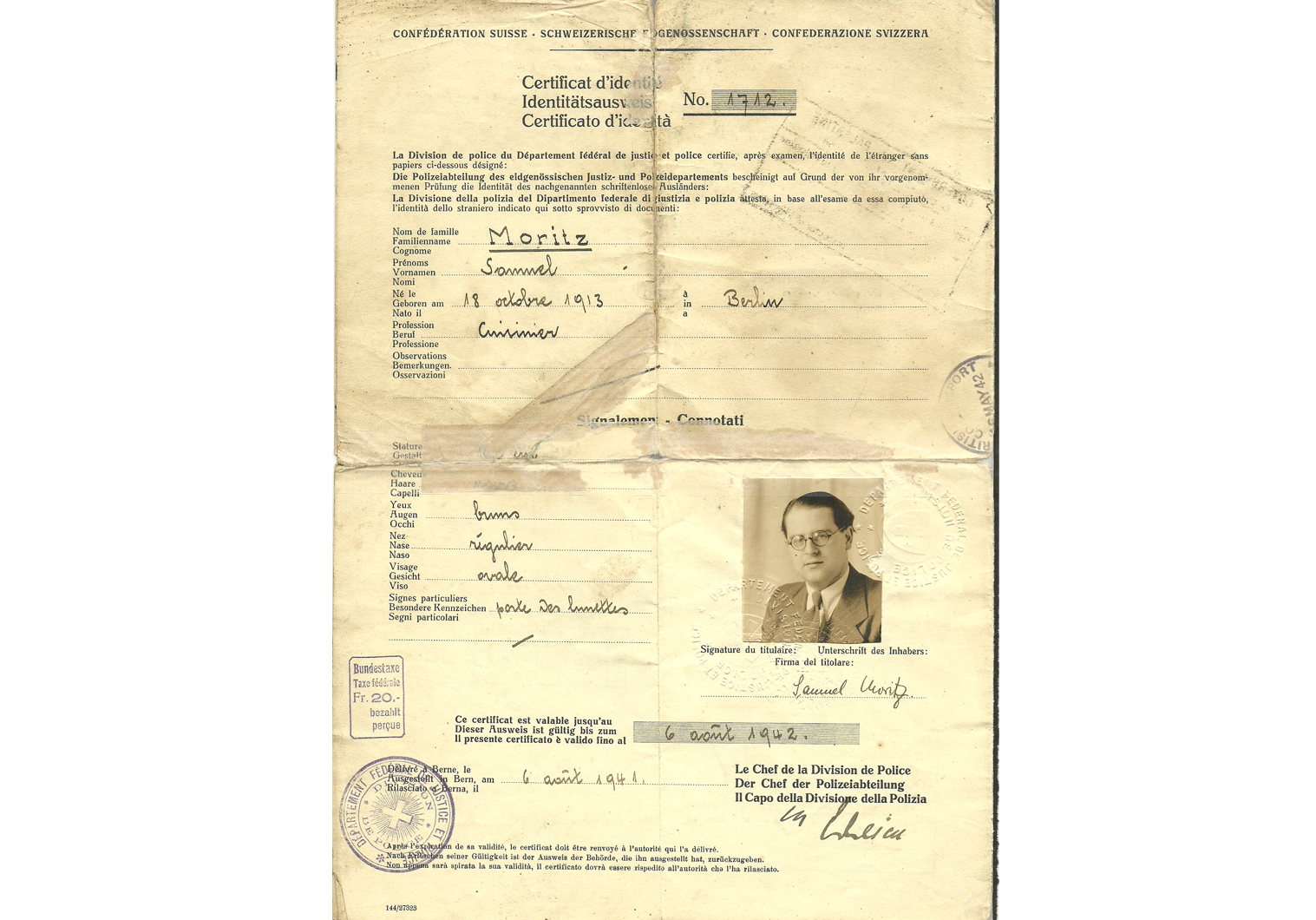

1941 Swiss Identity Document

Issued to the Stateless and refugees for traveling abroad.

World War Two ushered many changes to the old world; changes that had a profound effect on us all and that can be felt even today.

The technology that was discovered and used during the war had a huge effect on us all, on house appliances, aviation and weaponry that would be produced later on during the 20th Century. Additional changes can be attributed to the production and usage of documents, be it ID’s and passports, were made during them long 6 years of the war. We can say that during the times of crisis some of the best, and sadly also the worst, of discoveries are made. The type of paper, printing and security measures, for example, altered the way we look and handle ID’s and travel documents today. Such developments may not have occurred at all had the world not been plunged into years of conflict that resulted in the destruction of the old order that existed prior to 1939 and most significantly to the horrendous loss of life.

The rise of Nazi Germany to power in 1933 had many changes to the way countries viewed their borders, entry procedures and document issuing.

Before the outbreak of war, Europe was plagued with refugees – due to the Great War, the Bolshevik Revolution and last, due to the events mentioned above in Germany. People, either fleeing citizens or stateless people, were frantically trying to find refuge abroad, be it overseas in the United Sates, South America or even as far as the Far East. And some were even trying, be it even temporarily, in the continent itself, and this this case, in little small Switzerland.

The Swiss went through two main pre-war refuge “stages”: 1933 following the rise of Adolf Hitler to power and also in 1938, after the Anschluss and then followed by Kristallnacht several months later (On March 31st 1933 a new federal decree set the regulations regarding the treatment of different type of German refugees: those to be deemed as Political Refugees and those as Emigrants. This had dire consequences when it came to German Jews because the authorities did not deem Jews under persecution in Nazi Germany as political refugees, who could be entitled to permanent residence status in the country, thus being termed as emigrants, and were ONLY permitted, in some cases, for temporary stay in the country and must continue with their travel arrangements abroad, and in this way being termed as transmigrates).

During the first wave of refugees, 1933, shortly after the changing of power in Germany that year, close to 10,000 refugees entered Switzerland with over seven thousand of them arriving at the Basel train station alone. Majority of them leaving the country the same year and also many loosing their citizenship as well, or passports not being issued by the consulates abroad, fowling new German regulations or policies, just intensified their plight and their status in the small country. These events led, as mentioned above, to stricter policies towards foreigners being placed (the definition that Jews escaping racial persecution where not allegeable to be classified as political refugees thus being entitled to asylum changed in mid 1944, when the authorities finally accepted the fact that Jews were in physical danger).

The second wave that followed in 1938, following the Anschluß in March and then by the violent atrocities committed in what would be termed as the “Night of broken glass”, where the Jewish population, in an instant, lost all their rights and privileges following the German takeover of the country, with scenes of Jews on their knees cleaning the streets with their fellow countrymen cheering with joy at the spectacle.

With the situation of the refugees worsening by the day, and the borders being overwhelmed by Jews fleeing neighboring Germany, the authorities were looking for ways to curve and event contain the flow, thus consultations began between the two countries. The Swiss pressured their neighbor to find a way to assist in identifying who was a non-Jew and who was Arian: no visa was required between the two and the threat of implementing visas was enough to convince Germany to adopt to marking the Jewish passports with an identification mark: a large red J (at first Berlin was reluctant in doing so because this would hamper her efforts in forcing the Jews to leave and immigrate, marking such passports would make it easier for other countries to identify who was Jewish and prevent their entry, by then, it became more and more difficult for Jews to find countries that would accept them). The joint protocol regarding this matter was reached on September 29th 1938, and the Federal Government approved it on October 4th (the earliest J stamped passport that I have dates from October 11th, a week later). In addition, German Jews had to start to apply for visas when wishing to enter the country, were as their Arian countrymen did not: Interesting to note that the reason for having the red J stamped inside the passport was kept secret for many years, only to be made public by the Allies translation of German material in 1953.

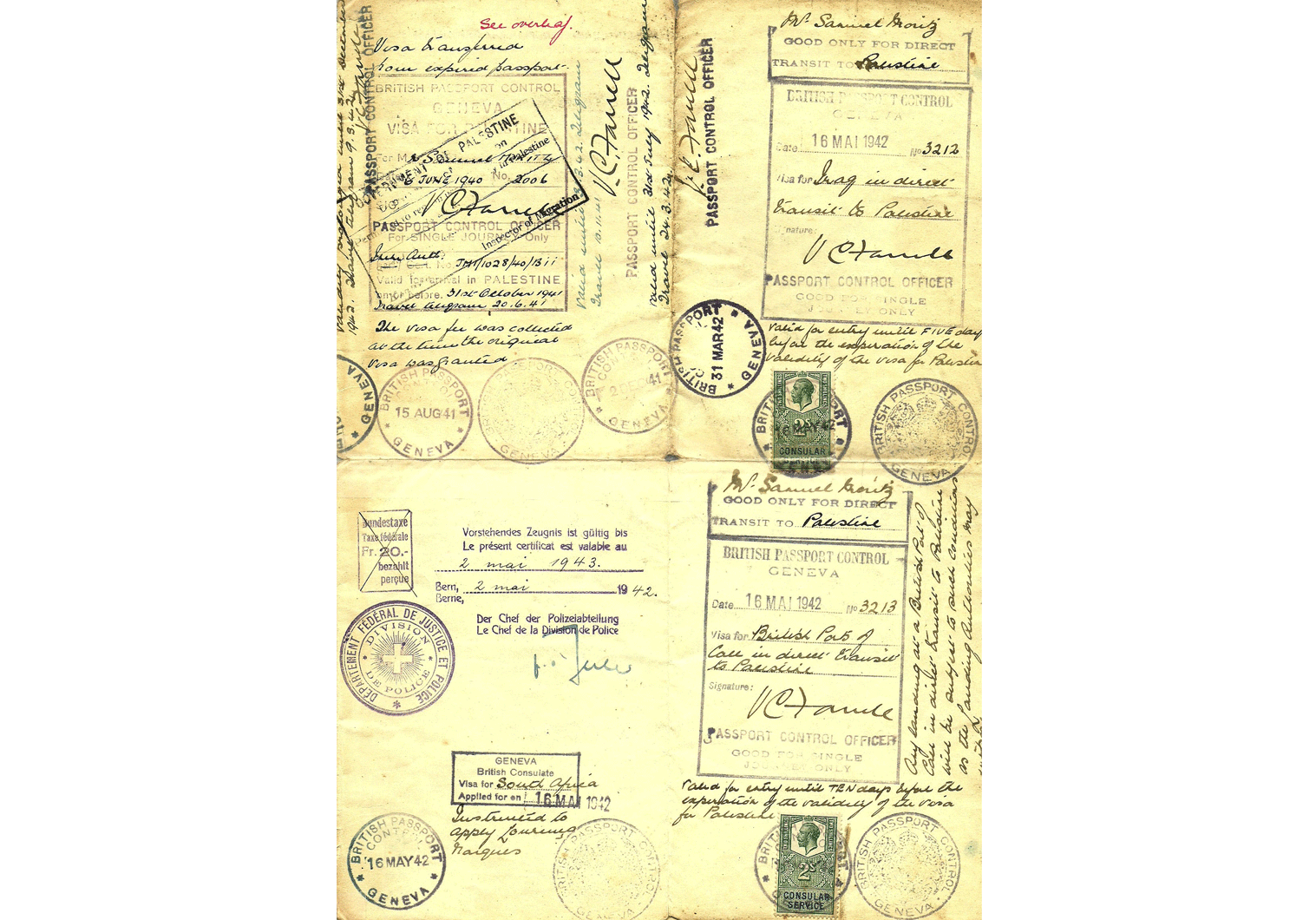

The document in this article is an example of a lucky individual who received entry to Switzerland, from Germany and most likely using a J stamped passport (we can assume this to be the case because of the British visa that was issued inside the travel document at Geneva on August 15th 1941, were the immigration authority sent from Jerusalem, as appearing on the long serial number at the bottom (JMI/1028/40/Bii), indicates the year was most likely 1940, and at this time all German passports issued to Jews wanting to leave the country were applied with the large red J.

Swiss Identity Certificate number 1712 was issued to Samuel Moritz aged 28 from Berlin, occupation being a chef or cook. The document was issued on August 6th 1941 at Bern.

Apparently, Samuel had a British issued visa inside his previously issued German passport which may have expired, and was unable to renew it once in neutral neighboring Switzerland, thus prompting him to apply for the Identity Certificate here. The British consular section indicated at the top of the visa that “The visa transferred from expired passport” and valid until July 31st 1942.

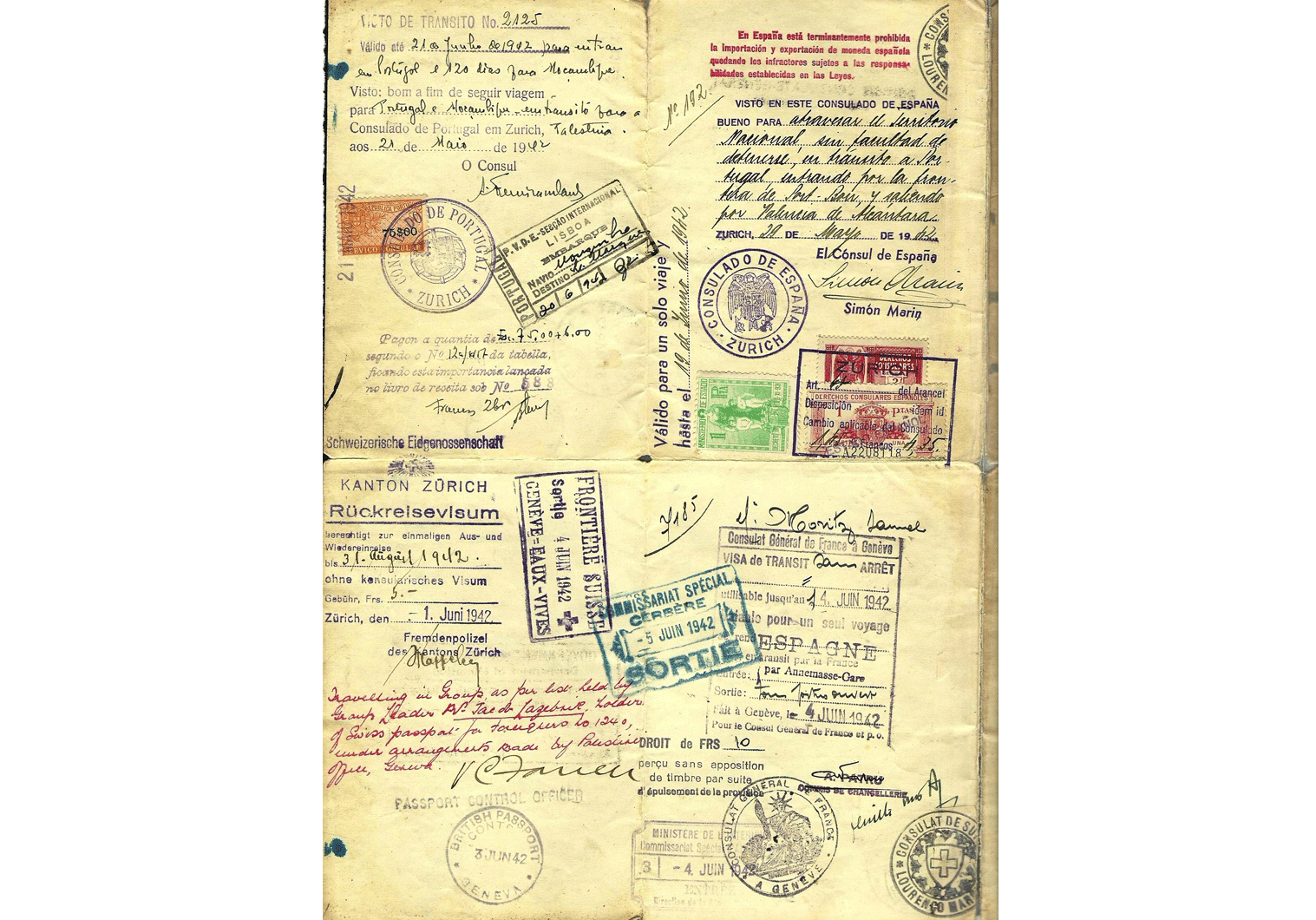

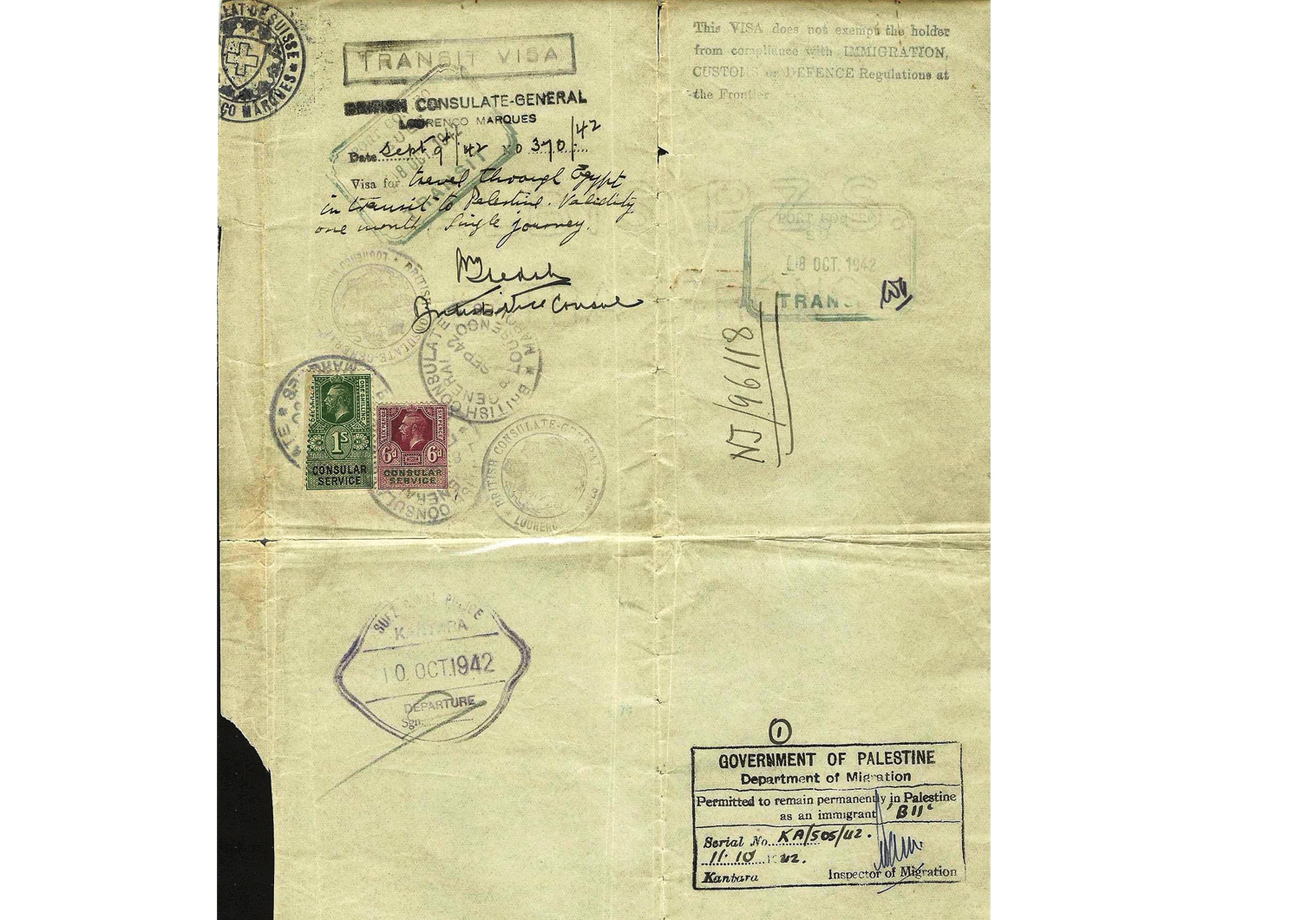

Samuel was not able to leave the country until the following year, so his visa for British Palestine was amended and extended again at the consular section by the PCO in Geneva on May 16th 1942, with an additional application done for a transit visa for South Africa (the Swiss police authorities extended the document to May 2nd 1943 the same year).

During the last days of May Samuel also applied for transit visas from the Portuguese and Spanish consular sections as well. He needed to board a boat from neutral Portugal in order to sail to South Africa; there was no sailing possible through the Mediterranean due to the hostile waters being controlled by the Axis German and Italian navies (the Spanish visa was issued by diplomat Simón Marín García (1899-1984)). A French transit visa, through Vichy France territory was issued on June 4th as well.

An important note that needs to be mentioned here regarding this document is the special red annotation added by the PCO on June 3rd “Travelling in group as per list held by group leader Jacob Lazebnik, holder of Swiss passport for foreigners no. 1240, under arrangements made by Palestine Office, Geneva“. This is a special addition to this rare travel document, an indication that a group of stateless and refugees where trying desperately to leave war torn Europe via neutral countries.

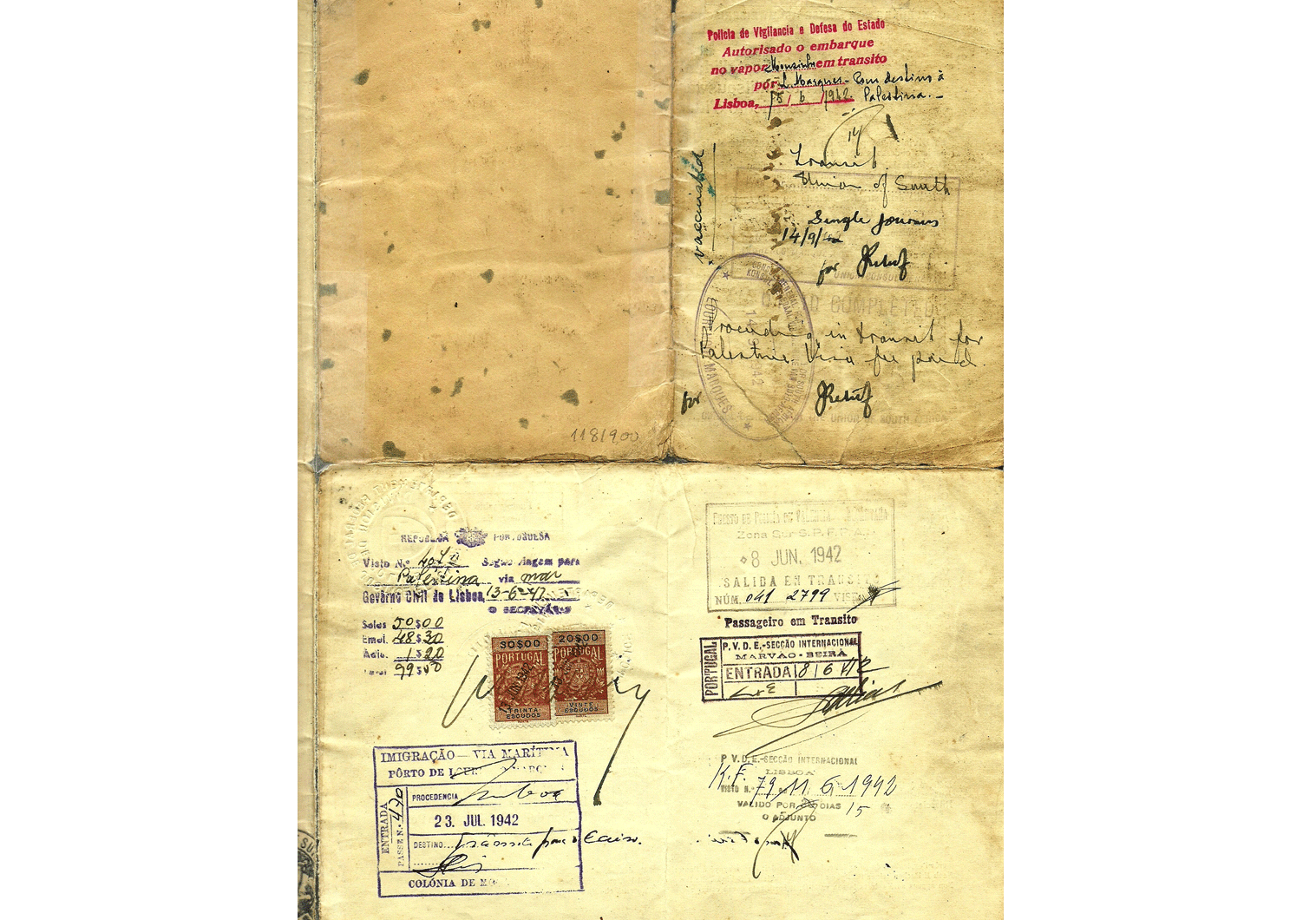

The group left Switzerland in June 4th 1942 and entering Vichy France at Annemasse-Gare on the same day and exiting via the border crossing of Cerbere on the 5th. Exiting Spain into Portugal was done 3 days later at Marvão-Beirã train station. On June 20th he boarded a boat that will take him around the Cape of Good Hope and there he will temporarily disembark at Lorenzo Marques, the Portuguese colony. There he would revalidate his British transit visa, good for transiting through Egypt for one month, by vice consul Claude K. Ledger.

Samuel and the group would cross the joint Egyptian-Mandate border crossing of Kantara on October 10th (arriving 2 days earlier) with the official arrival marked for the next day.

When his ordeal started in 1940, he most likely did not expect the route to be taken to last more than 2 years. After a very long period of time transiting through many countries, his journey came to an end, a good one we hope, in the British Palestine.

I have added images of this war-time related document.

Thank you for reading “Our Passports”.