One of the last Polish passports from Lithuania

1939 issue from Kaunas.

World War Two passports are a very important source of information for us collectors and historians.

Written testimonials in form of diaries and letters can offer us the deepest insight and witness accounts of the events that unfolded every day throughout the war. The feelings and facts contribute immensely to the images and films that survived. To all of these important contributions we can also add the passport or travel document as well.

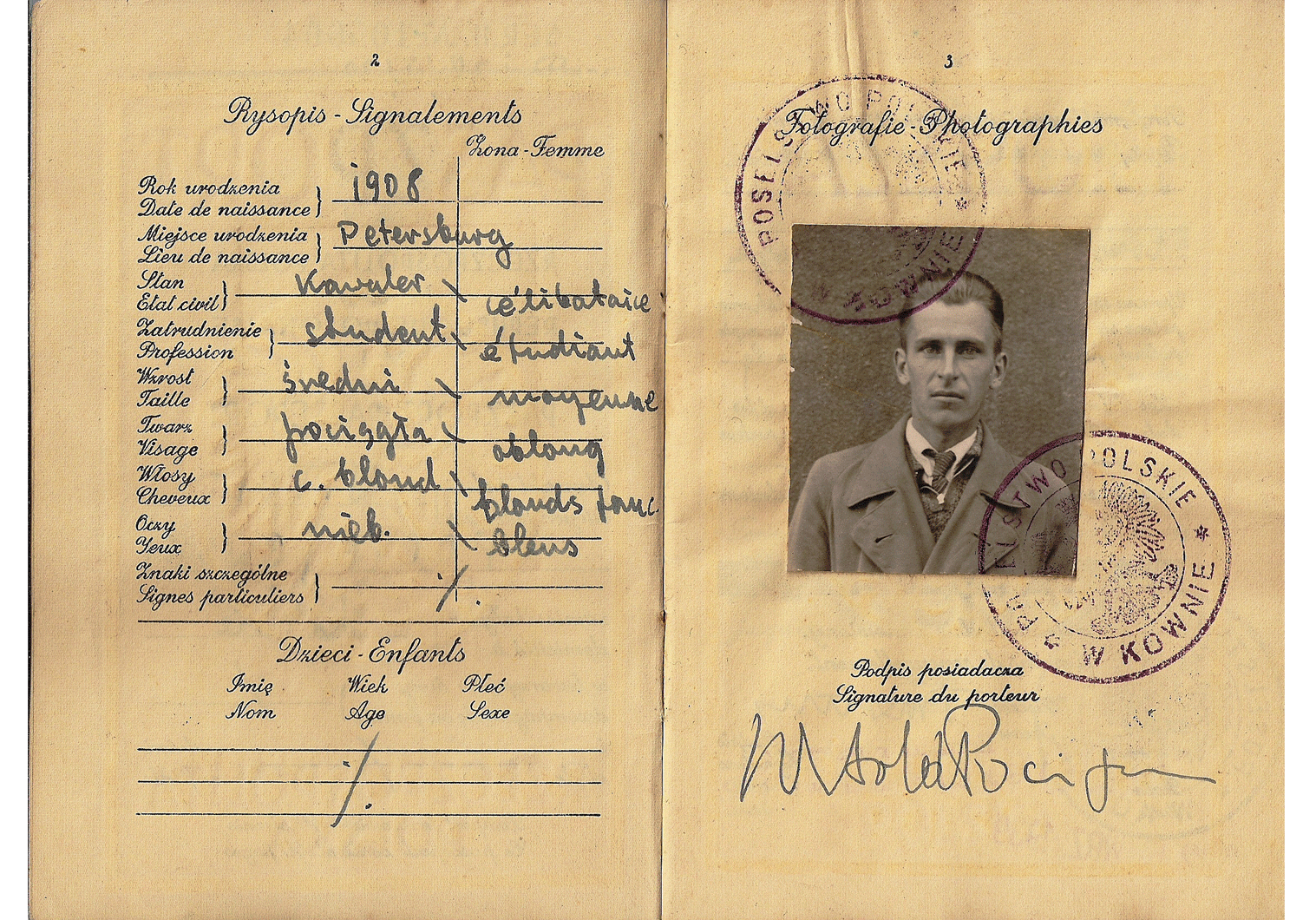

The passport sheds personal information, such as physical features and profession to the victims or survivors of the war. After understanding and feeling how the individual, who once held this document in his hand, most likely his most cherished valuable possession at the time, may have looked like, his background, we can then learn and visualize in our minds the routes that he or she took, with or without his family, in order to escape the war and its horrors.

An imaginary map is unfolded in front of our eyes. The map has a starting point. It also has an end: instinctively, we try to seek and find hope, so we rush forward, eyes scrambling on the map, to try and find its end, the final destination where the passport holder managed to reach. At times we can find it on the West or the East, when we realize that he or she landed safely in some neutral or allied controlled port, there is a sigh of relief. We are content and pleased to find out that one has reached to the safer and calmer beaches at the end. But, sometimes, the end picture is not as we would have hoped and wished for.

The West included countries in the north & south Americas, or neutral European countries, such as Sweden, Switzerland, Spain or Portugal, no matter how few they were at the end; and the East, such as the relatively “calmer” port city of Shanghai or further even to Australia.

One of them neutral or safer destinations, at least at the beginning of the war, was the small Baltic state of Lithuania. Regardless of the events that engulfed this small country in 1939, 1940 and then in mid 1941, for the first 2 years of the war, it was a safe haven, of some sort, for thousands of refugees, Jewish and non-Jewish.

The temporary capital of Lithuania, Kaunas, housed several thousand refugees from neighboring Poland who fled during the first weeks of war, in the month of September.

The local authorities began even printing a special “Refugee War Certificate”, which was also an identity document that could be used to leave the country. Those who were lucky managed to do just that: before and AFTER the Soviet invasion and occupation of the county in mid 1940, and then later on before June of 1941, the German invasion from the east.

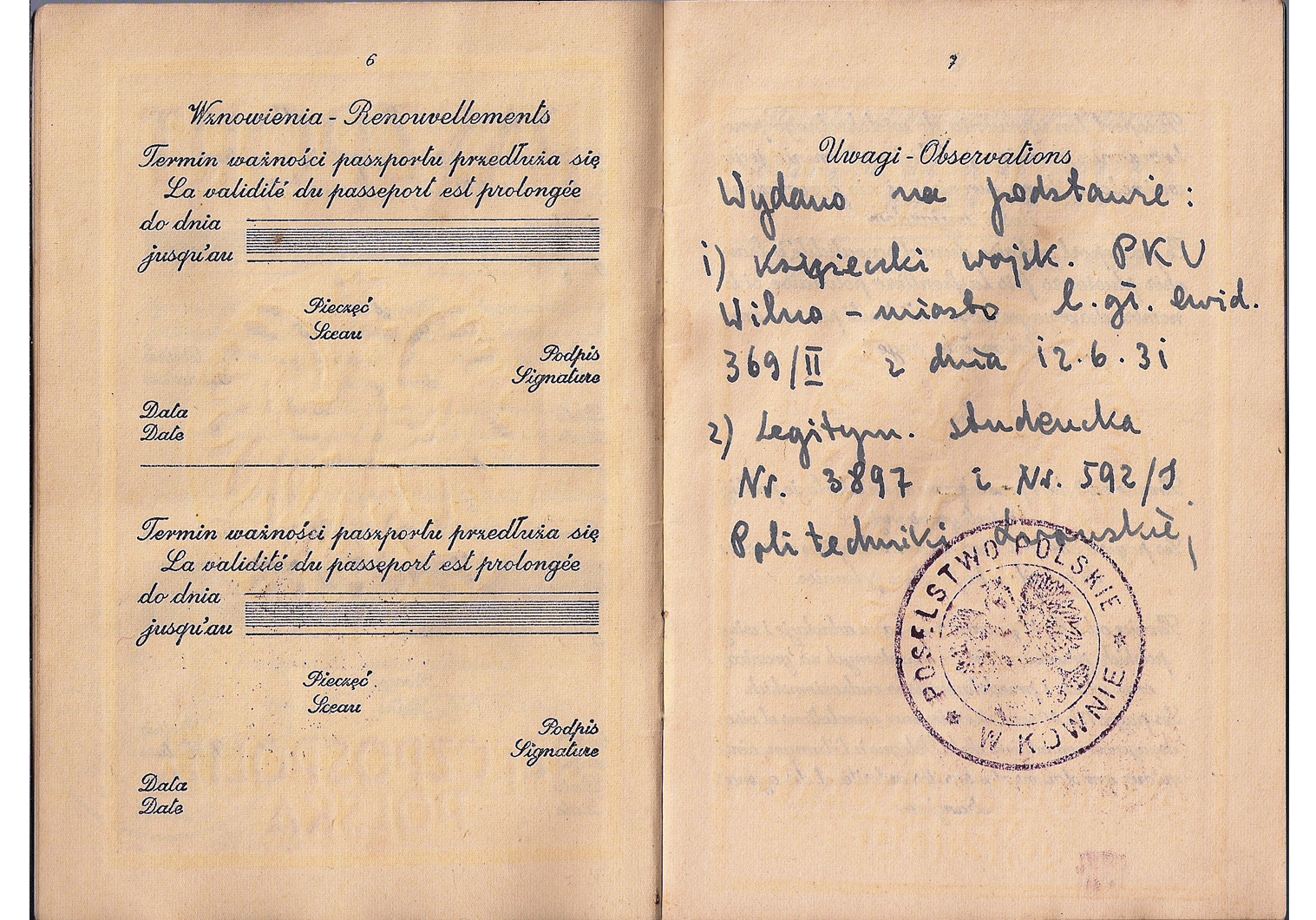

One issuing body that contributed to the refugee’s plight, by issuing emergency travel papers, was the Polish diplomatic legation in the capital.

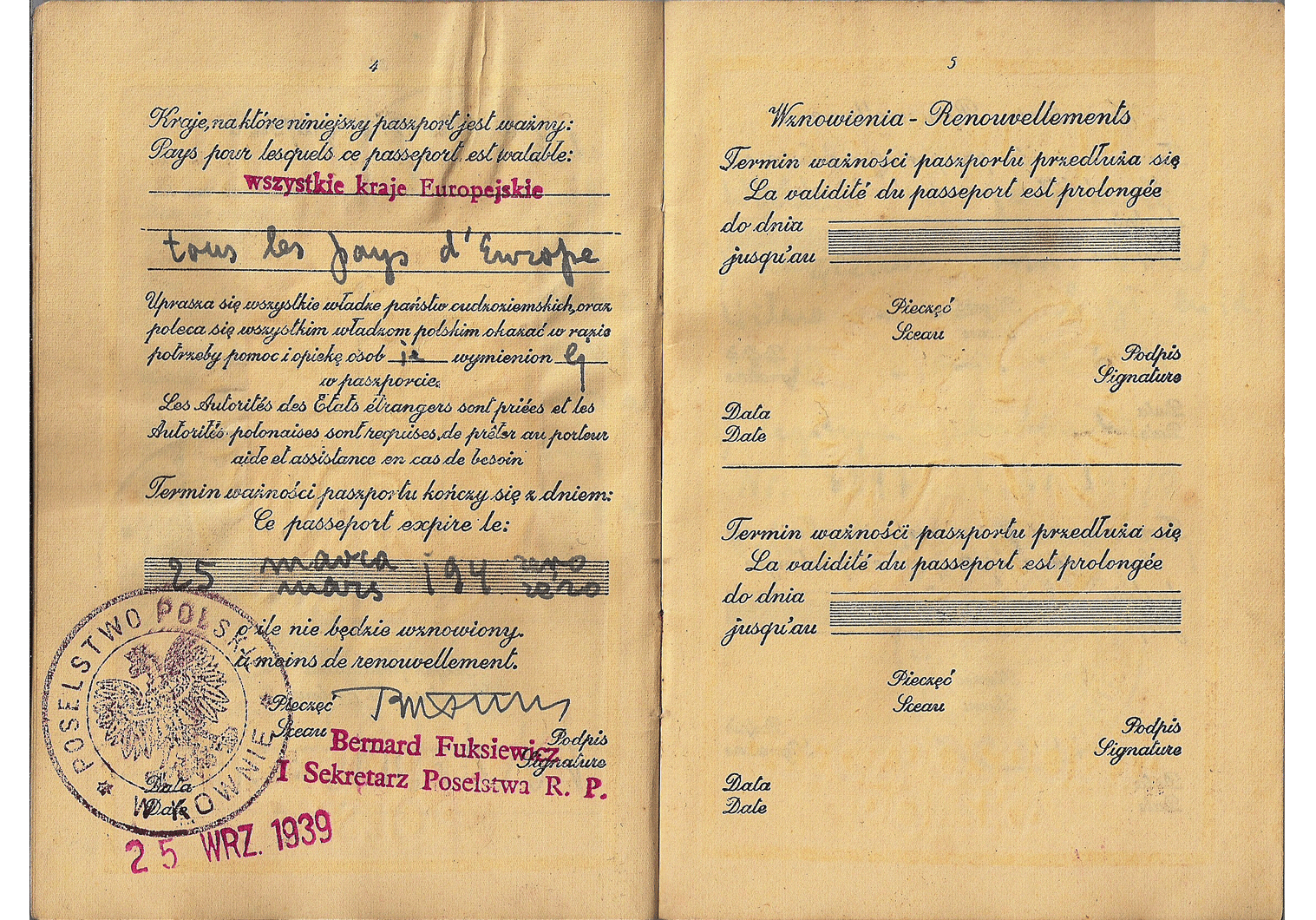

The embassy’s consular section was working around the clock in issuing, at first, regular blue-covered passports to its verified citizens who were in a desperate need of a passport to leave. The staff issued them constantly until mid October, then after protesting of the Soviet handover of Vilnius to Lithuania on October 10th 1939, the diplomatic staff and its legation head evacuated Lithuania on the 14th.

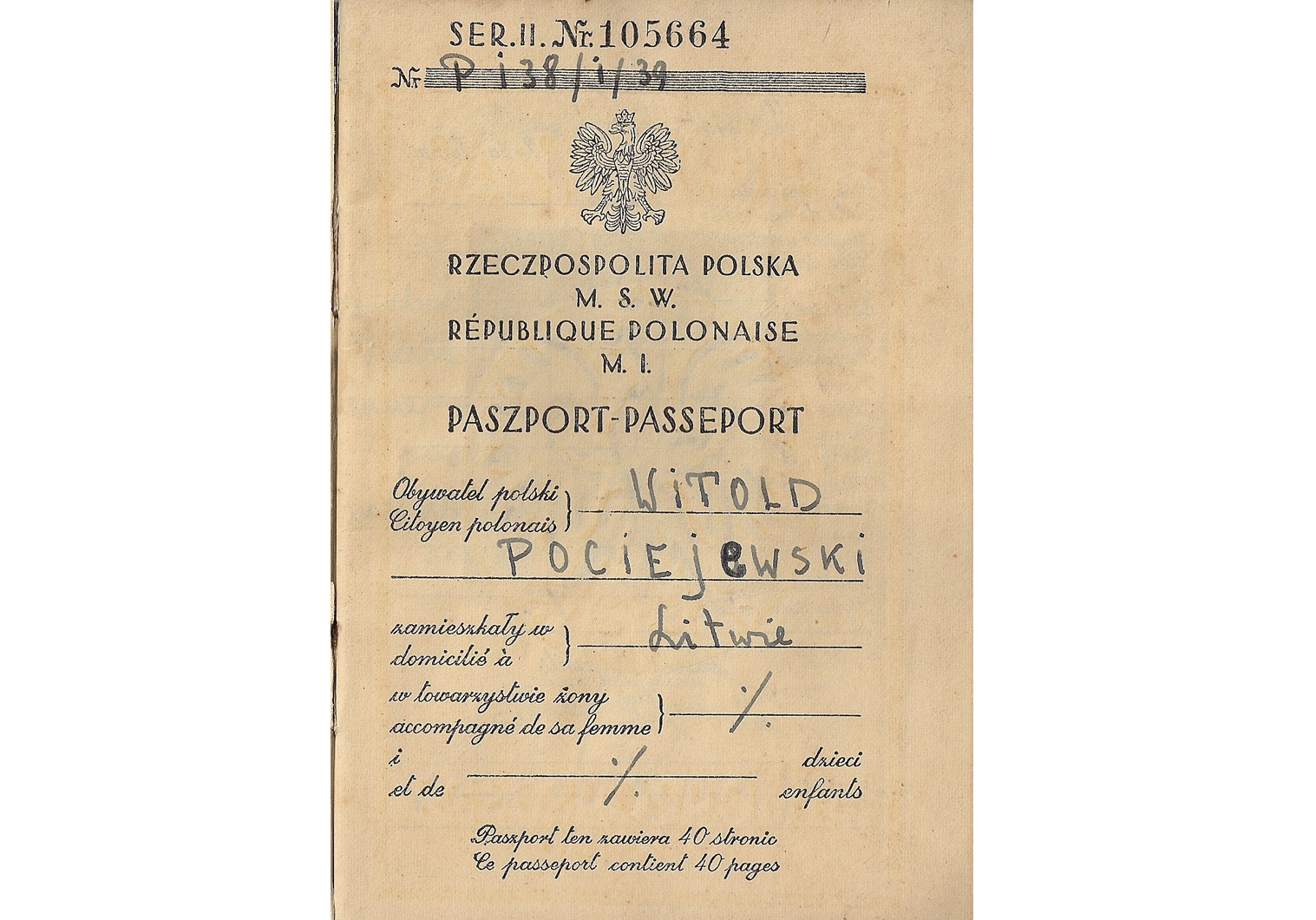

Passport number P 138/1/39 was issued to student Witold Pociejewski, aged 31, by consular staff Bernard Fuksiewicz, First Secretary, on September 25th 1939. He was among the staff that was evacuated about 3 weeks later.

Poland and Lithuania established full diplomatic relations in March of 1938. Its delegation head was senior diplomat Francis Charwat (April 12th 1881, Stanislaw – 1943 Rio de Janeiro), who had a rich history of official postings to Estonia, Finland, Kharkov and more.

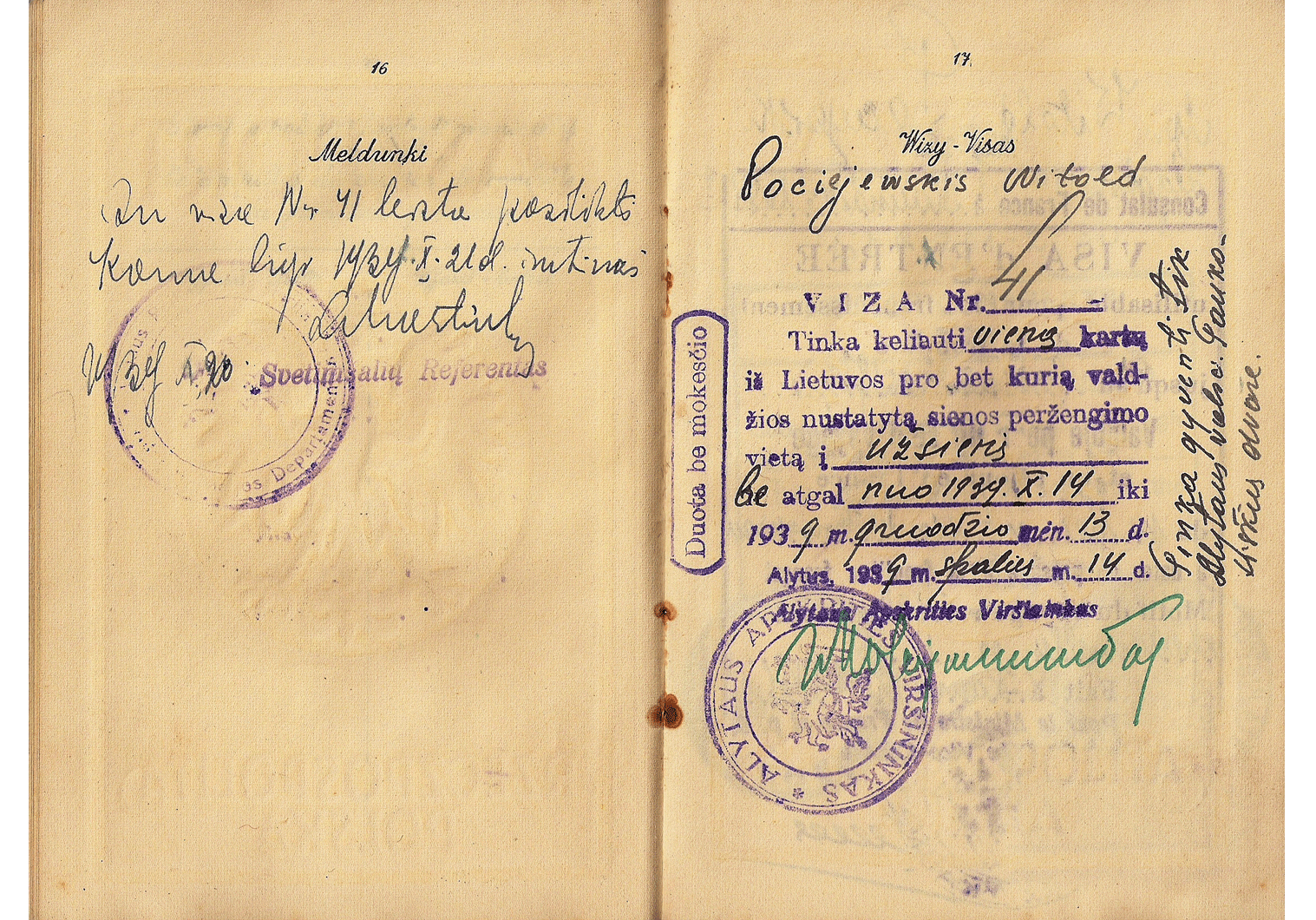

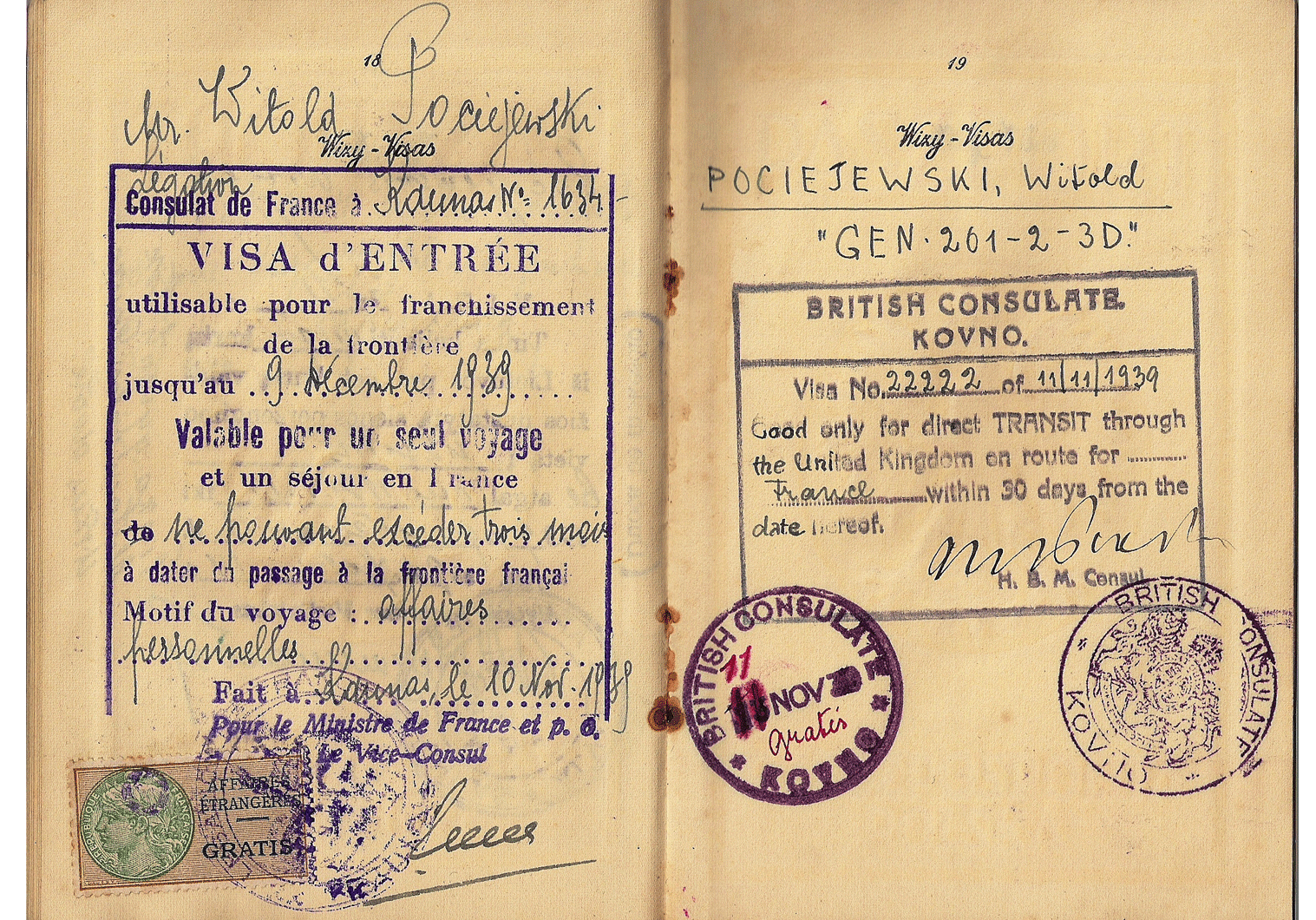

The passport holder even continued his plans of evacuation to the west, by applying for the Lithuanian exit visa on October 14th, valid for 2 months, followed by the French visa from November 10th and then by the British transit visa number 22222 three days later. The latter was issued by diplomat Sir Thomas Preston, who was representing Polish Interests and Charge d’Affaires of that section in the British Legation in Kaunas (he would later be issuing emergency identity documents on behalf of the Polish Government in Exile to some refugees that managed to obtain later on in 1940 the transit visas by famed Japanese consul Chiune Sugihara).

No further entries can be found inside the passport. One then assumes, sadly, that the possibility of not exiting Lithuania prior to the Soviet invasion of 1940 may have been the case. Another possibility is that a temporary travel document could have been issued to him later on, say by the local authorities that enabled him to leave. But this may be wishful thinking. We all hope that escape was the scenario at the end. It is our human nature, when facing our darkest moment, to struggle and cling to every option that can give us life. I believe, as those who are reading these lines as well does, that deep in our hearts we want to learn and find out one day that Witold was lucky to have found refuge far away from the carnage of war.

Thank you for reading “Our Passports”.