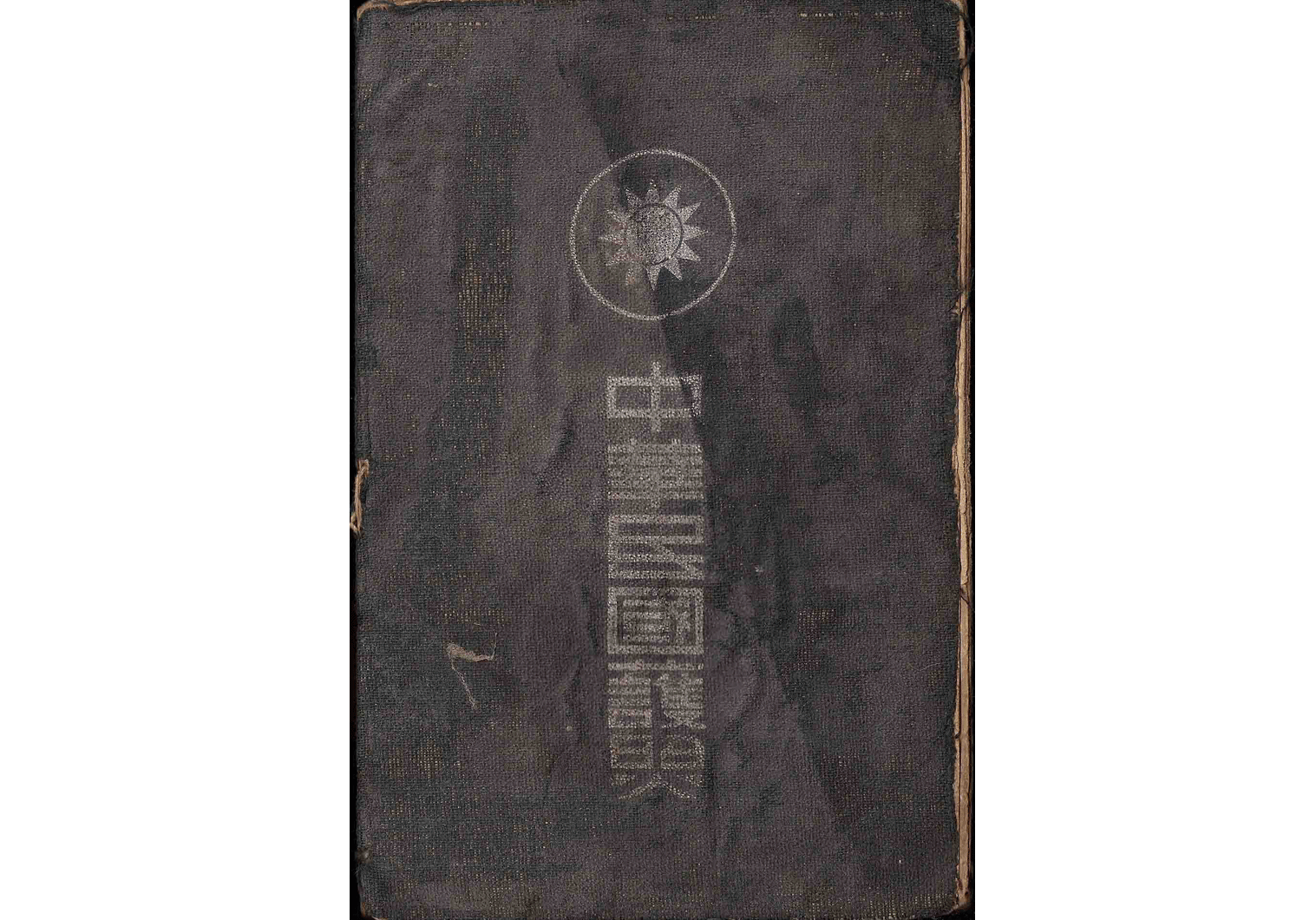

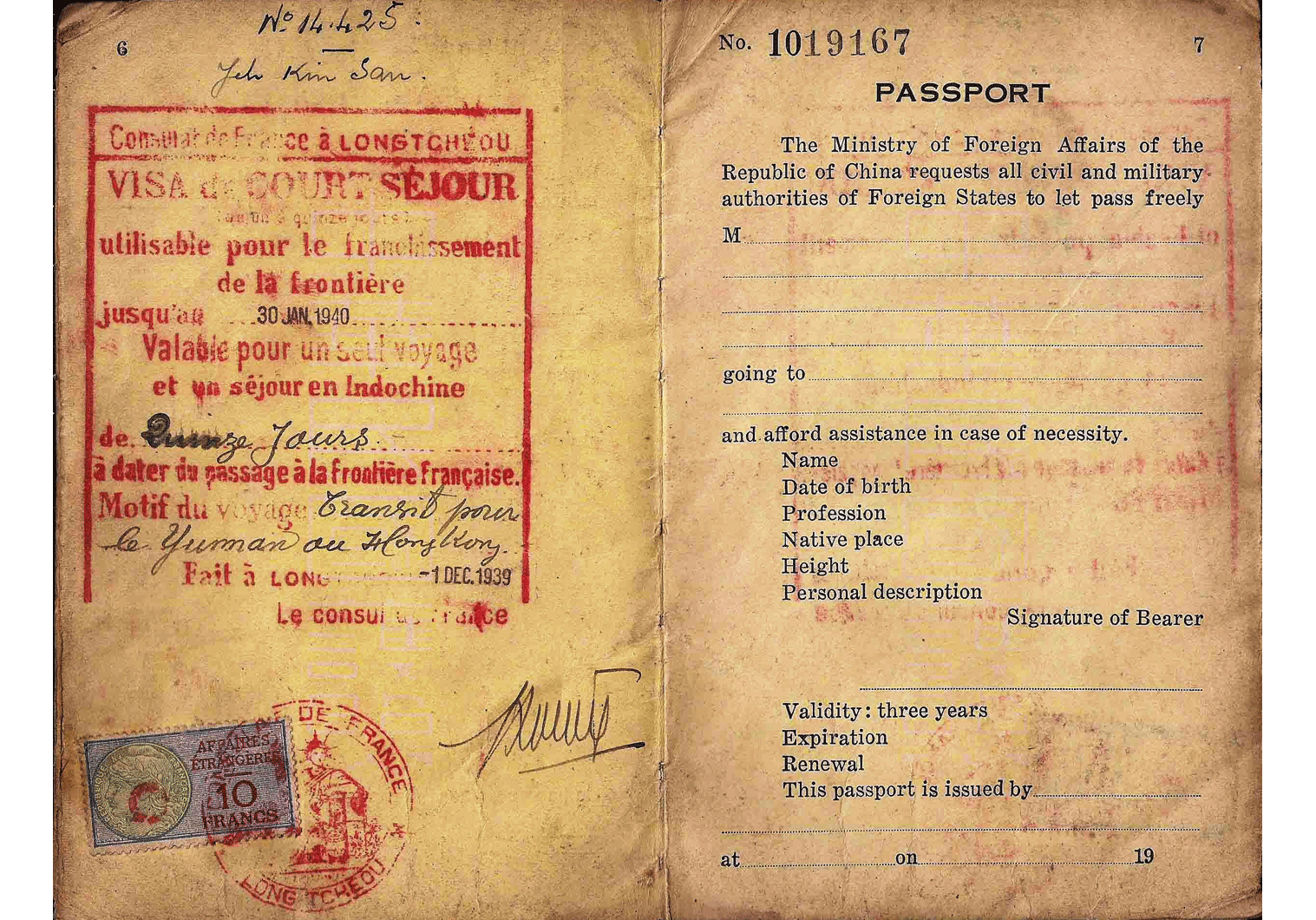

1939 Chinese passport

A public official travelling in the south.

This year was a significant one with regards to the ongoing conflict. Not just in Europe, which signaled the outbreak of war on the continent, but also in Asia, where the war has been raging for years.

During this year several major events and battles took place in the Far East. The Battle of Changsha , September 17th-October 6th 1939, for example, was the Imperial Japanese Army’s attempt (out of four) to take the Chinese city of Changsha (长沙, 湖南), Hunan province. The Japanese were not successful in bringing the city down, a victory that would have enabled them to continue consolidating their territories in southern China. The city was properly defended by General Xue Yue, and this was considered as one of the first battles in China to fall under the time frame of World War Two.

Other important developments of the war during this year were the capture of Nanning (南宁), a border town close to Vietnam (then Indo-China). The battles of Hainan Island and the Gulf of Tonkin also signaled the escalation of the conflict in South East Asia.

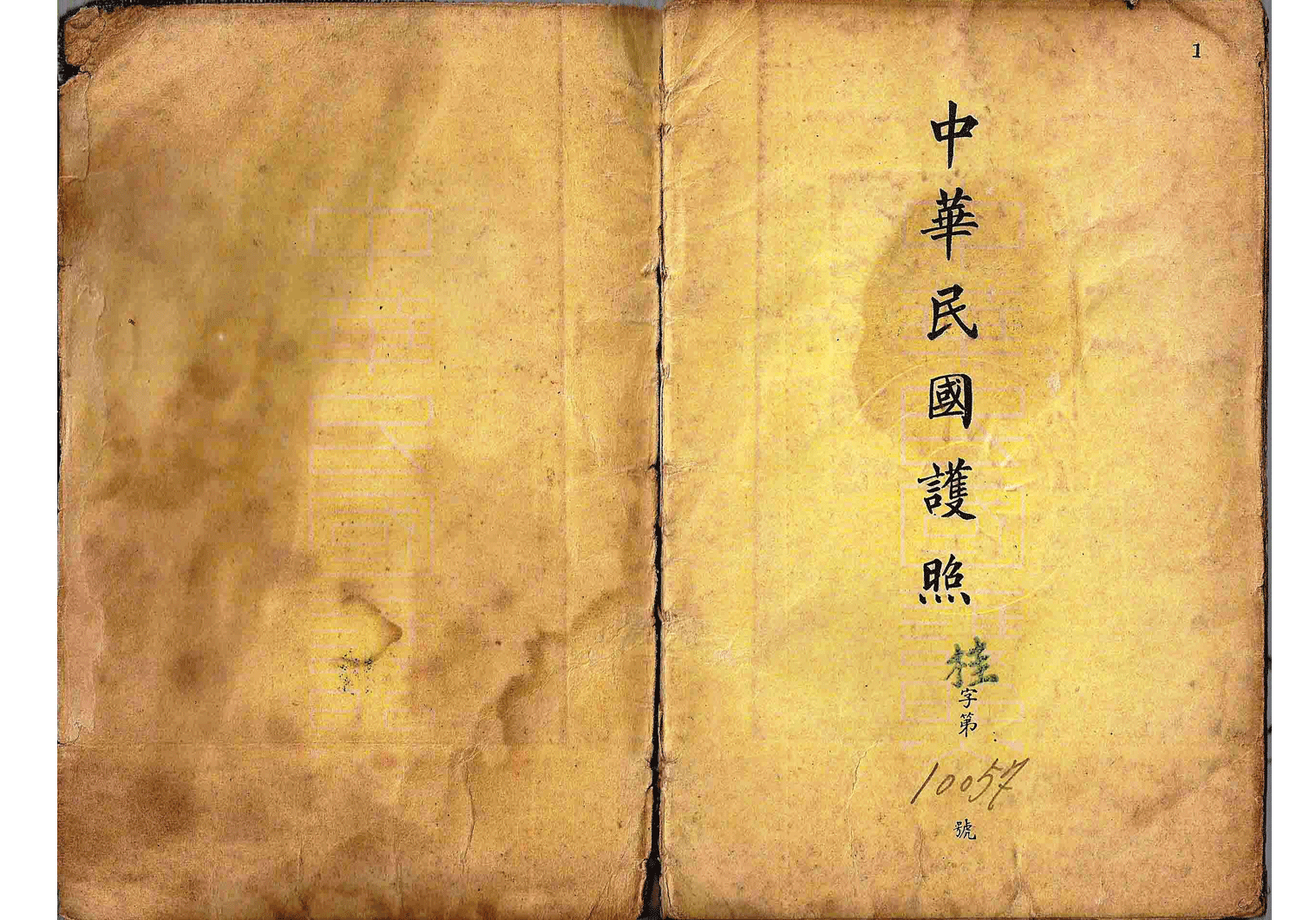

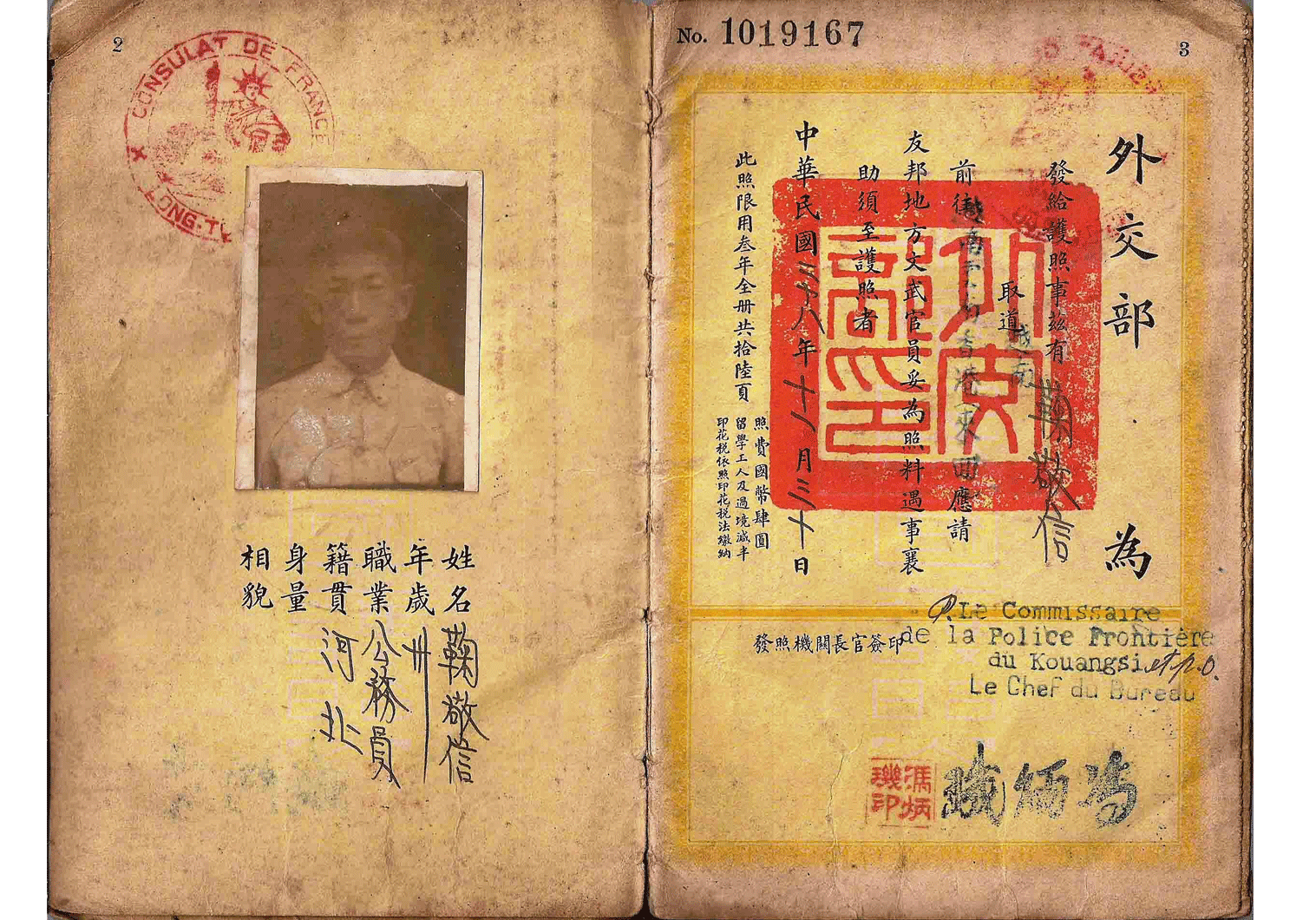

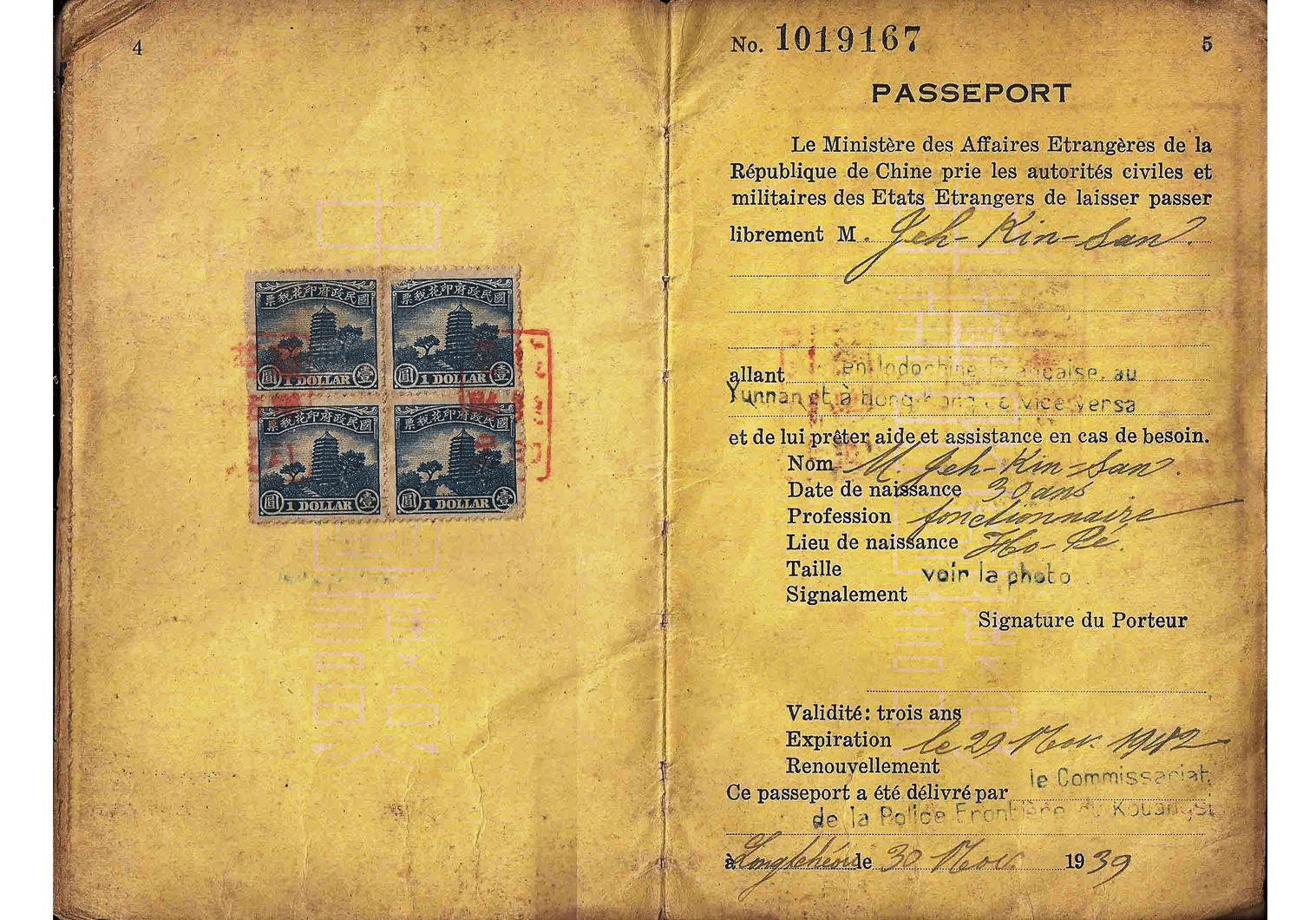

The passport (number 10057) in this article was issued in southern China, at the city of Longzhou (龙州), Guangxi province bordering Vietnam on November 30th to an official/public servant named Ju Jingxin

(鞠敬信).

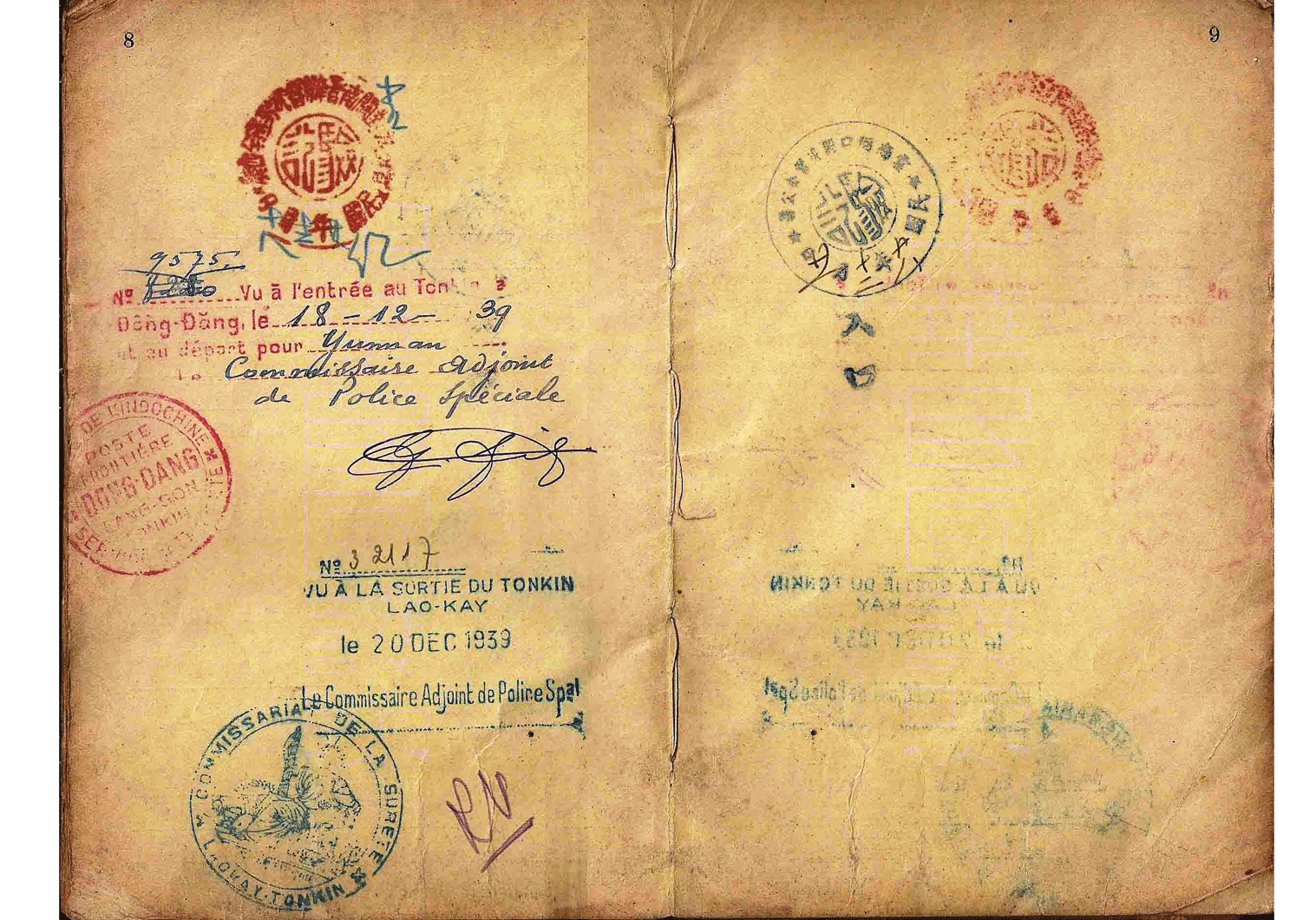

Due to the worsening conditions in the south, the holder had to use a specific “safer” route to reach his final destination – Hong Kong. During times of peace, an individual would have travelled east to reach Canton or via rail to reach the border of Hong Kong. By the time the passport was issued, the only remaining available route was south, and as indicated clearly via applied HAND-STAMP, the route was south to Indo-China and from there to the British colony.

It is very interesting to see how routes could change due to war and conflict.

I have added images of this war-time Chinese official’s passport.

Thank you for reading “Our Passports”.