Bulgaria and the Holocaust

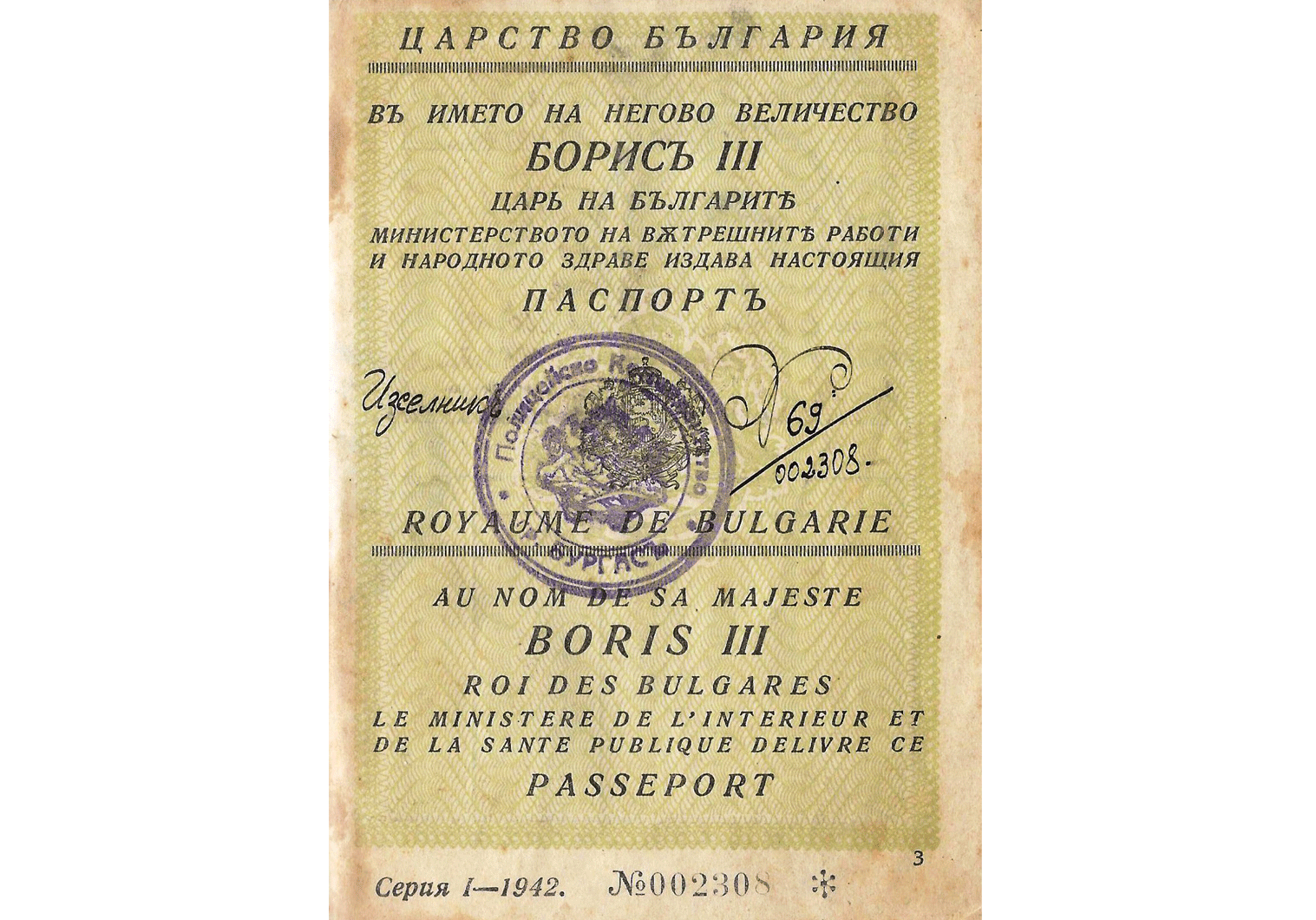

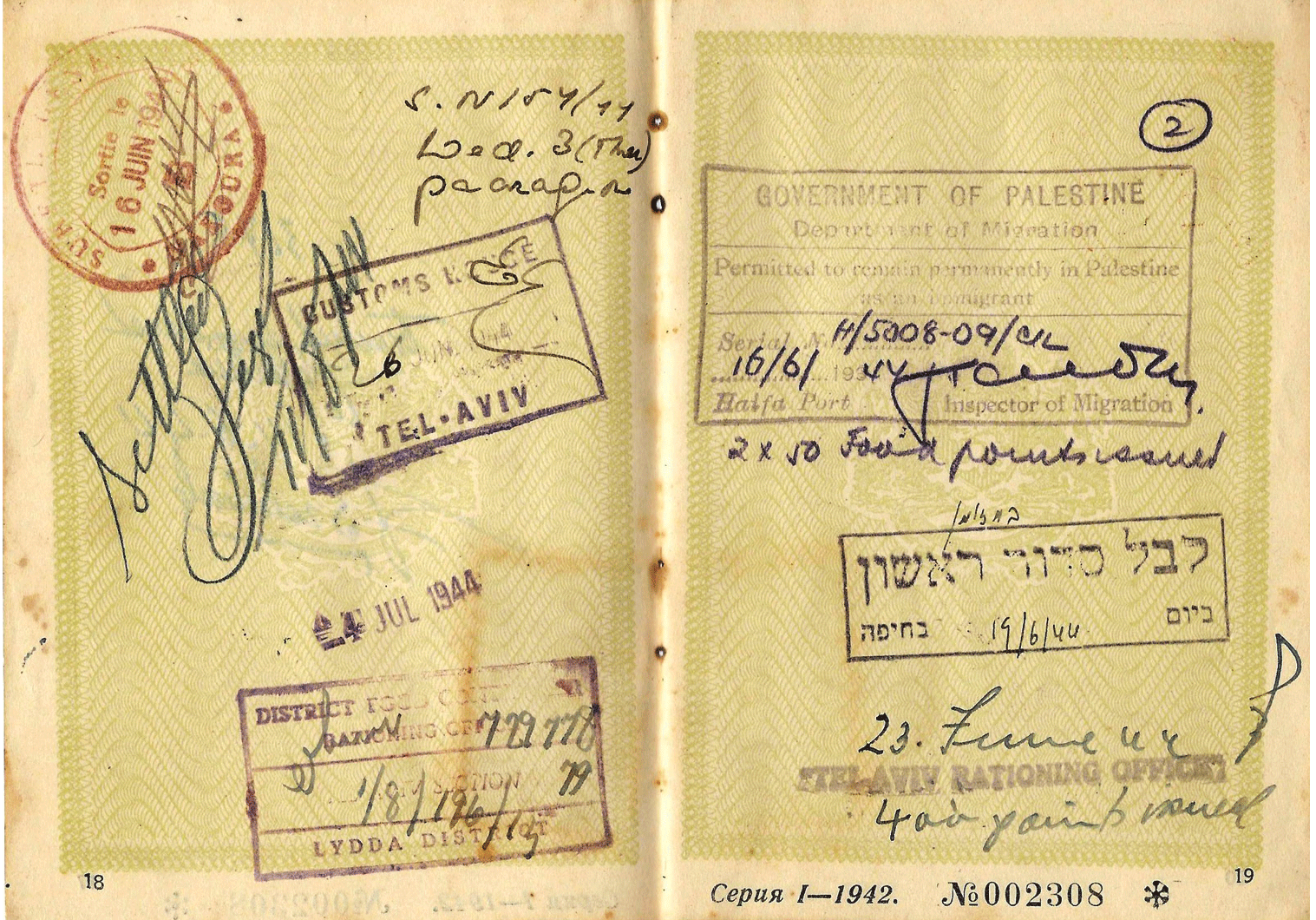

1944 issued passport for escaping to Palestine.

This is truly an amazing part of World War Two that not many are familiar with. Much has been written about the war and Holocaust with regards to western occupied Europe, Poland and the eastern states overrun in 1941, following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June, in what would be notoriously known as Operation Barbarossa.

When we try to recall and remember the atrocities committed during those 6 long years, we are always shocked and mixed with feelings of horror and disbelief of what one man can do to another fellow man. Our common sense and inner feelings do not want to accept and comprehend what the world went through over 70 years ago. Some of the events are too fantastic to acknowledge and accept, even though ample proof and material is presented to us: black and white reels of film, documents, photos, recorded testimonials and more.

The establishing of Ghettos, Einsatzgruppen units, gassing, hangings and shootings…Warsaw Ghetto, transport trains to the east, the invasion of Hungary and deportations…too many atrocities…too much horror…too much pain and suffering.

And still, there is another part of that dark side of mankind that is not spoken that often. Even when I was growing up as a kid and when we were taught about the war and the Holocaust, there is one chapter that was not told to us. A chapter that I learned on my own at a later stage in life, when I was learning and collecting: the miraculous way the Jews of Bulgaria escaped certain death and deportation to occupied Poland.

This is a story of one community that was practically, at the end, untouched by the angel of death; the story of an ancient community that was so close to being annihilated and at the end, at the last moment was saved: a one-of-a-kind event.

This is the story of Bulgaria and the war, Bulgaria and the Holocaust.

Art first, Bulgaria and its king Boris the 3rd wanted badly to avoid war and not repeat the same mistakes that were done during the previous Great War and earlier. The father of King Boris, Ferdinand I of Bulgaria, became the first Knyaz, Prince Regnant, in 1887 and formally the Tsar of Bulgaria in 1908. His reign ended in 1918, after unsuccessful attempts to conquer and expand his country’s borders, namely the costly and disastrous Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 and World War One, where the King joined forces with his former enemy, the Ottoman Empire, in order to gain land after the defeat and humiliation of those wars. The war ended with another defeat, unsuccessful attempts to halt the Allied army’s advances into Greece; it ended for Bulgaria with surrender and the loss of territory that was won 5 years earlier. In order to save the Royal Throne, Ferdinand abdicated in favor of his eldest son, who became Boris III of Bulgaria on October 3rd 1918.

As the 1930’s came closer to an end, and the clouds of war were getting darker by the day in Europe, King Boris wanted to prevent repetition of his father’s mistakes and avoid at all cost of dragging his country into another bloody war, or as he put it ” To prevent another Bulgarian soldier dying at war”. But this was not an easy task at all. 1940 saw both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union courting after Bulgaria, each one acknowledging the latter’s right to Romanian held territory of Dobruja. Bulgaria also had eyes on Macedonia and Thrace. Though Moscow wanted to sign a non-aggression pact with Sofia, Bulgaria was economically dependent on Germany when it came to foreign export, both countries were holding grievances due to the outcome of the First World War and only she could possibly be more sympathetic to King Boris’s territorial claims.

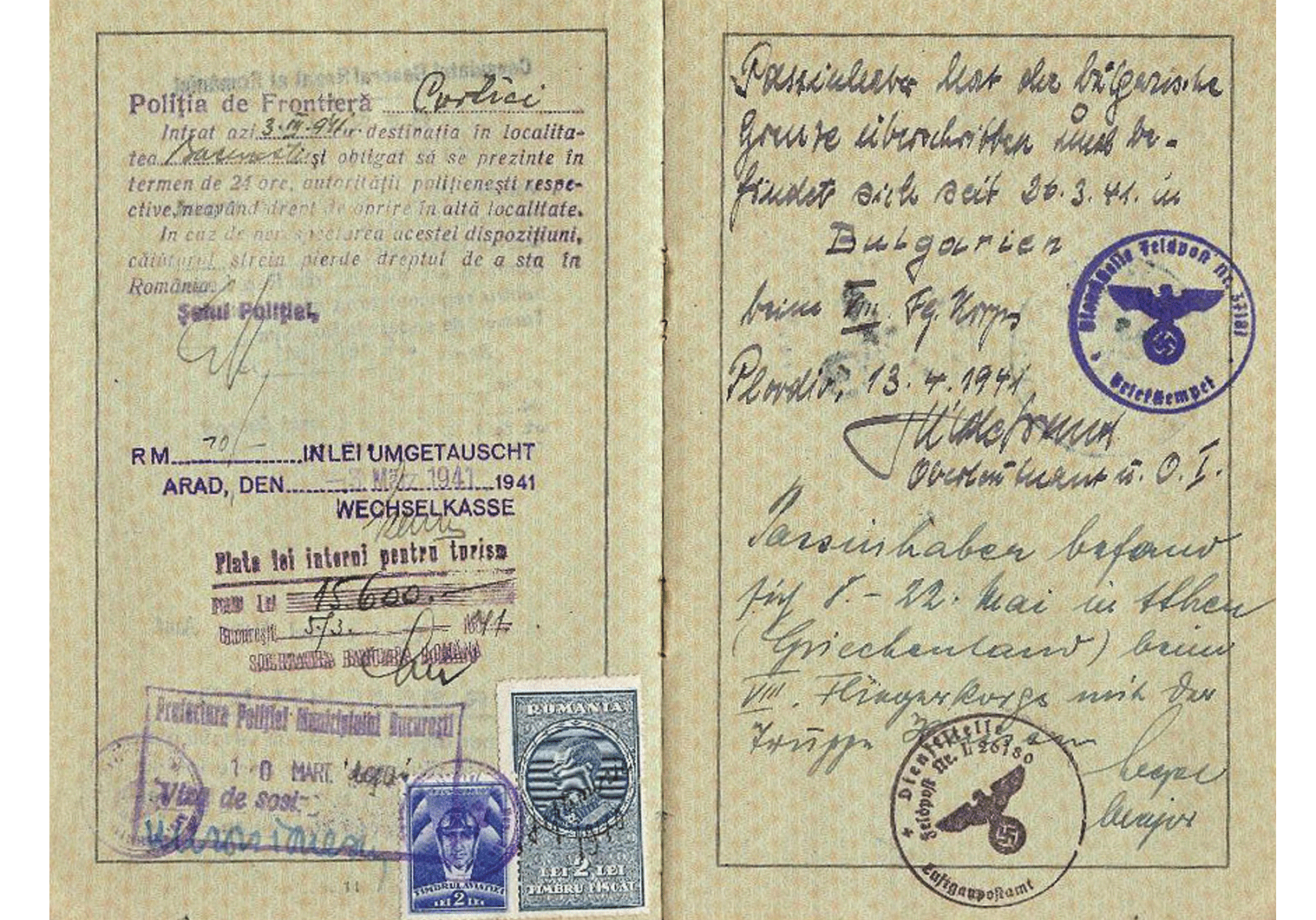

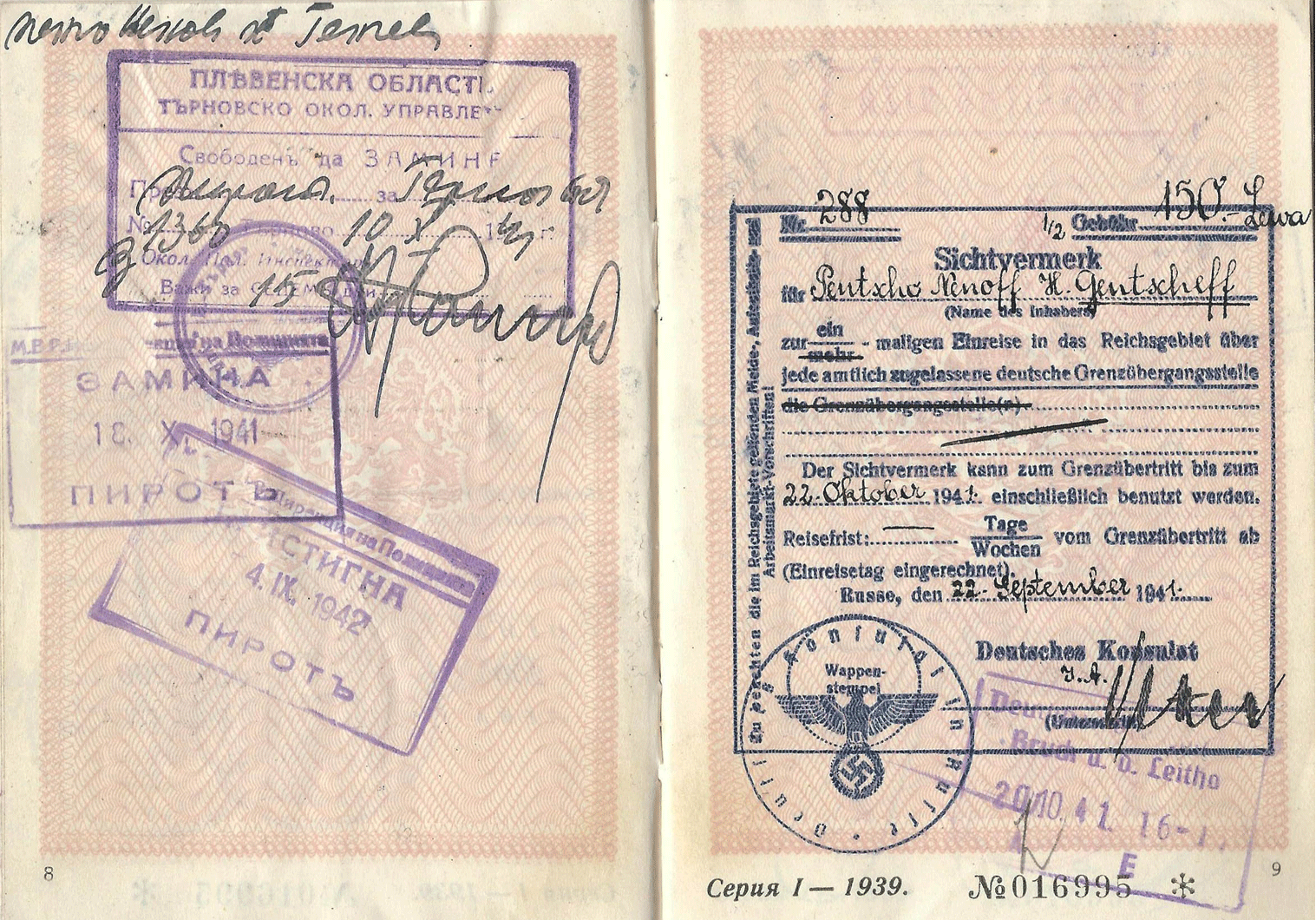

Thus, though managing to postpone any decision regarding the two, eventually, Sofia chose to side with Berlin and on March 1st 1941 signed the Tripartite Pact, being promised to gain back all land lost previously, in return for joining the Axis powers (Hitler wanted his troops to go through the country in order to attack Greece and later Yugoslavia) – see added image of a passport indicating inside that the holder joined the German army in Bulgaria during late March of 1941; German soldiers marched into the country following the signing of the above mentioned pact a few weeks earlier.

What is amazing about this country, and is important enough to mention in this article, is that Bulgaria was the ONLY Axis state to maintain diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union, with its embassy not far away from the Royal Palace and the Russian flag hoisted not far from the German flag; and the only country to actually sign a contract with Nazi Germany permitting the deportation of its Jewish population (and to their deaths in occupied Poland).

At first, the king and his country had no intention to go against their fellow Jewish citizens; anti-Semitism was alien to the country and the Jewish population had a very strong and patriotic relationship with their fellow Christian neighbors. Though initially not planned, the events of the war at the end pushed or led Bulgaria to adopt racial laws and decrees, similar to those used in Germany and by other Axis counties. Sofia established a Commissariat for the Jewish Problem/Affairs led by rabid anti-Semitic former lawyer named Alexander Belev, who was appointed by the Interior Minister Petar Gabrovski. Belev was even dispatched to Berlin to closely learn about the 1935 racial Nuremberg Laws in order to implement the same back home, he was sent on December 29th 1941 and returned back on February 14th the following year. His offices housed a staff of 113 and had 4 main departments: administration, finances, public official work and economic activities and agents.

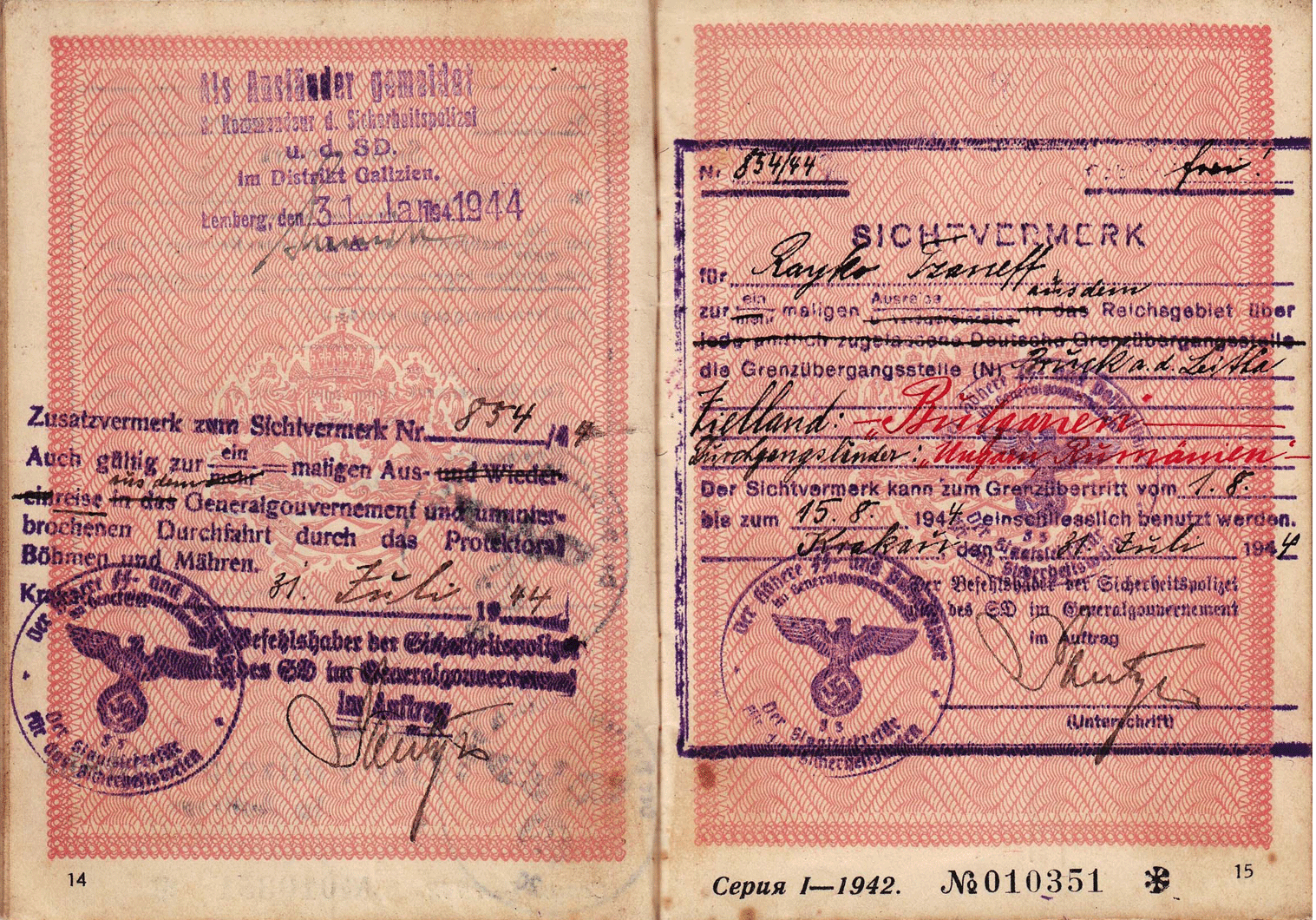

Closer ties with Germany led to some changes and the deepening of ties between the countries, also with relation to the Jewish Question in Bulgaria: In July of 1941 a new ambassador was sent to Sofia, Adolf Heinz Beckerle, former SA-Obergruppenführer and a rabid anti-Semite. A year and a half later Sofia would receive another important addition to its German representatives already in the country, high ranking SS official personally sent by Adolf Eichmann to supervise the deportation of Bulgaria’s Jews, SS Hauptsturmführer Theodor Dannecker. As mentioned above, Bulgaria was the only country that singed a deportation agreement with Nazi Germany, and this was done so on February 22nd 1943, jointly singed by both Dannecker and Belev (a meeting between Belev, Dannecker and Gestapo attaché Adolf Hofmann that was held on February 2nd led to the agreement being formed and singed several weeks later). The agreement was for deportation of 20,000 Jews (12,000 from newly gained territories and the remaining amount to be shipped from Sofia, mainly influential and rich Jews). March 2nd saw the official governmental deportation decree being put into place, decree number 127 entrusted the Commissariat of Jewish Affairs to allow, with German consent, the deportation of 20,000 Jews from the country. A previous decree numbered 116 stripped all the Jews of their rights and citizenship once being deported, thus allowing the government to confiscate all possessions, cash, land and material. Prior to these events, Bulgaria issued the Law for Protecting the Nation at the end of January 1941, similar to the German Nuremberg Law of 1935. Jews were also ousted from the army but put into special Jewish work battalions, Jews were not allowed to marry non-Jews, not allowed to hold non-Jewish names, not allowed to serve in official or public offices, change address or live in the capital. Not allowed to run any business, such as theaters, companies, or hire Bulgarian workers or maids and immigration to Palestine was forbidden and more (see image of a Bulgarian issued passport used by a non-Jew to travel on work in occupied Poland). The list is long.

King Boris had several meetings with Hitler, the last one taking place on August 14th 1943: This meeting did not go well, the king refused to send troops to fight the Red Army and also to deport his Kingdoms Jewish population. His refusal caused a great rift between the two leaders, making Hitler furious at his “lack of loyalty and commitment to the cause”. The meeting ended with agreement that Bulgarian Jews will not be deported and kept for labor tasks, such as road maintenance.

Shortly after returning home, the King passed away from heart failure on August 28th (some suspected that the king was murdered and was given the same poison used on Greek Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas – a slow poison taking weeks to work and leaves blotches on the victims skin before his death). The kings son Simeon took over his father, but was a minor aged 6, thus the country was controlled by the following three appointed regents: Prince Kyril of Bulgaria (uncle), Prime Minister Bogdan Filov and Lieutenant General Nikola Mikhov (all three were executed on February 1st 1945). Bulgaria was invaded on September 9th 1944 by the Red Army after Moscow declared war on her 4 days earlier. All three were arrested following a Soviet supported coup (the fate of Alexander Belev was swift and brutal: years after the war ended it was revealed that he was discovered by a group of partisans at the train station of Kyustendil and arrested. He was sent to Sofia and escorted by a Jewish partisan who executed him after they left the town; his body was dumped at the side of the road; all this shortly after the Soviets entered the country on September 9th 1944).

March 9th 1943:

This date has importance and significance when one talks about the Holocaust and Bulgaria.

This is the date that all Bulgarian Jews will remember in infamy; the date that they avoided deportation and certain death.

Liliana Panitza was a young and attractive woman who was working at the Commissariat for Jewish Affairs in Sofia. She was in her twenties and the secretary of the ministry’s head – Alexander Belev. And it was she who decided to warn the Jewish community of the coming planned deportation in the days to come: she confided with her family friend Dr. Nesim Levi, well known Jewish lawyer from the capital and vice of the Jewish community as well, and it was he who reported of the planned deportation of Jews from Thrace and Macedonia to Poland to the rest of the members of his community. And as planned and arranged by the authorities, the “actions” began on March 4th, starting with the Thracian town of Gyumurgina: 863 women, children, the elderly and the young, all were within 24 hours put onto trains to take them to the death camp of Treblinka. The Commissariat even prepared in advance transit camps for the deportees:

- Dupnitsa (Bulgaria)

- Gorna Djumaia (Bulgaria)

- Radomir (Bulgaria)

- Skopje (Macedonia)

- Pirot (Serbia)

All deportees would be sent to the port of Lom, sail via the Danube all the way to “meet” the Germans, who will transport them to occupied Poland. The transports began on March 18th-19th from the main Bulgarian transit camps and from the 22nd-23rd and the 29th for the Jews deported from Macedonia. All were transported to the harbor at Lom, on the Danube, and from there via boats towards Vienna. At the end, close to 12,000 were sent to their death (4,221 Thracian Jews & 7,122 Macedonian Jews); then came the turn for Bulgaria’s Jews to meet the same fate.

This at the end would not be their fate: King Boris refused to deport his Jewish population to German controlled Poland, since by this time some information regarding their would-be-fate was known: the Kings decision to abort the deportation came around noon on the 9th, where an order was given to the Interior Minister who conveyed it to Belev (it is reported that the Commissar for Jewish Affairs took the order very badly and resigned, but withdrew it upon protest and pressure from his colleagues and the Germans). He refused, as mentioned above, to comply with Hitler’s demands and thus with his persistent refusal, together with Dimitar Peshev, pre-war Deputy Speaker of the National Assembly of Bulgaria & Minister of Justice (1935-1936), Stefan I (Head of the Bulgarian Church) and others, close to 50,000 of Bulgaria’s Jews were saved.

The passport:

During the war, immigration out of Bulgaria to British Palestine was forbidden. But this changed towards the end of 1943 and the beginning of 1944, when it was clear already that Germany would lose the war and Sofia, like most of the Balkan capitals began to look for ways to separate themselves from their alliance with Nazi Germany and search for ways to contact the allies and change sides. ‘Feelers’ to neutral diplomatic legations were being sent, such as the Swiss and the Vatican. Eventually the British permitted immigration certificates to be issued and sent to Budapest, Bucharest and Sofia: List compiled in Palestine and in the Balkans had names of Jews that would receive such permits, with confirmation being sent to the representatives of the Swiss government, Vatican and British PCO in Istanbul (headed by Arthur Whittall). 7,000 confirmations sent to Bulgaria, 18,500 to Hungary and another 9,000 to Romania.

The crossing of borders – or escape routes – was mainly done illegally and it had 2 main routes that were the “favorite” and used by Jewish refugees and smugglers alike:

- Western Europe: from Germany and Austria westwards to Belgium and Holland. Following the occupation of those countries, the routes changed to France, Switzerland and Spain.

- Eastern Europe: Poland to Slovakia (after the transports to the death camps ceased in October of 1942) with the destination of Hungary – which was a safe haven for refugees during the war up to March of 1944. Another optional route was from Poland to Romania, which was stable up to 1945, after the 1940-1941 pogroms and deportations ended (escape to Italian controlled territory was also chosen, since the Italians were more humane and not rabidly fanatic when it came to the treatment of the Jews).

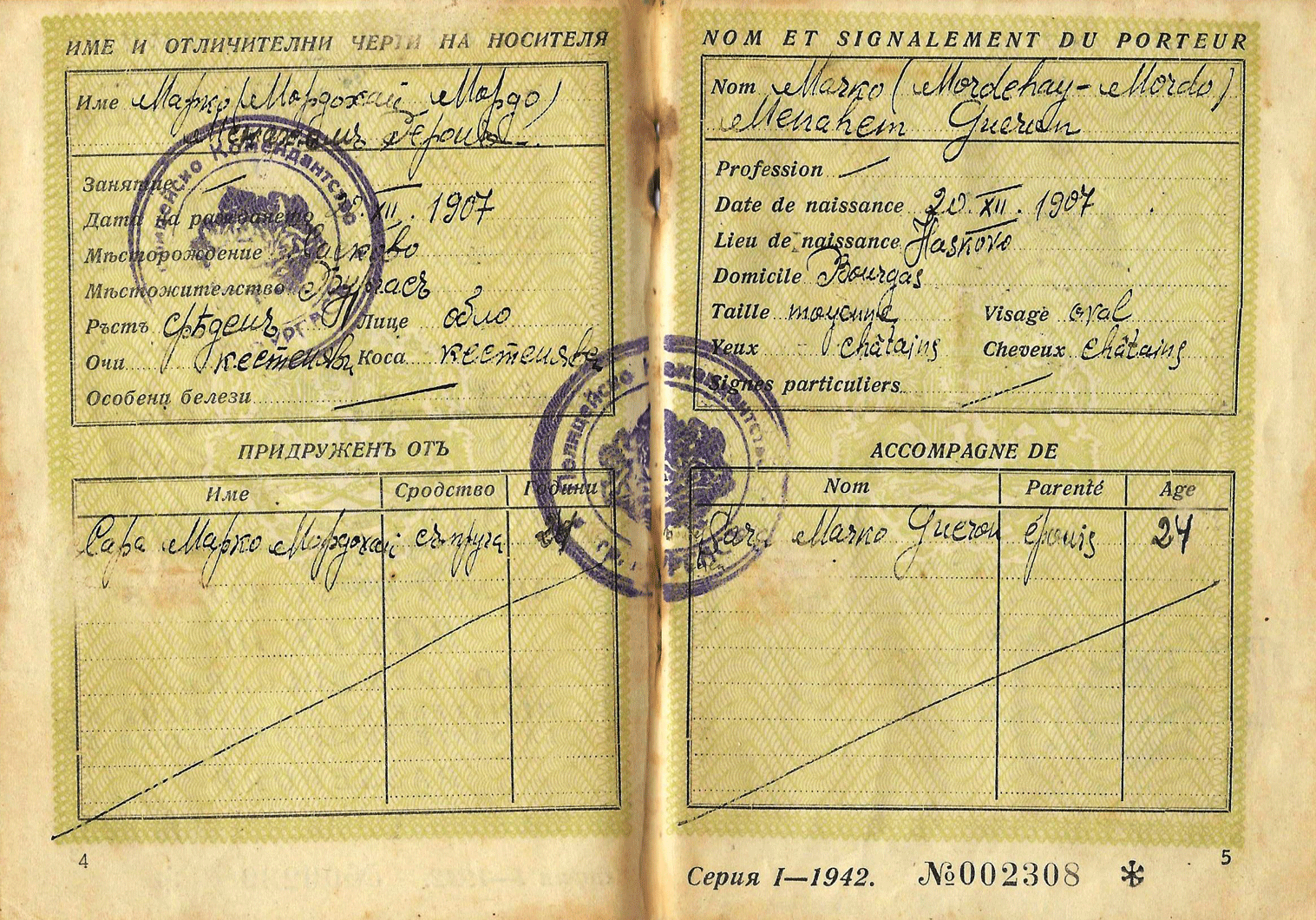

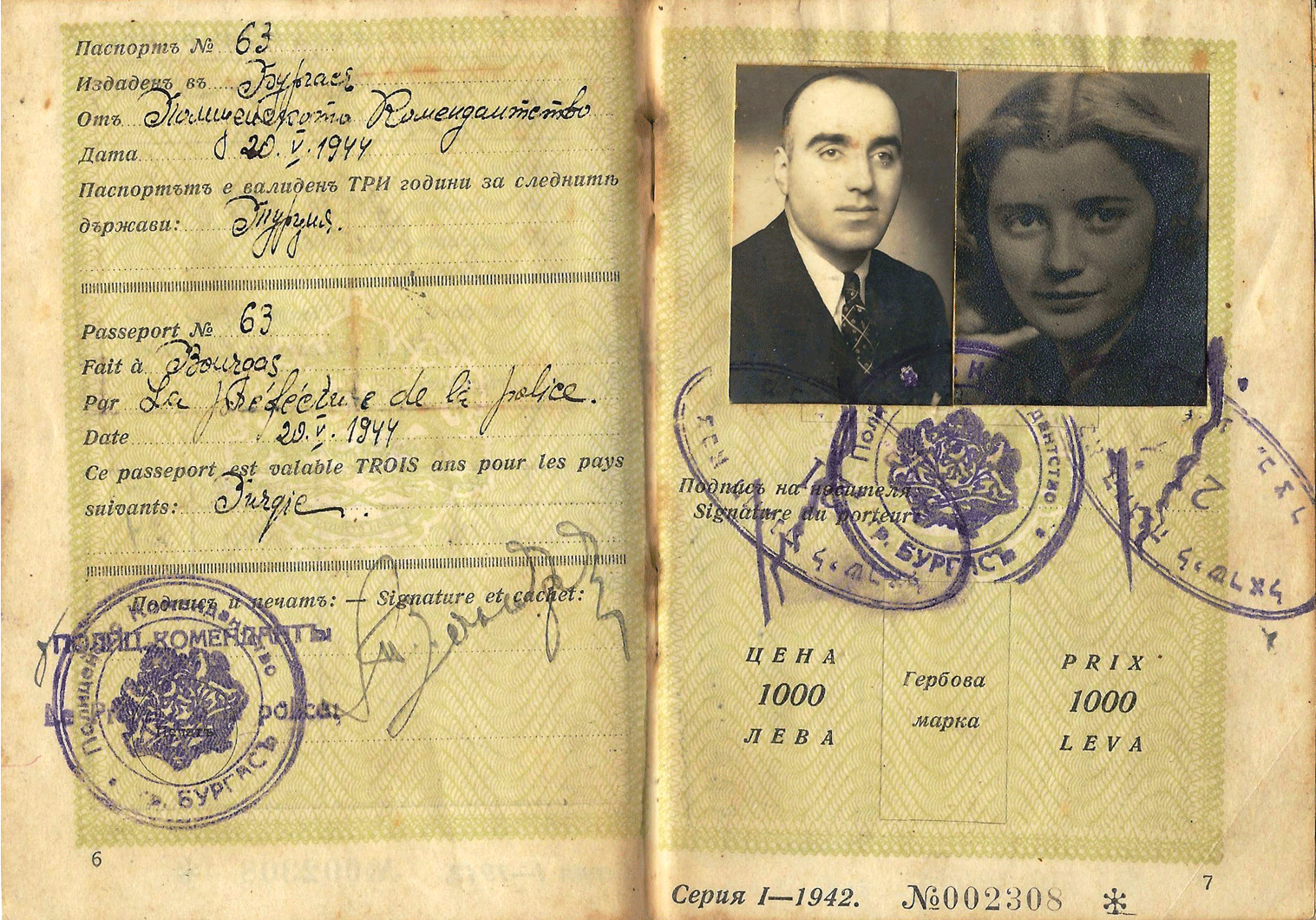

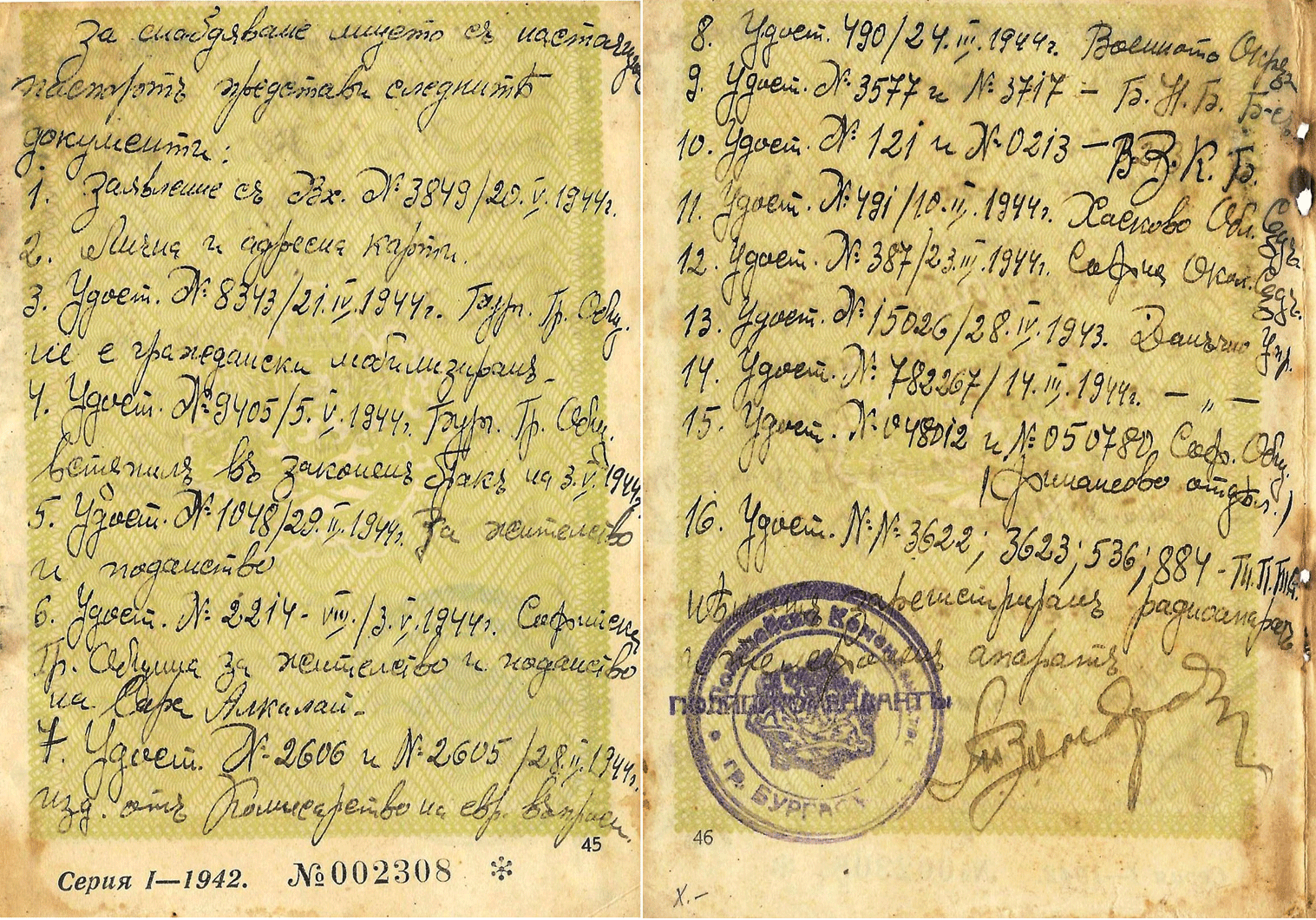

Bulgarian passport No. 69/002308 was issued to husband and wife Marko and Sara (nee’ Alkalay) Gueron at Burgas on May 20th 1944. The passport was issued with a tremendous large amount of certificates and permits that were required by the Burgas police authorities, for example: ID card, exemption from military (Jewish work battalions), proof of marriage, permits by the Commissariat for Jewish Affairs, Burgas branch of the Bulgarian National Bank, Sofia District Court, Sofia Municipality for citizenship and nationality of Sara Alkalay, from the local Military Command, telephone & radio registration permits and more (all these were added by hand at the back of the passport when issued).

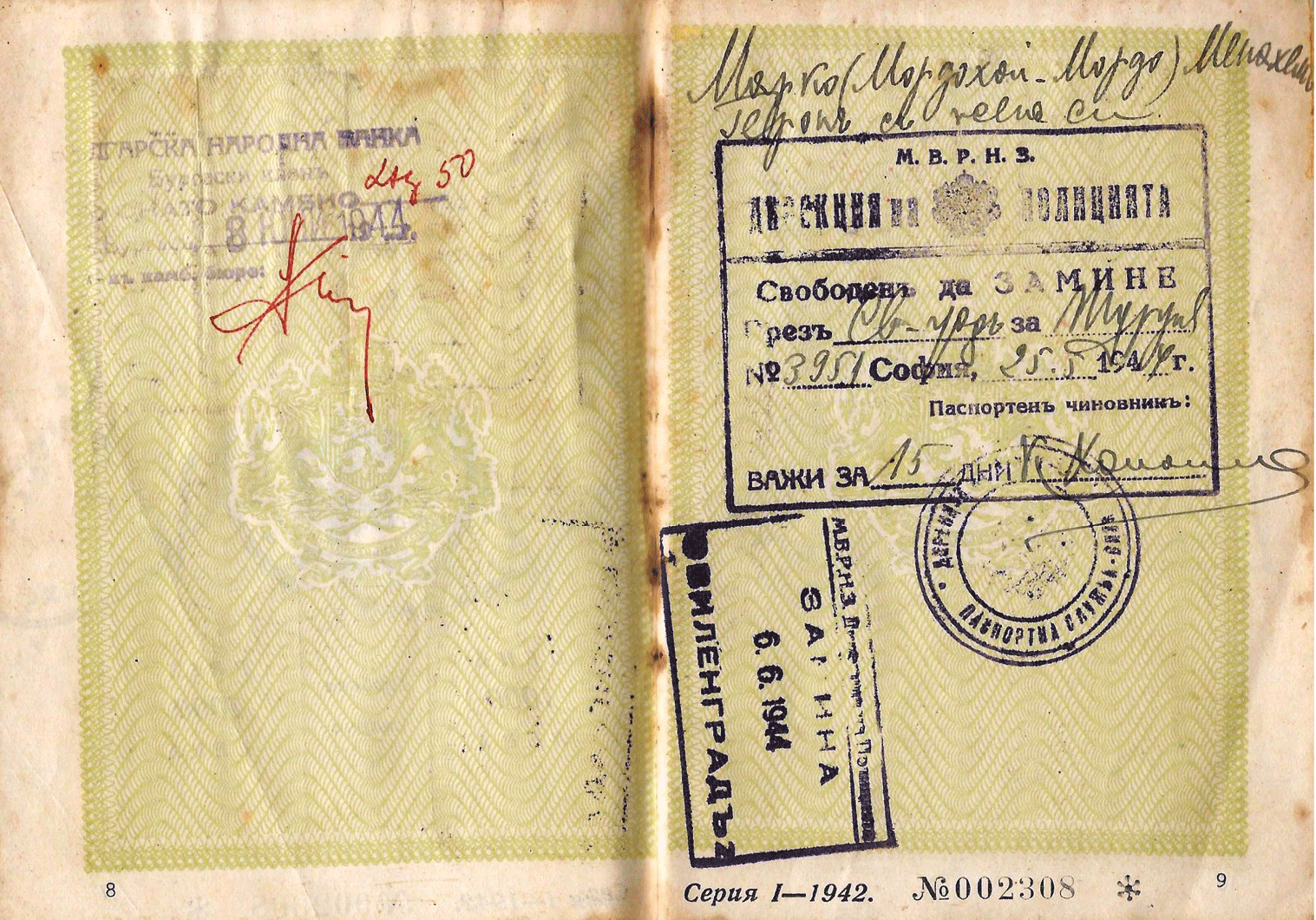

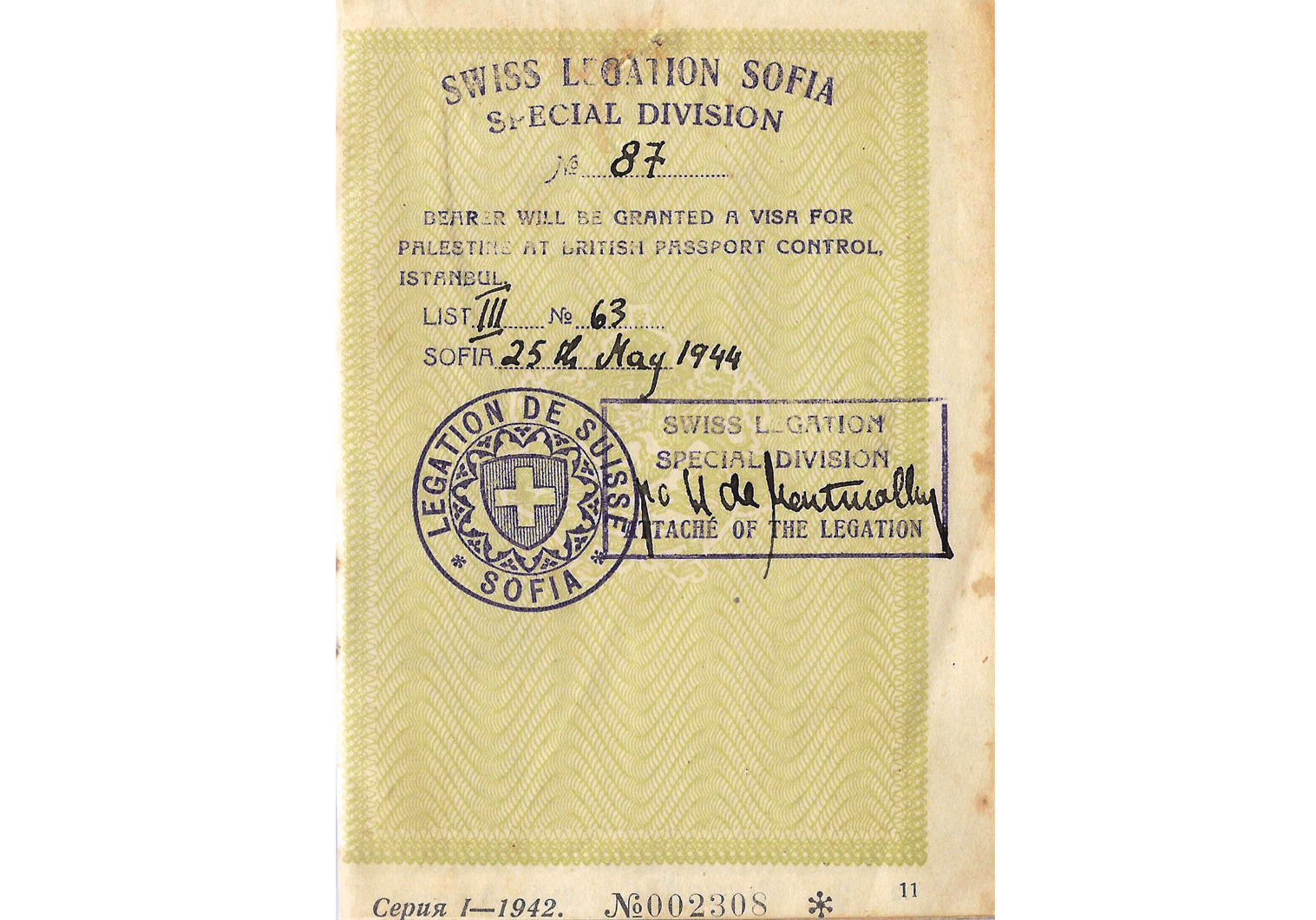

Exit permit number 3951 was issued on May 25th at Sofia, followed by the important visa for British Palestine that was issued by the Swiss legation in Bulgaria who was representing foreign interests in the Balkans. Important note: The visa clearly indicates that the “Bearer will be granted a visa for Palestine at British passport control, Istanbul” – in this case, it would be MI6 agent Arthur Whittall, acting senior PCO in Turkey. Visa number 87 was issued by the Special Division at the Swiss Legation by Henry de Montmollin, aged 29, who was attached to the foreign interests section of the diplomatic mission.

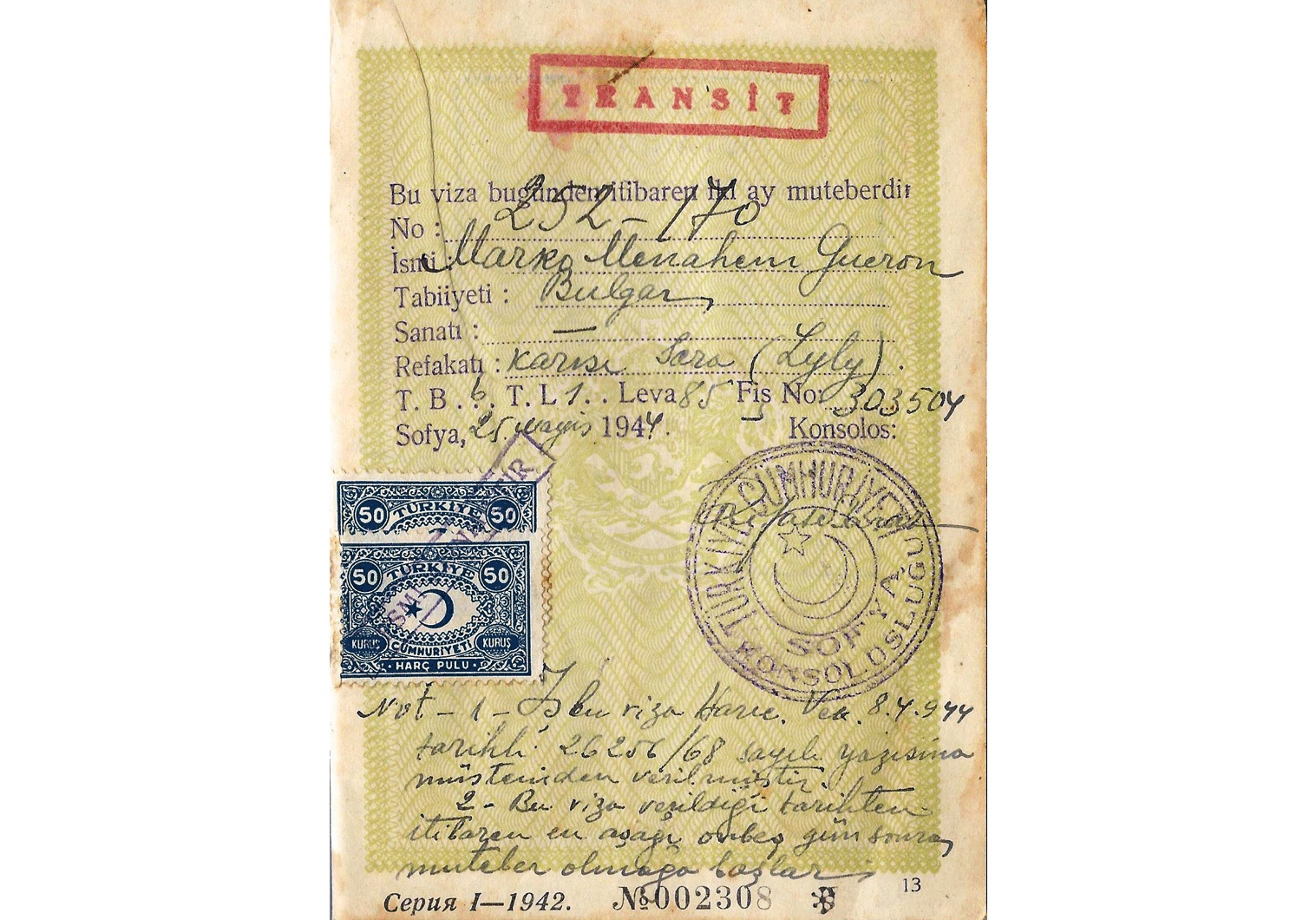

The same day the Turkish transit visa, number 252-170, was issued for the explicit journey to Turkey (the Swiss and Turkish legations received British immigration permits sent by the British PCO in Istanbul; such permits enabled the refugees to apply and receive the desired Turkish transit visas).

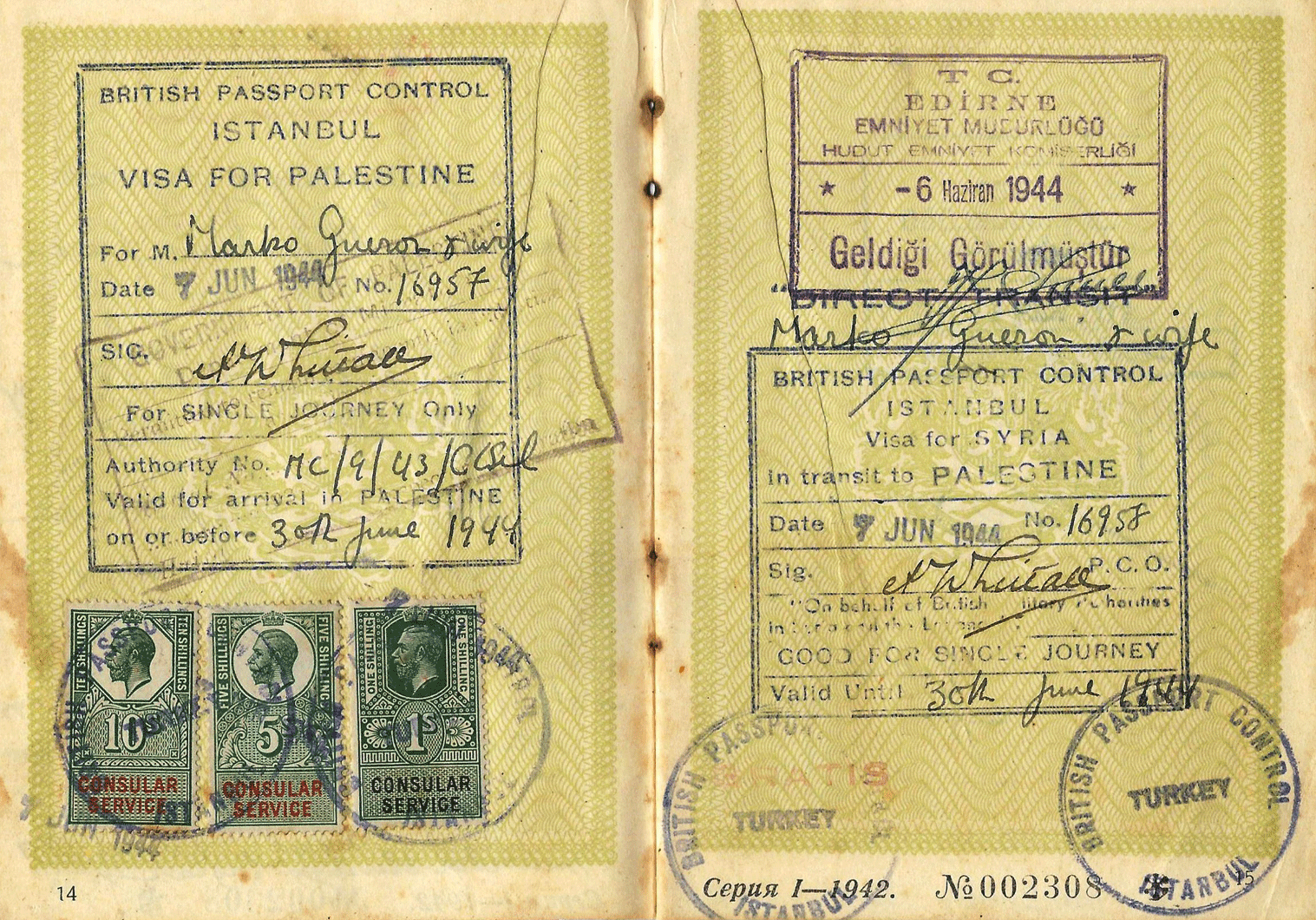

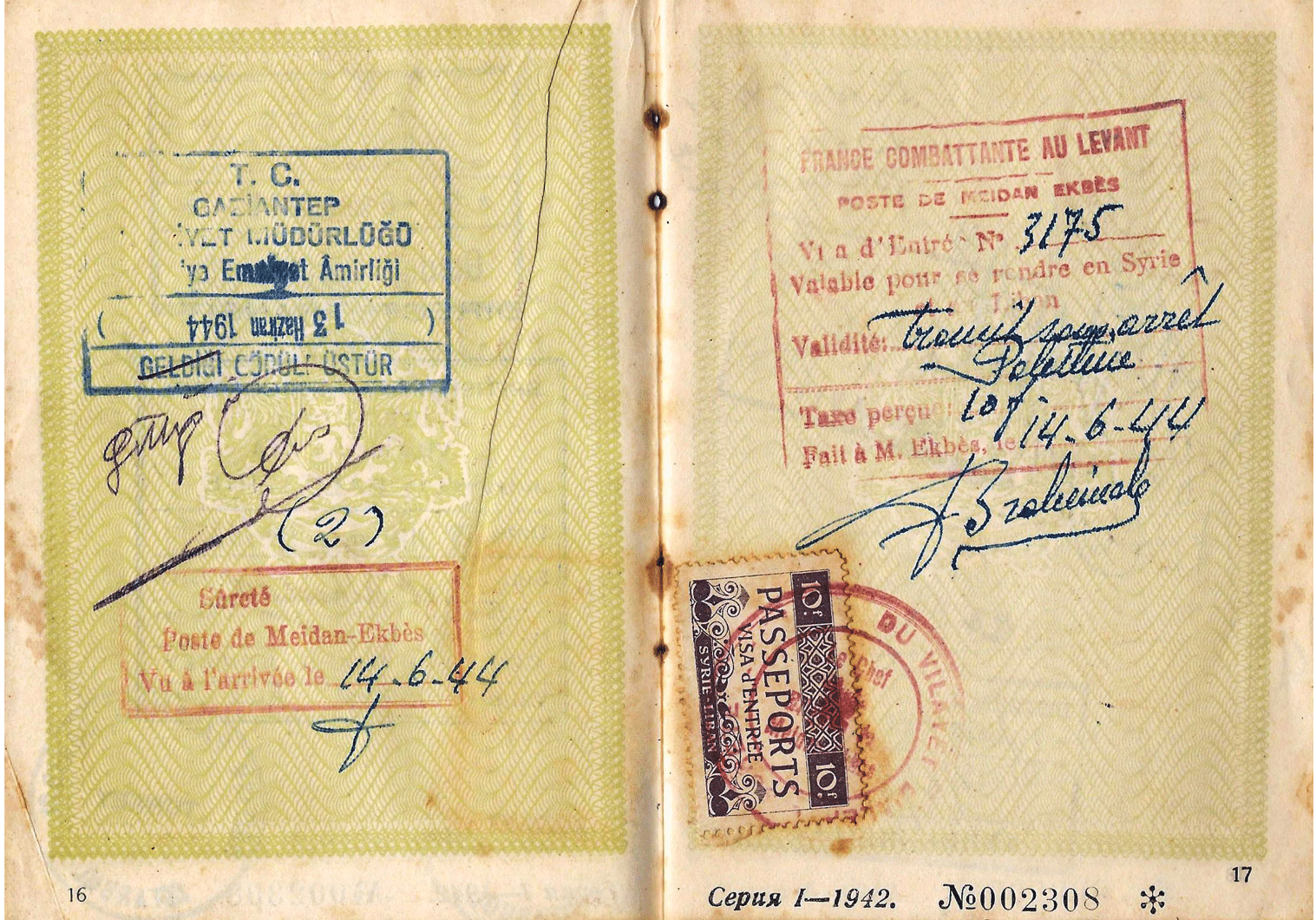

The couple left Burgas on June 6th and travelled south were they left Bulgaria via the central border train station of Svilengrad (Свиленград), which was also jointly guarded by both Bulgarian and German authorities, from there crossing into Turkey via Edirne the same day. Once in free in Turkey, with great relief, they proceeded to the British PCO in Istanbul who issued them the transit visas through Syria; visas numbered 16957 & 16958, and as indicated inside “On behalf of British Military Authorities in Syria and the Lebanon“. The couple left Turkey into Syria via the border crossing point of Meidan-Ekbes on June 14th, after exiting the Turkish side at Gaziantep via train. An attractive addition is the French visa stamp that was applied inside the passport. Two day later, they entered Palestine via the Lebanese border crossing of Naqoura. Official entry stamp was granted by the British immigration authorities at Haifa, the same day.

Such efforts should not be forgotten and we must all remember that at times of need we must not lose our humanity and work jointly together to assist and help the weak and those that stare death in the face. The tireless work that all sides contributed at the end to the safe arrival in Haifa, and from there onwards they were in the warm hands of the Jewish Yishuv, aiding them with all the required support, especially the moral and emotional support that they lacked throughout the war back in their hostile home.

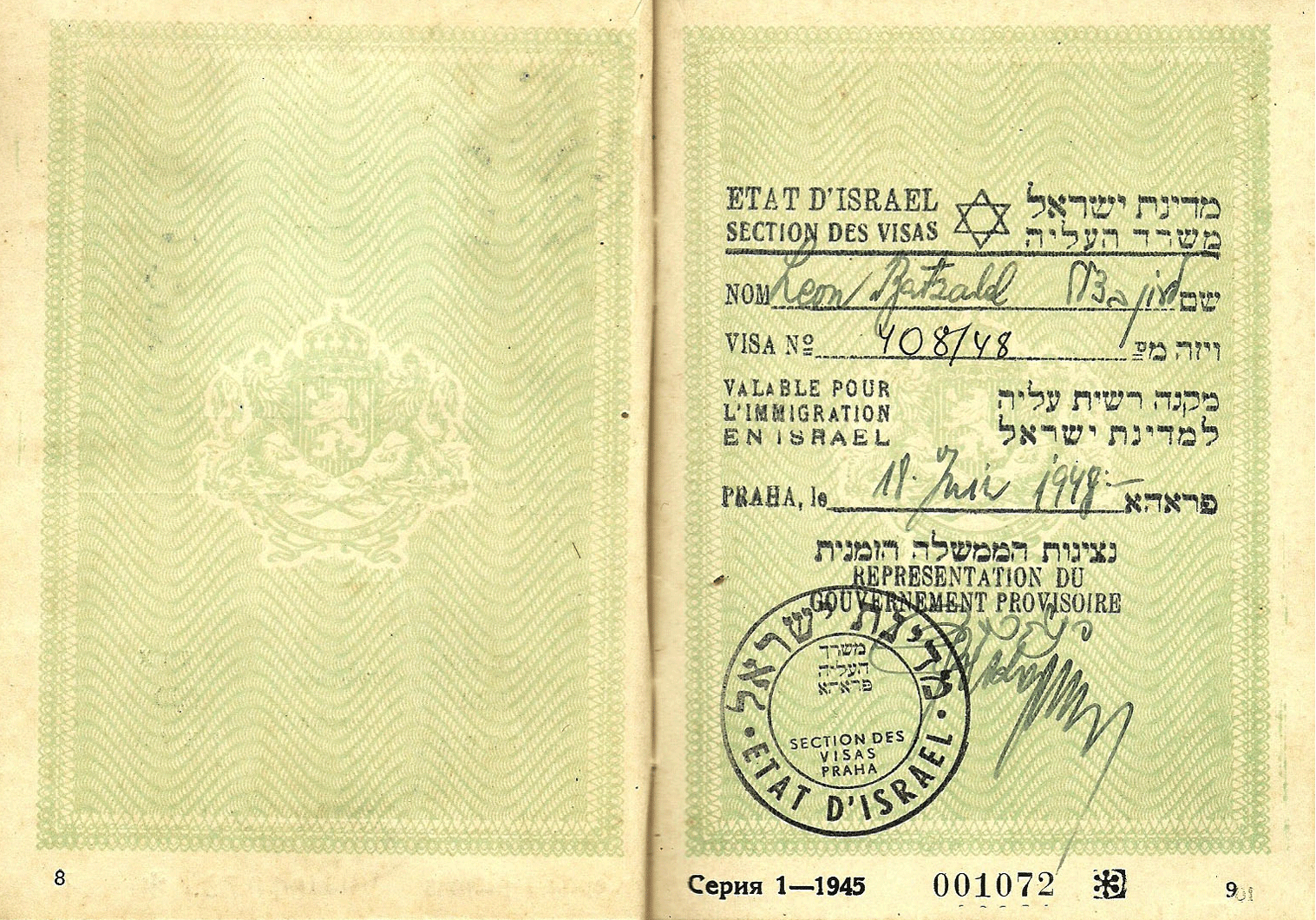

Have added additional images of other Bulgarian war-time used passports and one dating from June 18th 1948 that was issued at Prague, with the entry visa as immigrants to the new State of Israel, the rare and early visa issued by the interim government, founded a month earlier in May.

Thank you for reading “Our Passports”.