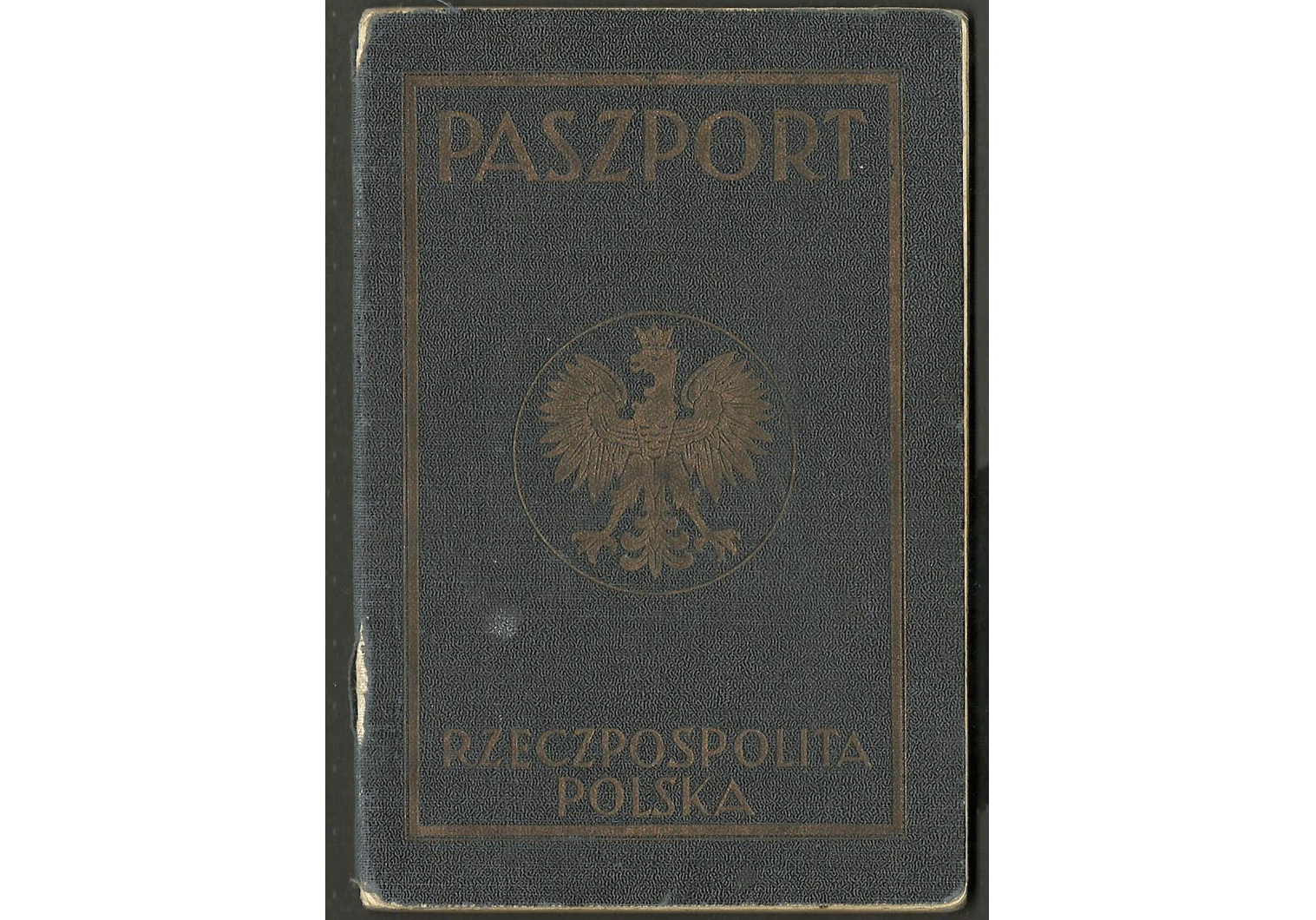

1941 Important Tokyo issued passport

Polish refugee to whom a Sugihara life-saving visa was issued the previous year.

1941 marked a turning point in the escalation of the war in Europe and also at the other side of the world – in Asia. This was the year that can be considered as a major changing point in the war, as it brought changes which would ultimately lead to the downfall and implosion of both Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. But before reaching those epic moments, these two countries would continue to show the world that for them there was no limit yet to the bloodshed, as well as no end to the slaughter and killing of the innocent.

1941 would show the changing of the tides, shifting of sides and eventually also an escalation in the killing. More in particular we think about the German traitorous attack on its former ally, the Soviet Union, the Japanese false negotiations with the US while it prepared for the attack on Pearl Harbor, as well as the invasion of the last remaining safe heavens in the Far East: The Japanese full occupation of Shanghai and the march into Hong Kong and more.

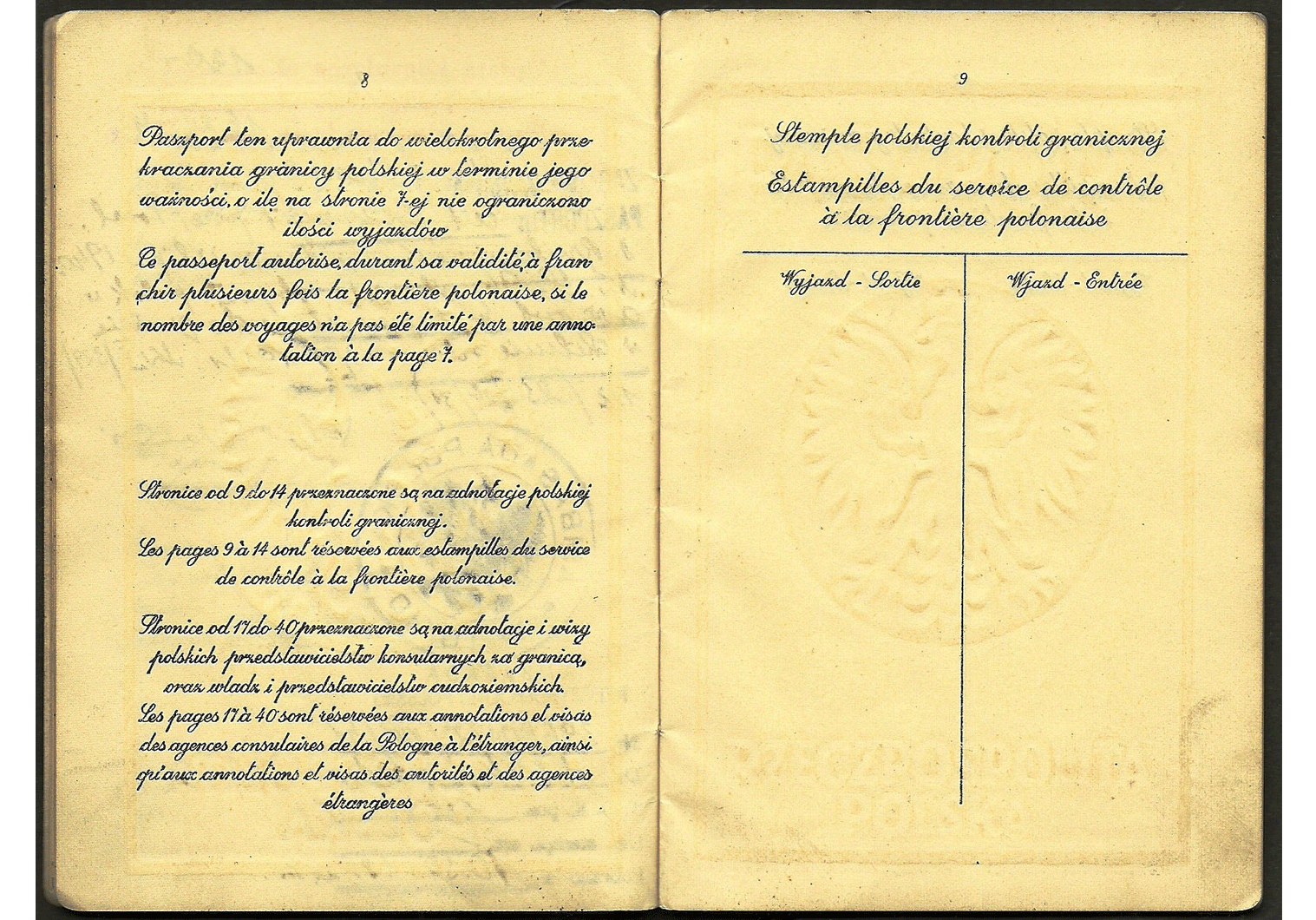

The passport presented in the present article is extra unique because of its holder’s travels up to the point of its issue also from then onwards.

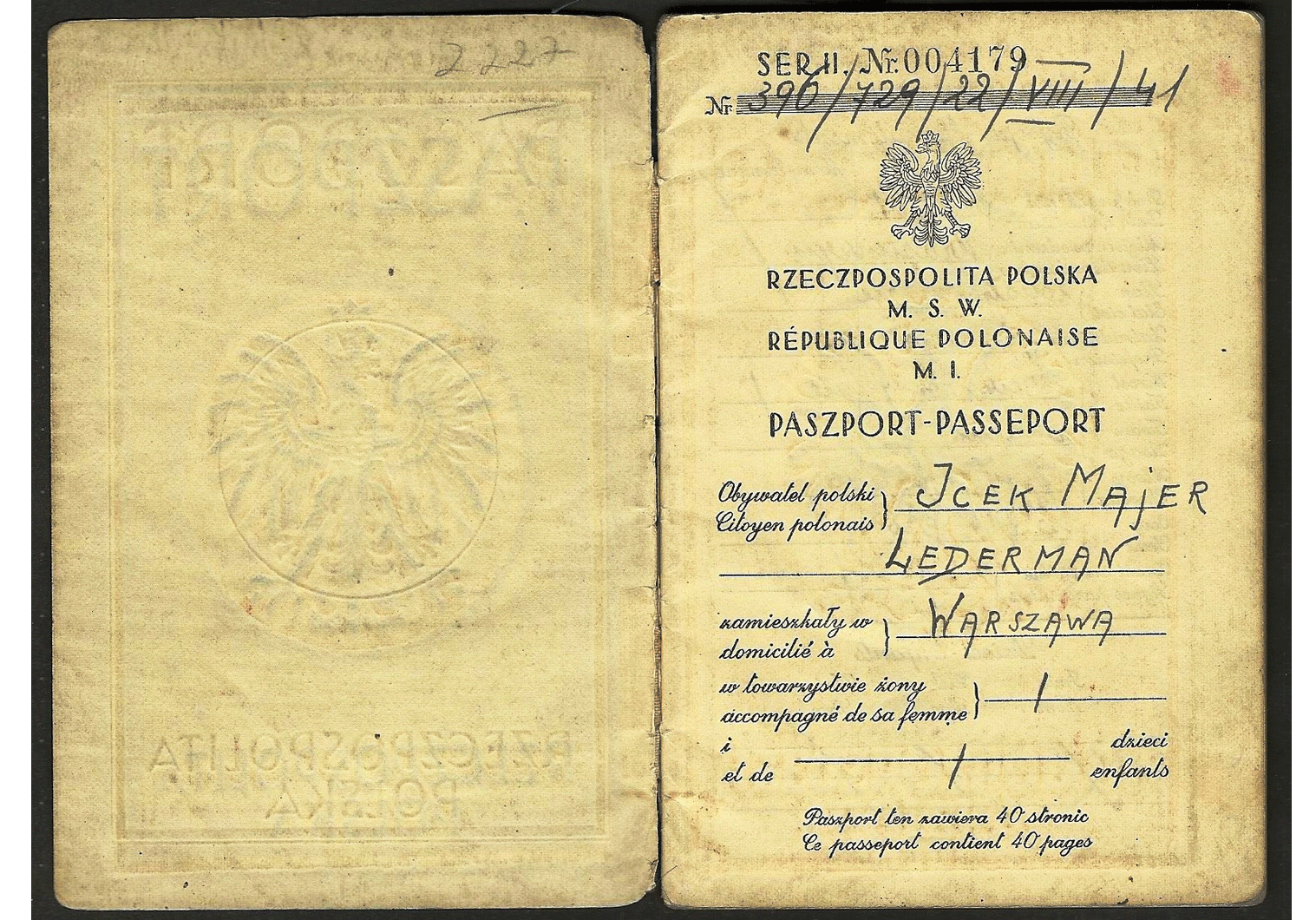

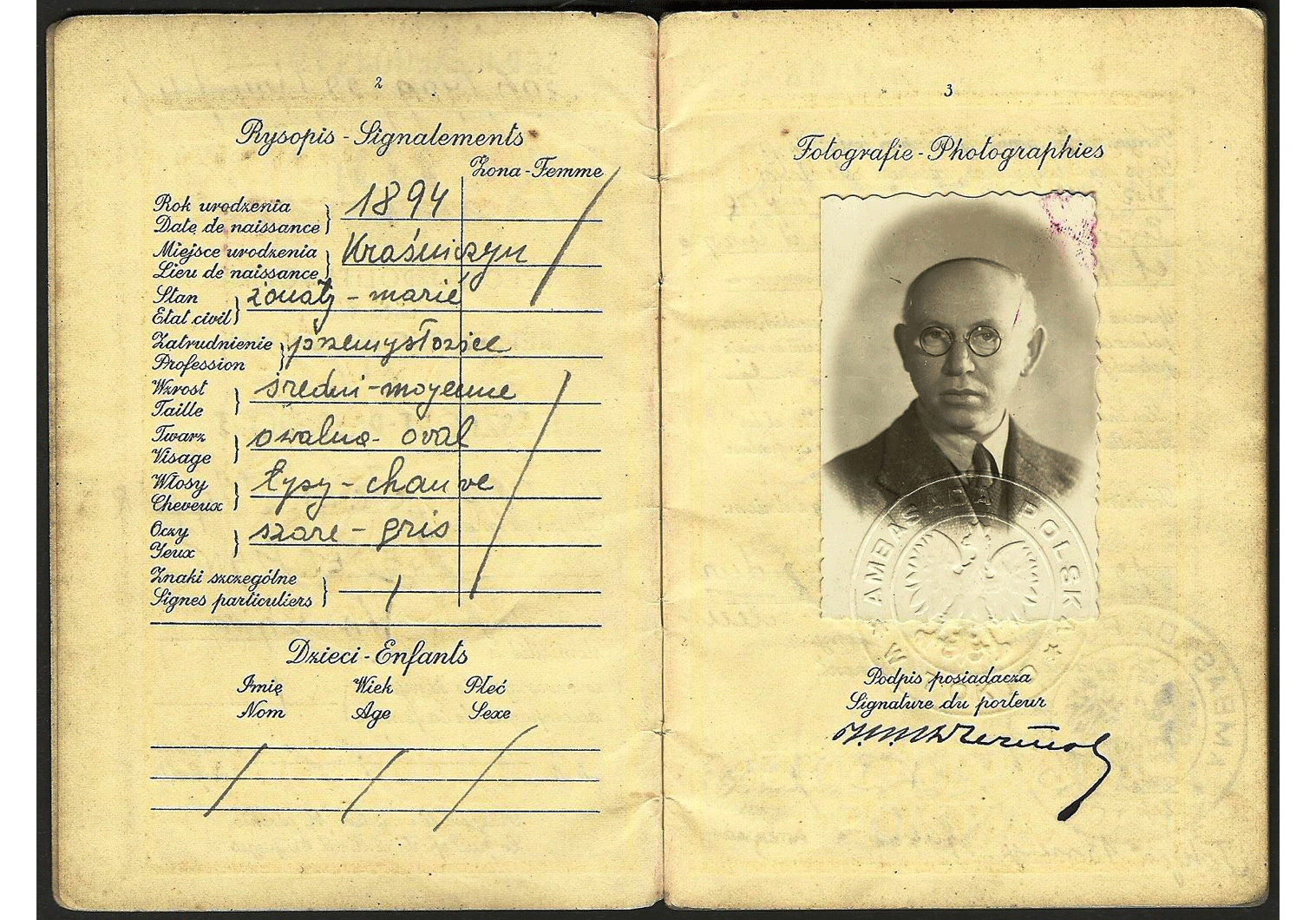

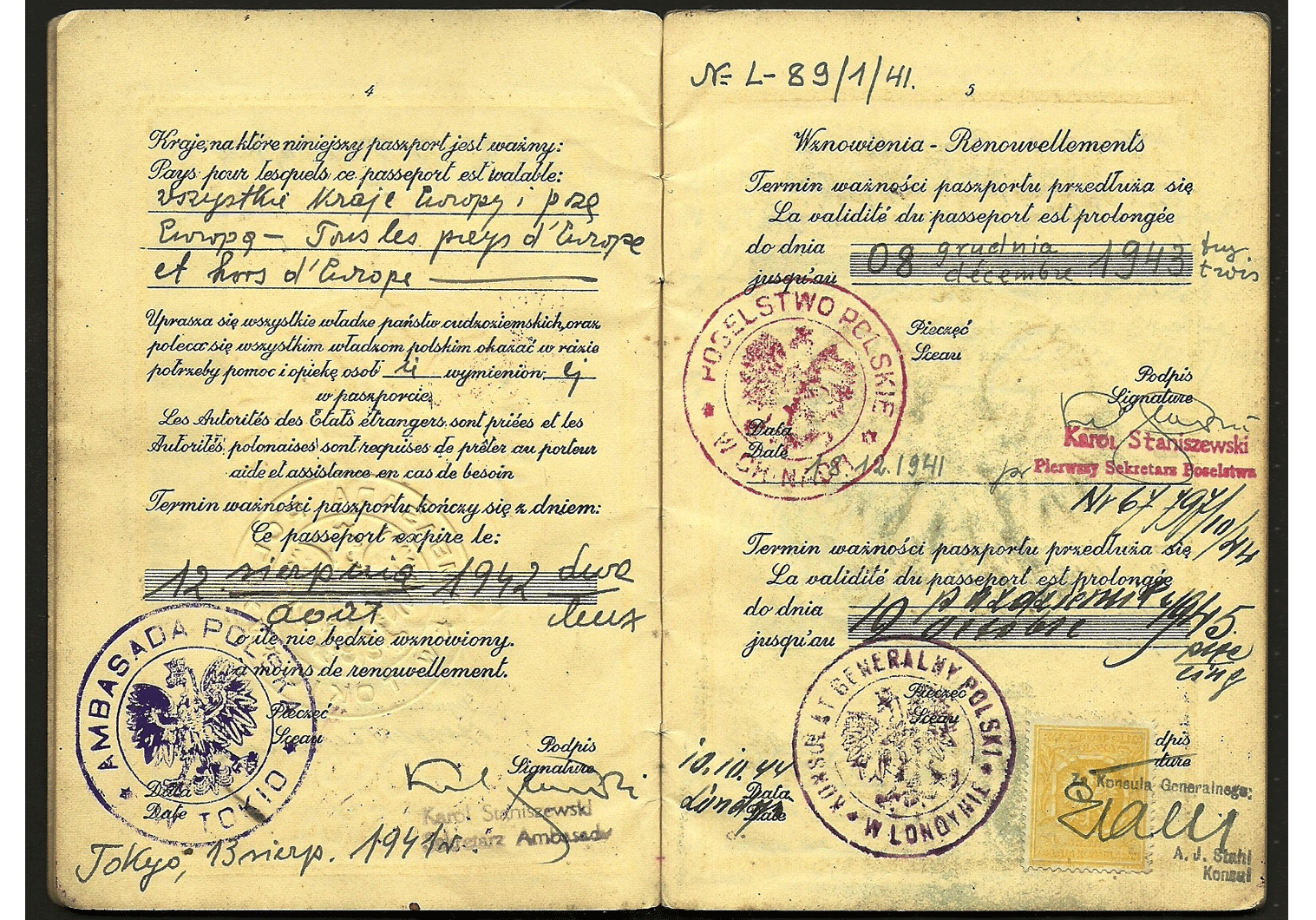

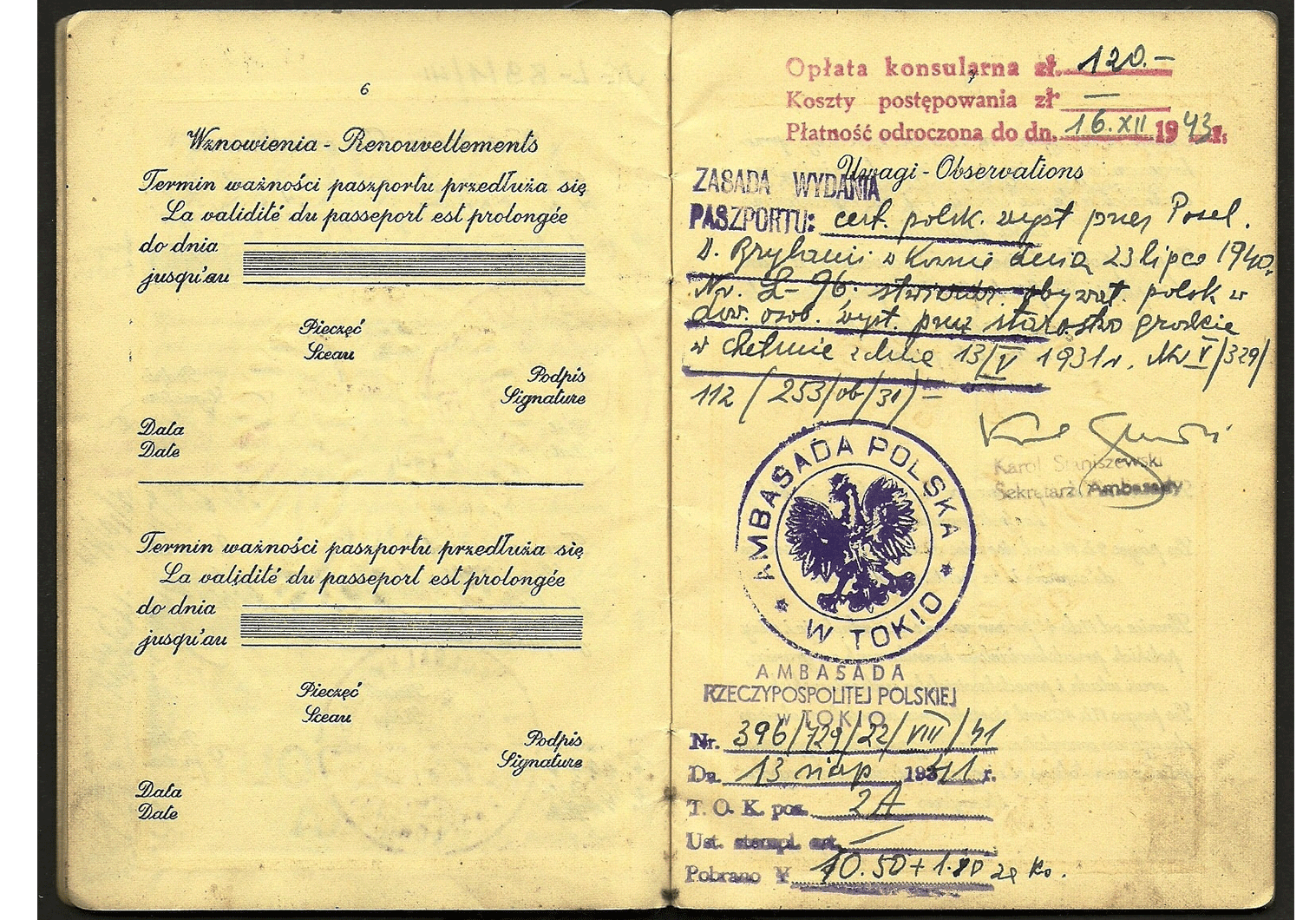

Polish passport number 396/729/22/VIII/41 was issued to Jcek Majer Lederman from Warsaw on August 13th 1941 at the Polish embassy in Tokyo (headed by Tadeusz Romer, the Polish ambassador) by embassy secretary Karol Staniszewski (he would soon became the First Secretary to the Polish legation in Shanghai). The date of issuance is relatively close to the date the embassy was forced to shut down, after October 6th, when the Japanese cut of all ties with the Polish Government in Exile based in London, under German pressure, and also due to the alliance it had in with the Axis. The Polish diplomatic staff would be deported, before Pearl Harbor, to the Chinese port city of Shanghai.

Jcek arrived sometime in 1940 in the Japanese city of Kobe, where most of the Polish Jewish refugees disembarked from boats that had brought them in from the Soviet city of Vladivostok. Hundreds where scuttled to Japan by means of Russian boats in poor condition; all had transited across Siberia and stopped briefly at Moscow after originally departing from Kaunas in occupied Lithuania. Thanks to the brave Japanese consul Chiune Sugihara, over 2,000 Polish Jews and others received a life saving visa. Jcek was among those lucky individuals who received his visa on July 30th 1940, visa number 263. It is at the embassy in Tokyo that he exchanged his travel document bearing that visa for this new passport.

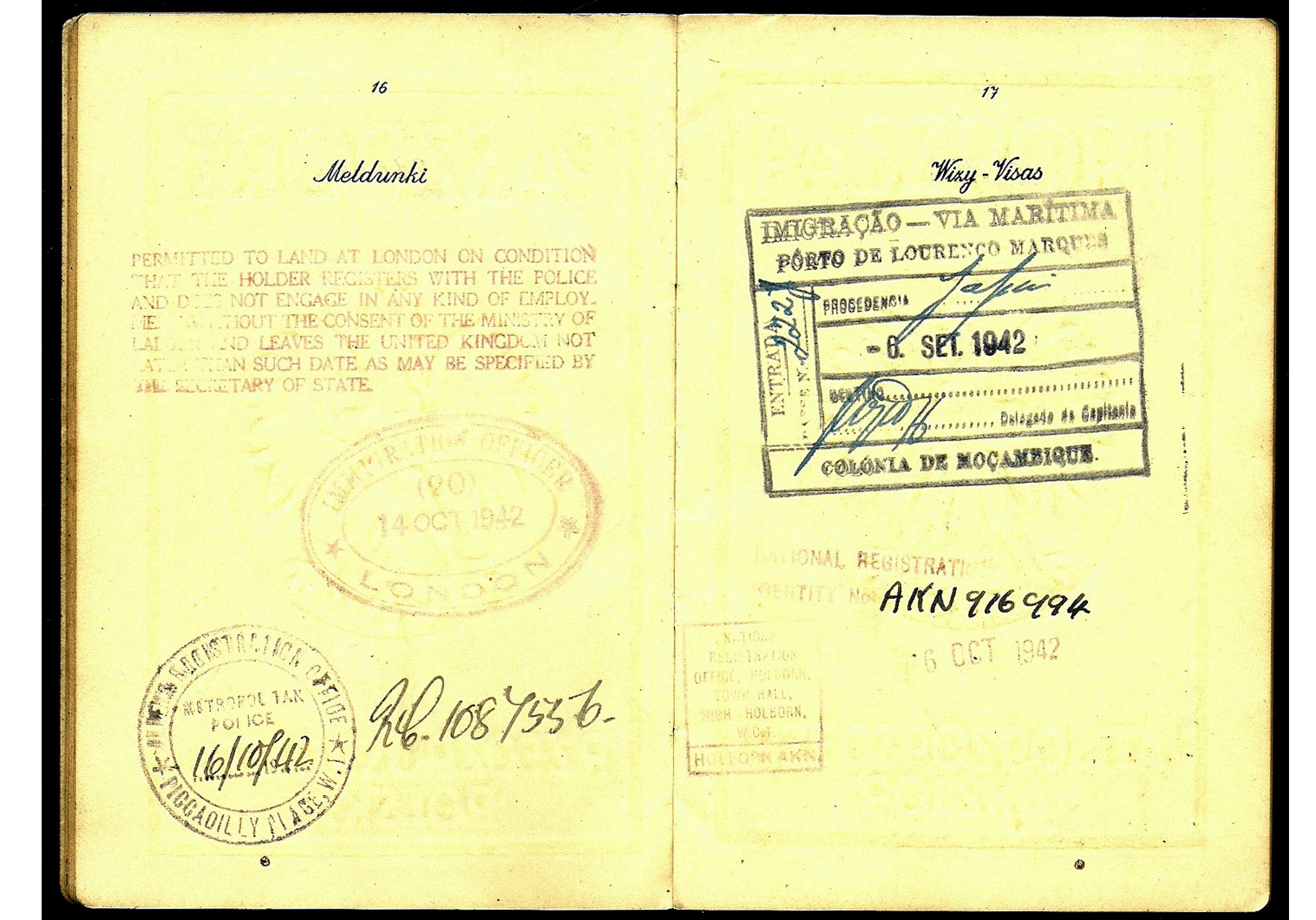

Close to 1,000 refugees with Jcek amongst them and together with the former Polish embassy’s staff, were deported to Shanghai before the Japanese attack on the US Pacific Fleet. Upon arrival in that city, he would have his passport extended at the newly formed Polish legation, again signed by the same diplomat who issued him the passport in Tokyo, Karol Staniszewski (he had also been consul at the Polish consulate at Toulouse, France, 1936).

But when one looks at the next passport extension, lower down, we see it is done at the Polish embassy in London, by Consul Adam Stahl, on October 10th 1944. So, paging through the passport we then find interesting entry markings for Lourenco Marques, from September 6th 1942. After extensive researching, we now can confirm that he was among the civilians, of both the allies and the axis, who were part of an exchange that took place in the east African Portuguese colony of Mozambique. Allied civilians, mainly stateless and neutral, together with diplomats were boarded onto the Japanese liner Asama Maru (other vessels aided in transporting of civilians from the pick-up locations along the way and the transportation of food, via the Red Cross, such as the Tatu Maru & Kamakura Maru). The allies would use the MS Gripsholm. It is rather strange that he would find himself among those being repatriated, because he was no diplomat nor did he hold any prominent position that we know of (though his profession is indicated as “industrialist”); yet, he was possibly connected in some way to the Polish elite or diplomatic circles, we can presume, which could explain his placement into the exchange list.

Jcek was a very lucky man. Three times he managed to cheat death during the war:

First when fleeing to Lithuania in 1939; a second time when obtaining the life-saving Sugihara visa on July 30th 1940 and a third time when he got on board the vessels that took him to safety, away from Shanghai, in 1942.

For a more complete understanding of this repatriation and war-time life under Japanese occupation in China, please read Greg Leck’s book “Captives of Empire“. It is a wonderful source on civilian internment life under the Empire, fully illustrated and a treasure for WW2 enthusiasts and collectors as well!

I would like to thank Henk Slabbinck for his contribution to this article.

He has been a source of vital information and also a dear collector.

I have added images of this important WW2 Polish passport.

Thank you for reading “Our Passports”.

Maria S. C.

My grandfather is Karol

Staniszweski. Amazing to read details about the vague stories i’ve heard all my life. How did you get all these details? Fascinating

Arlette Liwer

It was not only Sugihara but also thanks to the brave efforts of the Dutch Consul Jan Zwartendijk who issued fake destination visas to Curaçao. Most of the transit visas to Japan would not have been possible without the destination visas to Curaçao. My grandparents and aunt received a Polish passport in Tokyo. In fact, my aunt worked for a short while in the embassy. Thank you for this article which I found helpful.