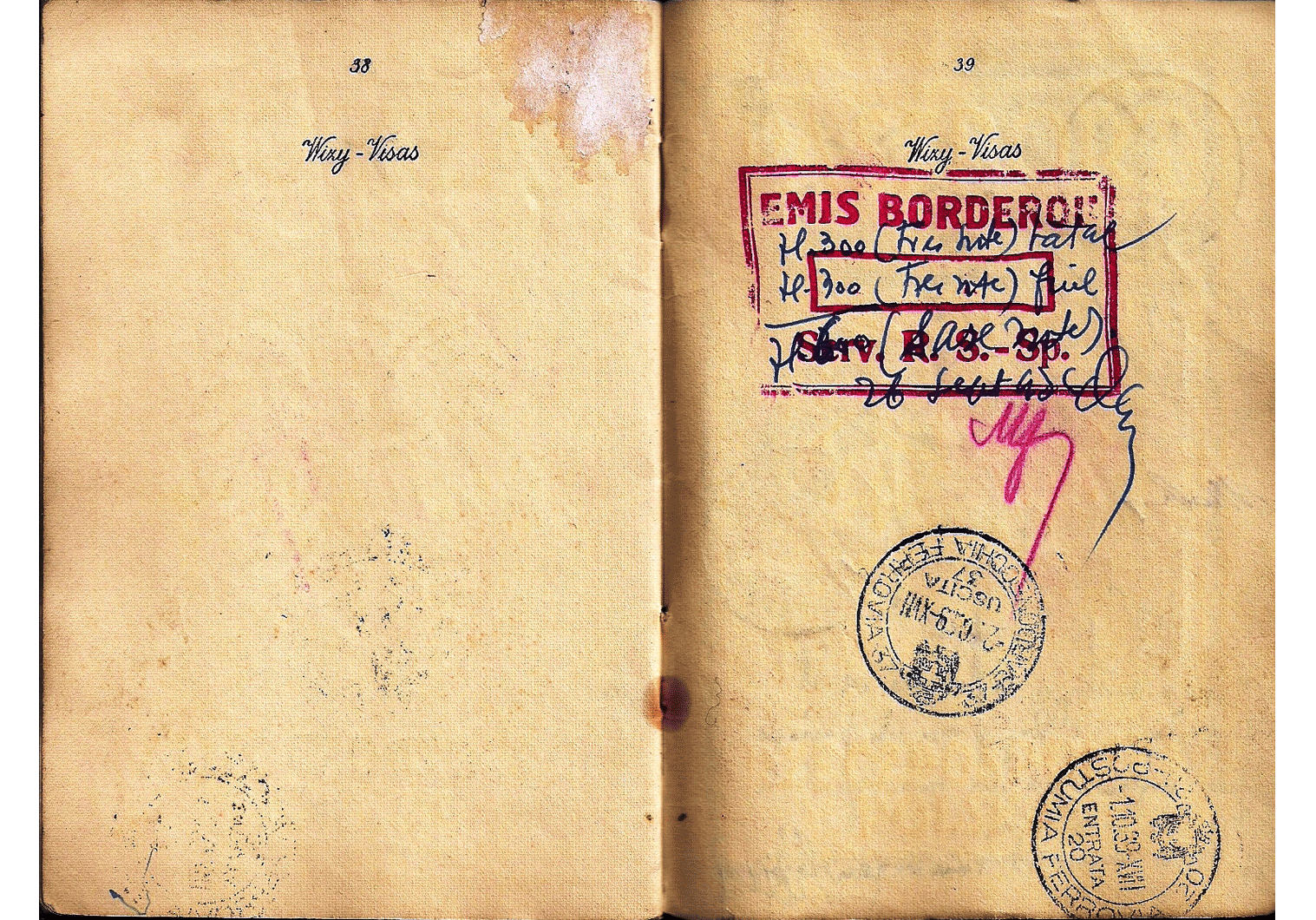

They both arrived at the south French city of Modane on October 2nd, after transiting through Italy on the 1st and Yugoslavia a day earlier.

According to some on-line information, Adam could have been fighting with the Allies and was killed in action on October 1944 in Belgium, but to date could not verify this yet.

The strongest will is the one to survive, continue living and thrive. Such passports are an important reminder of what one can achieve, sometimes when all the odds are against you, when one is fighting to survive and find refuge. The routes that are now documented inside each passport tell us the fascinating and almost unbelievable story of the holders past.

Thank you for reading “Our Passports”.