The Spiegel family saga

Internment at Mauritius Island during the war.

This is the story of a Jewish family that was caught in Austria of 1938, following Hitler’s march into Vienna, in what was termed as the Anchluss.

The tolerant reaction of the local population to the violence perpetrated by the Nazis upon the Jewish citizens convinced many that it was the time to leave their beloved Austria. Scores flocked various Jewish organizations and foreign embassies in the hope of securing exit visas that would permit them to escape the unfolding events and those that would follow. One of those was the Palästina Amt Wien (Palestine Office Vienna).

1,000 Jews from Vienna managed to obtain their passports and exit visas thanks to the help of the Palestine Office Vienna that was located at Marc Aurel Strasse. Their offices were opposite the Central Agency for Jewish Emigration in Vienna (Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung in Wien), headed by Adolf Eichmann when it opened on August 20th of 1938: it consisted of its head, deputy and about 20 staff members, all of whom were SS members:

- Anton Brunner

- Ernst Brückler

- Anton Burger

- Ferdinand Daurach

- Herbert Gerbing

- Ernst Girzick

- Richard Hartenberger

- Franz Novak

- Karl Rahm

- Alfred Slawik

- Franz Stuschka

- Josef Weiszl

- Anton Zita

The office was in charge of hastening the forced immigration of the Austrian Jewish population and their deportation, also by forced measures after October of 1939, following the outbreak of war. One of the main objectives was also to rob the poor victim’s belongings and ensuring that heavy taxes were also implemented as well. All had to pay for their own forced immigration expenses and “immigration payment” too, meaning all travel costs involved (by October of 1938 they were already approving close to 350 immigration requests per day).

One of the Jewish representatives who worked at the Palestine Office Vienna was a young native called Georg Überall (later he would change his name to Ehud Avriel ) who was active up to 1940 with the attempts to assist the immigration of his county’s Jews to British Palestine. After the annexation of Austria it became more and more difficult to obtain immigration visas, where more and more countries refused to allow Jews into their borders. The hardening of the British position on this matter and restricting the immigration quotas to an unbearable amount contributed at the end to the death of many European Jews: Had they opened the gates without objection, countless of Jews from all ages would have managed to survive the war and the annihilation they faced at the death camps.

One example of the tiring efforts this office took, but sadly, without the positive outcome that was wished for, was the immigration of about 1,000 Viennese Jews (via a collective passport) at the end of 1939 that managed to travel all the way to Bratislava, a transit point for fleeing refugees. From there, after substantial amount of cash changed hands with the local police chief, they were permitted to sail down the Danube to the Yugoslavian port of Kaldovo. Due to the cold winter that followed, they remained on Yugoslavian territory throughout the winter. Finally, they were moved to smaller port of Sabac on September 18th 1940, near Belgrade. But they did not leave on time: After the German invasion of Yugoslavia in early 1941, they were caught by the invaders and murdered around April 7th.

As mentioned earlier, Bratislava, or Pressburg in German, was a main transit point for transferring Jewish immigrants & refugees out of Europe during 1939-1940. The newly formed Slovakian state was in desperate need of funds and it aided, in some strange ways, to the plight of these people by temporary transit through its borders (Ehud Avriel was able to secure an open telephone line via the Slovakian consul at Vienna, for a modest sum of 10 pounds per call, that enabled him to place undetected calls to his operatives abroad (he was working with the Jewish rescue efforts in the Mandate)).

The recue efforts included the hiring of boats that would take the immigrants via the Danube and also the Black Sea to its final destination. Some were obtained via the Donaudampfschiffahrtsgesellschaft (Danube Steamship Company), which took them all the way to Constantia or other sea ports such as Tulcia.

The article here will bring into light the saga of a Jewish family that ended up under Nazi rule in their beloved city of Vienna.

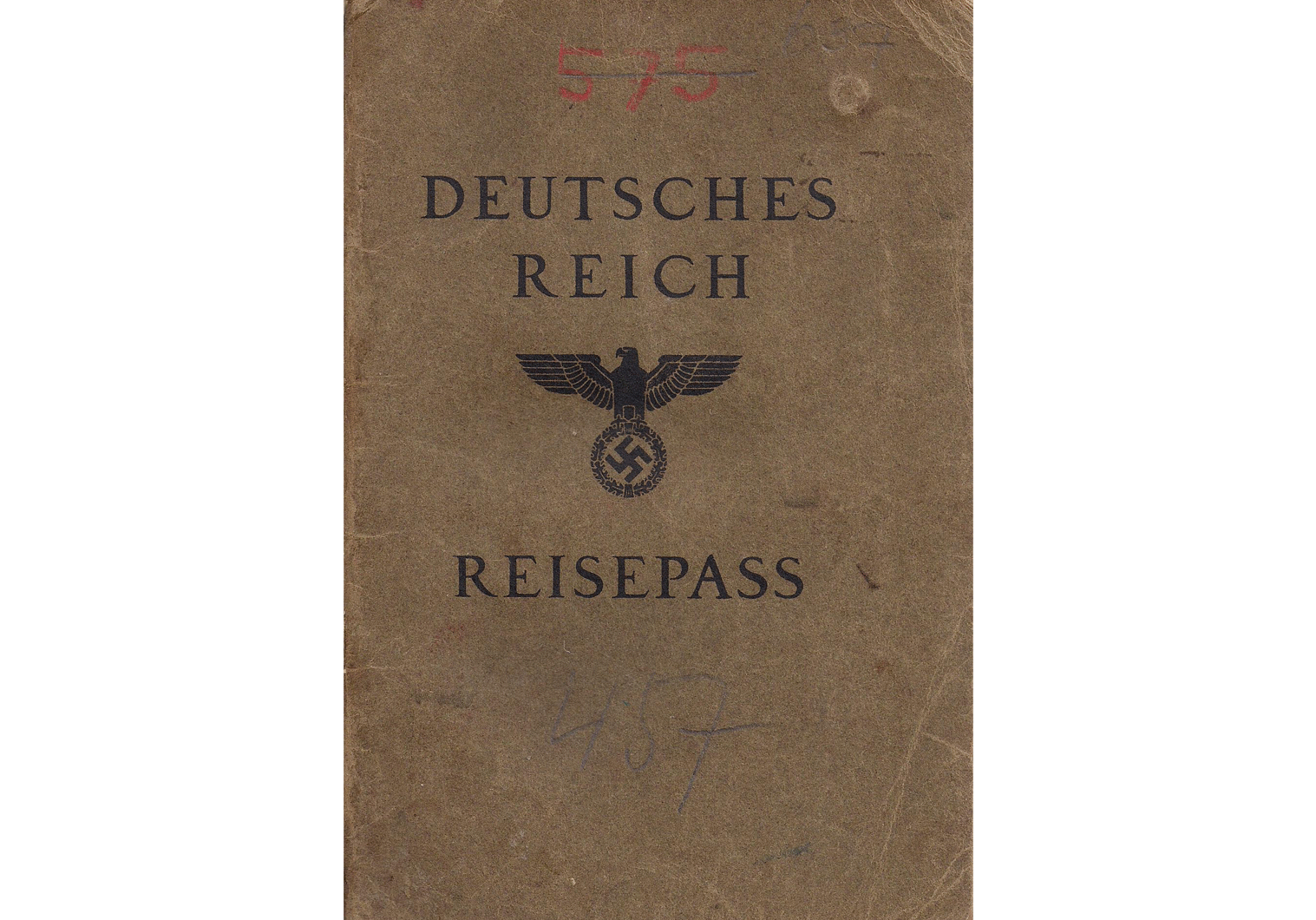

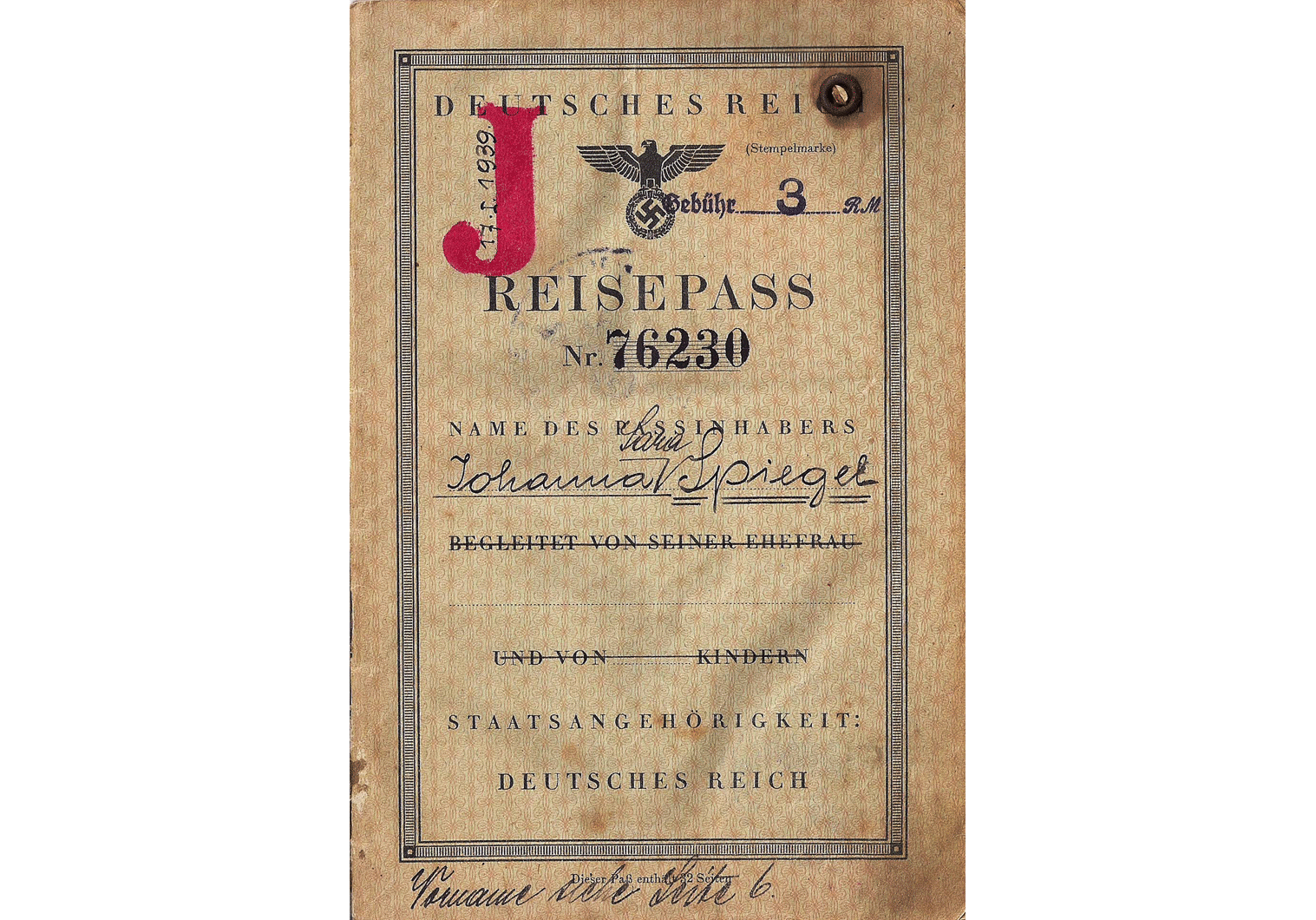

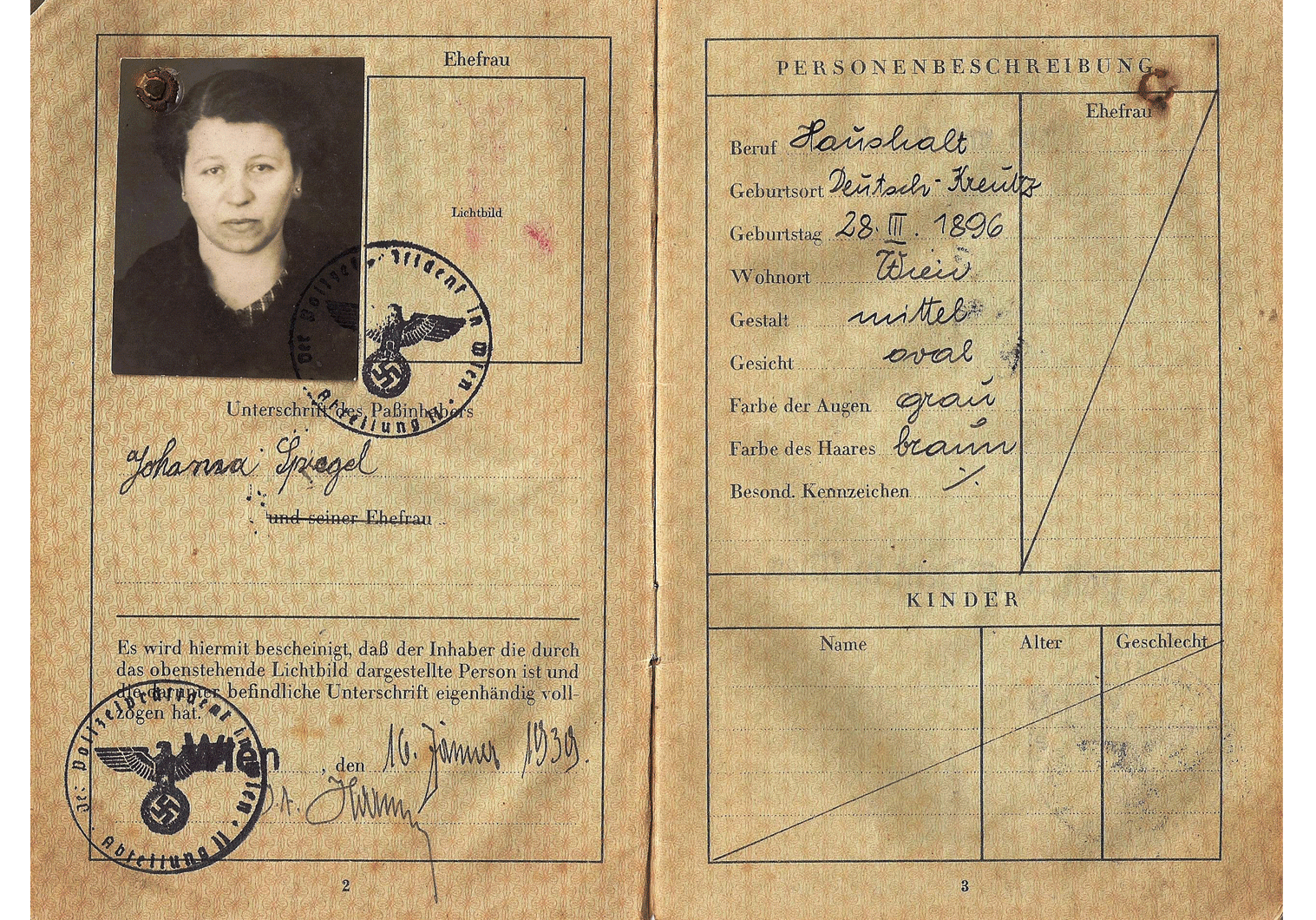

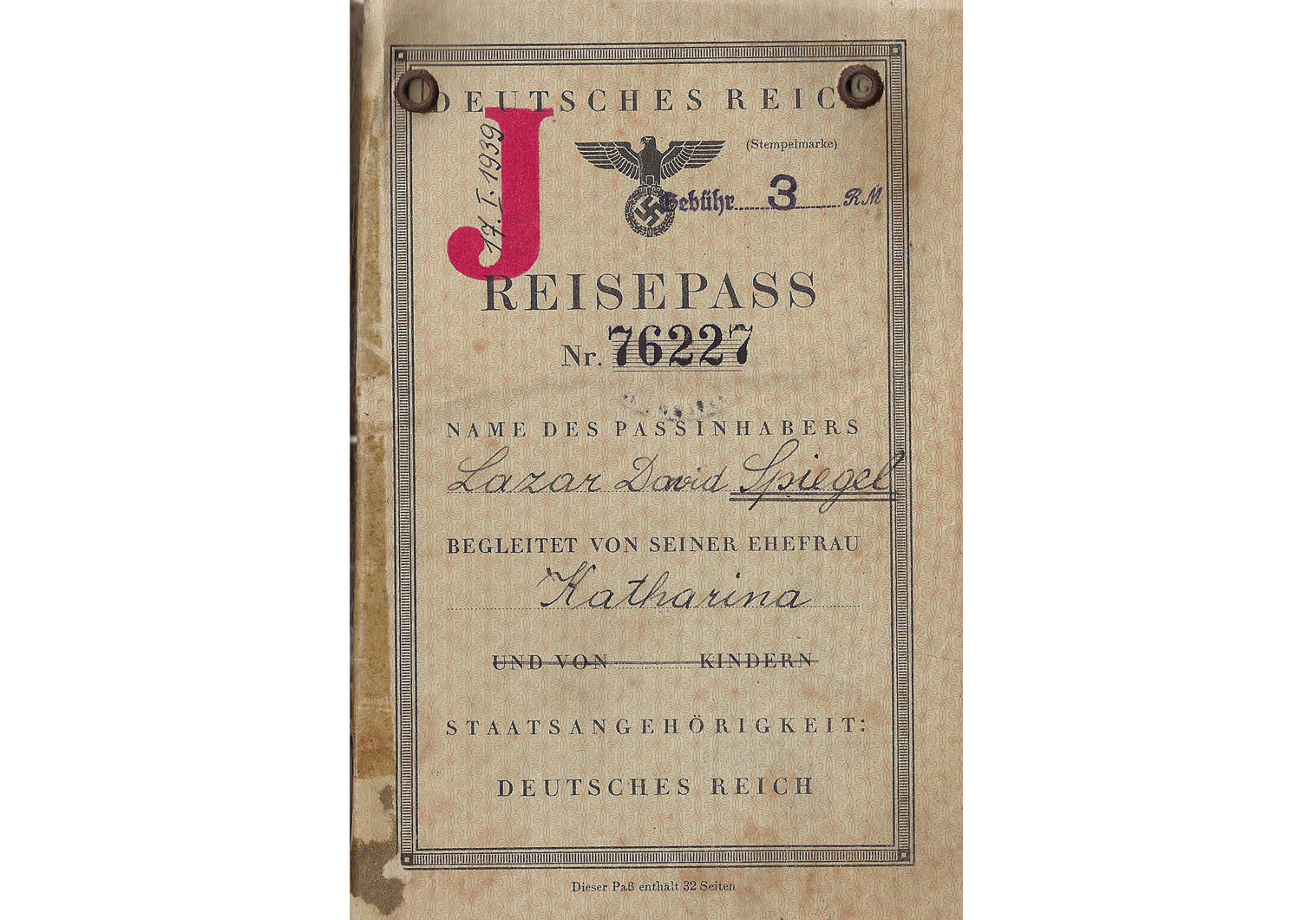

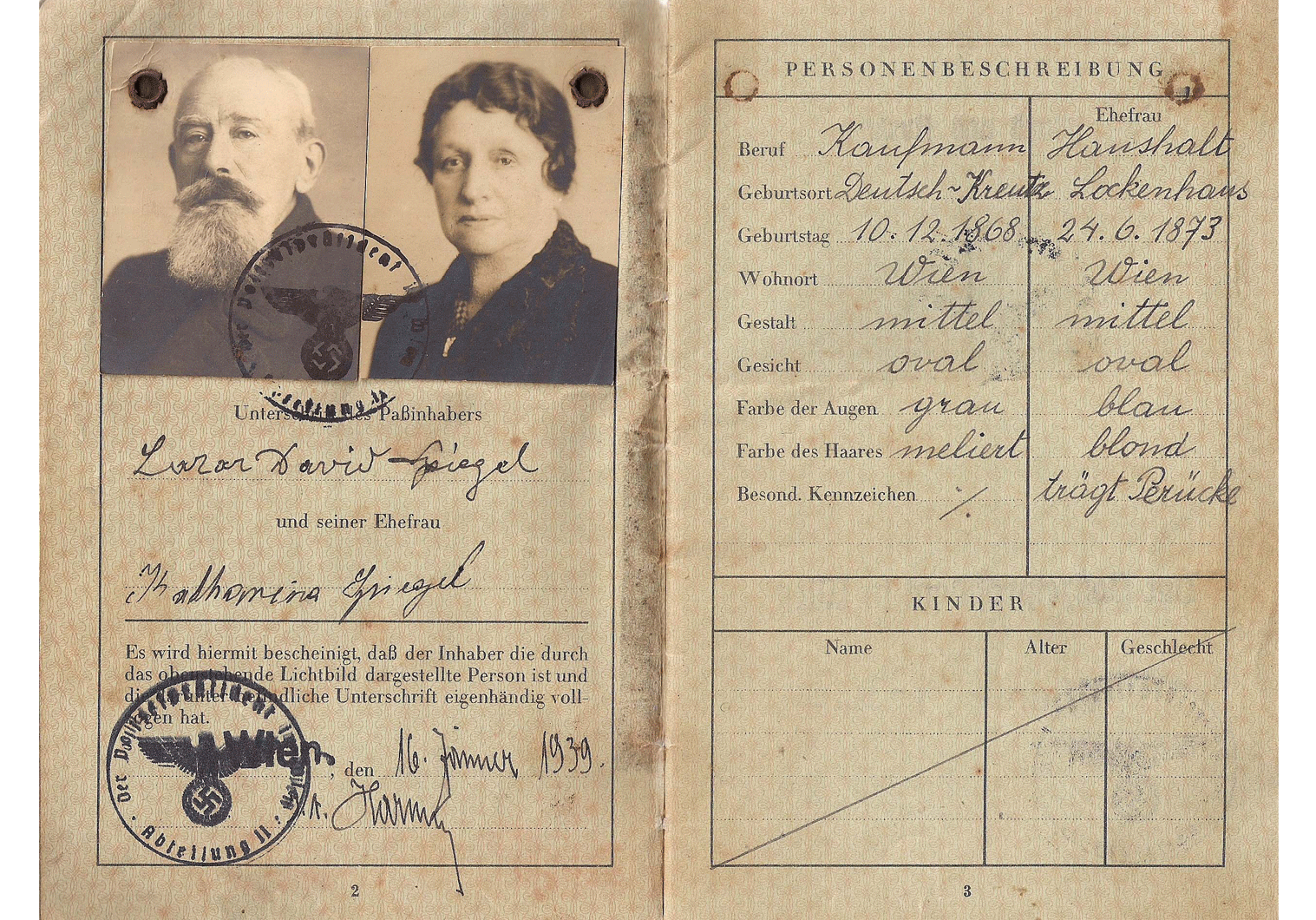

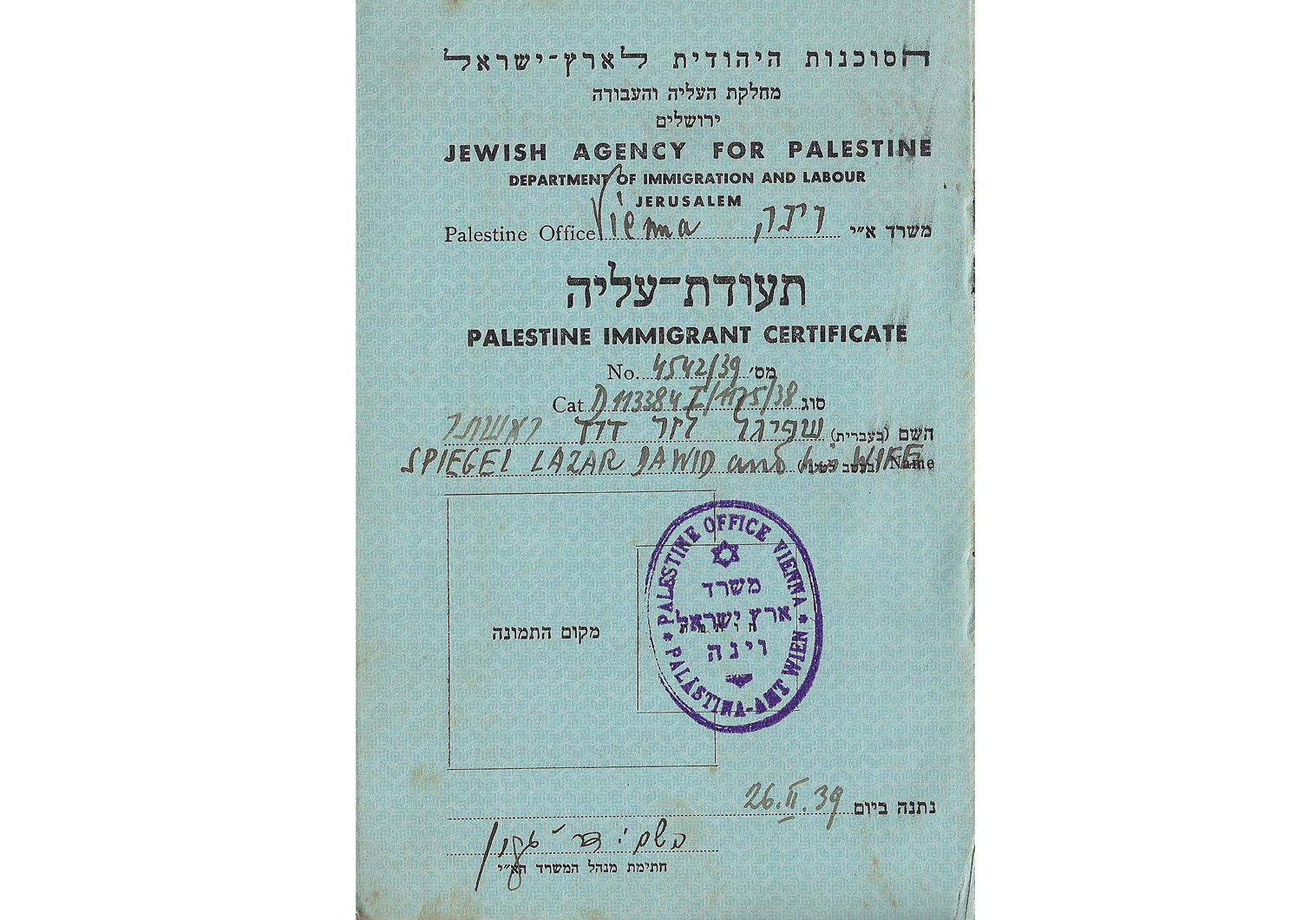

Passport numbers 76227, 76229 & 76230 were issued to husband and wife Lazar David and Katharina Spiegel and to their two daughters Johanna (Chana) & Berta. All passports were issued on January 17th 1939 by the Polizeiprasident in Wien, but as mentioned at the beginning of the article, this was a cover for the real issuing authorities: Eichmann and other SS officials working at the Central Agency for Jewish Emigration in Vienna.

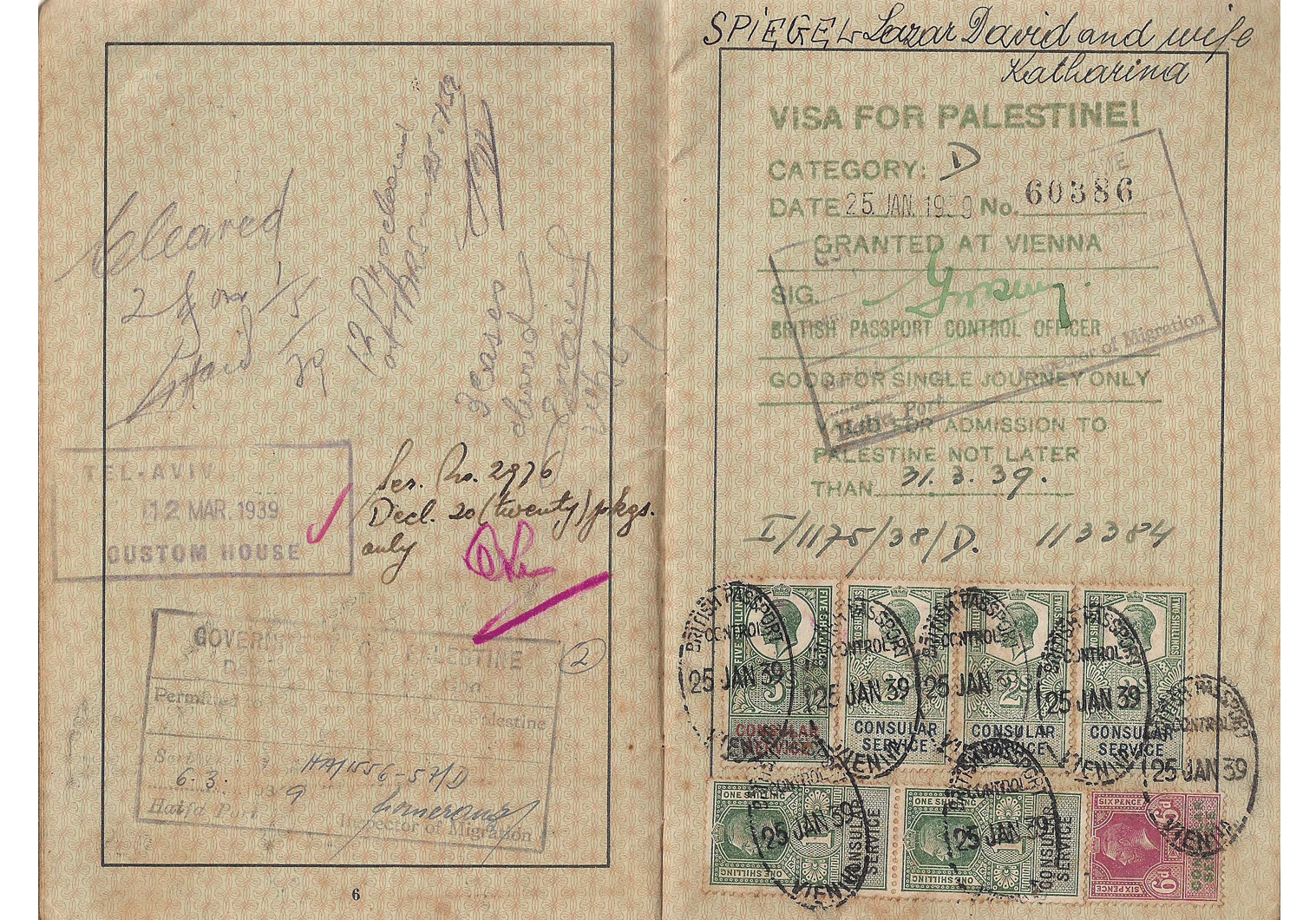

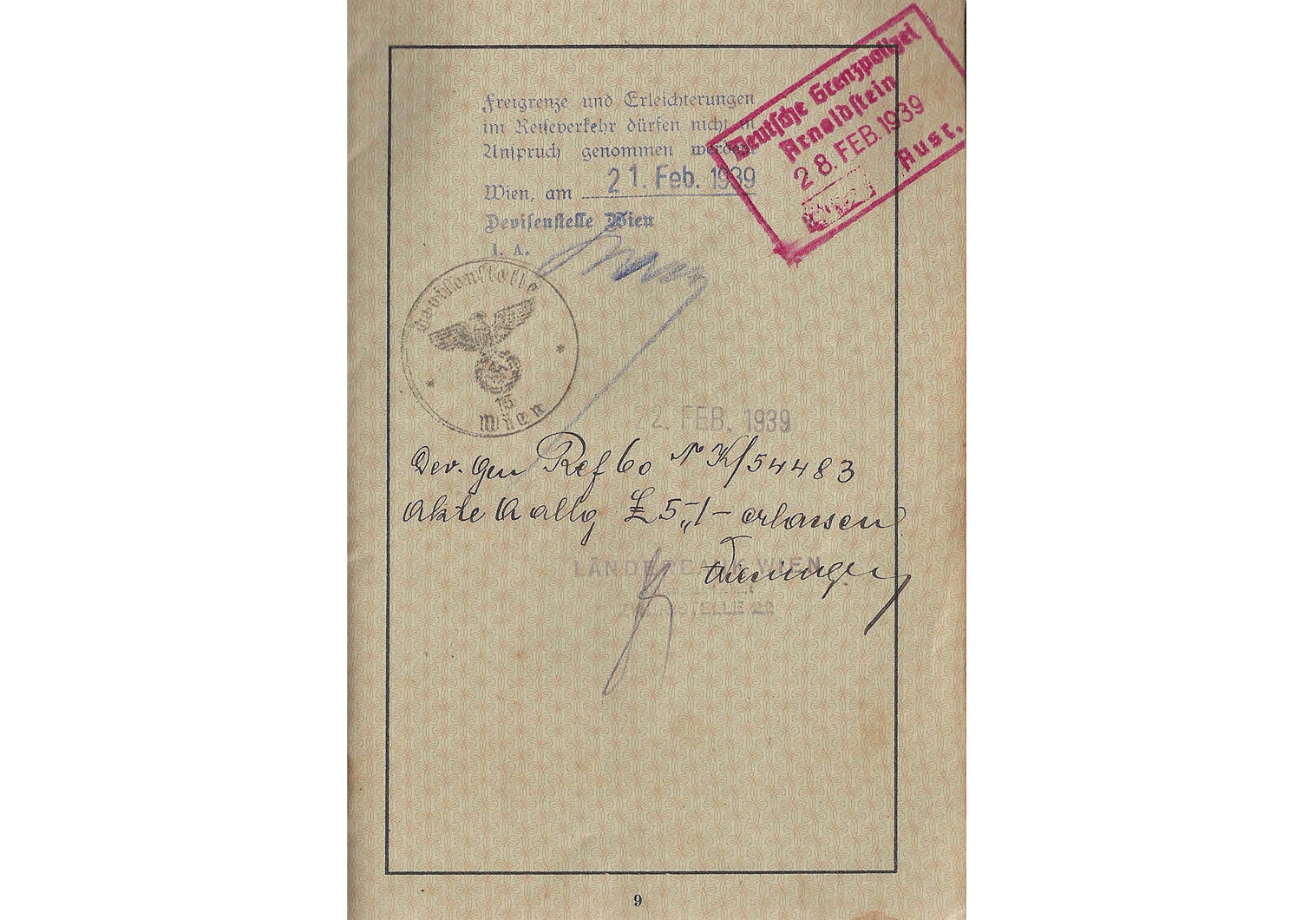

The father Lazar was a prominent and very wealthy Jewish community member that was apparently able, for himself and his wife only, to obtain the desired and rare British immigration visa for Palestine. Visa number 60386, category D (I/1175/38/D. 113384), was granted at Vienna on January 25th 1939 by G.W.Berry at the passport control office. Admission into the Mandate was limited to the 31st of March (only after this could they receive the Jewish immigrant’s certificate from the Palestine Office Vienna). Apparently, maybe due to their connections and wealth they did not require the German exit visa; though some annotations on page 9 indicated that tourist traveler would not be possible to enjoy border facilities. They took the odd route of train via the German-Italian border crossing of Arnoldstein on February 28th. The two boarded a boat at the port city of Trieste 3 days later, entering Haifa port on March 6th.

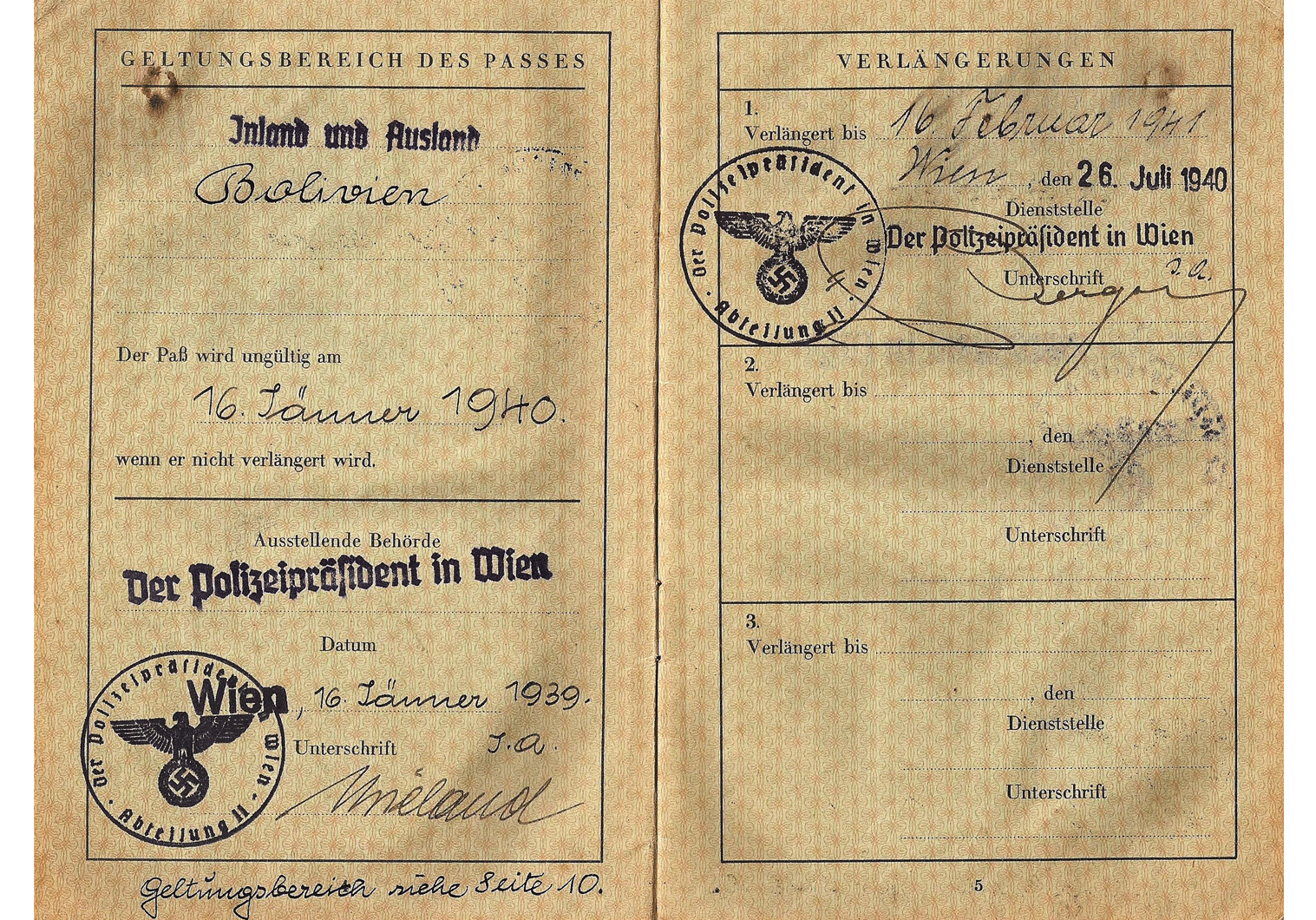

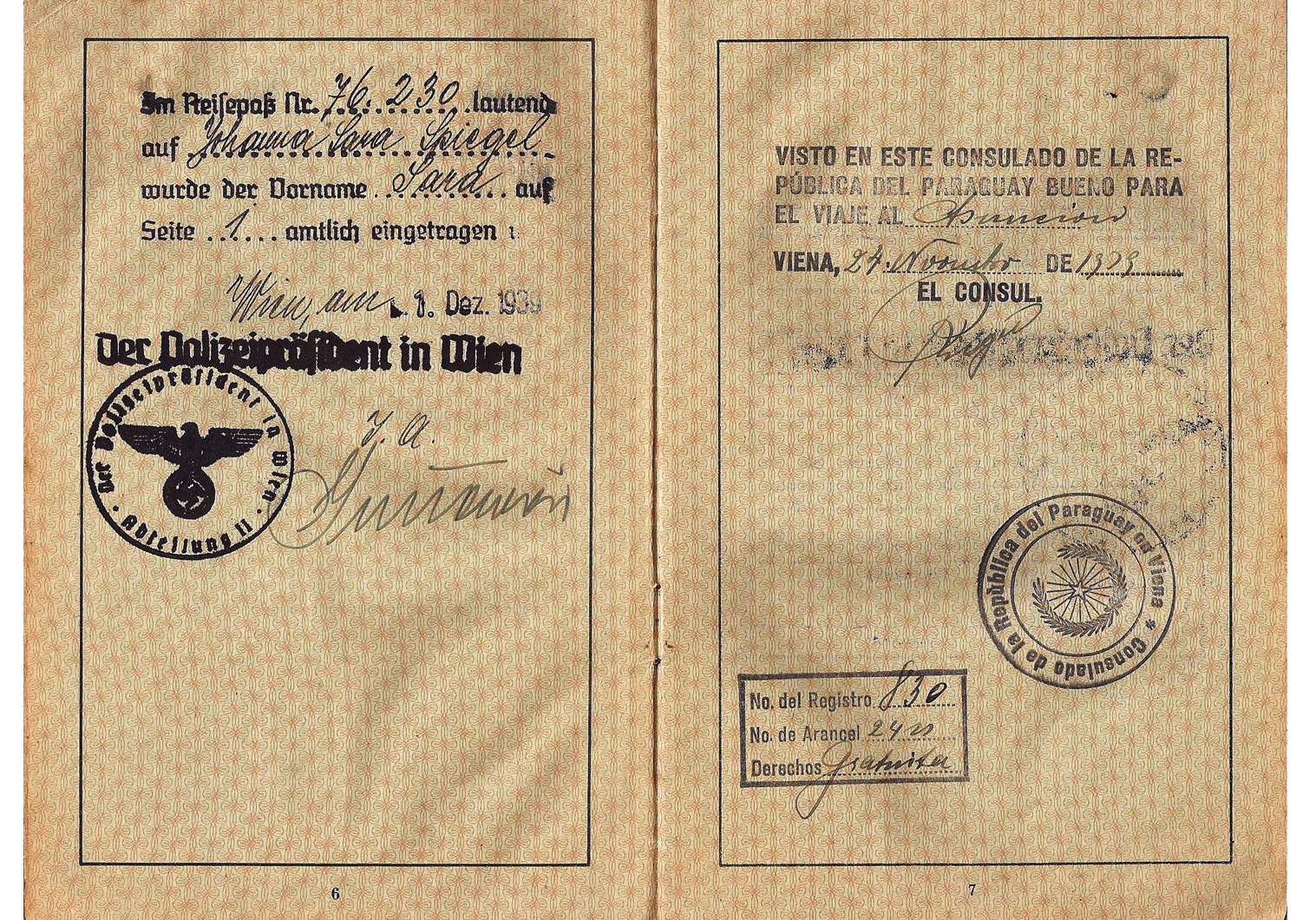

Johanna and Berta did obtain at the end of the year a Bolivian visa from the consulate at Vienna on November 24th but did not make use of it. Their German exit visa obtained a week later was also not used to leave Austria and was later cancelled by the same “issuing office”. By this time they had their names amended with the addition of SARA added to the title page (an anti-Semitic racial mandatory requirement imposed on ALL Jewish males & females from 1939):

An official “explanation” of this can be found inside both of their passports on page 6. For reasons not known, they did not leave to Bolivia, possibly attempting to find their way to British Palestine where their parents had arrived safely earlier that year.

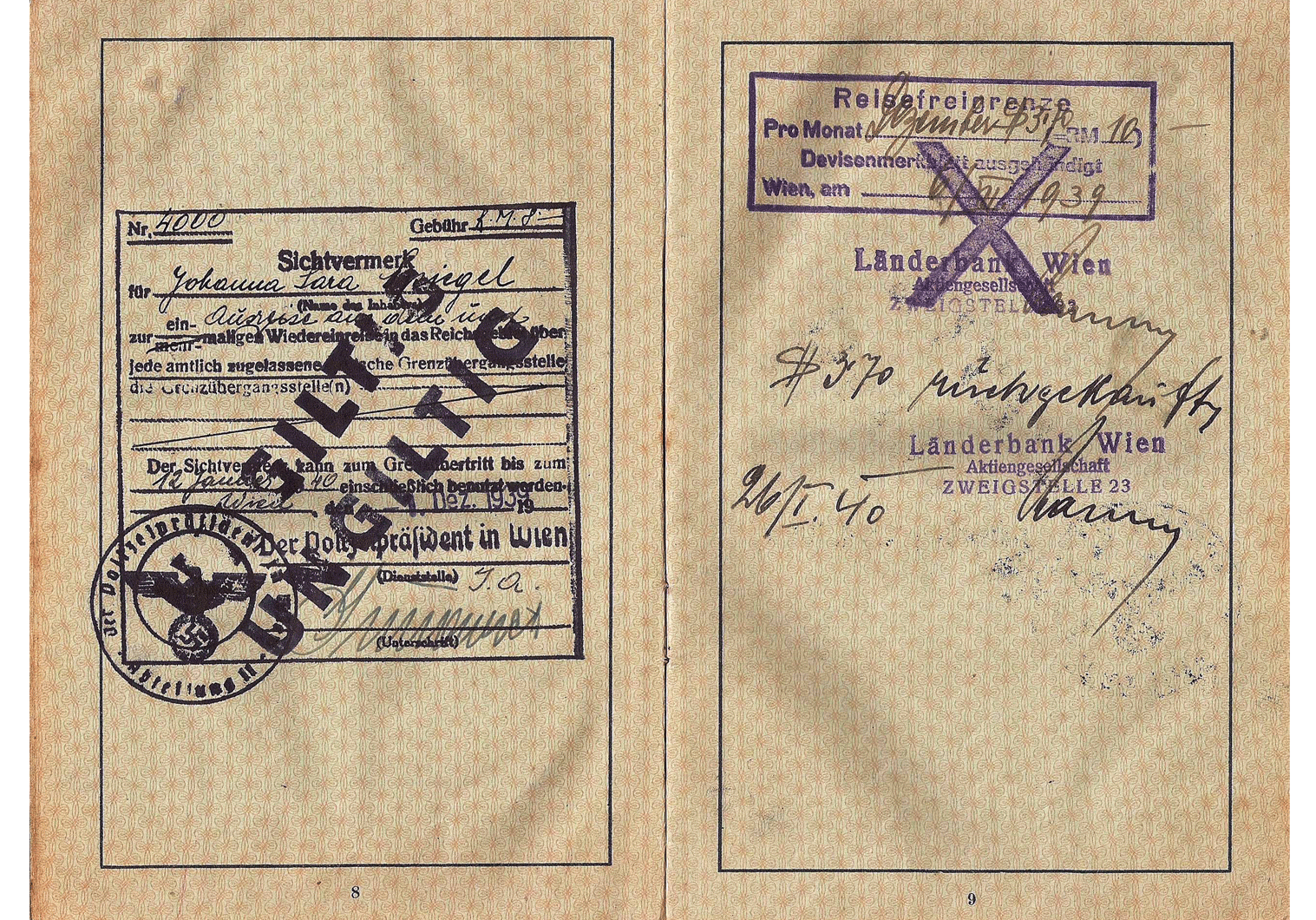

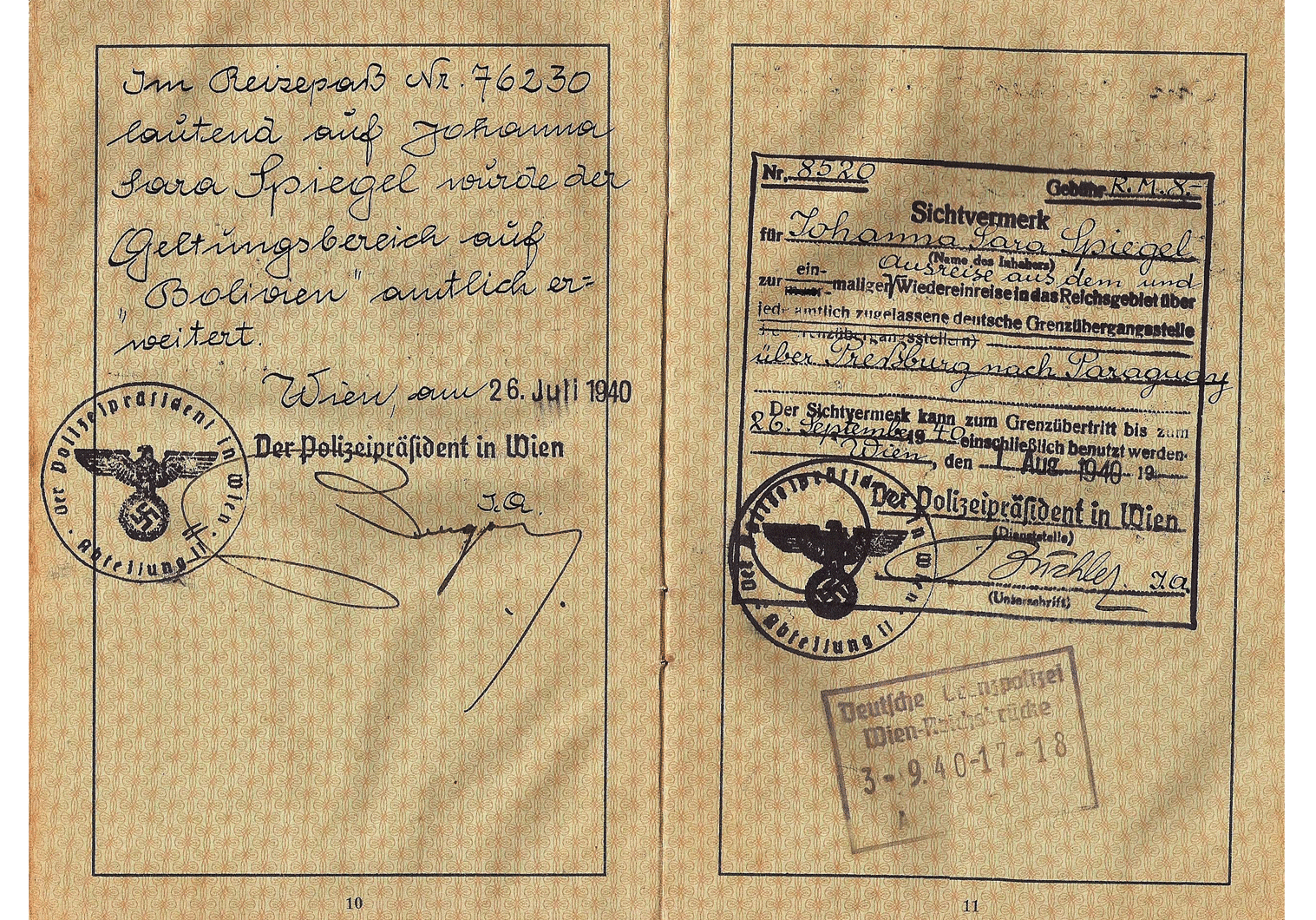

Strangely, their passports were amended for Bolivia, as seen on pages 4 & 10. Again, when looking inside the pages, there is no indication that they ever attempted to leave for that country. Their final exit visa, issued on August 1st 1940, and amendment with the routes indicated for Paraguay (no visa inside) via Pressburg (Bratislava) on pages 10-11 seem to have been issued by SS men Ernst Brückler & Anton Burger, and as mentioned above, were part of Adolf Eichmann’s staff.

They boarded a vessel (that was hired by Jewish officials working at the Palestine office Vienna), out of three (The Atlantic, the Milos and the Pacific). All three totaled about 3,500 passengers, with a large section not holding any proper immigration visas for Palestine: this would have dire consequences for them all once they arrived in November. The sisters left Vienna via the Danube border-crossing point of Wien-Reichsbrücke on September 3rd. Leaving Tulcia port about a month later. They passed Crete and Cyprus on October-November, and towards the 20th they reached Haifa port.

All the passengers were transferred, temporarily, to the Atlit detention camp off Mount Carmel (Palestine Police records indicate that the two sisters registered at the camp on the 27th). When the British authorities tried to forcibly transfer them all back to ships that were to take them to Mauritius Island, the Jewish underground intervened on November 25th, but with tragic results: A large explosive device was smuggled upon the transfer ship Patria, and a miss calculation in the amount explosives caused the vessel to sink taking down with her 250 deportees & British security forces personnel. Those who were on board the ill stricken ship were permitted to remain in Palestine as legal immigrants; whereas the others, on board the Atlantic, about 1,540 of them, were sent off to Mauritius, a British colony in the Indian Ocean, arriving at Beau Bassin. The men were interned at an old prison where as the women in metal huts nearby.

Their internment was registered as: Page 29 internee’s numbers 1362 & 1363.

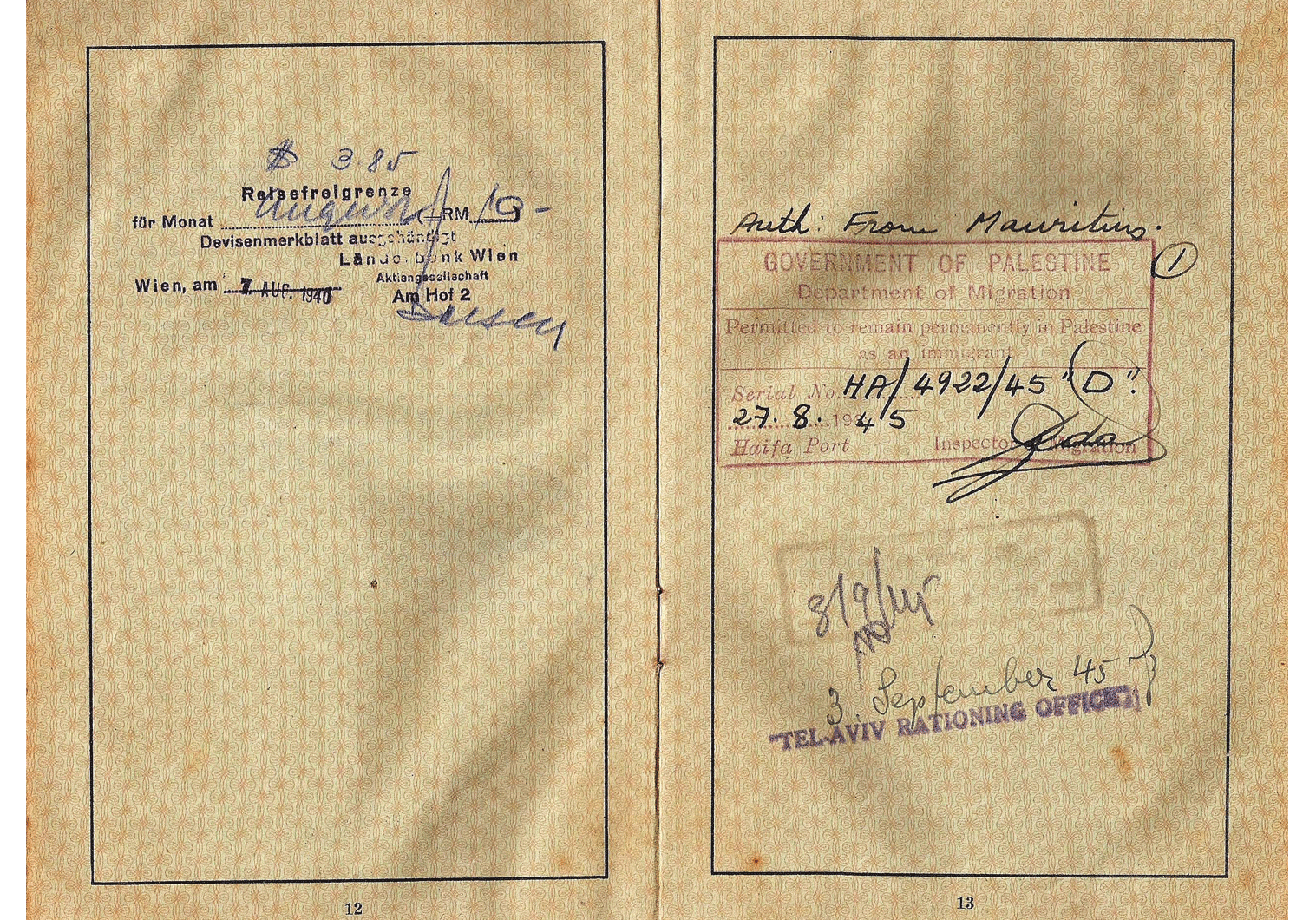

After the war ended, the authorities permitted all the remaining detainees to immigrate to the Mandate, arriving at Haifa port on August 27th, indicted inside their passports on page 13:

Authorization from Mauritius, immigrant SN number: HA/4922/45 D & HA/4921/45 C/L/S.

Overall 800 J stamped German passports from Vienna were brought in to the island at the end of 1940, with less than that being taken back with their holders to Haifa port after the war. What is truly remarkable, and needs to be mentioned here, is that the British released the poor refugees without any proper travel documentation, forcing them to re-use the wretched Nazi J stamped passports that they had when escaping. After the war, we can find the entry mark inside a document that was issued at the end by a regime gone extinct.

Here are some useful links:

Thank you for reading “Our Passports”.

Ross Nochimson

Well researched and informative article on the Mauritious Red J – a rare document indeed.