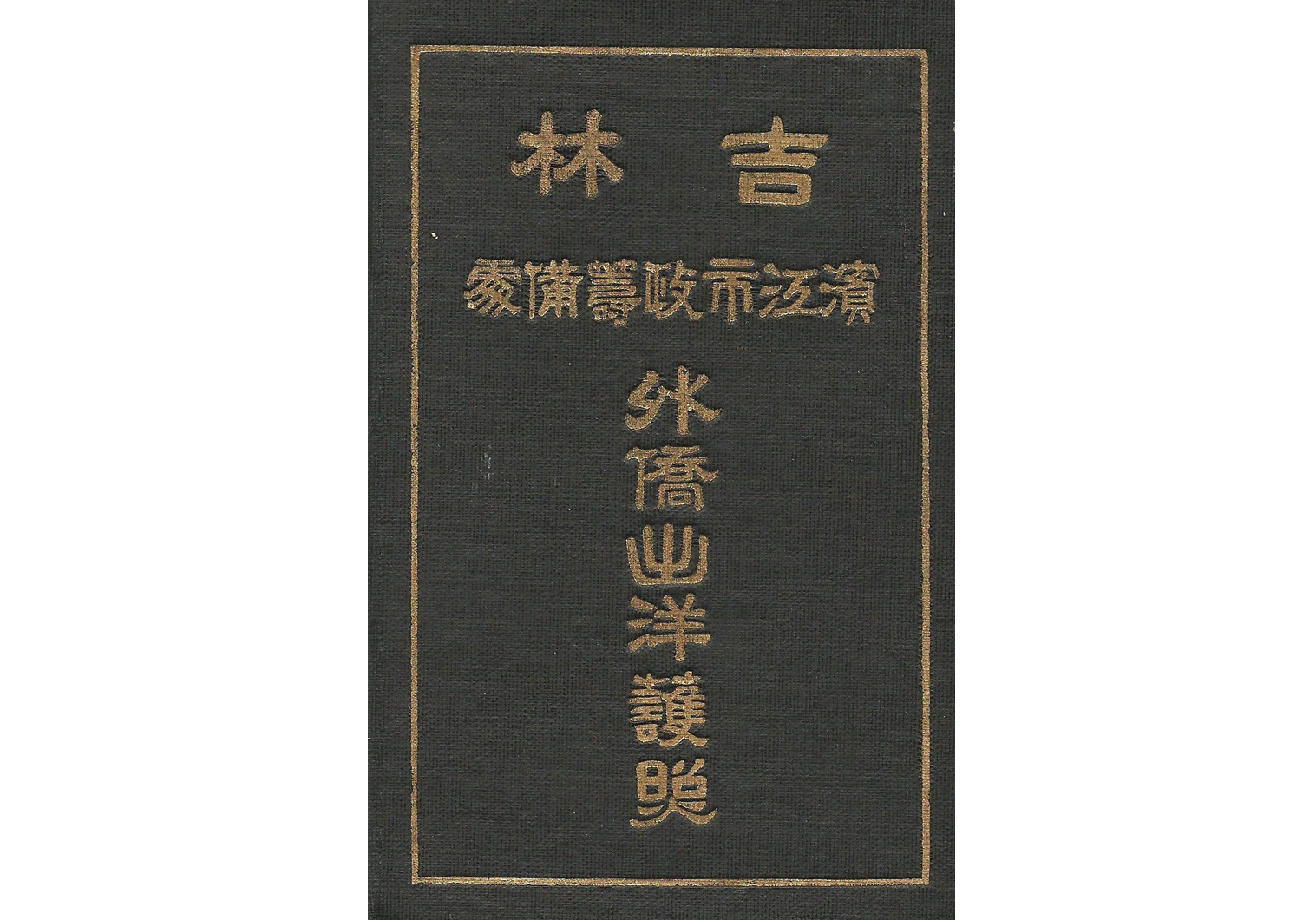

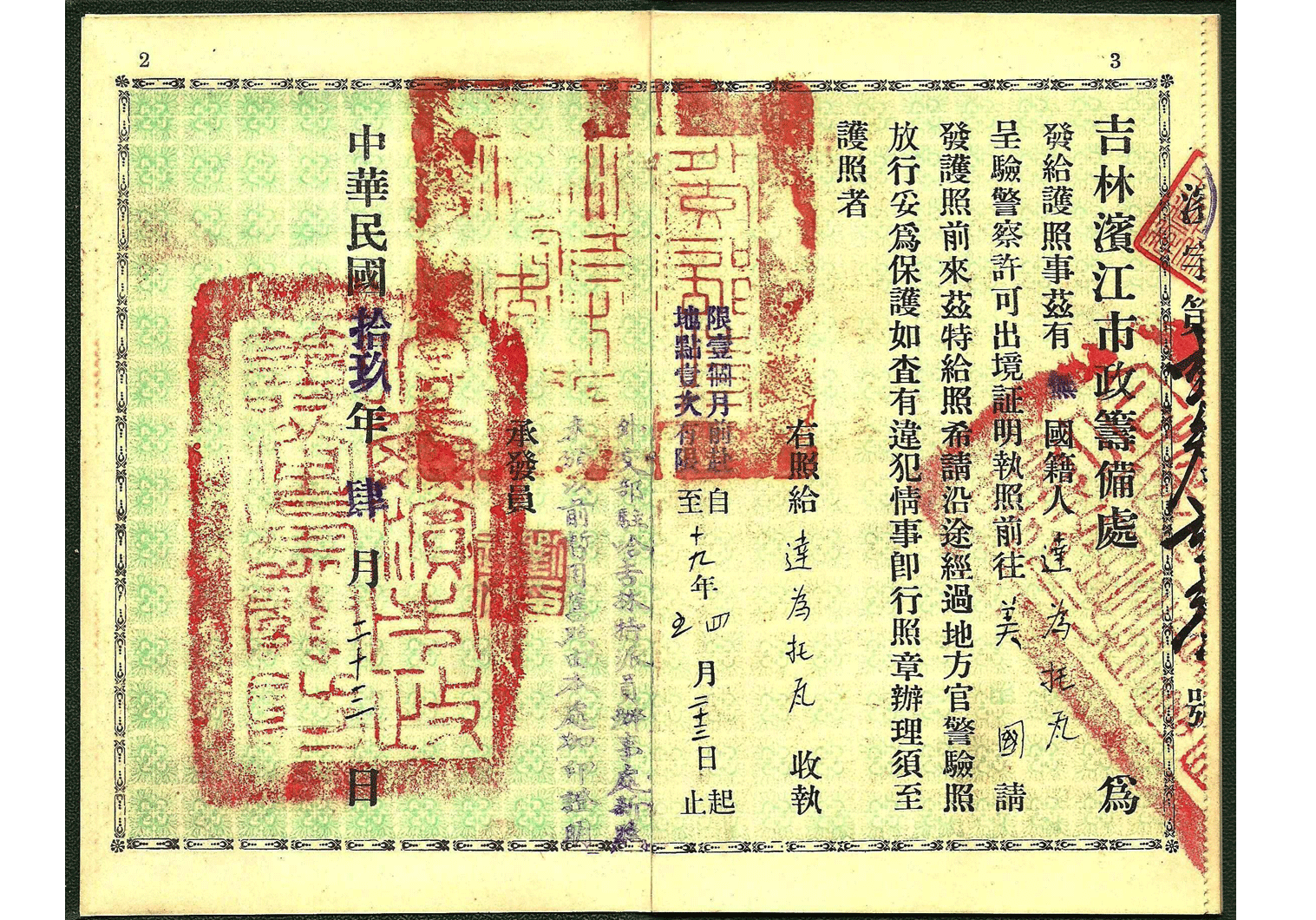

Early pre-occupation Manchurian passport

Harbin issued travel document – Shortly before the Japanese occupation.

1930 was the last year before the Japanese would occupy North-Eastern China in what they would term it as the Mukden Incident and the Chinese as full blown invasion.

What would start as a local initiative by the Japanese army in China would escalate to full occupation and the founding of the Manchurian empire shortly afterwards. The event took place near the Chinese city of Mukden (Shenyang 沈阳) on September 18th of 1931 (this date is commemorated today in China with long sirens heard throughout the cities up north) by rogue Japanese army units, led by Lt. Suemori Kawamoto, who tried to derail a train of its tracks, but failed. Yet, the Japanese blamed the incident on the Chinese and launched a full scale invasion. One of the main cities to fall under their control was the North Eastern city of Harbin.

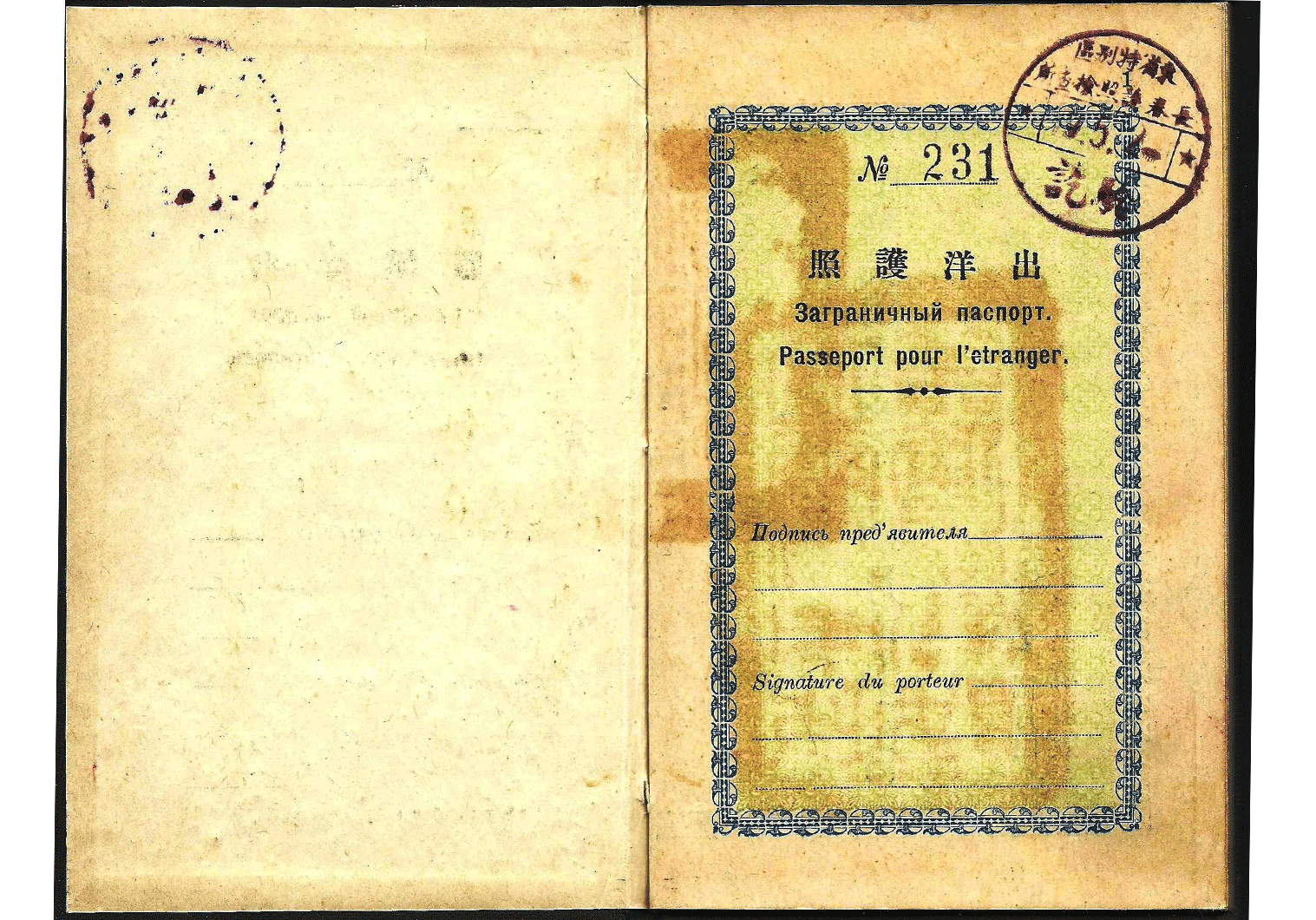

Harbin has a long history of changing hands. At times under Chinese control and at times under Russian control, this could also explain the dual languages that appear on various documents and papers from the 19th century and up to the early 1950’s.

From the late 19th century, followed by the October Revolution and the civil war in Russia that took place from November 1917 to October of 1922, an influx of refugees began to pour into the city. At one point over 40 languages were being spoken there with over 50 different minorities, local and foreign, living in the city and its surroundings. The refugees where mainly White Russians who fled from the former Russian empire and also Jews who began to arrive in the city in the 19th century. The records of this rich community are still kept today under guard.

The needs of these refugees had to be addressed, and the local community and government alone could not undertake this task, and thus foreign aid began to arrive, mainly from Europe and also from the United States, were Jewish organizations sent funds and relief aid to the city.

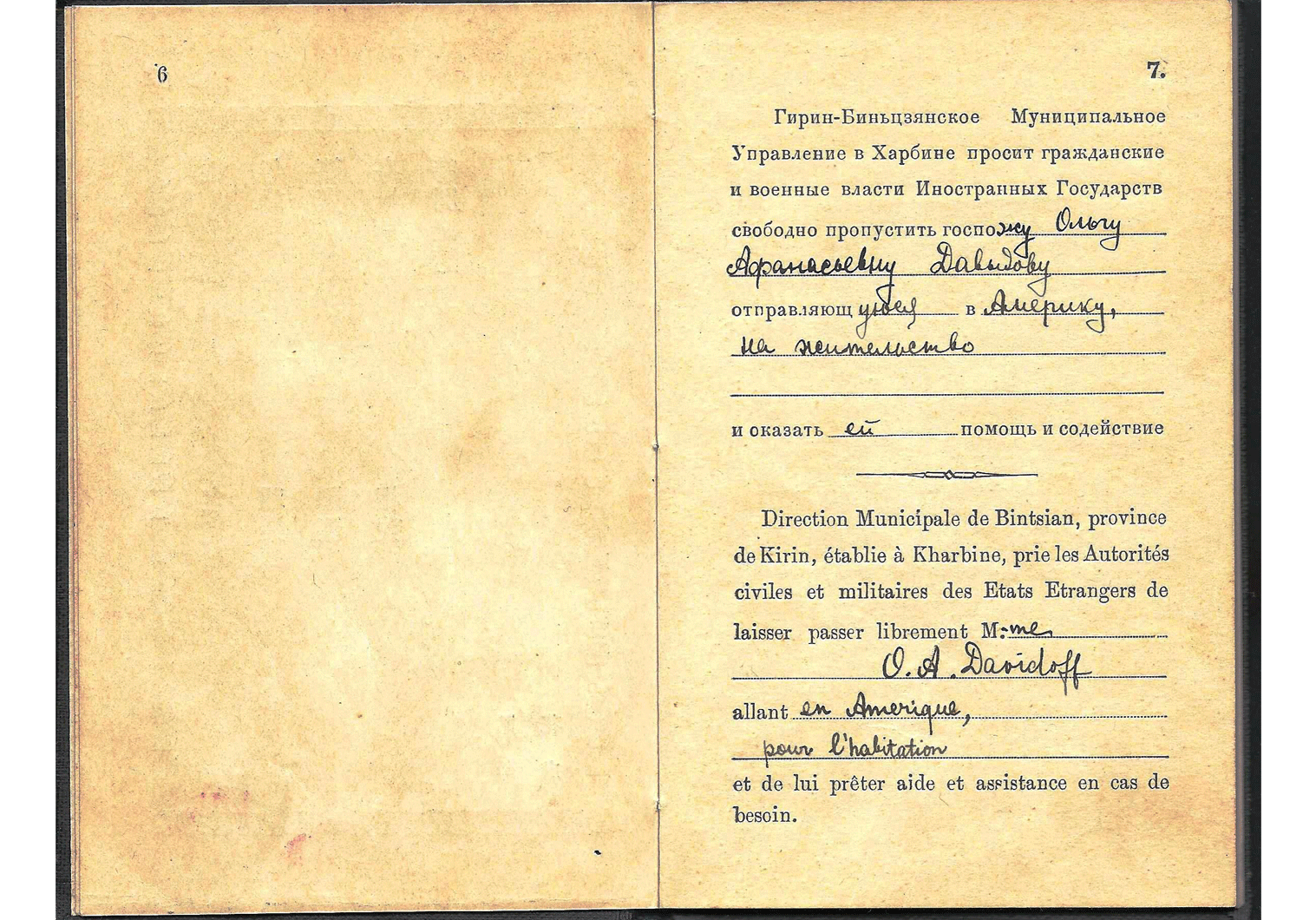

But this could not last forever and eventually some of the refugees began to apply for travel documents and seek for new opportunities abroad, outside of China. The holder of the documents in this article did just that in 1930.

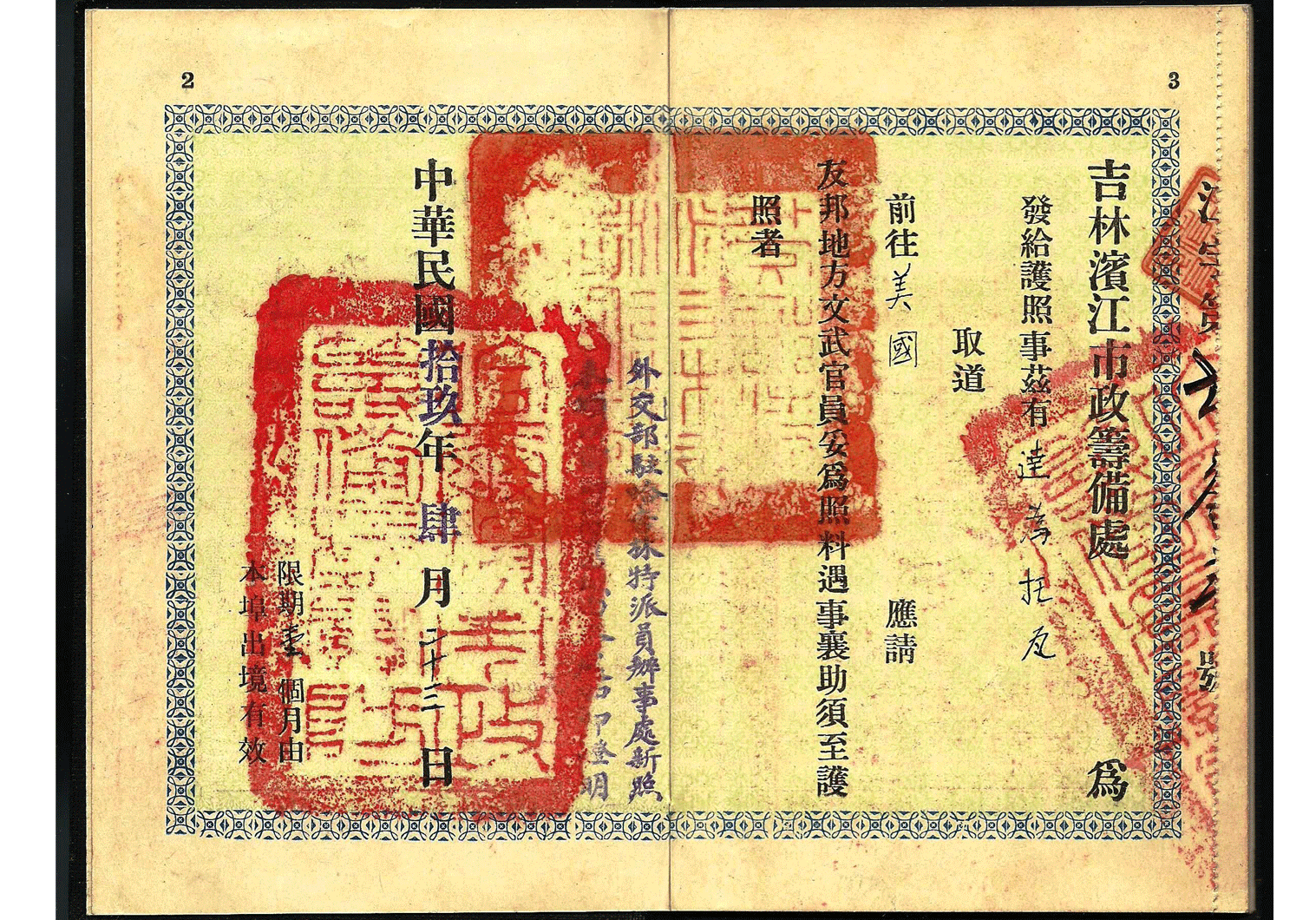

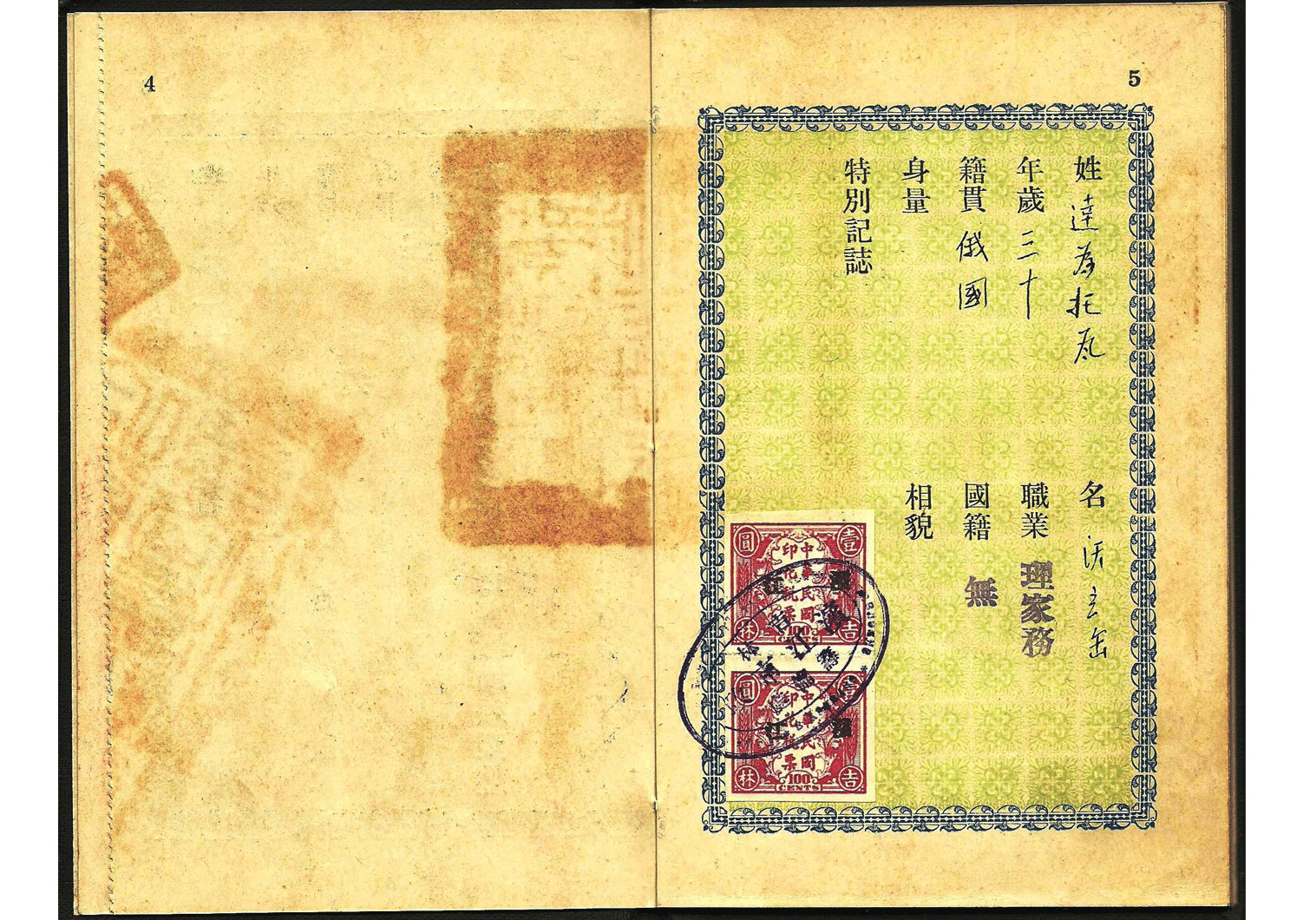

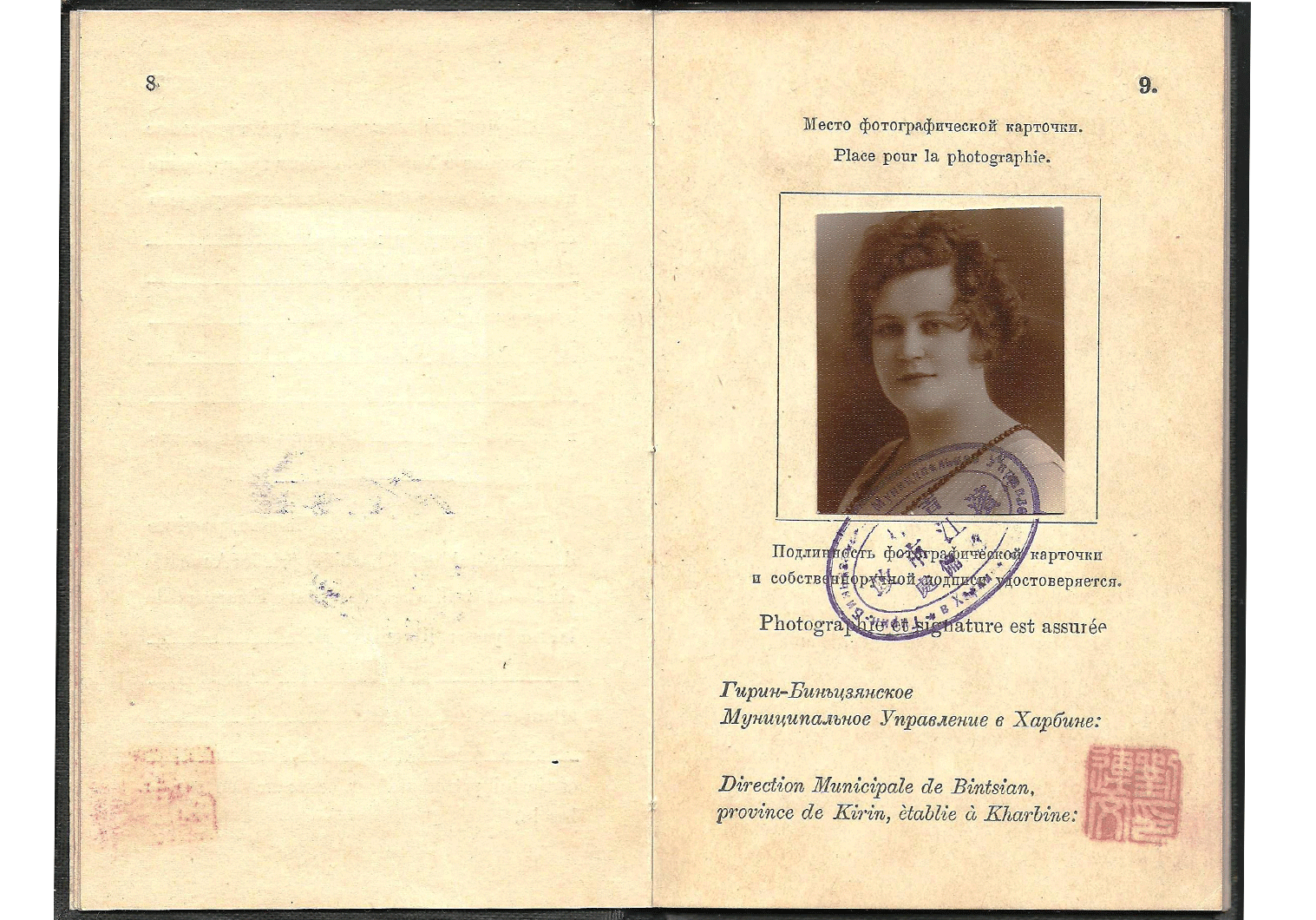

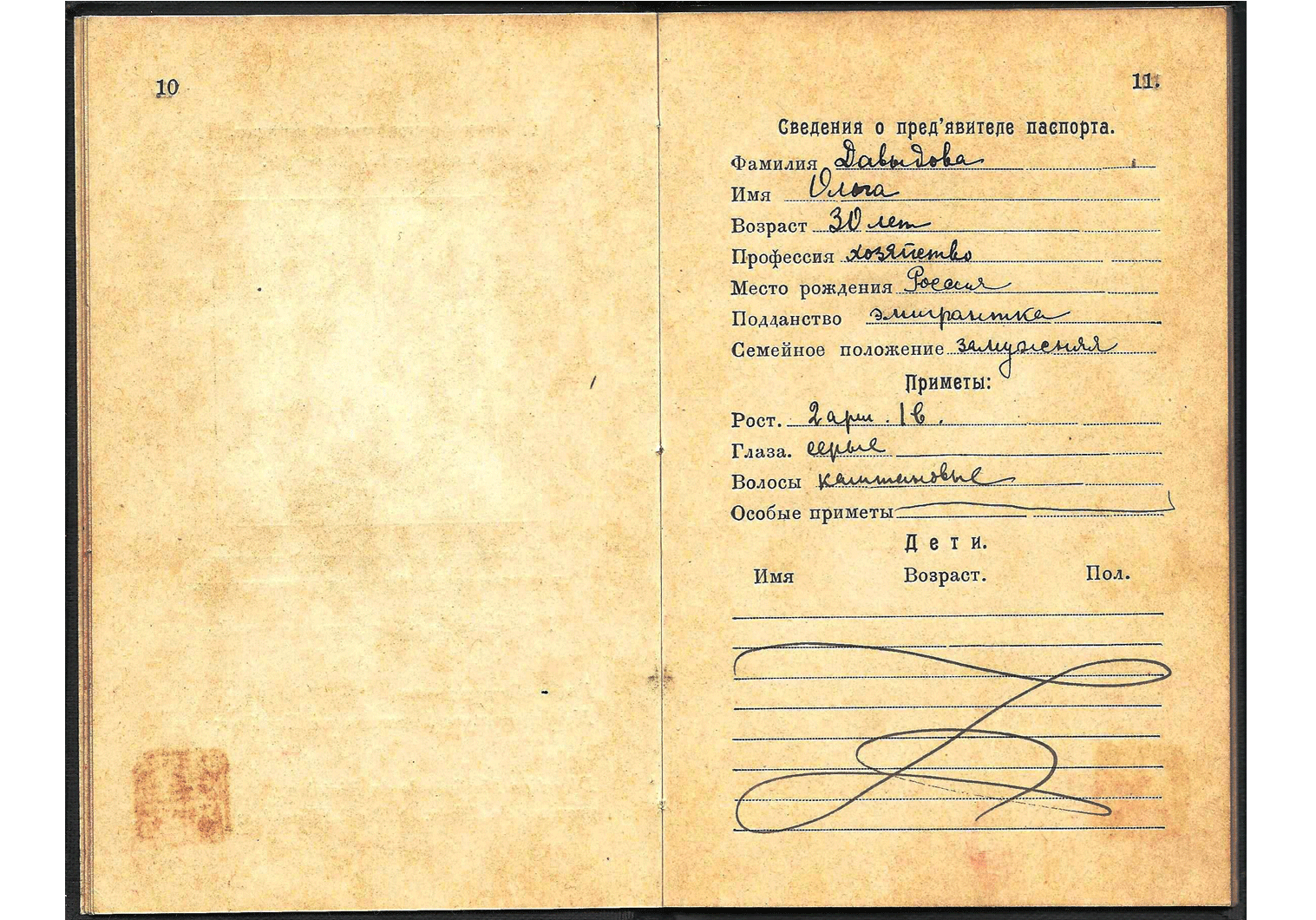

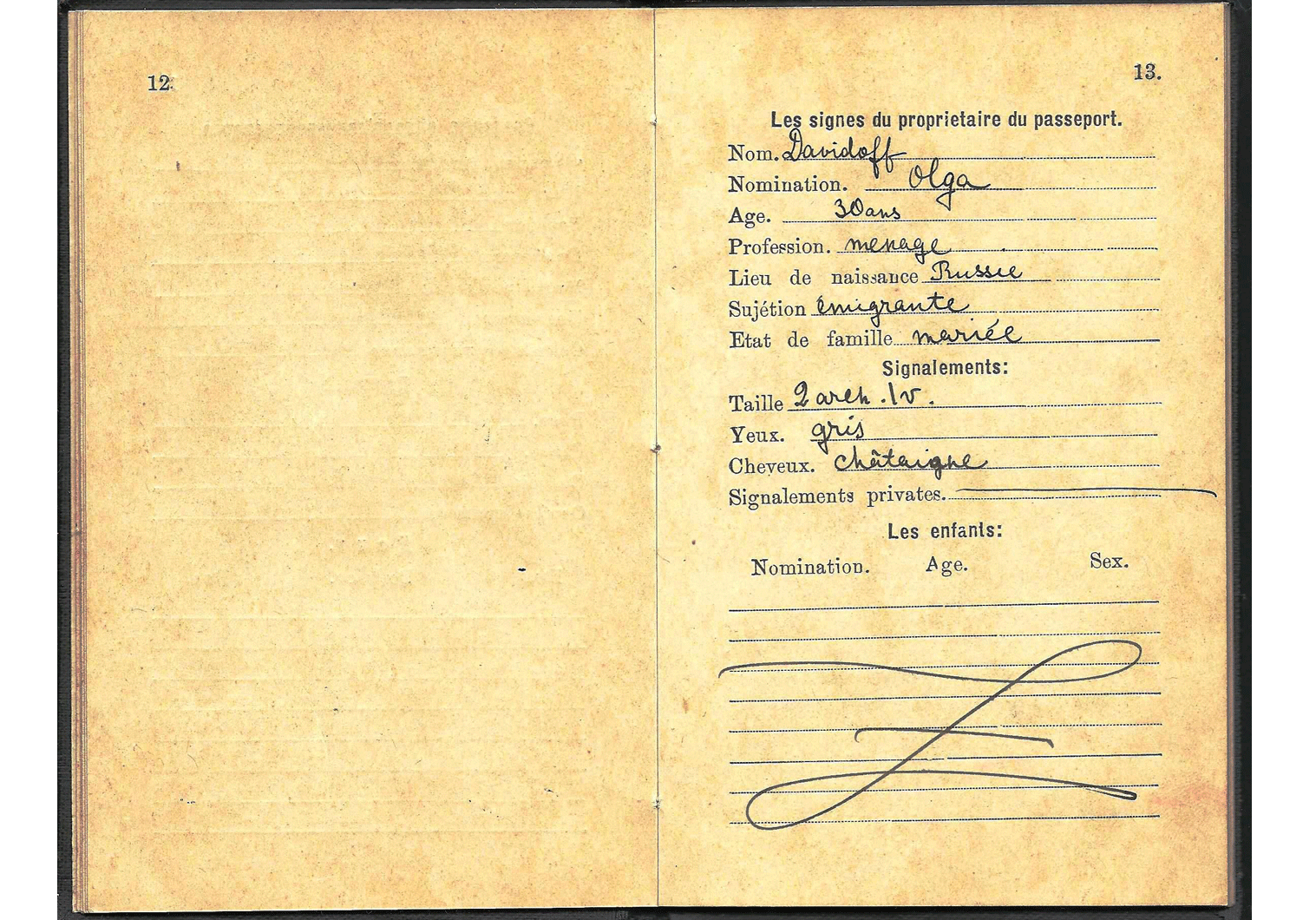

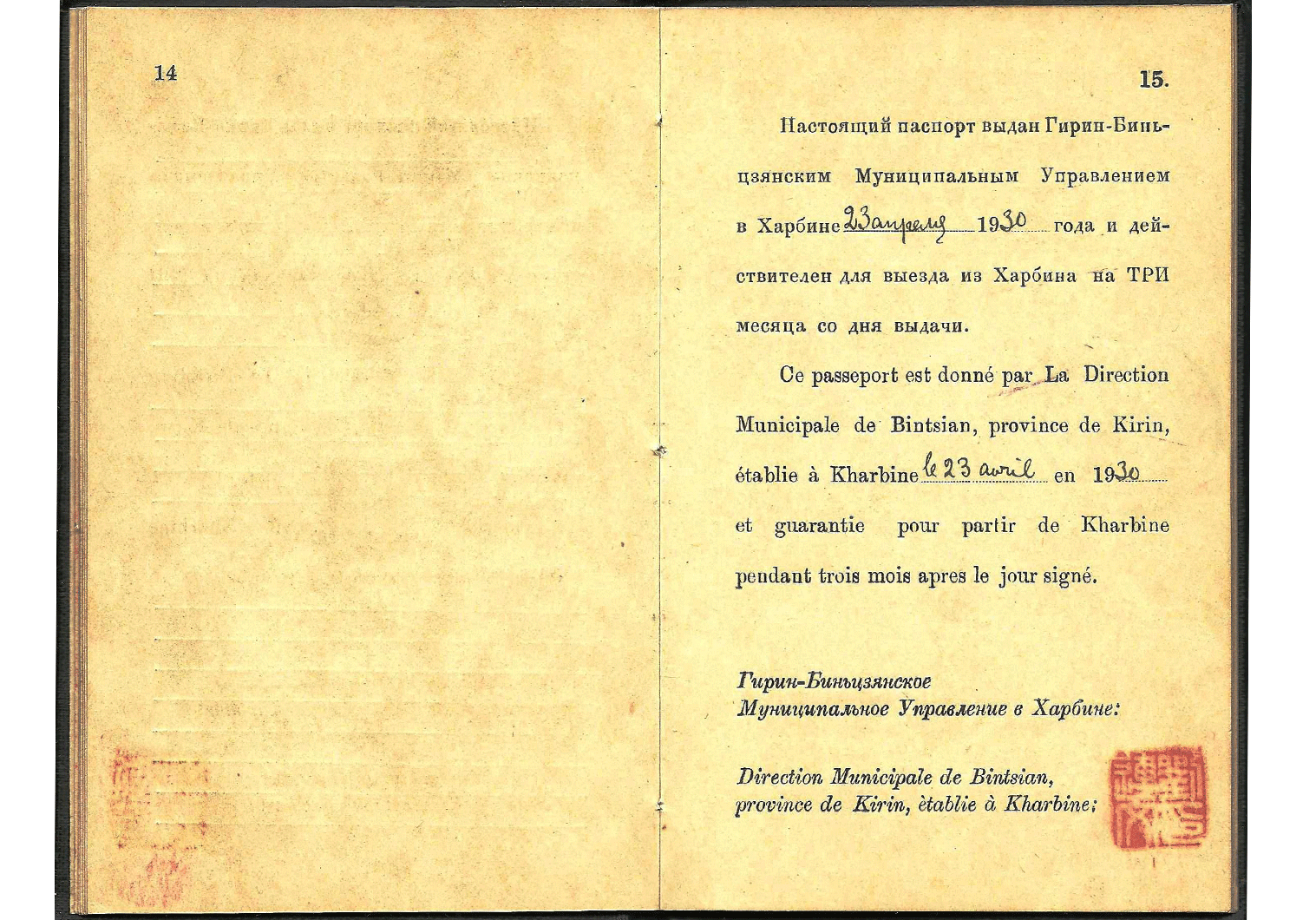

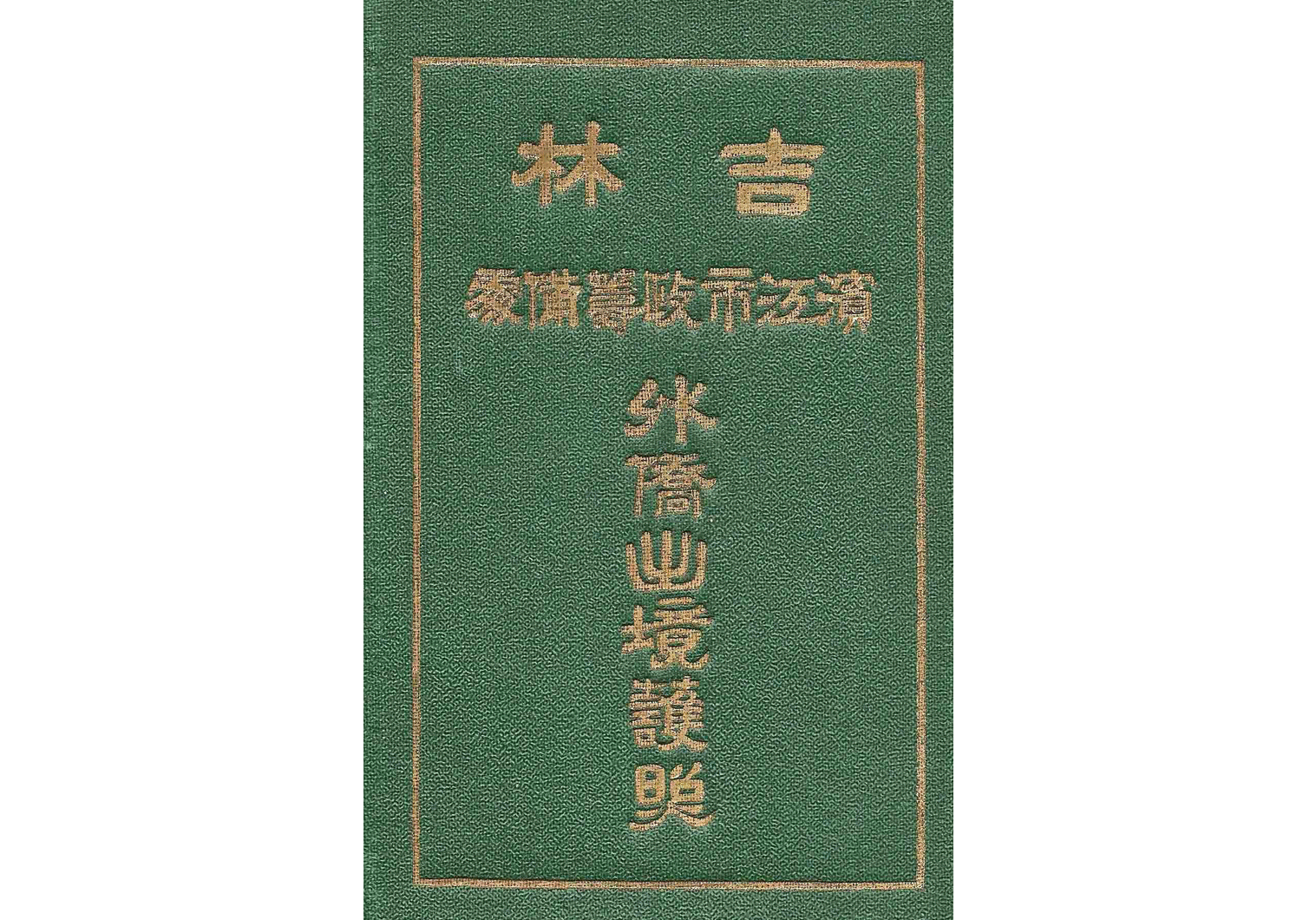

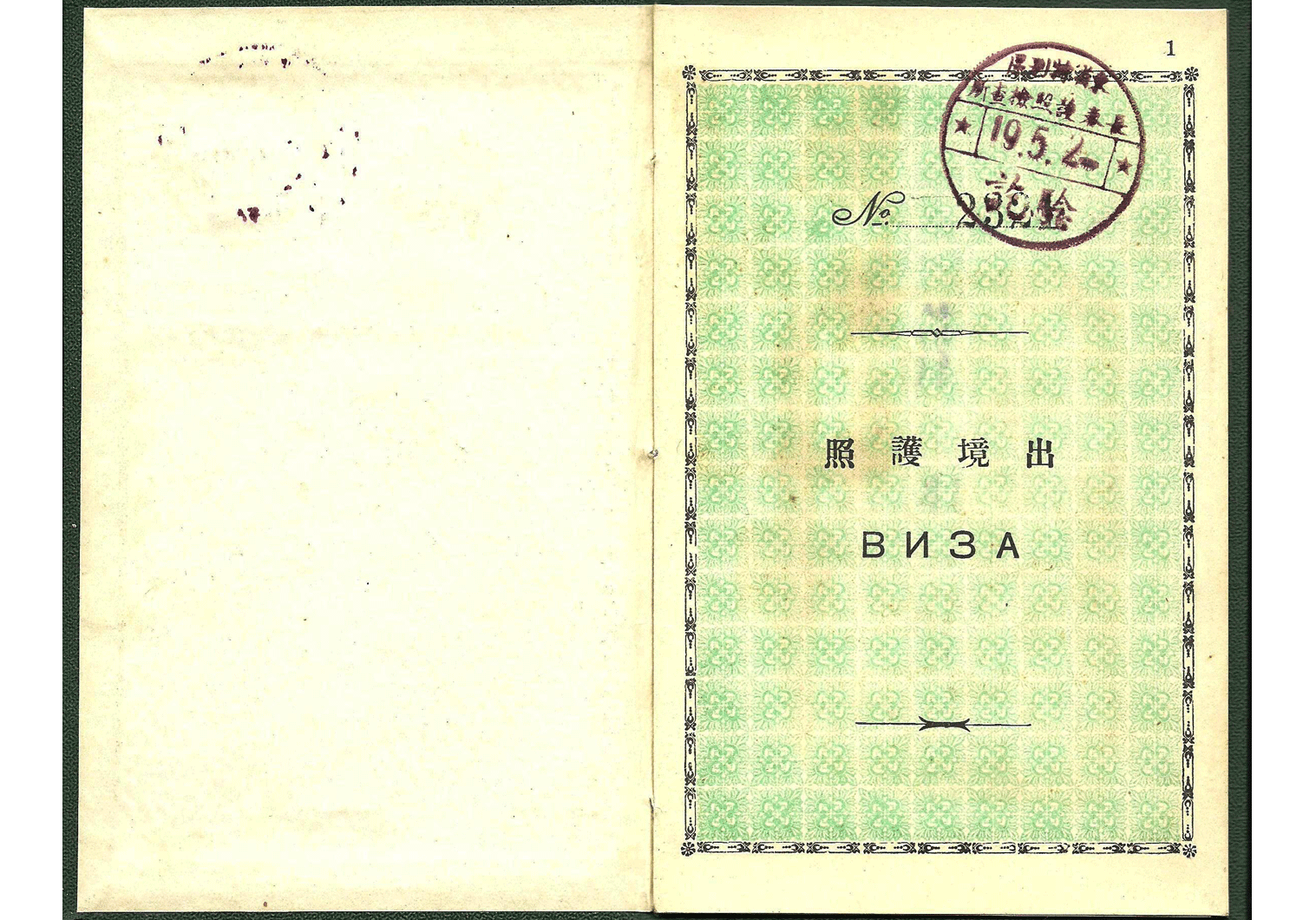

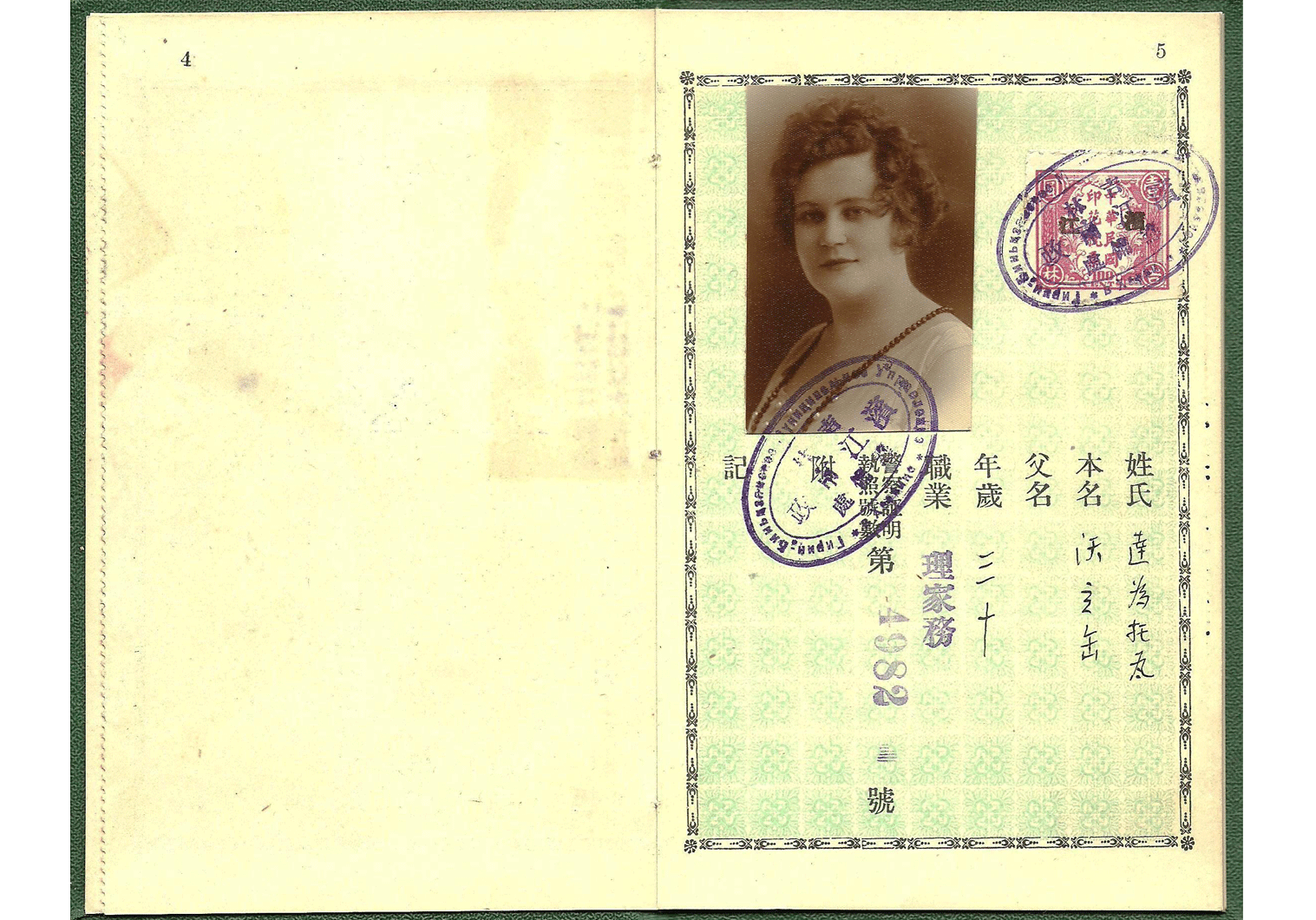

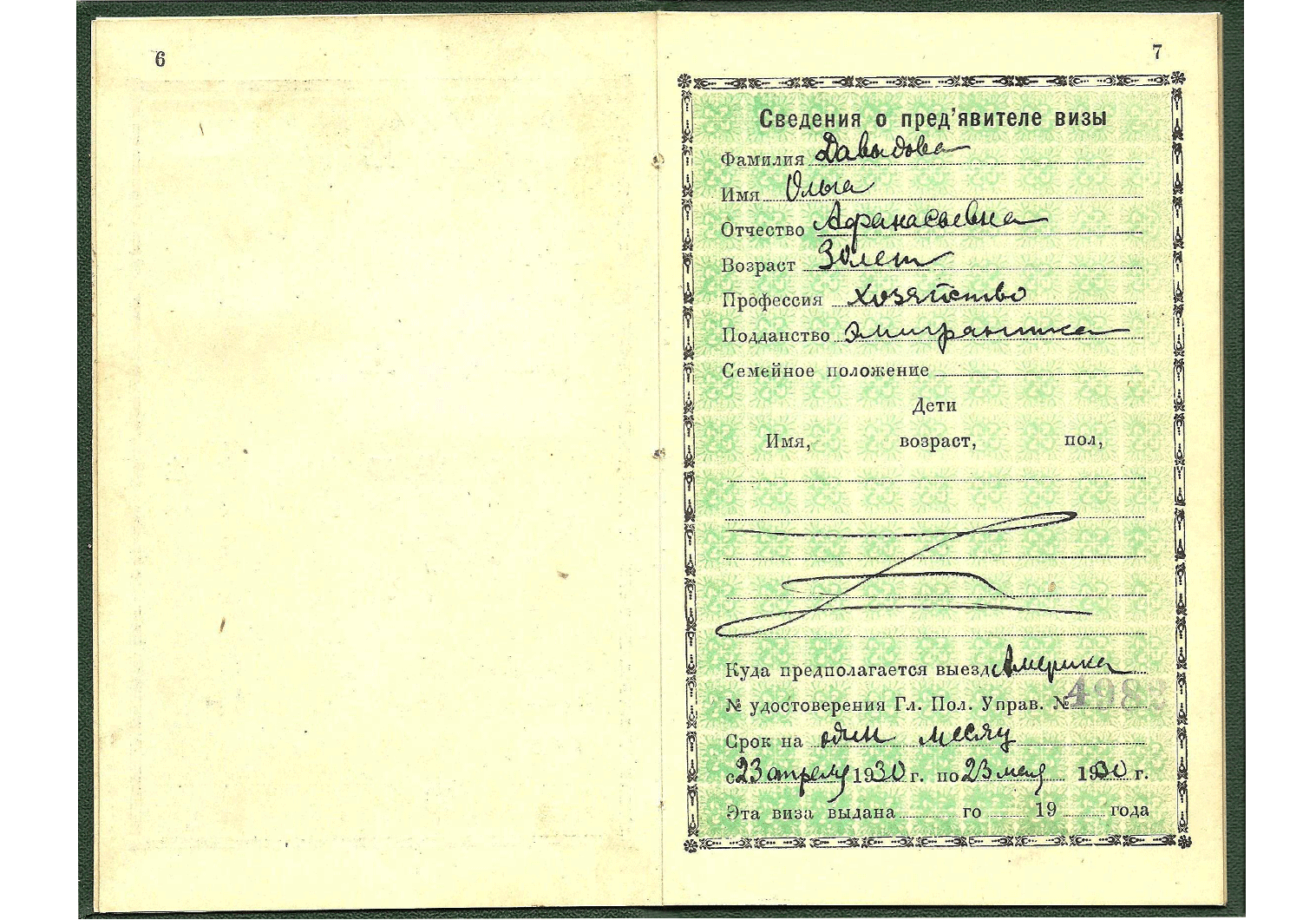

Mrs. Olga Davidoff, aged 30 and being stateless (国籍:无), wife of Vassily Davidoff who was a steam-ship engineer, applied for the Foreigners Travel Document No.231 on April 23rd 1930, at the city of Harbin, Jilin province. It was issued by the newly formed administrative government (operating from around May 1929) “Jilin Riverside Municipal Preparatory Office” (吉林滨江市政筹备处). The issuing body operated for a relatively short period of time from 1929 to 1931, around the time the Japanese invaded the region. Upon examining the document one can find the issuing body’s applied red-chop and rubber-stamp, which reads for “Commissioner of Foreign Affairs Jilin Office, Harbin” (外交部驻哈尔宾吉林特派员办事处). They are both stamped with the big red chop of the “Foreign Department Commission Jilin Branch” (外交部特派吉林分处图章). Another interesting rubber stamp appears as well on the front pages: “New passport to be approved by the department, prior to the temporary passport expiring” (新照末颁以前暂用护照由本处加印证明), and the validity was extremely short for one month.

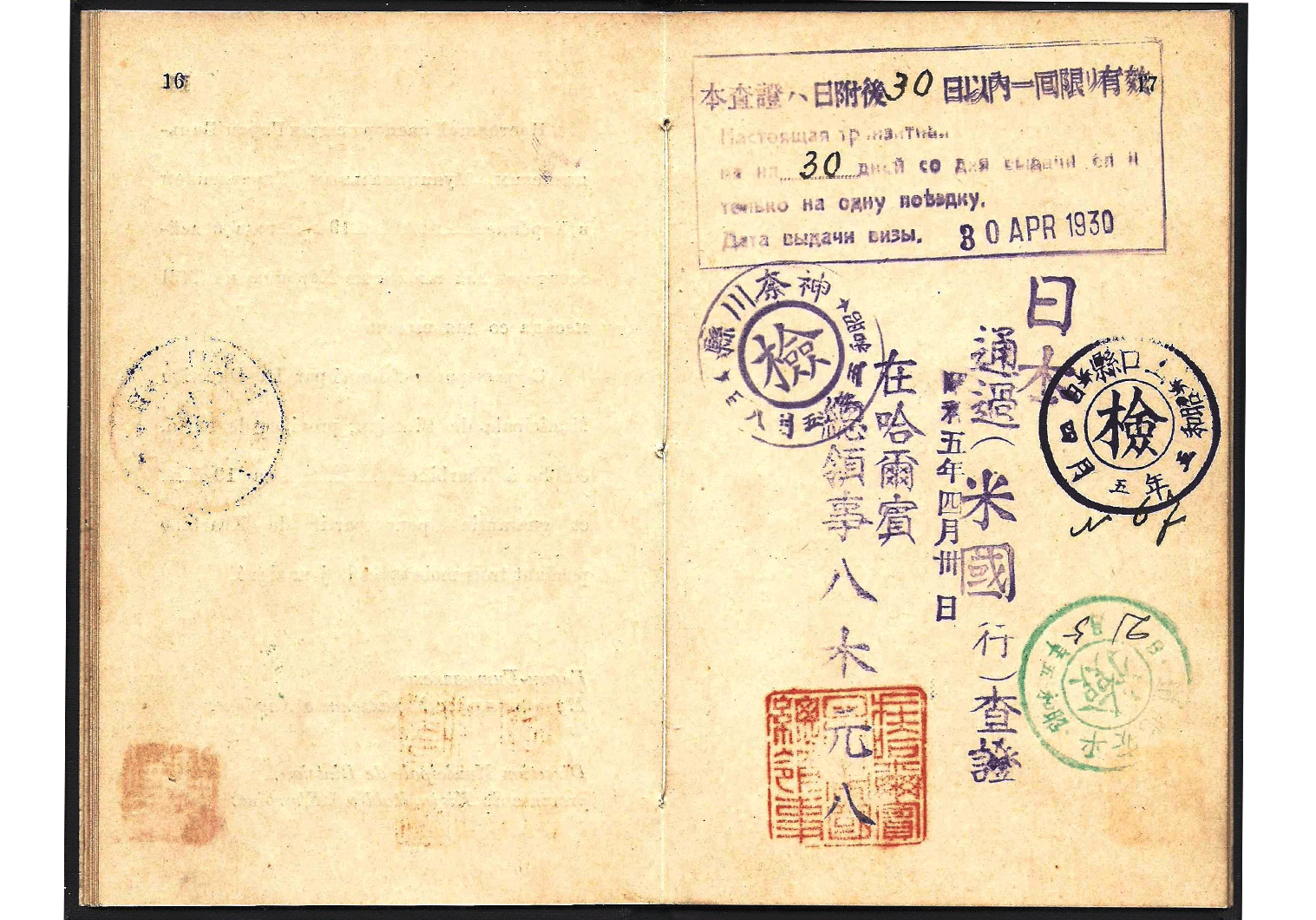

Olga wanted to immigrate to the US, this we can tell from the Japanese transit visa that she obtained, dating April 30th, from the consulate at Harbin. Here are some points about this diplomatic mission: originally located at Guo Ge Li 298 Avenue, Nangang district, served as the consulate from 1921 to around 1929, then moving to 新市义州街27号地 (Xin Shi Yi Zhou 27 street) around 1928-1929. The diplomat who issued the visa was Yagi Motohachi (八木元八), who started his posting in the city on September 27 of 1927.

The travel document has about four applied exit/entry/transit stamps inside, with the first one dating from May 2nd 1930, placed onto the first page, title page, of the document, stamped by the “Eastern Province Special Zone – Changchun Inspection Bureau – Certified stamp” (the city would change its name following the Japanese occupation to Xinjing 新京 – the capital of Manchuria).

Second stamp is from North-Western North Korea (平安北道), applied on the journey to Japan.

Third stamp dates from May 8th, applied on entering Japan at Yamaguchi Prefecture (Honshū Island).

Fourth and final stamp is the transiting point at Kanagawa Prefecture (神奈州县).

One point that needs to added here, is that these travel documents would normally come together with another certificate, which though it looks like a passport, it is not: Police clearance to leave the borders, when one has no criminal background or legal issues opened against him or her. The document’s serial number is surprisingly low as well and follows the traveler’s first document number with being No. 232

Once the Japanese established Manchuria, they would issue very similar type of passports/travel documents, with the issuing body and title being the only changes inside.

These travel documents assisted many in starting a new life abroad. Others would follow before and during the occupation to leave North Eastern China, with this stopping once World War Two broke out: the Japanese would start transporting enemy nationals to various internment camps they would operate in China, for example, around Mukden, Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai and also Hong Kong.

Thank you for reading “Our Passports”.

Andre's Vaart

Nicely done, Neil. It’s pretty interesting how diverse the populations of Chinese cities of the time. I would read of foreign restaurants working up to the PRCs creation.

Thank you for this

Neil

Most welcome Andre, thank you for the comment.